It is estimated that in 2015 there will be 850,000 people living with dementia.

Having decided at the beginning of last year that I would to any conferences on dementia, I found myself attending the Alzheimer’s Show in London Olympia and Manchester; the Alzheimer’s Association conference in Copenhagen of a book signing, Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow (which was themed on autonomy and dignity; and human rights), Alzheimer’s BRACE in Bristol on the future, Dementia Action Alliance Annual conference 2015 and the Dementia Action Alliance Carers’ Call to Action 2015. So, in other words, I utterly failed.

I will be a guest on a panel in the plenary discussion for “Leading Change in Dementia Diagnosis and Support: Actions to Inform Future National Strategy” to be held at the King’s Fund on Tuesday 24th February 2015.

Full details of this one-day conference are here.

The hashtag for this event is

#kfdementia

.

Details of our discussion are as follows.

| 3.40pm |

Panel discussion: shaping a new national strategyTake this opportunity to put your comments and questions to our expert panel about the key issues that need to be addressed when designing and delivering the next national strategy. George McNamara, Head of Policy and Public Affairs, Alzheimer’s Society in conversation with:

- James Cross, Area Manager and National Lead for Dementia and Mental Health, Skills for Care

- Rachel Niblock, Carer’s Call to Action Coordinator, Dementia Action Alliance (invited)

- Gary Rycroft, Solicitor and Partner, Joseph A. Jones & Co Solicitors and Member, The Law Society Wills & Equity Committee

- Beth Britton, Expert by Experience

Beth’s father had vascular dementia for approximately the last 19 years of his life. She is now one of the U.K.’s leading campaigners on dementia and a Consultant, Writer and Blogger

- Dr Shibley Rahman, Academic in Policy of Living Well with Dementia

- Chris Roberts, Expert by Experience

Chris is in his early 50s and is living with young onset vascular dementia. Chris is a dementia friend champion and writes a regular blog to raise awareness. |

The following are very familiar “mutual tweeps” to me, and I wish them all well for their involvement on the day too.

- Professor Alistair Burns (@ABurns1907), National Clinical Director for Dementia

NHS England and Professor of Old Age Psychiatry, University of Manchester

- Jean Tottie (@Jean_Tottie), Chair of the Life Story Network and Former Carer

- Jeremy Hughes (@JeremyHughesAlz), Chief Executive, Alzheimer’s Society

- Dr Martin Brunet (@DocMartin68), GP, Programme Director, Guildford GP Training Scheme

- Rachel Thompson (@raheli01), Admiral Nurses Lead, Dementia UK (invited)

- George McNamara (@George_McNamara), Head of Policy and Public Affairs, Alzheimer’s Society

- Richard Humphries (@RichardatKF), Assistant Director of Policy, The King’s Fund

- Beth Britton (@BethyB1886), Expert by Experience

Beth’s father had vascular dementia for approximately the last 19 years of his life. She is now one of the U.K.’s leading campaigners on dementia and a Consultant, Writer and Blogger

- Gary Rycroft (@garyrycroft), Solicitor and Partner, Joseph A. Jones & Co Solicitors and Member, The Law Society Wills & Equity Committee

- Chris Roberts (@mason4233), Expert by Experience

- Tony Jameson Allen (@SportsMemNet), Director, Sporting Memories Network, and Winner of the Best National Initiative Award at Alzheimer’s Society National Dementia Friendly Awards 2014

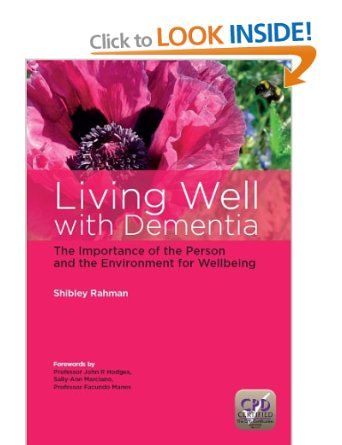

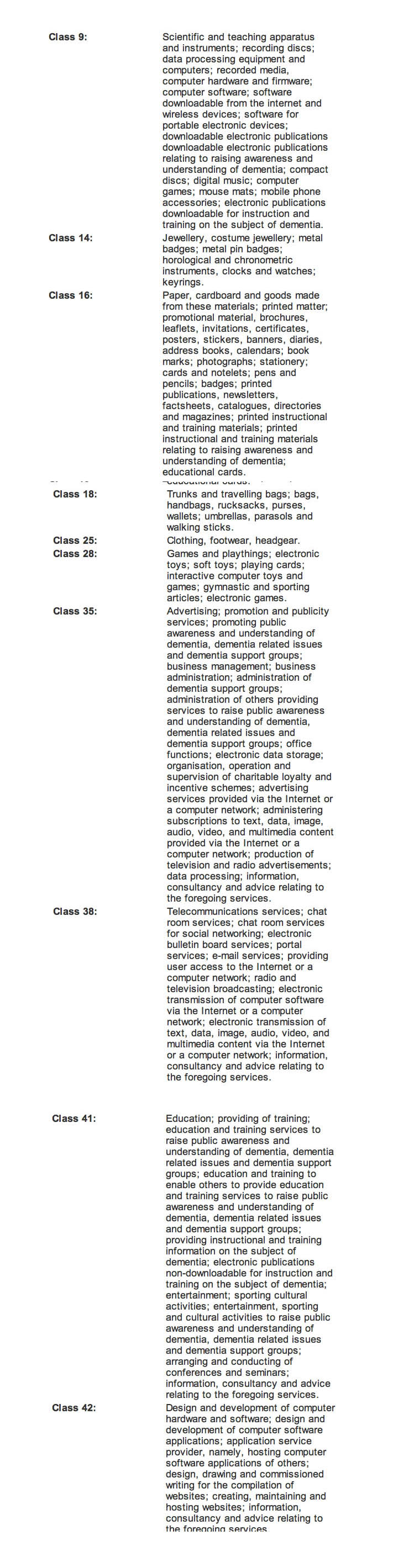

Last year, I got off my backside and published my first book on dementia. Called “Living well with dementia: the importance of the person and the environment“, the aim of it was not to sell the ideology of ‘person centred care‘. It was instead a well meant introduction to the original work of Prof Tom Kitwood and personhood, which has been pivotal in double declutching away from the Pharma stranglehood on dementia postdiagnost pathways. My point was that a person living with dementia had a past and present which were going to influence his or her future, and an interaction with the environment (such as the outside world or ‘built environment’, assistive technology, design of the home, design of the ward, dementia friendly communities) were major determinants of a positive wellbeing.

The book was broad-ranging, and I felt signified a change in direction of the narrative away from ‘treatments for dementia’. I also tried to cover in a balanced and fair way how the National Screening Committee had arrived at their original decision not to recommend screening for dementia. This decision has now been upheld. As it happens, I agree with the conclusion of the National Screening Committee, but for slightly different reasons. I feel a lot of people focus on the lack of sensitive and specific inexpensive screening tests – and this must be correct. But I also feel that because of the minimal effort to build up an extensive coherent evidence base on the effect of psychosocial interventions on living well with dementia, you are never going to be able to satisfy the last requirement, of improving morbidity (if you cannot improve mortality).

I have previously written about this here.

I essentially don’t want to rain on the parade of wanting to find a cure or effective symptomatic treatments before 2025. But this expectation, I feel, has to be much better, as the track record in developing treatments thus far has been poor. It is now well appreciated that G8 dementia was ultimately contrived as a reaction to Big Pharma on dementia, and it must be acknowledged, I feel, resources allocated into Pharma should not be at the expense of relatively inexpensive methods for promoting living well with dementia for people who are currently living with a diagnosis.

My original contents were therefore as follows:

Foreword by Professor John R Hodges; Foreword by Sally- Ann Marciano;Foreword by Professor Facundo Manes; Acknowledgements; Introduction; What is ‘living well’?; Measuring living well with dementia; Socio-economic arguments for promoting living well with dementia; A public health perspective on living well with dementia, and the debate over screening; The relevance of the person for living well with dementia; Leisure activities and living well with dementia; Maintaining wellbeing in end-of-life care for living well with dementia; Living well with specific types of dementia: a cognitive neurology perspective; General activities that encourage wellbeing Decision-making, capacity and advocacy in living well with dementia; Communication and living well with dementia; Home and ward design to promote living well with dementia; Assistive technology and living well with dementia; Ambient assisted living and the innovation culture; The importance of built environments for living well with dementia; Dementia- friendly communities and living well with dementia; Conclusion; Index.

The essence of my emotions about ‘living well with dementia’ is that living well with dementia is not a slogan to sell a product or service. It is a genuine change in philosophy from the medical model, of diagnosis and treatment, to one which requires a long term care revolution. As Prof Sube Banerjee said last year at the Dementia Action Alliance annual conference, we don’t need high volume diagnoses which are of low quality; although we all agree that it is unacceptable that people should be languishing for ages waiting for a diagnosis, and diagnostic rates of people who want to be diagnosed appear poor. We need high quality diagnoses. And even Baroness Sally Greengross, the Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group for dementia, readily admits that the post-diagnostic care and support could and should be much better.

Against quite a lot of resistance from people in the medical profession which at best was complete indifference and lack of recognition of my work, I found many people in the general public who have thanked me for my work. I am completely independent, so I do not draw an income from any of my work apart from minimal royalties for the book. I paid my way to go to all conferences I went to last year. I will again be paying my own way for travel and accommodation to go to the 30th Alzheimer’s Disease International conference in April 2015 in Perth, on “cure, care and the lived experience“.

I was specifically asked last year by a panel representing the General Medical Council which people had benefited the most from my book. They expected me to say Doctors, but in all honesty I reported that the book had been extremely positively received by caregivers and people with dementia.

And I was staggered when a colleague of mine sent out this innocuous tweet which was well receive which had 151 ‘favourites’.

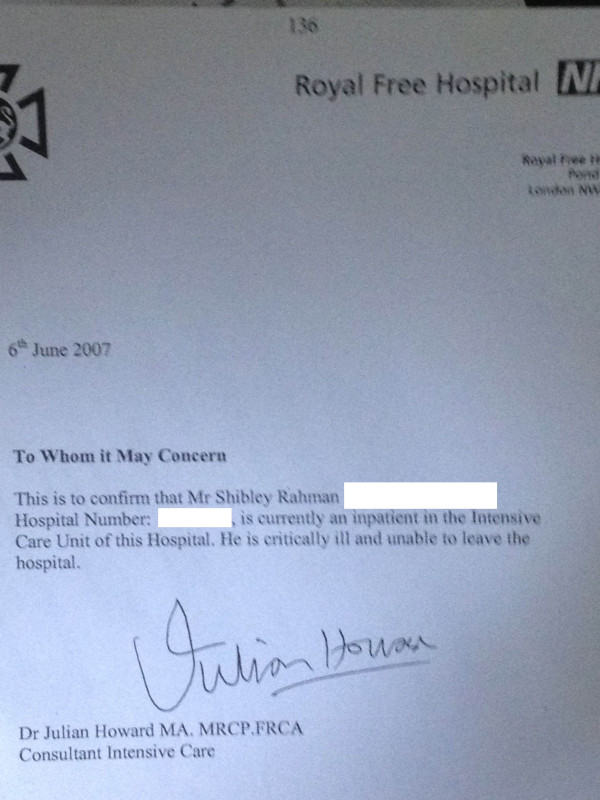

I do passionately want things to change for people with dementia and caregivers, but I don’t think of myself as a player in change. I don’t call myself anything in wanting change to living well with dementia; this is particularly because I really don’t believe in job descriptions or titles. I get fussy about the fact I am a person living well with recovery from alcohol, and physically disabled, but I am not ‘ill’ and as such I don’t see myself as a ‘patient’. I am on the medical register, but I do not feel defined by that (I have spent a few years not on the medical register due to consequences from when I was actually exhibiting symptoms of an illness). I have written numerous papers and two books on dementia, but I do not see my self as an ‘academic’. But I am hugely passionate about English and global policy.

I don’t want post-diagnostic care and support in my jurisdiction to be so haphazard. I totally sign up to the drive towards better inclusivity and accessibility for people with dementia, but I personally wouldn’t call this policy drive in this country or abroad “dementia friendly communities”. I would feel uneasy with a policy called “black friendly communities” or “gay friendly communities”, as these terms encourage division for me. Besides, I know from my personal experience with disability that all manifestations of disability are not necessarily evident to external observers. To take as an example, I see double all the time due to a problem with my brain, after my six week coma due to meningitis in 2007 when I was in a coma. But no-one, from looking at me, would know that. I understand that some people who are disabled, even if they fit the ‘criteria’ of the term, do not wish to call themselves ‘disabled’.

But the point is that there is now extensive legal advice about the relationship between equality and human rights law and mental health (for example chapter 3 in the new code of practice over the Mental Health Act just published). I have in fact been invited to be on a panel to review what I anticipate to be a very influential document looking at how the law is influencing dementia policy from the Mental Health Foundation early this year. Putting this stuff on a legal footing means that it’s a serious requirement for facilities to be more than aspiration in meeting ‘dementia friendliness‘; it then becomes a legal obligation. Under this view, one would provide adequate signage for people known to have spatial navigation difficulties from a dementia, in the same way that you might build a wheelchair ramp for employees who used wheelchairs in your company.

I feel that this narrative is moving my way, and in the direction away from being given your diagnosis and the conclusion ‘nothing can be done’. Kate Swaffer, in Australia, has elegantly articulated this in detail as “prescribed disengagement” (for an excellent article on this, please see here). Kate has also written a paper on stigma in the Dementia Journal, which is particularly interesting as Kate lives with a dementia herself.

It is a general ignorance of dementia that was thought to contribute to stigma and discrimination against dementia. I often ask London cabbies what they know about dementia; these individuals tend to be extremely well informed about many things, but I have found that unless they have a personal ‘connection’ with someone with dementia they can know very little (but are extremely regretful about not knowing more). The “Dementia Friends” in the UK jurisdiction had an aspiration of making one million ‘dementia friends’, a figure arbitrarily plucked out of nowhere, but presumably based on the successful Japanese “befriending” campaigns.

//www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/VD3epu4SB2Y

They had a target of one million ‘dementia friends’ by March 2015 originally, but I understand that this initiative will now run for the whole of the year. And, at the time of speaking, they look as if they might just make it, according to their website:

I am a “Dementia Friends Champion”. I did my own Ph.D. in dementia at Cambridge under Prof John Hodges. I was the first person in the world to suggest a cognitive method for diagnosing behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and explain its rationale. This paper is even cited in the chapter on dementia in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. I quite enjoy my sessions. I invariably get asked tougher questions in these sessions, which are well received, than I have ever received in academic conferences.

I have no doubt whatsoever that England will have its second national policy soon for 2015-20. An influential report from Alzheimer’s Disease International looked at the value of national plans in an excellent report last year. I have no involvement with the formation of the new strategy, but the composition of the group has been clearly provided.

Members of the ‘Dementia Advisory Group’ are:

- Chair Clara Swinson, Department of Health

- Deputy Chair Lorraine Jackson (Deputy), Department of Health

- Jeremy Hughes, Alzheimer’s Society

- Tom Wright, Age UK

- Helena Herklots, Carers UK

- Bruce Bovill, Carer

- Joy Watson and Tony Watson, person living with dementia and carer

- Graeme Whippy, Lloyds Banking Group (representative from the PM Challenge Dementia Friendly Communities Champion Group)

- Sarah Pickup, Hertfordshire County Council (representative from the PM Challenge Health and Care Champion Group)

- Martin Rossor, UCL (representative from the PM Challenge Research Champion Group)

- Paul Lincoln, UK Health Forum

- Helen Kay, The Local Government Association

- David Pearson, The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services

- Hilda Hayo, Chief Executive of Dementia UK

- Graham Stokes, Chair of Dementia Action Alliance

- Dawn Brooker, The University of Worcester

- Martin Knapp, London School of Economics

- Tim Parry, Alzheimer’s Research UK

- Simon Chapman, National Council for Palliative Care

- Jill Rasmussen, Royal College of General Practitioners Dementia Champions

- Martin Green, Care England

- Bridget Warr, UK Home Care Association

The terms of reference are here.

It is stated that the Advisory Group will:

1. Review the evidence on progress on dementia care and support over the last five years to identify where progress has been made, key challenges and gaps and priorities for action. This will include looking at the evidence on risk reduction and how the incidence of dementia could be reduced.

2. Consider what success could look like by 2020 in the following broad areas:

- Improving the provision and continuity of personalised health and social care for people with dementia and carers – this includes risk reduction, prevention, diagnosis, post-diagnostic support, the role of technology and new models of care.

- Promoting awareness and understanding.

- Building social engagement by actions of individuals, communities and businesses.

- Boosting dementia research capacity and capability, the opportunity for individuals to get involved in research and optimising knowledge transfer and pathways to impact.

- Improving support for carers including improving their health, wellbeing and experienc

- Cross-cutting: Supporting the education, training and development of the health and care and wider workforce.

- Cross-cutting: Global action on dementia

- Cross-cutting: Ensuring equity of access, provision and experience

This will include looking at what we can learn from international evidence and experience.

I feel that this would form a coherent strategy.

Whilst traditionally, it might be useful to consider campaigning for dementia in terms of ‘cure’, ‘care’ and ‘prevention’, in reality living well with dementia potentially straddles all three areas.

I believe it’s extremely important to have a large body of people with dementia and carers report back on what their needs are. Such committees have had a long history of involving people with dementia and carers which might appear tokenistic. The World Dementia Council has not even appointed a person living with dementia to sit regularly on their Council.

As far as future post-diagnostic care and support is concerned, we clearly can no longer have a situation where, once a diagnosis is made, some people with a diagnosis, friends and family are totally lost in the system, or even at worst lost to follow up. There appears to be little coordination of care, and sometimes there’s more signposting to services than actual services. There seems to be little coordination of information held for practitioner and professional care in primary and secondary care, and between health and social care. We have a ridiculous situation where people with dementia, some of whom can do very badly when they are admitted to hospital partly due to a distressing change in environment, cannot be discharged in a timely manner from hospital due to social care cuts in service provision.

There is a clear drive to person-centred care, and I feel a very good way of discovering personhood is to adopt a ‘life story’ approach. I anticipate that networks for life story and carers will be invaluable during the lifetime of the next parliamentary term 2015-20.

The current Government has continued with the longstanding policy drive towards personalisation promoting ‘choice and control’. However, there are nuances to how policy can be implemented; for example a rights-based advocacy approach might be considered by some preferable to the promotion of personal budgets, which poses issues about the lack of universality of care, scope for co-payments, further marketisation, and complete lack of choice if you run out of money.

The next Government will be bequeathed developments in the handling of NHS data for service care provision, and of course the new Care Act. Some reflections are here on the Care Act:

//

I feel the the main challenge, in my opinion, in policy is to introduce safely and in a competent way “whole person care“. It’s going to take a lot of bottle to integrate properly health and social care, with all the challenges which endure, including breaking down organisational boundaries, cultural silos, facilitating competent knowledge sharing sand transfer, and a complete cultural change unfreezing from the biomedical model to one which recognises abilities not making feel inadequate because of their disAbilities. I would very much like to see the medical profession put some effort into the annual ‘follow up’. The point of this check up is not to chart with meticulous accuracy has changed in brain scans, psychology, or blood tests, meritorious though these initiatives are. The point about these follow ups is to ensure that there is a synchronised system of post-diagnostic care and support and everything is being done to improve living well with dementia (for example encouraging social networks and mitigating against social isolation). I feel personally the next Government should implement a “year of care” for dementia.

This change can only come from a social movement led by the major stakeholders themselves – people living with dementia and caregivers. A “top down reorganisation” will not work.

And I would prefer leaders in dementia not to be a Prime Minister but in fact to a person living with dementia. I think that way the needs of people currently living well with dementia will be better addressed, not just in service provision but also in research spend. I believe strongly that people newly diagnosed should have access to ‘dementia advisers’ and a properly resourced network of clinical nursing specialists. These nursing specialists are vital in pro-active case management, but the evidence base does need exploring further. The development of the personalised care plan, which can hopefully avert crises to encourage relaxed effective care out of hospital where possible. I have written about dementia specialist nurses, previously, here.

My interests are reflected in my new book ‘Living better with dementia: looking to the future’ due to be published on June 18th, 2015.

The contents are here.

1. Introduction. 2. Framing the narrative for living well with dementia. 3. Thinking globally about living well with dementia. 4. Culture and living well with dementia. 5. Young onset dementia and living well with dementia. 6. Delirium and dementia: are they living well together in policy. 7. Care and support networks for people living with dementia. 8. Introduction to autonomy and living well with dementia. 9. Can living well with dementia with personal budgets work? 10. Incontinence and living well with dementia. 11. Nutrition and living well with dementia. 12. Art and creativity in living well with dementia. 13. Reactivating memories and implications for living well with dementia. 14. Why does housing matter for living well with dementia. 15. Networks, innovation and living well with dementia. 16. Promoting leadership. 17. Seeing the whole person in living well with dementia. 18. Conclusion.

I think this book is more ambitious than the first one. In keeping with my original research interests, I consider why art and music are so important for living well with dementia. I also propose a new theoretical framework, the first in the world to my knowledge, why reactivation of “sporting memories” works. The “Sporting Memories Network” has been a very impressive initiative thus far in promoting wellbeing.

//www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/rfjludYyeZU

Finally, I wish everybody luck in formulating our new English dementia policy to be implemented within the lifetime of the next Government. It is imperative that the views of the community of people living with dementia and the army of approximately 5.4 million unpaid caregivers are prioritised above the needs of others, I feel, above all.