The “doing more with less” mantra of course very popular as a solution to the impending doom of having to treat the old fatties with a burgeoning technology budget. Re-engineering the health system has become a hobby of thinktankers, in the best spirit of the blind watchmaker. But policy wonks are still unable to escape from the fact that the NHS is not a widget factory. The management school of Frederick Taylor is totally unfit for purpose in considering outcomes rather than outputs. As national policy moves steathily towards promoting wellbeing, particularly in long term conditions, the question becomes, “what is a good outcome for a person with dementia?” Econometrics, and people in big corporates, will immediately point to costs, such as the financial cost of ‘unplanned admissions’. However, the “tide is turning” on all that. People are becoming interested in empowering people with dementia to lead fulfilling lives, building on what they can do. It is however inherently undermined by people wishing to abuse the system, such as large companies returning massive shareholder value and paying their staff pittance on zero-hours contracts. Everyone also knows the system only can survive through the large army of unpaid family caregivers.

At a time when Don Berwick was in fact Donald M Berwick president of the “Institute for Healthcare Improvement”, before he became ‘even more famous’, he published, “Measuring NHS productivity: How much health for the pound, not how many events for the pound” in the BMJ on Saturday 30 April 2005. Berwick reported that the ONS had recently concluded that NHS productivity had declined by 3-8% (depending on the method of calculation) between 1995 and 2003. This had led Berwick cheekily to ask, and most pertinently to ask, ““Production of what?” is the key question here. If we ask the wrong question the answer may lead us to the wrong policy conclusion.”

Berwick noticed that the method used thus far was fundamentally flawed.

“it does not assess improvement in the mix of these so called outputs, such as when innovations in care allow patients to be treated successfully in outpatient settings rather than in the hospital. To its credit, the ONS notes carefully that “the output estimates do not capture quality change.” Its interpreters need to show equal caution.”

Berwick concluded,

“The people of the UK should be not asking, “How many events for the pound?” but rather, “How much health for the pound?” At least, that is what they should ask if they desire an NHS that can keep them healthy and safe at an affordable price for as long as is feasible.”

Wind on five years, and John Appleby, Chris Ham, Candace Imison and Mark Jennings gave birth to “Improving NHS productivity: More with the same not more of the same” from the King’s Fund on 21st July 2010. You can view it from here, if you wish. Efficiency, in true Frederick Taylor, was the name of the game again.

“As the evidence brought together here shows, there is huge scope for using existing expenditure more efficiently, in relation to both support and back-office costs, and particularly variations in clinical practice and redesigning care pathways. It should be noted that the actual sums identified as potential savings may have already been partly achieved by the programmes listed, and so the figures should be interpreted as an indication of the scale of potential savings rather than an absolute figure.”

Of course, the language of efficiency is totally laughable in the private sector with finding profit in repeated work and unnecessarily transactions. As the NHS lives in denial that its budget is not being squeezed, as £20bn is returned to the Treasury from “efficiency savings”, pursuing efficiency has been ‘a means to an end’, and, together with the zest for austerity, perpetuates the notion that NHS needs to dramatically cut budgets, reduce systematically services for patients and sack staff.

In his 2008/9 Annual Report, Sir David Nicholson prepared the NHS to plan ‘on the assumption that we will need to release unprecedented levels of efficiency savings between 2011 and 2014 – between £15 billion and £20 billion across the service over the three years’. These figures were based on analysis by the Department of Health, which assumed zero real growth from 2011/12 to 2013/14 in actual funding for the NHS in England. Given the state of the handling of the economy by the current Government, this was in fact quite a good assumption. It set this against spending that would be required to meet – as Nicholson reported (Health Select Committee 2010) – demographic changes, upward trends in historic demand for care, additional costs of guidance from NICE, changes in workforce and pay, and the costs of implementing government a £2.4bn non-“top down reorganisation” policy. Hence, the resultant ‘gap’ between actual and required funding of between £15 billion and £20 billion by 2013/14. Talking optimistically that is..

For dementia, there are other factors at play. With unified integrated budgets, or “whole person care”, it might be difficult to identify where the cutbacks are, as the figures merge into a morasse of confusion. Slimming the State might give a blank cheque under such a construct completely to annihilate social care. And against this background “self-care” – helping patients to better manage their own condition – has been promoted as being effective in reducing emergency admissions, including the use of care planning. At worst, “self care” is a figment of the Big Society which is a turkey which never flew.

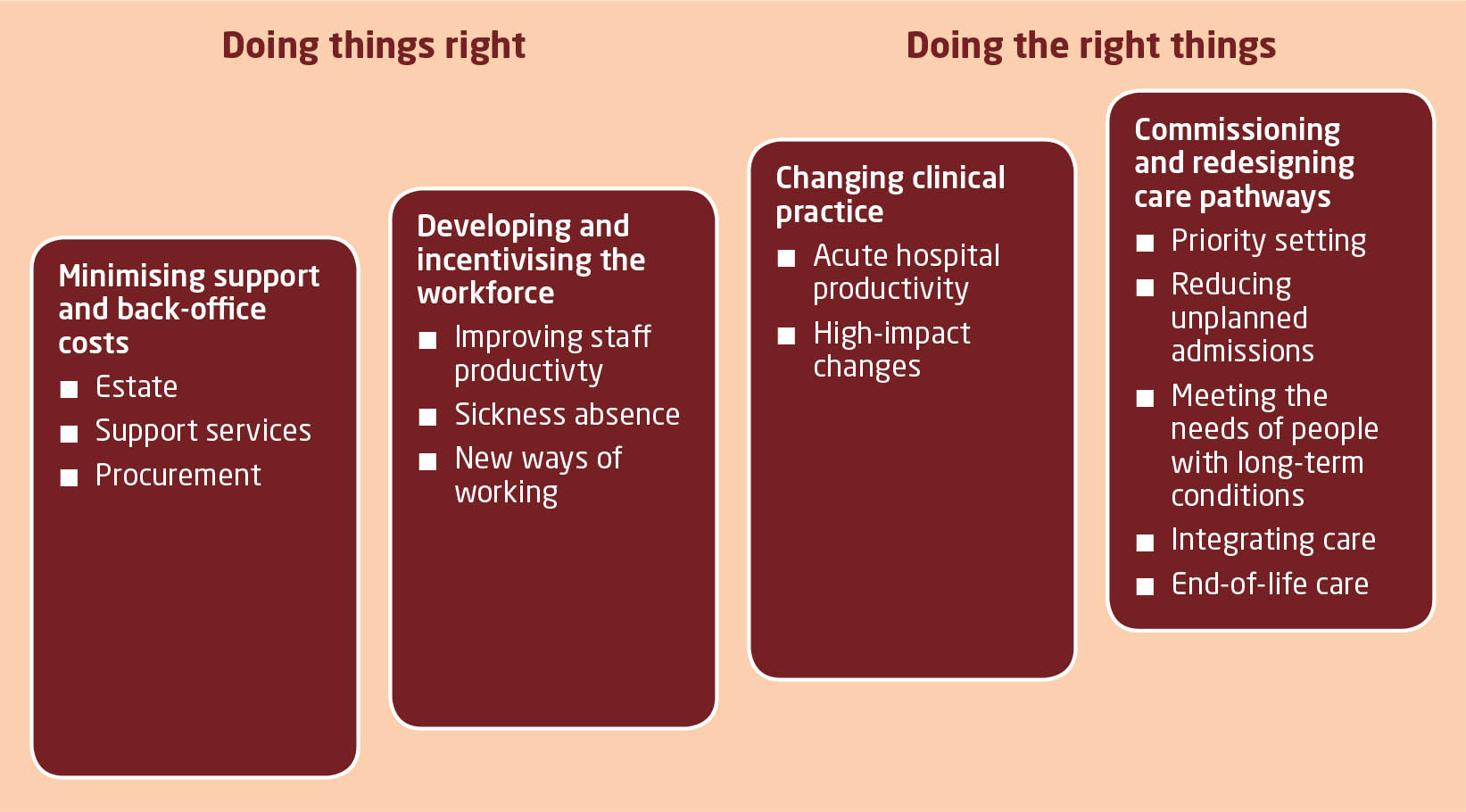

So in that report from the Kings Fund various leadership and management devices are identified in relation to a productivity squeeze, of relevance to “the funding gap”:

A practical example of the benefits of integration along the pathway of care can be seen in Torbay, where health and social care integration has had a measurable impact on the use of hospitals. Torbay has established five integrated health and social care teams for older people, organised in localities aligned with general practices. Health and social care co-ordinators liaise with users and families and with other members of the team in arranging the care and support that is needed. Budgets are pooled and can be used by team members to commission whatever care is needed.

And – if productivity for dementia is extremely difficult to quantify, especially if you’re doing “more with less”, what about the general economy? According to NEF, recent estimates of productivity have told a familiar story: output per hour worked fell by 0.3% over the middle part of 2013. This means whatever economic growth occurred over the last year was not the result of people working better, or more efficiently. It was the result of an increase in the total number of hours worked. Productivity, over the whole year, barely improved. Roll over Taylor.

Labour productivity, the amount of economic output each worker generates per hour, fell sharply in the recession and has remained very weak. Employers hung on to workers when output fell and hired more people when the economy was stagnant. Productivity levels have remained relatively unchanged since the beginning of 2008. The difference between this and the three previous recessions is stark. And that is “the productivity puzzle”. ONS research has concluded that there is no single factor that provides an explanation, but identifies several that may have contributed.

Of particular scrutiny from economists has been something which has been enigmatically called “the changing nature of the workforce”. Firms have less need to fire people if pay rises are modest or if they are willing to work fewer hours. It is called “labour hoarding”, where employers hang on to more workers than they need in a downturn, so that when there is a recovery they can respond quickly, without incurring the costs of hiring and training new people. In a paper published published by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, researchers found many factors affecting productivity. They foud little evidence that the overall fall has been caused by labour hoarding, the demise of financial services or changes in workforce composition. Instead, we conclude that the key contributing factors are likely to be low real wages, low business investment and a misallocation of capital. But there’s always been one particularly attractive theory: “flexible” labour markets have been proved to be very effective in delivering part-time and temporary work, at low cost to employers. This is where market forces can lead to exploitation.

A “zero-hour contract” is a contract of employment used in the UK which, while meeting the terms of the Employment Rights Act 1996 by providing a written statement of the terms and conditions of employment, contains provisions which create an ‘on call’ arrangement between employer and employee. It does not oblige the employer to provide work for the employee.The employee agrees to be available for work as and when required, so that no particular number of hours or times of work are specified. The employee is expected to be on call and receives compensation only for hours worked. And they are popular – one survey suggests that up to 5.5m people are now working on a zero hours basis. Meanwhile, underemployment – those who would like to work more hours, but cannot – is at record levels. When faced with collapsing markets in the recession, employers – rather than reducing the number of people in work – effectively cut wages and hours of those working.

Doesn’t this sound perfect for addressing the NHS funding gap in dementia?

Reviewed by Roger Kline, several reports have made clear that recent changes in employment practices are undermining safe and effective care outside hospitals. In particular, according to Skills for Care, 307,000 social care workers are now employed on zero-hours contracts under which staff have no guaranteed hours (or income) and travel time is unpaid. This accounts for one in five of all professionals in this sector and the numbers are growing rapidly. Also, it is argued that “personalisation” has led to a growth of a section of the homecare workforce with virtually no employment rights at all – often on quasi self-employed terms – as well as raising serious questions about support, quality, training and supervision. All parties have been keen to pursue personal health budgets. It may be a coincidence that all parties agree on the need for the “efficiency savings”.

So the parties are largely singing from the same hymn sheet, and it is hard to know whether the think tanks have led to a discussion which airbrushes zero-hours contracts and unpaid family caregivers in dementia. In discussions of integrated care from think tanks, albeit in various guises such as “Making best use of the Better Care Fund” from the King’s Fund or “Whole person care” from the Fabian Society, there is a distinct unease about talking about the army of unpaid family caregivers, without whom many agree the care system would collapse, or those low-paid carers on zero-hours contracts. Converging evidence from the macroscopic picture of our economy, in the form of the ‘productivity puzzle’, and the landscape of social care for dementia paints in fact quite a grim picture of legitimising a solution to “the funding gap”.

This solution implemented has not in fact “doing more with less”. It’s been “doing a lot with virtually nothing”. And whatever your precise definition of ‘productivity’ for these workers, it is clear that many are at breaking point themselves under consider psychological and financial pressures themselves. Shame on no-one for discussing this with the general public.

Exploitation of carers should not be the solution for solving “the funding gap”.