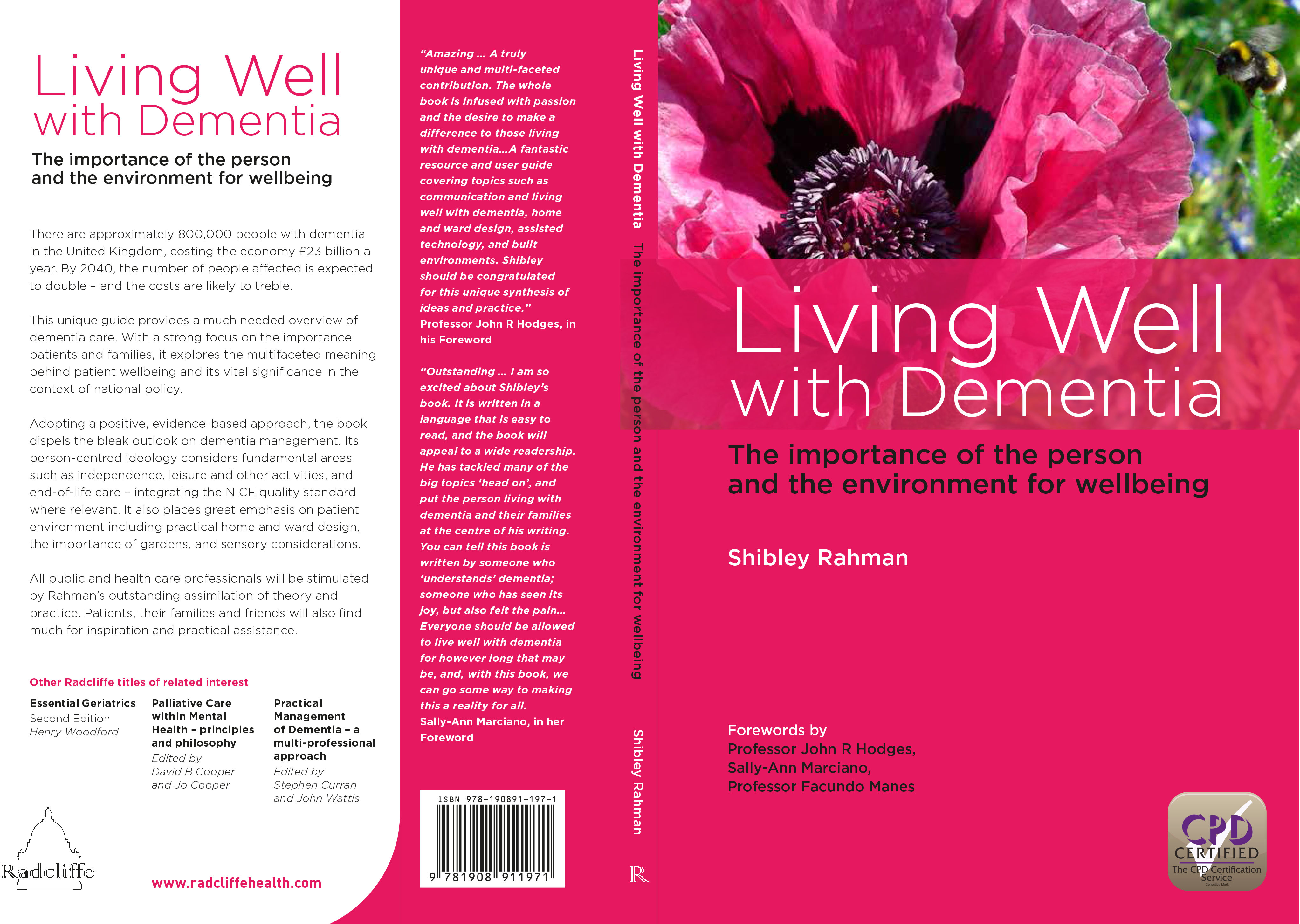

Recently, my friends have been trying to motivate me to tell me that I should consider writing and researching about the quality of life as a full time job. I had recently been feeling as if my work was being largely unnoticed, compared to the usual players who frequent the conferences and the limelight. So it genuinely was a massive shock that my first book ‘Living well with dementia: the importance of the person and the environment’ was judged as first in the category of health and social care for the BMA Book Awards 2015. The book was published in January 2014, and remains one of the few books which gives an overview of the living well with dementia approach in English dementia policy. It’s fair to say that medics exhibited challenging behaviour in reaction to it, as it was the counterpoint to their comfortable medical model of dementia. I instead set the scene effectively for my second book ‘Living better with dementia: good practice and innovation‘ which is a more discursive look at the social model of disability, and its implications for domestic and global policy. I once told one of my regulators, the General Medical Council, that I had received excellent feedback on the book including from people living with dementia. I should like to mention particularly Kate Swaffer and Chris Roberts, who have always remained clear, from the outset, that they enjoyed the book and thought it to be of very high quality. This has kept me highly motivated, even when I have been feeling frustrated at the whole initiative.

I should like also to thank Prof John Hodges, Prof Facundo Manes and Sally Ann Marciano, who kindly did me the honour of writing the Forewords for this book. They can be viewed here.

The BMA Medical Book Awards take place annually to recognise outstanding contributions to the medical literature.

Prizes are awarded in 21 categories, with an overall BMA Medical book of the year award made from the category winners.

The judging panel awards books for their applicability to audience, production quality and originality.

The BMA Medical Book Awards were held on Thursday 3 September 2015

Download the 2015 Book Awards ceremony programme

The full list of prizes by category is here.

Category result

Health and social care

Community care, health promotion, health prevention, management, health services, medico-politics, medico-legal medicine, social medicine.

First prize

- Living Well with Dementia: The Importance of the Person and the Environment for Wellbeing

Shibley Rahman—Radcliffe Publishing, January 2014. ISBN: 9781908911971. £29.99

Highly commended

- Evaluating Improvement and Implementation for Health

John Øvretveit—McGraw-Hill Education/Open University Press, August 2014. ISBN: 9780335242771. £26.99 - Human Factors in Healthcare: Level 1

Debbie Rosenorn-Lanng—Oxford University Press, February 2014. ISBN: 9780199670604. £24.99 - Seeing Beyond Dementia: A Handbook for Carers with English as a Second Language

By Rita Salomon—Radcliffe Publishing, January 2014. ISBN: 9781846198922. £21.99 - The Cities Report

by UNAIDS—UNAIDS, December 2014. ISBN: 9789292530662. Free - The Sociology of Health and Medicine: A Critical Introduction 2nd Edition

by Ellen Annandale—Polity, August 2014. ISBN: 9780745634623. £22.99

What the judges said:

Living Well with Dementia: The Importance of the Person and the Environment for Wellbeing

Shibley Rahman – Radcliffe Publishing, January 2014 ISBN: 9781908911971 £29.99

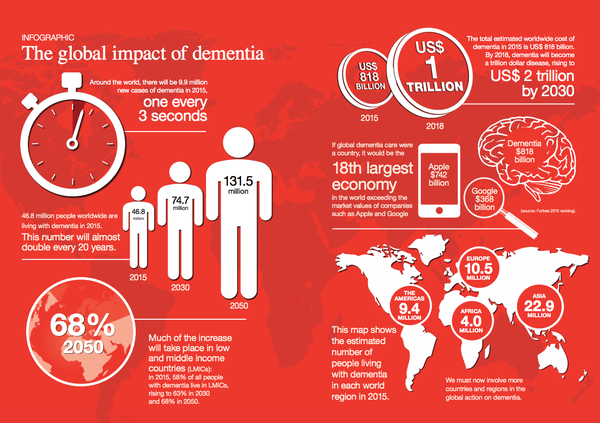

All public and health care professionals, patients, their families and friends

This unique guide provides a much needed overview of dementia care. With a strong focus on the importance of patients and families, it explores the multifaceted meaning behind patient wellbeing and its vital significance in the context of national policy. Adopting a positive, evidence based approach, the book dispels the bleak outlook on dementia management. Its person-centred ideology considers fundamental areas such as independence, leisure and other activities, and end-of-life care – integrating the NICE quality standard where relevant. It also places great emphasis on patient environment including practical home and ward design, the importance of gardens, and sensory considerations. The objective is to examine the number of people in the UK who currently have dementia and the cost that this places on the health care system. In addition to analysing the scale of this condition, it touches on the experiences of a person with dementia and how this effects their family, friends and those caring for them in an effort to prepare those facing this diagnosis. This unique guide provides a much needed overview of dementia care. Offers a highly practical and unique assimilation of theory and patient-centred practice.

“I would recommend this book 100%. It just makes sense to read. This will appeal to so many professionals going to be involved in the care of the elderly. And anyone who is doing research in this field should go through this book too. It brings together so many aspects of dementia care under one setting: an amalgamation of resources and guidelines. This book is targeted at anyone who is interested in public health, end-of-life care, dementia management and anyone in geriatrics really. It is a contemporary evidence-based textbook which brings together the concept of ‘wellbeing’ in the field of dementia care. This book is a really good read for any clinician who deals with elderly patients as it really opens your eyes to a the outside factors which play such a massive role in the care of the patient, such as the wellbeing of the carer, the psychological aspects of care, the public health perspective, economic aspects and so on. It also gives really thorough reference lists for every chapter so that it is very easy to go in to read a chapter and then look up the data to support it. It is an adequately easy read, there are many definitions. The layout of the book makes it easier to look up specific chapters without having to read everything before, but it also reads well if you read the whole book. I think this book would work well for anyone who is writing a dissertation, public health, or anyone who is doing a presentation on this topic as it is a very resourceful and complete book. The book really goes through all its objectives in a very clear and thorough manner. It is about the multifaceted approach to dementia care, and how to maintain this wellbeing of the patient, care changes, as does requirements and expectations as the disease progresses. As clinicians there are many things we can take from this book and apply to daily practice. For example, when a patient is been seen, it would be worthwhile making sure that the carer/family member is also managing as they found that the ‘psychological health of carers of people with dementia was impaired with social interaction and recreation most affected’. It is also a very good reminder for anyone who already practices well. The thing with dementia care is that, medical textbooks only really cover the types, pathologies, diagnosis and management where, really the contents of the whole of this book comes under a small paragraph as ‘social care/financial care/respite care/end-of-life’. But in reality, it is this whole idea of the wellbeing of the patient and their support network that we are working towards, and it does not stop at diagnosis and sending them away with a few things to take and do. This book opens your eyes how extensive dementia care can be. It is a complete text on the multifaceted approach to wellbeing although order to make it 100% complete, maybe a chapter on the classic dementia signs, symptoms, progression, pathologies, diagnoses, treatments.”