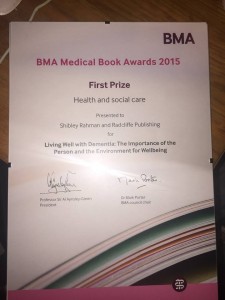

I am very honoured that the main foreword will be by Prof Sube Banerjee, Chair of Dementia at Brighton and Sussex Medical School.

Sube is very influential in English dementia policy. His contributions have been outstanding. Indeed, he co-authored the original English dementia strategy ‘Living well with dementia’ in 2009 on behalf of the Department of Health.

I am very honoured that the other two forewords are to be by Lisa Rodrigues and Lucy Frost, who have substantial interest and knowledge in dementia.

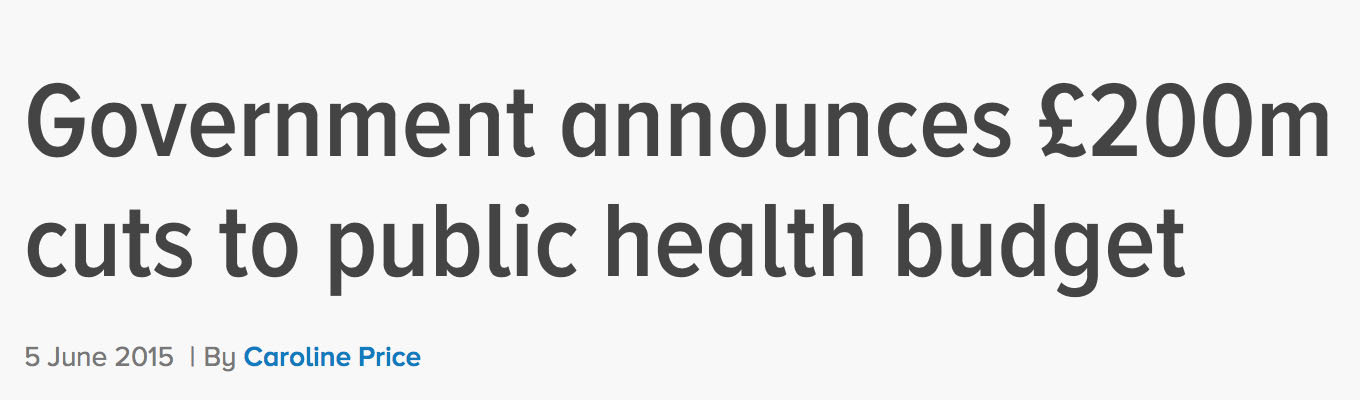

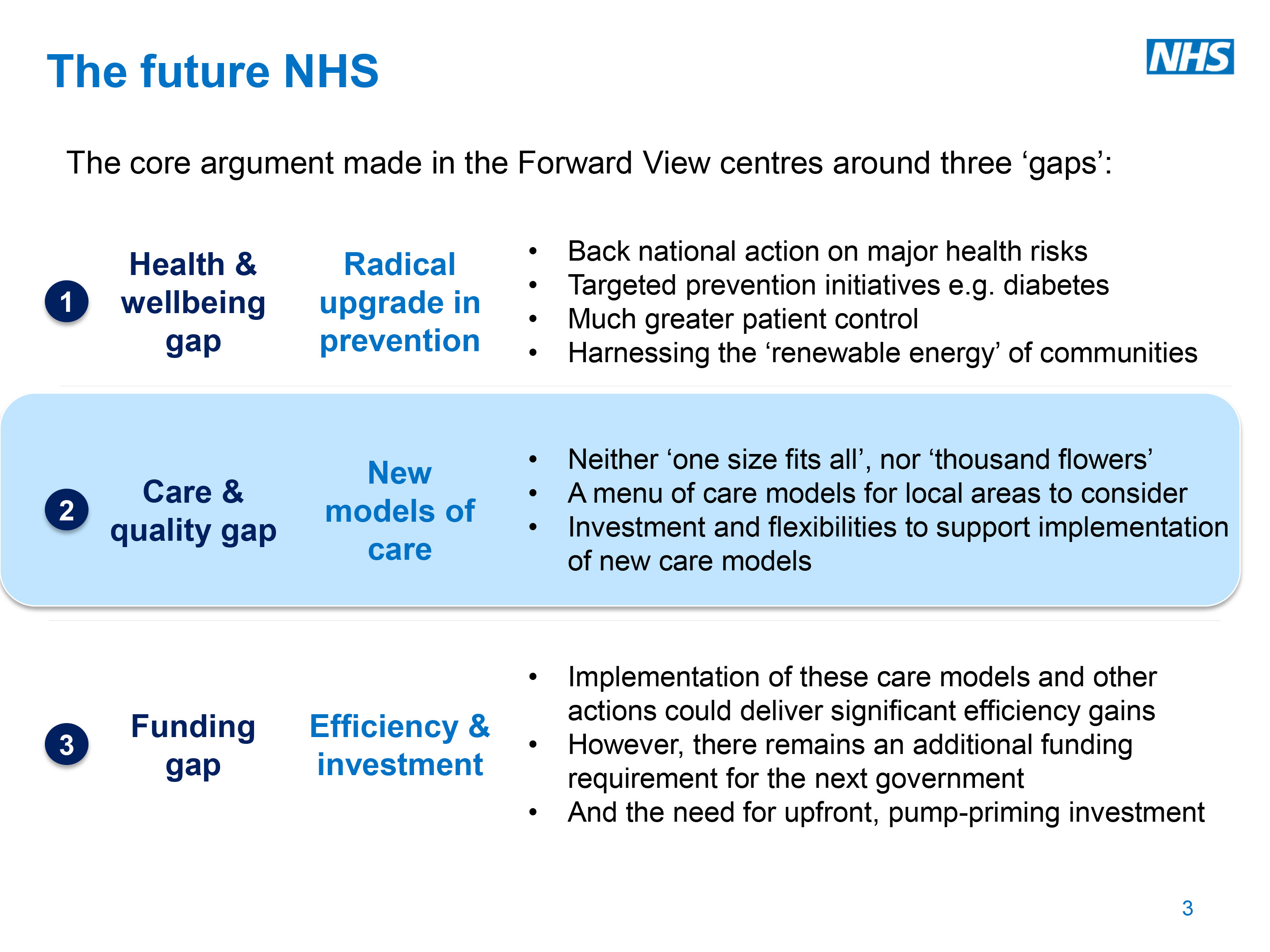

The book will be a timely look at the evidence, with many of the topics being rehearsed elsewhere in policy, such as the NHS Five Year Forward View, or the NICE guidance on dementia (currently in development).

This book is likely to be published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers in the end part of 2016.

Chapter 1 : Overview

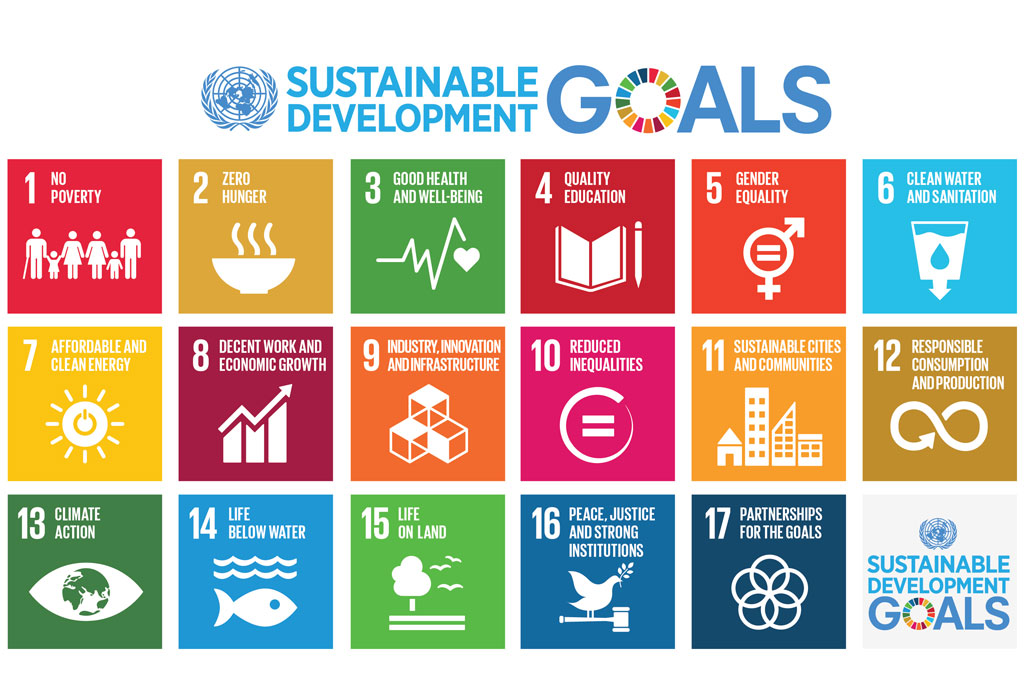

I will draw on the existent literature to consider what has emerged about a consensus about ‘care pathways’ for dementia, in particular the events which can lead up to “crises” or transfer to a residential settings. There has not been an adequate look at the work up in primary care for dementia, and I will consider how domestic policy might be harmonised with international guidance. In the presence of an evidence base for dementia advisors and dementia support workers, I will consider the potential of signposting to services. I will re-visit the evidence base for prevention of dementia, and the current evidence base for the use of cholinesterase inhibitors and other drugs, but will concern myself with the impact of human rights, disability and sustainable communities in current thinking. The largest part of this chapter will be considering quality of care, and novel approaches such as integrated personal commissioning and the personal medical care home. Throughout the book, there will be a detailed discussion of the need to promote the health and wellbeing of carers, both paid and unpaid, and to consider coping strategies which might help through clinical specialist nurses and social care practitioners, and other colleagues.

Chapter 2 – The caring environment and culture

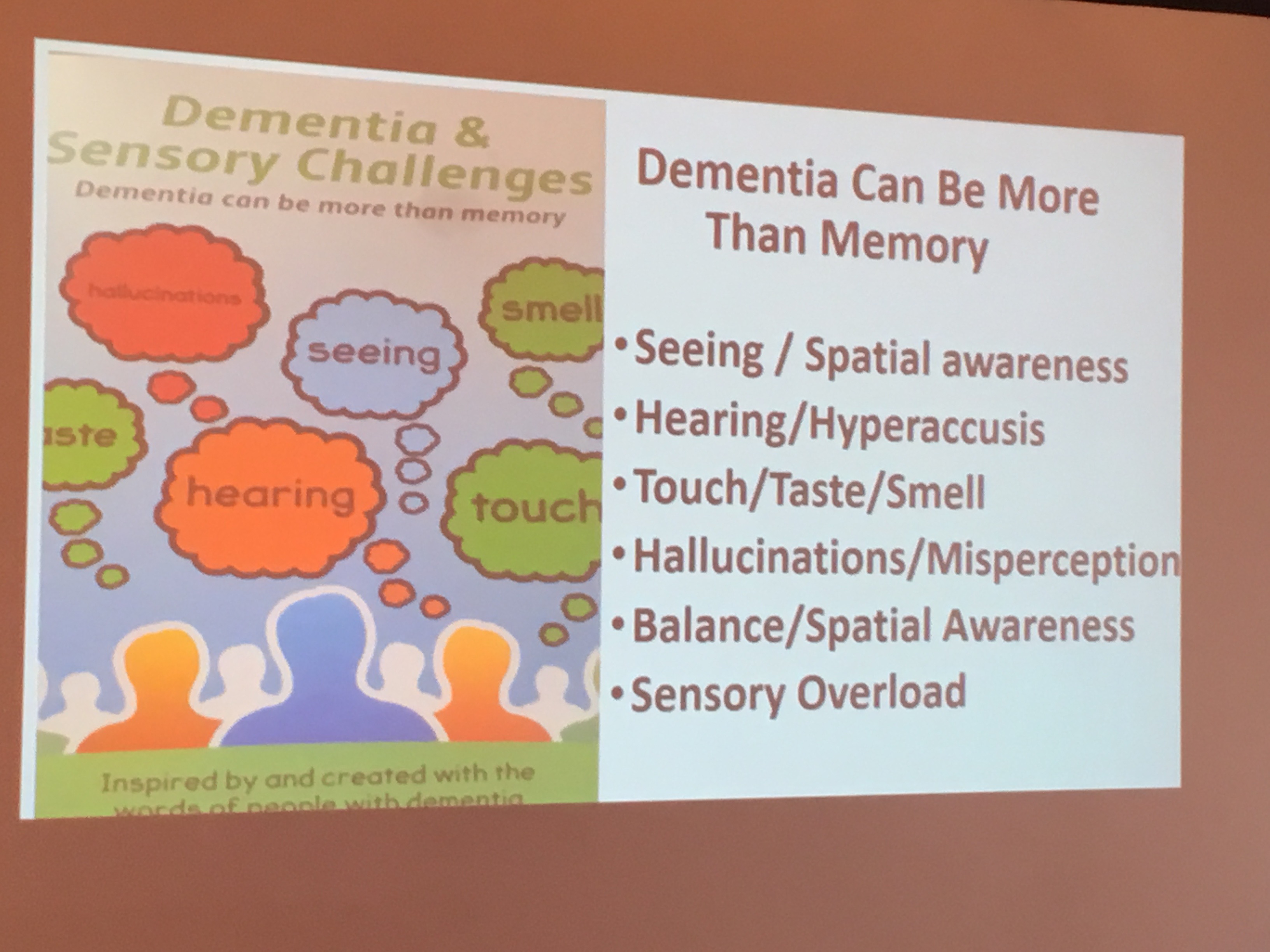

This chapter will explore evidence for the components of the built environment and sensory stimulation and enhancing person and relationship centred care which enhance health and wellbeing across care settings. The main emphasis will be on considering what change might be needed, and under what leadership from all stakeholders, to ‘improve’ services, howeverso defined, and the rôles that risk and innovation might play in the future. If there are truly ‘no more throwaway people’, this chapter will also include how the social capital from people with dementia and carers might be consolidated to build more resilient communities co-designing research and services.

Chapter 3 : Physical health and aspects of pharmacy

Enhancing physical health is essential across all different care settings. This chapter will review the current evidence for management of falls, frailty, pressure sores, urinary tract infections, and hip fractures, as well as aspects of nutrition and metabolic medicine, from a multidisciplinary perspective, emphasising the role for allied health professionals. Aspects of prescribing will also be considered, including overuse, underuse and inappropriate use of medications, and what evidence base has thus far built up in the area of ‘therapeutic lying’ and its ethical implications.

Chapter 4 : Wellbeing and mental health

This chapter will consider aspects of mental wellbeing, including self and identity, and awareness and insight. Its will also consider various other issues to do with mental health, including agitation, apathy, depression, and sleep.

Chapter 5 : Cognitive stimulation and life story

A substantial evidence base has built up concerning non-pharmacological approaches to dementia. This chapter will consider diverse approaches including cognitive stimulation, reminiscence work and cognitive neurorehabilitation. This chapter will also consider the evidence base for ‘life story’ and how it has been approached across various care settings.

Chapter 6 : Oral health and swallowing difficulties

This chapter will consider a much neglected area of health and wellbeing, relevant to holistic health and wellbeing, that of oral health and disease. Current important issues in this field will be considered, including dysphagia and mastication, as well as possible areas of interest for the future.

Chapter 7 : Activities

This chapter will evaluate critically what exactly is meant by the term ‘meaningful activity’, and consider whether reframing of the narrative, such as promoting creativity’ might be more helpful. The chapter will discuss the importance of communication across this area, but consider specifically the arts, drama and theatre, dancing, gardening and outdoor spaces, humour, and music.

Chapter 8 : Spirituality and sexuality

Identity and relationships have emerged as key themes across various conceptualisations of personhood, including of course Tom Kitwood’s. This backdrop will be presented at first, before considering key issues in sexuality, spirituality and religiosity, not only in life after a diagnosis, but also for enhancing health and wellbeing across all health and care settings.

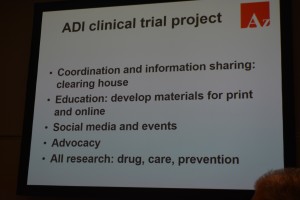

Chapter 9 : Research, regulation and staff

Research and regulation are examples of ‘work in progress’. This chapter will consider the key directions of research in the dementias, both qualitative and quantitative, across various care settings. This chapter will also consider specific areas of interest, including barriers to drug development including regulation. The overall area of regulation will be considered in terms of proportionality, and celebrate areas of good practice. The chapter will also consider areas which also are of utmost importance such as abuse and neglect, and adult safeguarding in general. The chapter will also include a discussion of how the health and wellbeing of staff might be promoted better to meet the needs of people with dementia and carers.

Chapter 10 : Care homes in integrated care

There have been various fashions and fads in thinking about ‘integrated care’, and part of the problem has been the plethora of different perspectives and models. This chapter will adopt a practical perspective of people living with dementia and carers having their health and wellbeing attended to in the right place, right way and the right time, and consider various aspects concerning this. Consequently, the discussion will emphasise advance care planning, attending hospital, admission and re-admission, avoiding hospitals, care transitions, case management, the “future hospitals” initiative from the Royal Colleges of Physicians, improving patient flow, intermediate care and discharge, liaison psychiatry and CMHTs, specialist clinical nurses including Admiral nurses, and “virtual wards”.

Chapter 11 : Independence

This chapter will consider some important diverse areas which intend to promote independence, their progress and impact in overall policy. These include electronic medical and care records, “individual service funds”, and reablement. This chapter will also consider potential opportunities and risks from personal genomics and personalised medicine.

Chapter 12 : Palliative care and end of life care

It is beyond dispute that palliative care and end of life care are essential components of promoting health and wellbeing in people living with dementia and carers. Person-centred care, maximising continuity of care, is fundamental. This chapter will consider the special features of this approach which are very important, and also consider why there has been a reluctance amongst some to consider dementia as a terminal illness. The chapter will also consider the significance of grief, and also consider a possible notion of ‘pre-grief’.

Chapter 13 : Living at home

The first twelve chapters are very relevant to the final chapter on living at home. Whilst much of the media attention is on care homes and nursing homes, or residential settings in general, there is remarkably little focus on living at home, including living at home alone, despite enormous interest in this amongst the general population. This chapter will consider how this approach may have evolved from the philosophy of ‘successful aging in place’, and consider how specific home environments might be enhanced including extra care environments. This chapter will include discussion of, specifically, community nursing including Buurtzorg Nederland, day and respite care, self management. telehealth and technology, and smart homes. The pivotal role of social care and social work will be emphasised throughout.