The legal considerations of the case of framing a global response as ‘dementia friendly communities’ are not insubstantial.

‘Dementia friendly communities’, as such, were “sold” in England as an army of new ‘dementia friends’, emulating the caravan befriending of Japan, producing pledges in a mass social movement about making life better for people with dementia.

But it turns out it is more than that.

The communities are intended to promote independent living, by being inclusive and accessible. They therefore fall under the remit of equality. But the undercurrent of this is that people living with dementia need to be pulled up to an equal standard, irrespective of their type of cognitive deficits which characterise the dementia.

This is a double-edged sword. Under the ‘social model of disability’, people living with dementia living with cognitive deficits can be equipped with cognitive aids to help them overcome impairments resulting from their cognitive disability.

But this incompletely addresses diversity of thought amongst people diagnosed with dementia. Diversity can be embraced in a positive way by employers with the right mindset. For example, people with memory problems can be re-employed in a job where memory is not a big component or where memory aids enable the job to be done.

The label of ‘dementia’ has been argued as useful in that ‘it unlocks services’. The numerous stories of people who’ve had their diagnosis changed from ‘dementia’ to ‘minimal cognitive impairment’, with disastrous personal reaction, are to some extent testament to this.

But IF it is the case that people have caused this effectively by living with a dementia better some serious scrutiny should be put into whether the medical profession in effect punishing people for living better with a chronic condition.

A concept, however, has emerged called the ‘affirmation model of disability’, which is described in this academic paper.

“Graby (2015) suggests that John Swain and Sally French’s (2000) ‘affirmation model of disability’ may be useful in taking this project forward, in which ‘disabled individuals assert a positive identity, not only in being disabled, but also being impaired. In affirming a positive identity of being impaired, disabled people are actively repudiating the dominant value of normality’ (Swain and French 2000, 578). The proposition from the neurodiversity movement is that we should reclaim and redefine ‘impairment’, in the same way as the first disability rights activists challenged the meaning of ‘disability’.”

This takes dementia, as a disability, into a new reframed arena of activism.

The same paper,

“It is our hope that building solidarity across experiences of marginalisation and disablement can move us beyond defining how we each individually deviate from the norm. At a time of increased psychiatrisation coupled with aggressive and devastating public spending cuts and government policies, we need to think collectively about how these processes affect us all.”

There are some people who find themselves, however, disabled by their diagnosis. This in policy is not drawn attention to for the correct fear of further exacerbating the stigma and prejudice surrounding dementia.

But dementia finds itself in the same and different place to other disabilities at the same time.

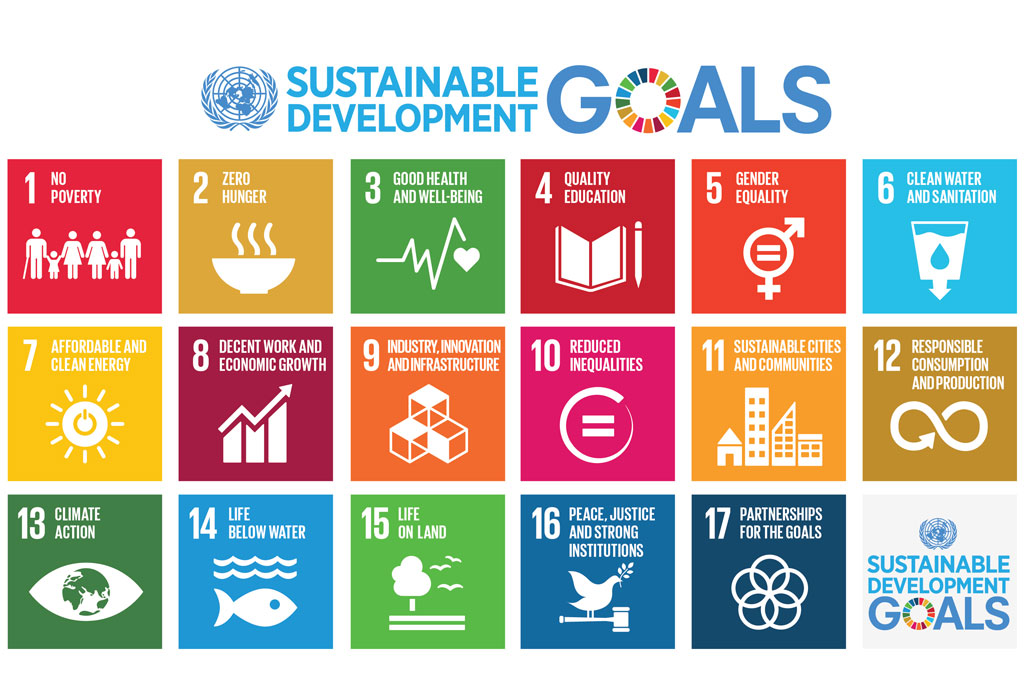

Dementia and other disabilities share the UN sustainable goals, similar to the UN millennium goals.

But on the hand people living with dementia around the world have experienced distress from austerity, due to the global financial crash of investment markets. In England, this has witnessed the collapse of the Independent Living Fund, while global investment goes into finding a pharmacological cure for dementia.

Being friendly to people around the world, living with dementia, was a well intended aim, for loneliness and social isolation frequently accompany the diagnosis of dementia (for the direct recipients of the diagnosis and carers as well).

However, it is clear that the 47 million people living with dementia have set their sights much higher.

The force awakens.

The commitment to living well with dementia is the latest expression of Disability Pride which has been around for a long time and takes many forms. By inventing the label of ‘neurotypicals’ for the rest of us, the Aspergers community has brilliantly asserted its right to difference.

Disability is a natural part of human experience. Dementia is a particularly good example because of its strong link with ageing. Society needs to find ways to overcome the barriers to our remaining active, respected and contributing citizens: people not patients