The term “challenging behaviours” was a very unfortunate import from the field of intellectual disabilities to dementia, necessitating the query “for whom behaviours are ‘challenging’?” Many people with dementia find behaviours of the medical profession ‘challenging’, being polite.

But a ‘good import’, arguably, would be the notion of “Portage”.

The name Portage comes from the town of Wisconsin, USA where the a home teaching scheme was developed in the 1970’s.

Portage is a home visiting educational service for pre-school children with additional needs. These may be learning difficulties, developmental delay or physical difficulties.

The “Portage Home Visitor” works with parents in their home because young children initially learn best in the security of their own environment, with the people who know them. In this way the best teaching programmes can be developed for every child.

Interesting ‘success stories’ exist elsewhere in the world too.

Founded in the Netherlands in 2006/07, Buurtzorg is a unique district nursing system which has garnered international acclaim for being entirely nurse-led and cost effective.

Prior to Buurtzorg, home care services in the Netherlands were fragmented with patients being cared for by multiple practitioners and providers.

Ongoing financial pressures within the health sector have led to home care providers cutting costs by employing a low-paid and poorly skilled workforce who were unable to properly care for patients with co-morbidities, leading to a decline in patient health and satisfaction. This is a problem which England shares too.

Indeed, a recent report last week from the International Longevity Centre discussed again the significance of co-morbidities in dementia Buurtzorg’s solution has to give its community district nurses far greater control over patient care – a factor which it attributes as key for its rapid growth.

There is huge interest as to whether ‘the Buurtzog model’ can be adapted for the English system.

Until recently, neither persons with dementia nor national dementia societies had used their right of access to UN Convention on Rights for People with Disabilities to which they are legally entitled defined by the scope of Article 1.

“Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

Prof Peter Mittler CBE, Advisor for Human Rights for Dementia Alliance International, writes:

“At the recent WHO Ministerial Conference on Dementia, Kate Swaffer [Chair of Dementia Alliance International] set the ball rolling at the opening session by including ‘Access to CRPD’ as one of DAI’s demands.”

In addition, a robust, human-rights based resolution submitted by Alzheimers Disease International on behalf of 38 national Alzheimers Associations was reflected in the first of the General Principles of the Call for Action by WHO Director Dr Margaret Wang.

It was remarked that an aspiration should be that “policies, plans, programmes, interventions and actions are sensitive to the needs, expectations and human rights of people living with dementia and their caregivers“.

The concept of ‘post-diagnostic support’ (soothing, but in reality weak words for England’s policy in dementia) needs to be re-configured as a rehabilitation pathway.

Essential to the re-framing of the whole discussion is getting rid of the idea that ‘post diagnostic support’ is a haphazard AFTER THOUGHT – and that the medical model is KING through the strategic placement of ‘diagnosis’. Sure, without the diagnosis, nothing further can happen, but the issue is that even with the diagnosis some people are experiencing next to nothing in care in England, and even if they experience some care it is fragmented and disjointed.

There is no better introduction into how the sequelae of the dementia diagnosis can be so positively destructive than Kate Swaffer’s own description of ‘prescribed disengagement™’ in a prominent journal here.

This pathway begins possibly even at the time of contemplation of the diagnosis with extensive support to after when the diagnosis has been given. At all times, the recipients of that diagnosis (including immediate closest) should be opportunities to ask questions and discuss ways in which care and/or support can be given.

Enablement should be the goal now.

Other jurisdictions, for example Queensland in Australia, have been outstanding in leading – see this report, for example, here.

Recent, rather limp words recently even seemed to miss out ‘caring well’ altogether – making English policy on this close a bit strange to put it mildly.

A ‘pathway’ is a somewhat cranky technocratic word, and could be considered entirely inappropriate in the context of an English government intent on cutting state provision of a ‘safety net’. But at best it might provide decision points which might be legitimately and reasonably expected at points in a personal integrated care and support plan following diagnosis.

The lack of national adoption of pathways, entirely due to entirely political reasons, and despite a plethora of evidence to prove pathways can promote health and wellbeing for patients with dementia and carers, has been noteworthy here in England, tragically.

Notwithstanding, a rehabilitation pathway would provide access to a wide range of specialists. These might include, for example, the following personnel, no one part of the ‘workforce’ being “more important” than others, promoting independence as part of an inclusive, accessible community for all.

People with dementia and those closest to them themselves have an important rôle to ply in co-designing pathways in genuine co-production, if they are working on an equal and reciprocal basis.

Specialist clinical nurses who can act from the point of diagnosis providing continuity of care are important are sufficient in themselves. They are especially helpful in applying palliative care principles. For too long, it has been dismissed that dementia is a terminal condition, thus denying many people with dementia equitable access to palliative approaches. Furthermore, it has been insufficiently addressed that people with dementia have a right to the highest standards of health from the NHS, regardless of setting.

These trained clinical nursing specialists are also extremely well placed to sort out issues arising from co-morbidities in health and illness, helping to head off avoidable acute admissions to hospital, or premature inappropriate transfer to residential care. Admiral nurses are also pivotal in helping coping strategies, essential in averting ‘crises’ in dementia care.

Other specialists might include:

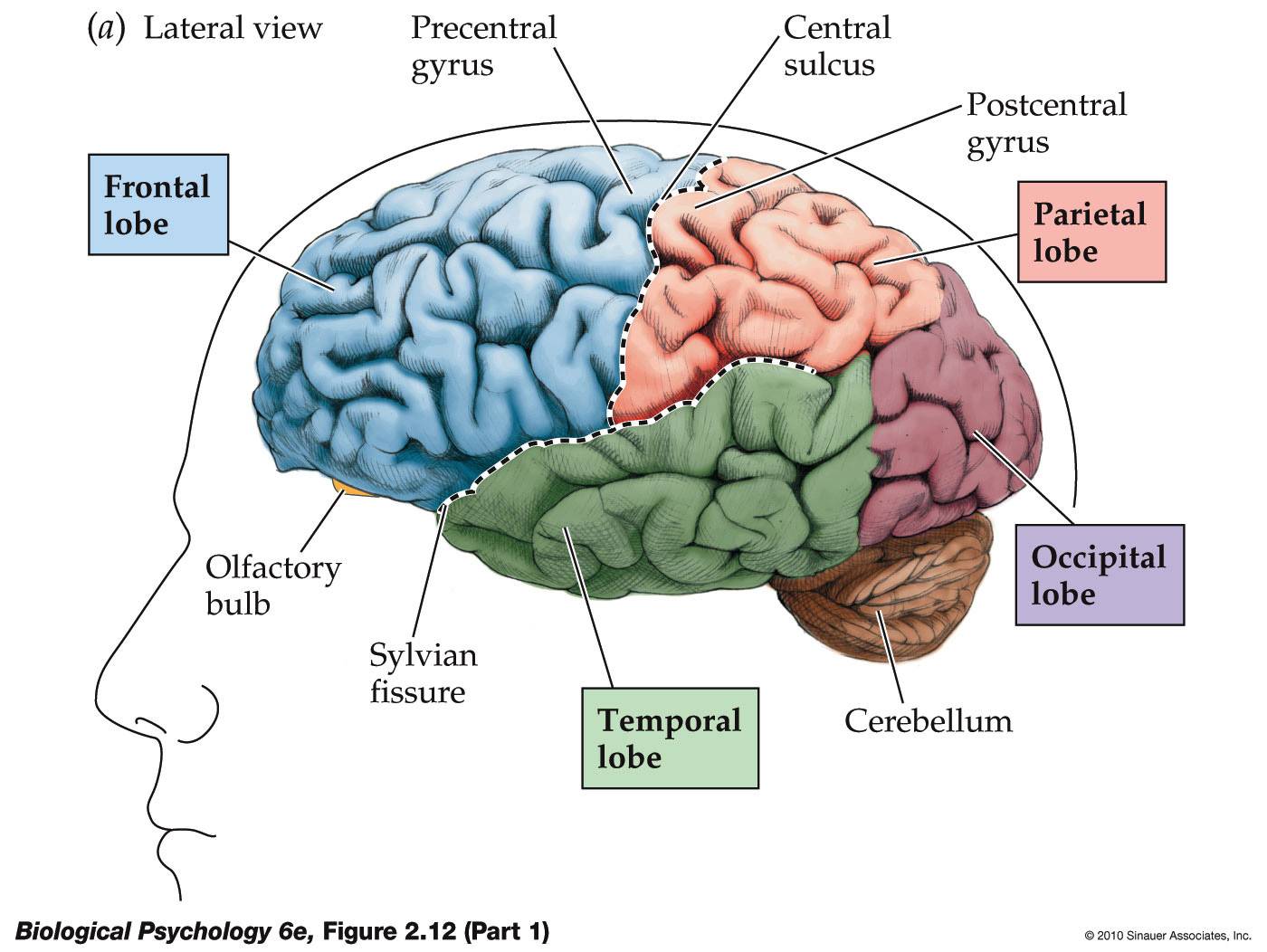

- Occupational therapists are pivotal, I feel; this rôle could include wider implications of he diagnosis and a discussion possible adaptations to the home and domestic appliances, and various forms of technology and innovations. A particular challenge, for example, might be to negotiate higher order problems in processing of the senses, including vision, as per posterior cortical atrophy.

- Physiotherapists to maintain mobility and promote physical exercise.

- Speech and language therapists to promote language and communication, especially important in Alzheimer’s disease and temporal forms of frontotemporal dementia, as well as to ensure safe swallowing following particular vascular events.

- Clinical neuropsychologists to advise on adjustment to diagnosis, improving and maintaining cognitive functioning, promoting thought diversity and an ‘assets based approach’ where people’s skills can be best utilised.

- Dieticians: a healthy diet is relevant in the progression of dementia, and especially so arguably for vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Also, latterly, particular attention has been given to optimising eating environments as part of the ‘healthy eating’ ethos.

- Social workers are much utilised in my opinion, and I should like to see a much wider rôle than in safeguarding or crises, though I think capacity building in the workforce of social workers with a specialist interest in mental health issues might be helpful. I think social work practitioners are vital in the promotion of wellbeing, in enabling and protecting people with dementia, and provide access to community resources perhaps including personal budgets for some,

- Pharmacists. Many medications can worsen cognitive symptoms potentially and act as risk to physical health indeed, and inappropriate polypharmacy needs to be reviewed by specialists in pharmacy.

Certainly medical professionals in primary and secondary care are vital where another plank of integration is needed, to ensure people with dementia and their closest genuinely do get the right care in the right time at the right place. I have no doubt primary care, with their wide experience of medicine, and upholding a proactive stance too, would be vital in community based rehabilitation, including general practitioners. But the current service issues in resources for, recruitment to, excessive regulation of, and access to general practitioners in England cannot be ignored.

The UN 2016-2030 Sustainable Development Goals were launched with a commitment to “Leave No One Behind”, a similar theme having been ‘no decision about us without us’. I have a concern that the poorly named “dementia friendly communities”, being aimed at being politically inoffensive by the chief cheerleaders in England, and being so cost neutral, does not do enough to resolve social inequalities in reality.

We know this is a danger, say, for housing. But worldwide extrapolation of inequity would be disaster, particularly when we consider the number of people thought to be living with dementia in low and middle income countries around the world.

All too easily ‘dementia friendly communities’ can become a strapline as a sticking plaster for cuts elsewhere in the Big Society, to secure a quickie competitive advantage in marketing – this is indeed addressed in this briefing from March 2015 here:

“There have been concerns that the target created incentives for governments to focus on‘low hanging fruit’ rather than those most in need.”

As a consequence of sustained advocacy, persons with disabilities are now clearly included in the 17 SDGs and 169 implementation indicators. Although the needs of older persons are recognised, persons with dementia are in grave risk of being overlooked.

It is likely that, if Big Pharma are successful in producing orphan drugs capable of being regulated and distributed, there will be an inequity regarding domestic recommendations about making these drugs available. The ‘economics of rescue’ doctrine means that there should be no stone unturned in providing medications in palliative care; but NICE will have other views on the greatest benefit for the largest number of people in their econometric ullitarian cost-benefit analysis.

It is indeed likely that persons with dementia in Low and Middle Income Countries should be able to benefit from the long established WHO Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Programme described here.

“Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) was initiated by WHO following the Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978 in an effort to enhance the quality of life for people with disabilities and their families; meet their basic needs; and ensure their inclusion and participation. While initially a strategy to increase access to rehabilitation services in resource-constrained settings, CBR is now a multisectoral approach working to improve the equalization of opportunities and social inclusion of people with disabilities while combating the perpetual cycle of poverty and disability. CBR is implemented through the combined efforts of people with disabilities, their families and communities, and relevant government and non-government health, education, vocational, social and other services.”

As a clear example as what could be achieved by engaging trained professionals too into English dementia policy, the Royal College of Physicians of London have been leaders too.

See this interesting case study:

“This Future Hospital Programme case study describes how the Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust is fulfilling their aim of achieving stroke rehabilitation 7 days a week in both the Stroke Rehabilitation Unit and surrounding areas.”

Stroke care, like cancer care, is in a different place to dementia.

And we know why. The only hope in English policy appears to be some chosen ones selectively adding fertiliser to a few flowers blooming when the entire garden had actually been devoid of being watered for several years. And this needs fixing the gardener.

Unfortunately, people who are less skilled – but who are ‘advising’ or ‘supporting’ – might possibly insufficient alone to service needs of people living with dementia and carers, even if they meet the needs of certain charities, but they do serve a useful function in service provision. Quality is essential for enablement.

–

Please come to see my talk in the policy stream of the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference this week in Budapest.