“Citizens have become consumers with status proportional to purchasing power, and former public spaces have been enclosed and transformed into private malls for shopping as recreation or “therapy.” Step by step, private companies, dedicated to enriching their owners, take over the core functions of the state. This process, which has profound implications for health policy, is promoted by politicians proclaiming an “ideology” of shrinking the state to the absolute minimum. These politicians envisage replacing almost all public service provision through outsourcing and other forms of privatisation such as “right to provide” management buyouts. This ambition extends far beyond health and social care, reaching even to policing and the armed forces.”

And so write Jennifer Mindell, Lucy Reynolds and Martin McKee recently about ‘corporate capture’ in the British Medical Journal.

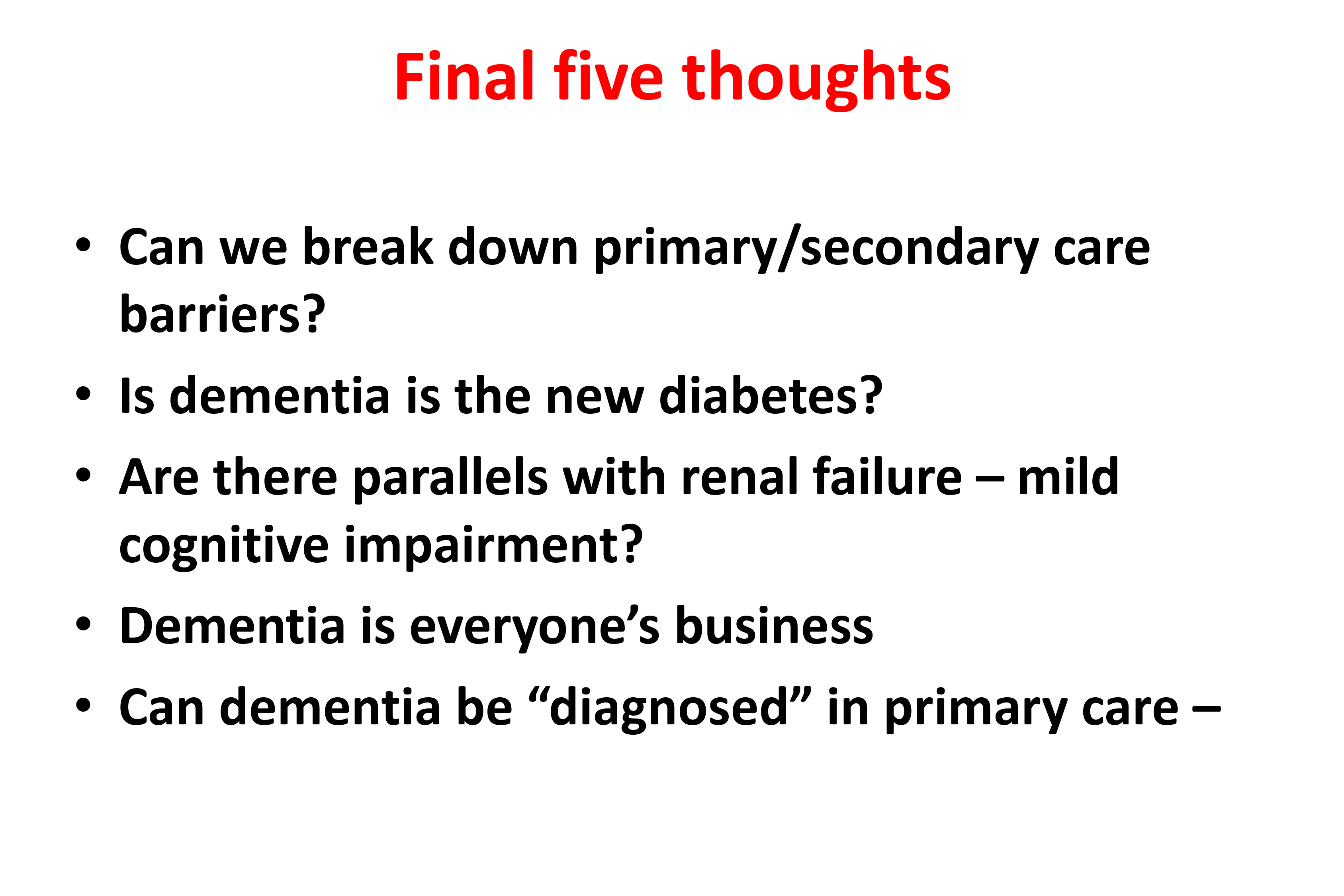

Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead on dementia, recently concluded a presentation on the clinical network for London with the following slide:

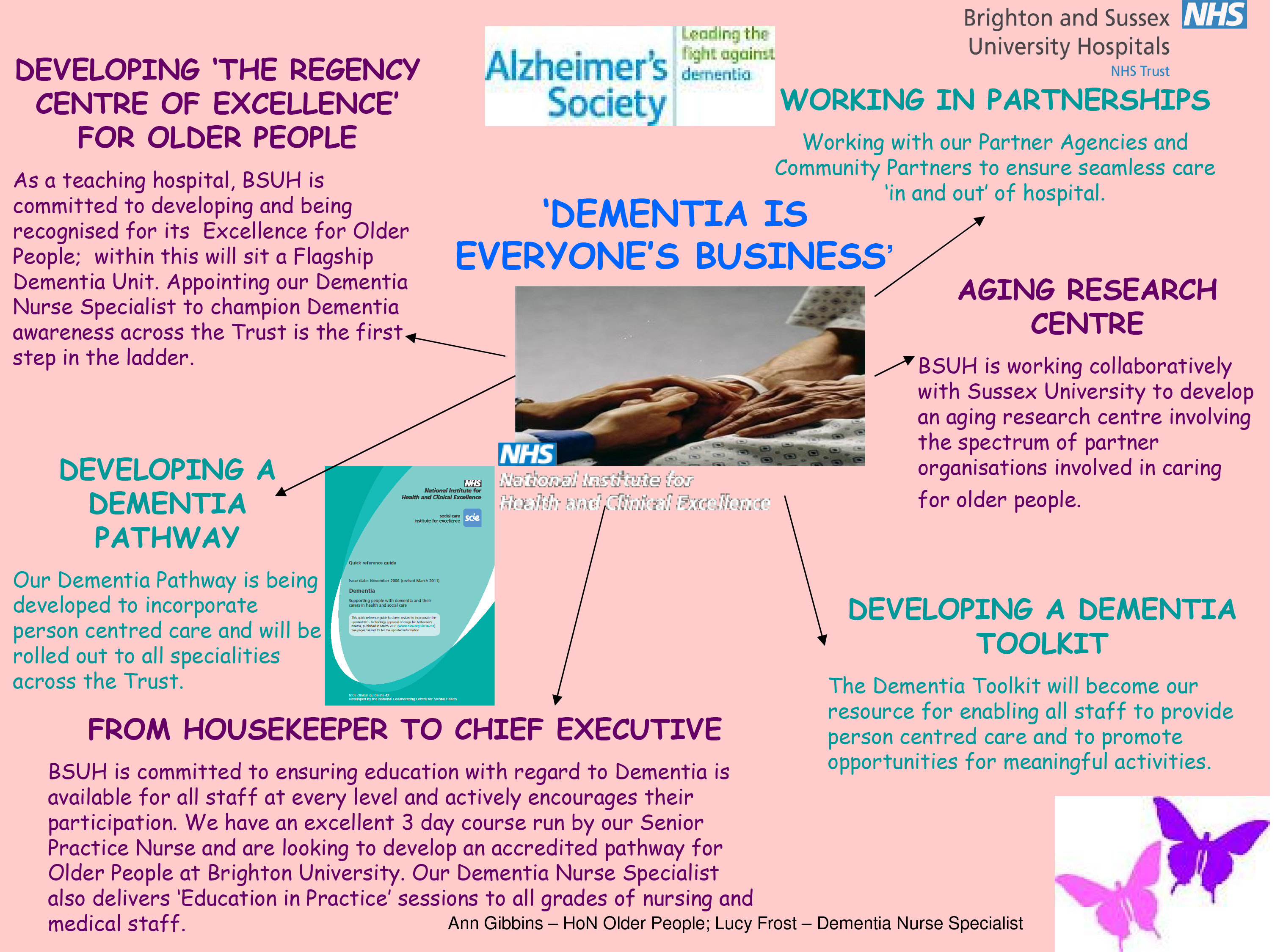

Alistair clearly does not mean ‘Dementia is everyone’s business’ in the “corporate capture” sense. Instead, he is presumably drawing attention to initiatives such as Brighton and Sussex Medical School’s initiative to promote dementia awareness at all levels of an organisation (and society).

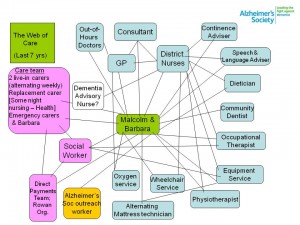

The comparison with diabetes is for me interesting in that I think of living well with diabetes, post diagnosis, as conceptually similar to living well with dementia, in the sense that living well with a long term condition is a way of life. And with good control, it’s possible for some people to avoid hospital, becoming patients, when care in the community would be preferred for a number of clinical reasons. Where I feel the comparison falls flat is that I do not think that it is possible to measure outcomes for living well with dementia easily. Sure, I have writen on metrics used to measure living well with dementia, drawing on the work of Sube Banerjee, Alistair’s predecessor. It might be possible to correlate good control with a blood test value such as the HBA1c, and it steers the reward mechanism of the NHS for rewarding clinicians for failure of management (e.g. laser treatment in the eye, foot amputation, renal dialysis), but the comparison needs some clinical expertise to be pulled off properly. The issue of breaking down ‘barriers’ between primary and secondary care is an urgent issue, and ‘whole person care’ or ‘integrated care’ may or may not help to facilitate that. But a future government must not get too enmeshed in sloganising if it means forgetting basic requirements of foot soldiers on the ground, such as specialist dementia nurses including Dementia UK’s ‘Admiral nurses’.

But the question of who gives the correct diagnosis of dementia, or even verifies it, won’t go away.

Having done Dementia Friends myself, a Public Health England the Alzheimer’s Society joint initiative, I feel the initiative is extremely well executed from an operational level. I think it’s pushing it for a member of the public to think that an old and doddering lady crossing the lady might have dementia and requires help, as medicalising ageing into dementia is a dangerous route to take. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. Public Health England are planning to undertake an evaluation of the Dementia Friends Campaign launched on 7 May 2014, which will include tracking data and prevention message testing.

There are a number of important clinical points here. There are crucial questions as to whether persons themselves with a possible diagnosis, friends and/or families themselves want a diagnosis of dementia. A diagnosis of dementia in anyone’s book is a life-changing event. The concerns of the medical profession have been effectively rehearsed. Notwithstanding, the ambition that, by 2015, two thirds of the estimated number of people with dementia should have a diagnosis, with appropriate post diagnostic support has been agreed with NHS England. To support GPs and other primary care staff, a Dementia Roadmap web-based tool has been commissioned by the Department of Health from the Royal College of General Practitioners. The roadmap has now been officially launched, and will provide a framework that local areas can use to provide local information about dementia from health, social care and the third sector to assist primary care staff to more effectively support patients, families and carers from the time of diagnosis and beyond. Feedback from relevant stakeholders will be most interesting.

People with dementia need to be followed up across a period of time for a diagnosis of dementia to be reliably made, and ‘in the right hands’, i.e. of a specialist dementia service. Whilst NHS England are working with those areas with the longest waits, with the aim of ensuring that anyone with suspected dementia will not have an excessive wait for a timely assessment, there has to be monitoring of who does that timely assessment and whether it produces an accurate result. At an extreme example, clinical diagnoses of rarer dementias, particularly younger onset, can only be done effectively by senior physicians with reference to two clinical histories, two clinical examinations, neuroimaging (e.g. CT, MRI, or even fMRI or SPECT), lumbar puncture/cerebrospinal fluid (if not contraindicated), cognitive psychology, EEG, or even – extremely rarely – a brain biopsy. But this would be to propose an Aunt Sally argument – many possible cases of dementia can be tackled by primary care with appropriate testing perhaps in the future, and certainly adequate resources will need to be put into primary care for training of the workforce. Or else, it is literally a ‘something for nothing’ approach. Some people have ‘mild cognitive impairment’ instead, and will never progress to dementia.There are 149,186 dementia friends currently. This number is rapidly increasing. The goal is one million.Furthermore, there are many people given a diagnosis of dementia while alive who never have it post mortem. And the diagnosis can only be definitively made post mortem. Seth Love’s brilliant research (and he is an ‘Ambassador’ to the Alzheimer’s BRACE charity) is a testament to this. Anyway, NHS England and the Department of Health are working with the Royal College of Psychiatrists to encourage more Memory Services to become accredited.

And when is screening not officially screening? This continues to require definition in England’s policy. The original Wilson and Jungner (1968) principles have appear to have become muffled in translation. The CQUIN has led to over 4,000 referrals a month, but this will only contribute to improving diagnosis rates for dementia if this is not producing a tidal wave of false positives. For quarter 3 2013/14, 83% of admitted patients were initially assessed for potential dementia. Of those assessed and found as potentially having dementia, 89% were further assessed. And of those diagnosed as potentially having dementia, 86% were referred on to specialist services. But we do need the final figure. This policy plank for me will also go back to the issue of whether policy is putting sufficient resources into the diagnostic process and beyond. Stories of people being landed with a diagnosis out of nowhere and given not much further information than an information pack are all too common. A well designed system would have counselling before the diagnosis, during the diagnosis, and after the diagnosis.

Ideally, an appointed advisor would then see to continuity of care, allowing persons with dementia to be able to feel confident about telling their diagnosis to friends and/or family. The advisor would ideally then give impartial advice on social determinants of health, such as housing or education. Policy may be slowly moving in this direction. In April 2014 NHS England published a new Dementia Directed Enhanced Service (DES) for take up by GPs to reward practices for facilitating timely diagnosis and support for people with dementia. Patients who have a diagnosis of dementia will be offered an extended appointment to develop a care plan. The care planning discussion will focus on their physical and mental health and social needs, which will include referral and signposting to local support services. From 10 signatories in March 2012, to date, there are now 173 organisations representing nearly 3,000 care services committed to delivering high quality, personalised care to people with dementia and their carers.

But all this requires money and skill. There is no quick fix.

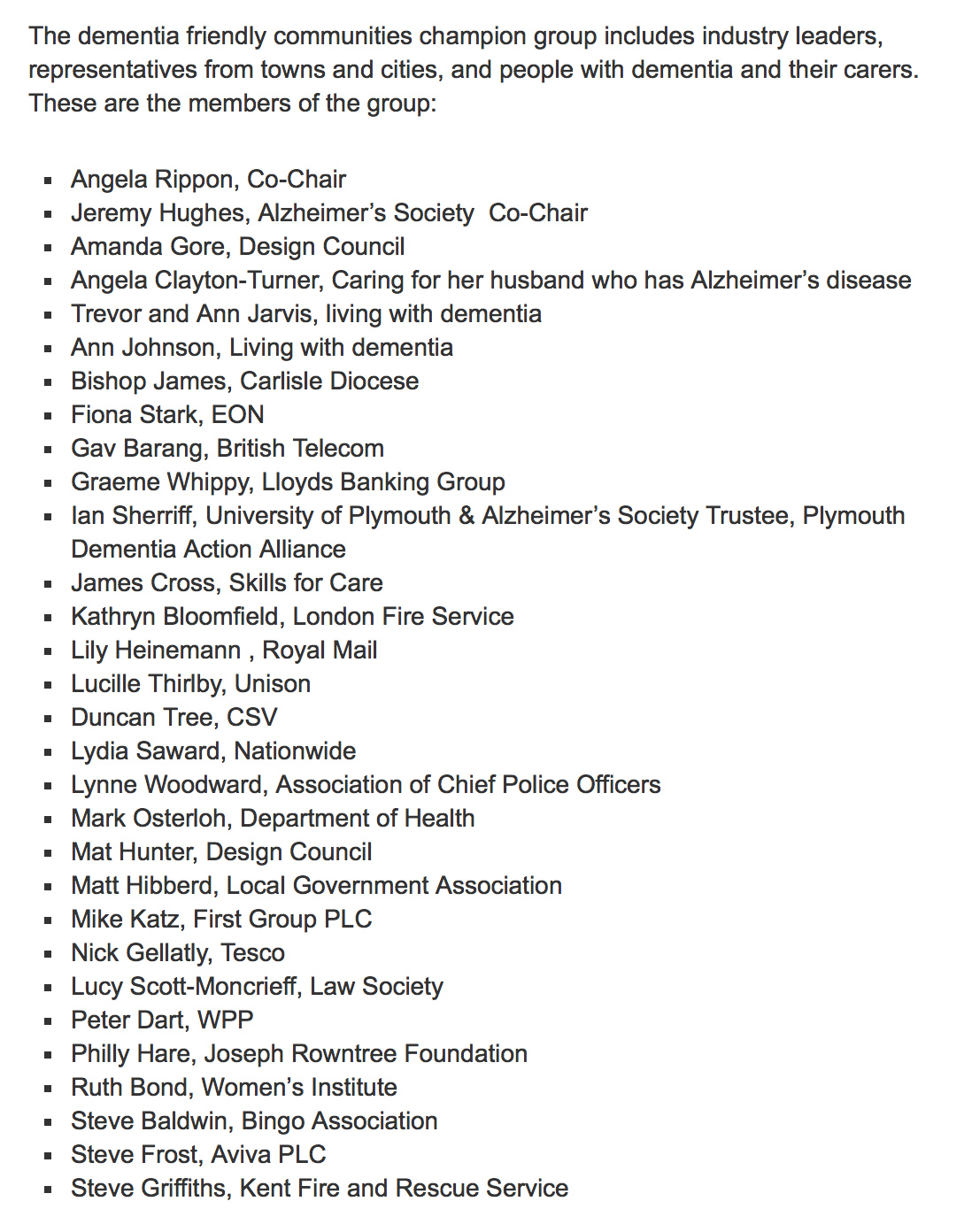

The areas of action for the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge are: dementia friendly communities, health and care and improving research.

It happens to fit very nicely with the Big Society and the ‘Nudge’ narrative of the current government. But it sits uneasy with the idea that it is in fact a manifestation of a small state which bears little responsibility apart from overseeing at an arm’s length a free market. The critical test is whether this policy plank might have improved NHS care. 42 NHS and 74 Social Care National pilot schemes were approved in June 2013 as national pilots. Most of the projects have now been completed, and they will be evaluated by a team of researchers at Loughborough University over the coming months. The evaluation will provide knowledge and evidence about those aspects of the physical care environment which can be used to provide improved care provision for people with dementia, their families and carers. But the policy has had some very exciting successes: for example the ‘Sporting Memories Network’, an approach based on the neural re-activation of sporting autobiographical memories, recently scooped top prize for national initiative in the Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Friendly Communities Awards 2014.

And meanwhile, the care system in England is on its knees. Stories of drastic underfunding of the care system are extremely common now. An army of millions of unpaid family carers are left propping up a system which barely works. There appears to be little interest in guiding these people, with psychological, financial and/or legal burdens of their own, to reassure them that all their hard work is delivering an extraordinary level of person-centred care.

But this for me was an inevitable consequence of ‘corporate capture’. The G8 World Dementia Council does not have any representatives of people with dementia or carers.

That is why ‘Living well with dementia’ is an important research strand, and hopefully one which Prof Martin Rossor and colleagues at NIHR for dementia research will give due attention to in due course. But all too readily research into innovations, ambient assisted living, design of the ward, dementia friendly communities, assistive technology, and advocacy play second fiddle to the endless song of Big Pharma, touting how a ‘cure’ for dementia is just around the corner. Yet again.

So what’s the solution?

The answer lies, I feel, in particularly what happens in the next year and beyond.

The Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia was developed as a successor to the National Dementia Strategy, with the challenge of delivering major improvements in dementia care, support and research. It runs until March 2015. Preparatory work to produce a successor to the Challenge from the Department of Health (of England) is now underway in order that all the stakeholders can fully understand progress so far and identify those areas where more needs to be done. The Department of Health have therefore commissioned an independent assessment of progress on dementia since 2009.

There are a number of other important pieces of work that are underway, which will provide information and evidence about progress and gaps. For example, according to the Department of Health, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia chaired by The Baroness Sally Greengross OBE are producing a report focused on the National Dementia Strategy, and the Alzheimer’s Society has commissioned Deloitte to assess progress and in the autumn will be publishing new prevalence data. Indeed the corporate entity known as Deloitte Access Australia (a different set of management consultants in the private sector) produced in September 2011 a report on prevalence of dementia estimates in Australia. Deloitte themselves have an impressive, varied output regarding dementia. But of course they are not interested in dementia solely. “Deloitte” is the brand under which tens of thousands of dedicated professionals in independent firms throughout the world collaborate to provide audit, consulting, financial advisory, risk management, tax, and related services to select clients.

But also it appears that the Alzheimer’s Society, working with NHS England, has commissioned the London School of Economics to undertake a review into the accuracy of dementia prevalence data. The updated data is expected to be published in Autumn 2014. Apparently, once all this work has been concluded a decision will be made on the focus and aims of the successor to the PM’s challenge.

The current Coalition government has been much criticised in parts of the non-mainstream media for the representation of corporate private interests in the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

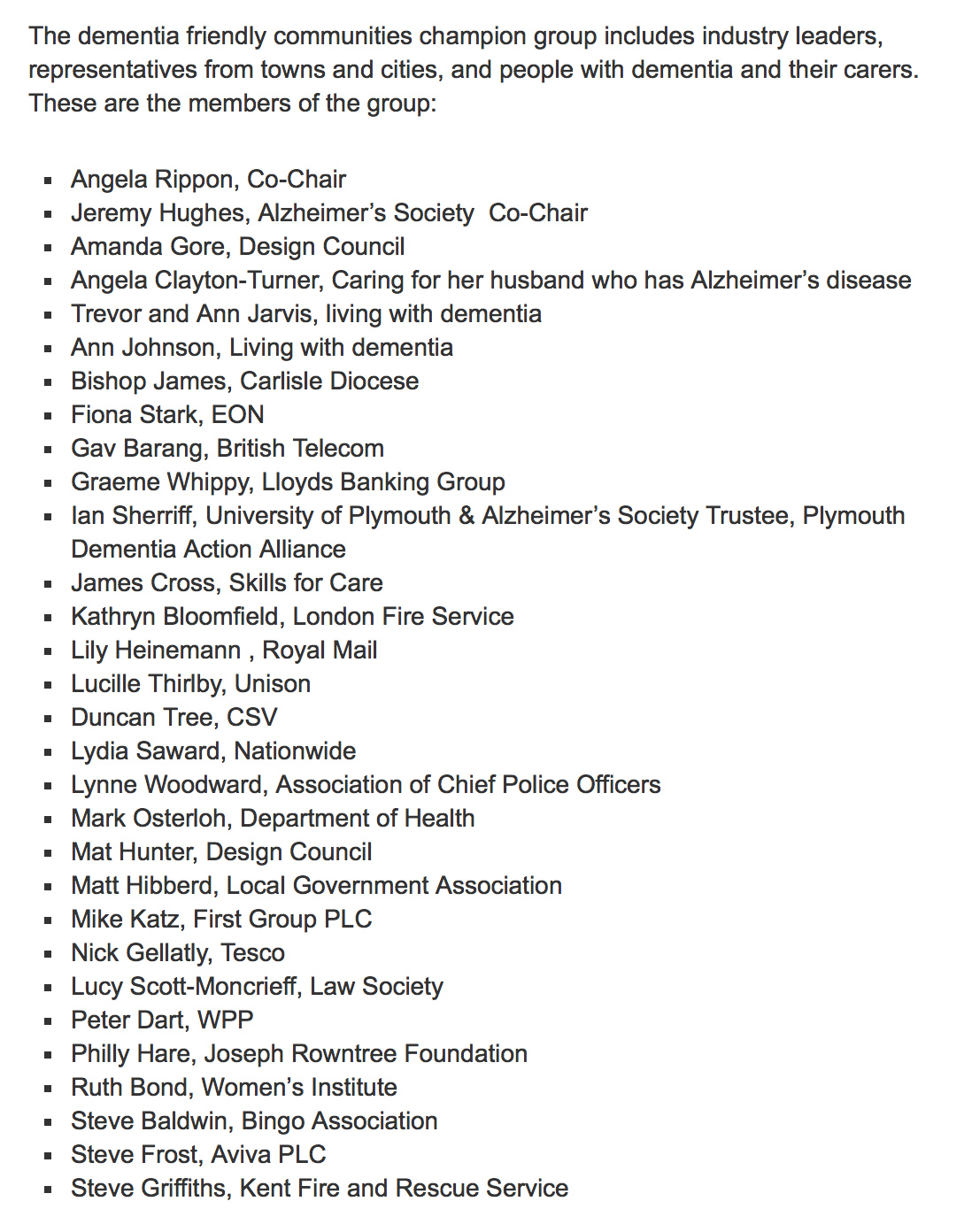

I believe people who are interested in dementia, including persons with dementia, caseworkers and academics, should make their opinions known to the APPG in a structured articulate way in time. I think not much will be achieved through the pages of the medical newspapers. And only time will tell whether the new dementia strategy will emerge in time before the next general election in England, to be held on May 7th 2015. However, even the most ardent critics will ultimately. The present Government should be congratulated for having made such a massive effort in educating the country about dementia, which is a necessary first step towards overcoming stigma and discrimination. The Alzheimer’s Society has impressively delivered its part of it, it appears, but future policy will benefit from much more ‘aggressive inclusion’ of other larger stakeholders (e.g. the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Dementia UK) and smaller stakeholders.

And special thanks to Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead for dementia, a Chair at Manchester, and much more.

It could be a case of: all change please. But a huge amount has been done.