Background

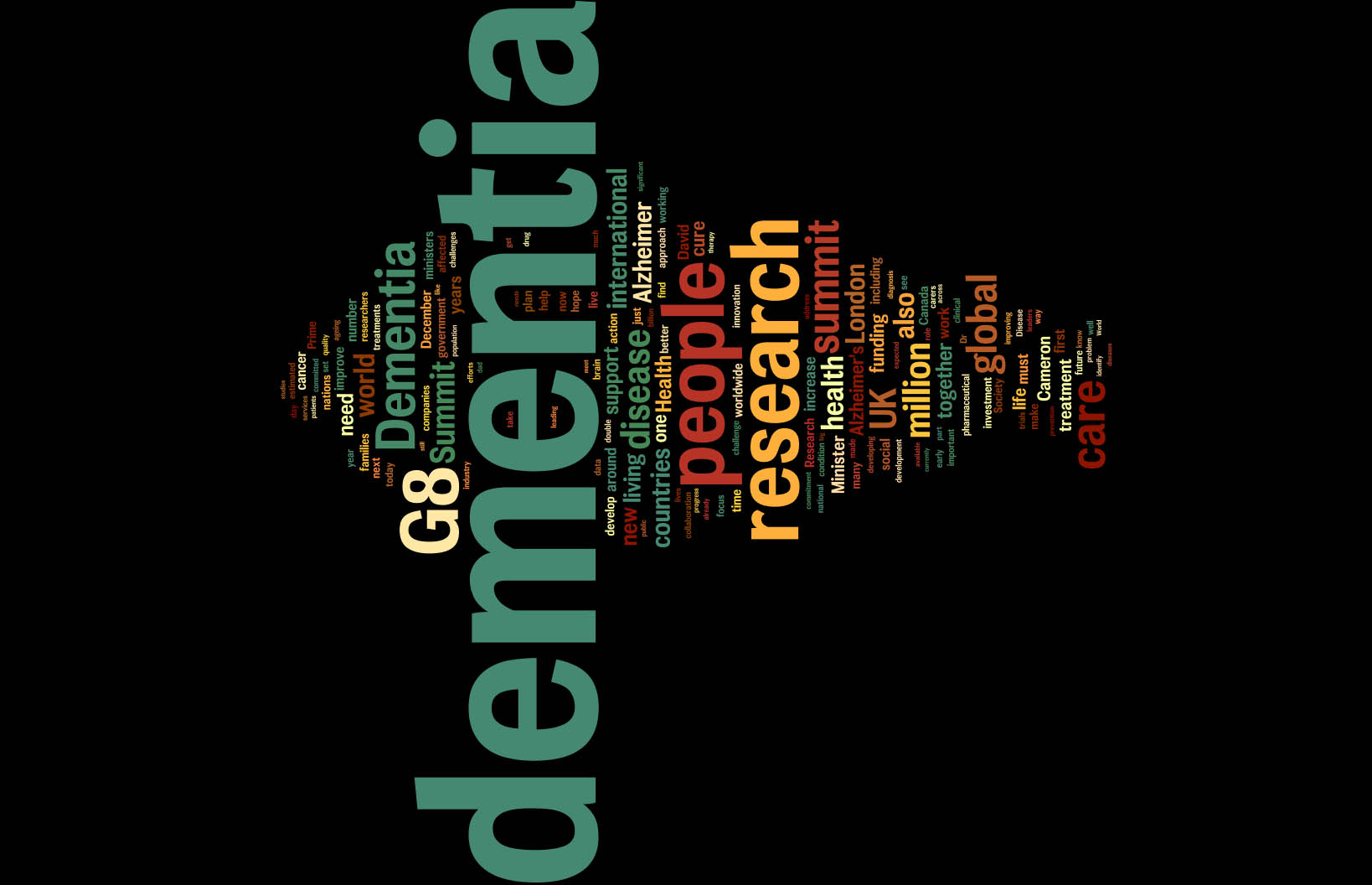

The G8 summit on dementia was much promoted ‘to put dementia on top of the world agenda’.

It is described in detail on the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” website.

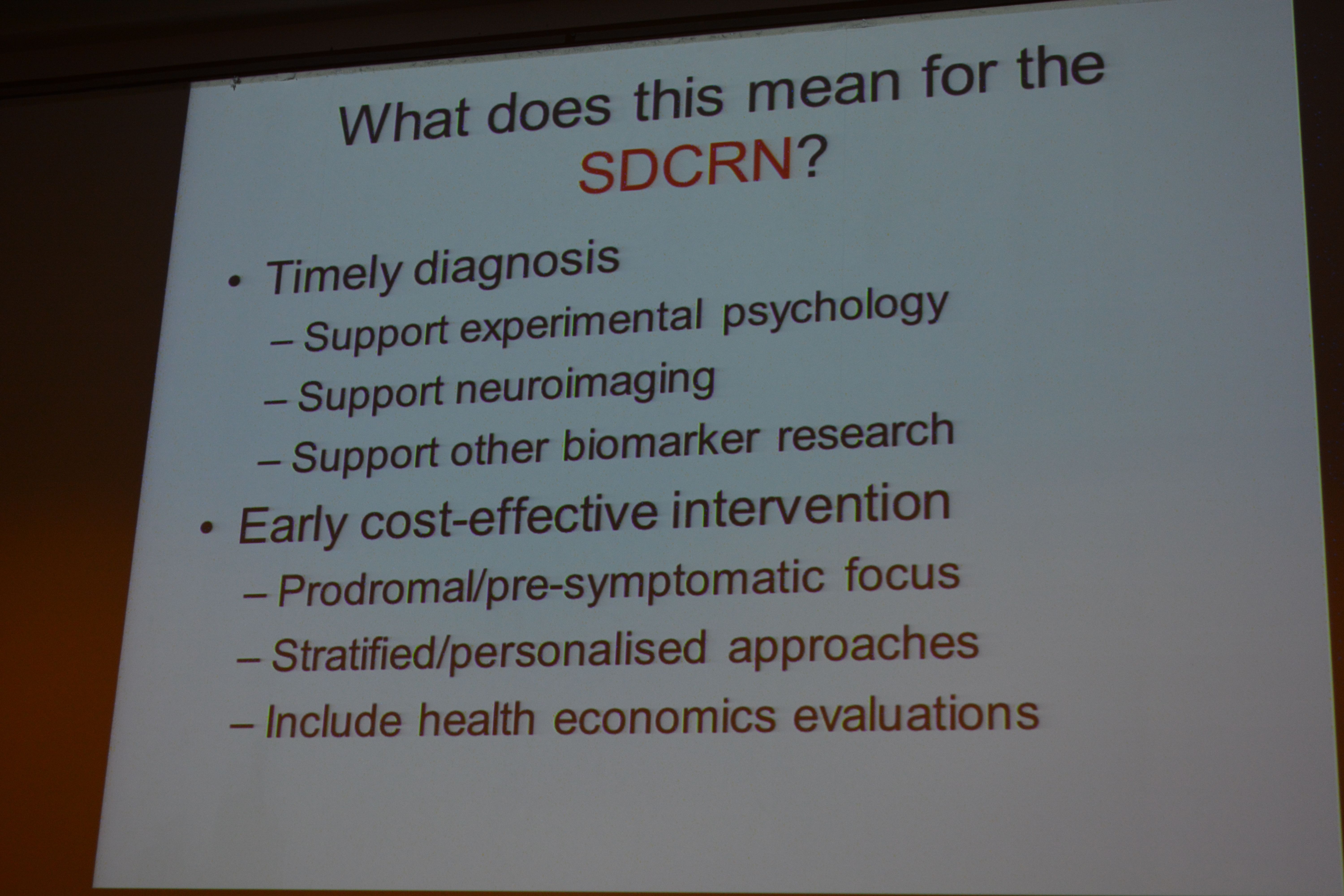

I went only last Monday to Glasgow to the SDCRN conference retrospective on the G8 dementia. It was a sort-of debrief for people in the research community about what we could perhaps come to expect. And what we’d come to expect, just in case any of us had thought we’d dreamt is was the idea of identifying dementia before it had happened or just beginning to happen and stopping it in its tracks then and there with drugs.

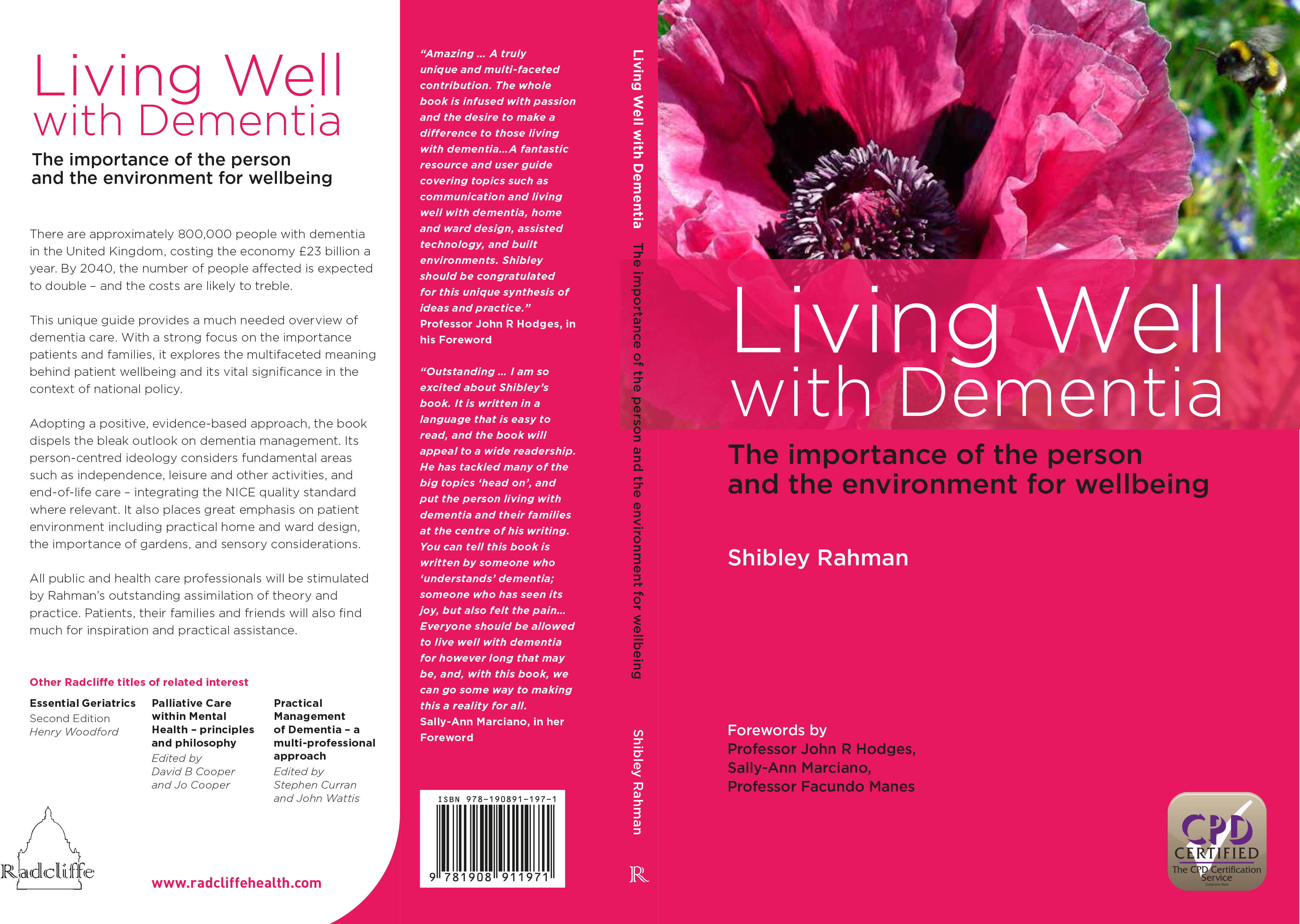

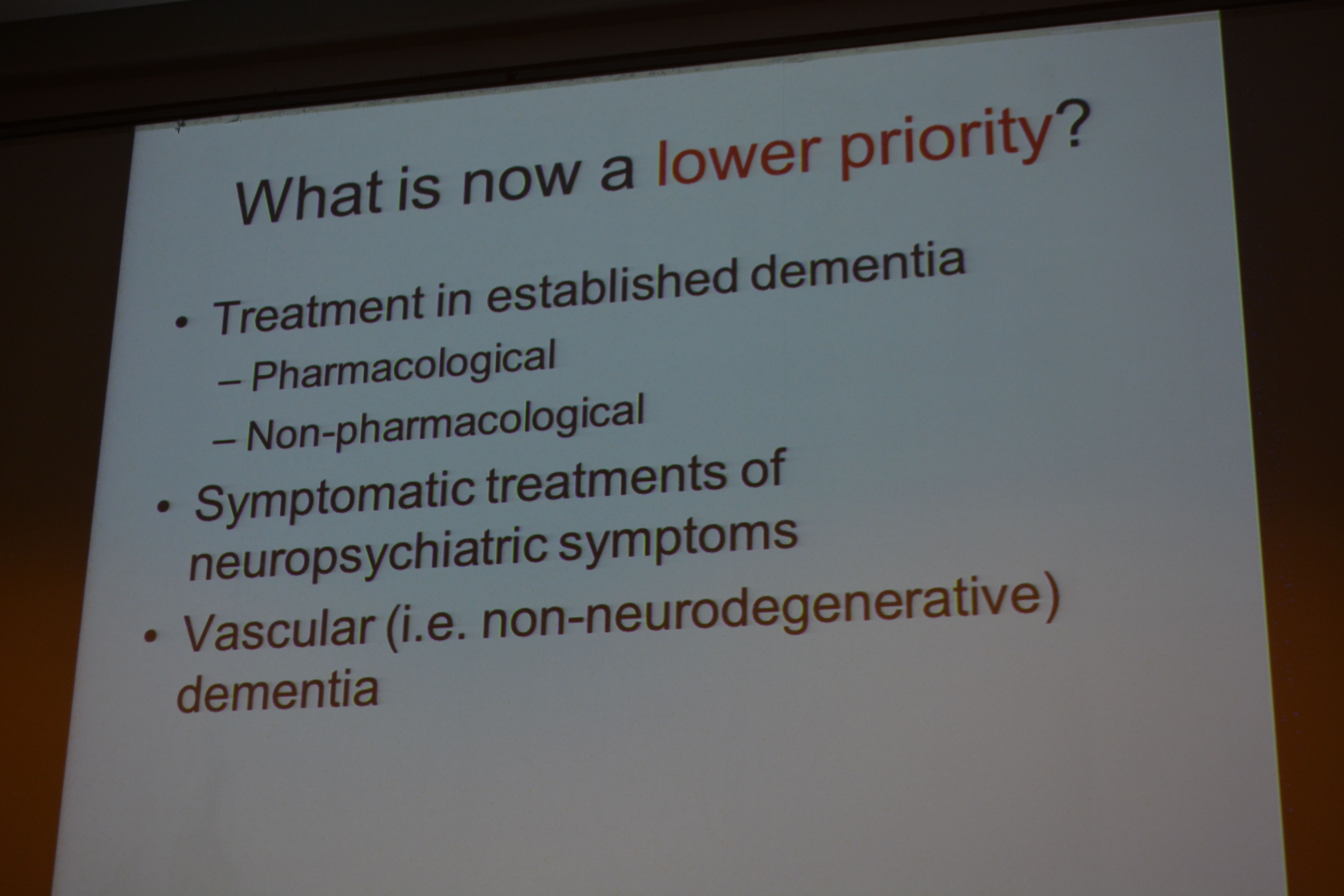

This is of course a laudable aim, but an agenda utterly driven by the pharmaceutical industry. My philosophy (not mine uniquely) “Living well in dementia” is called “non-pharmacological interventions” to denote a sense of inferiority under such a construct.

Aim

There has never been a media report on people’s views about the G8 dementia summit.

There has never been an analysis of the messaging of this summit in the scientific press, to my knowledge.

This study was conducted as a preliminary exploratory study into the language used in a random sample of 75 articles in the English language.

Methods

I completed a survey of reactions to the G8 dementia summit held last year in December 2013. I recruited people off my Twitter accounts @legalaware and @dementia_2014, and there were 96 respondents. Responses to individual items varied from 63 to 96.

I used ‘SurveyMonkey’ to carry out this survey. With ‘SurveyMonkey’, you cannot complete the survey more than once.

(I have also already collected 19 detailed questionnaire responses from Clydebank which I intend to write up for the Alzheimer Europe conference later this year, also in Glasgow. And also six people living with dementia also responded; and I’ll analyse these replies separately. I reminded myself by looking at the programme of the summit again what the key topics for discussion were – drugs, drug development and data sharing, with a sop to innovations and provision of high quality of information. It is perhaps staggering that there has been no detailed analysis of who benefited from the G8 dementia, but given the nature of this event, the media reportage and the events of my survey, this retrospectively is not at all surprising to me.)

Exclusions

Persons with dementia were directed to a different link (of the same survey.)

Results

The results encompass a number of issues about media coverage, the relative balance of cure vs care, and who benefited.

Media coverage

Overall, most people had not caught any of the news coverage on the TV (56%) or radio (55%). But most had caught the coverage on the internet, for example Facebook or Twitter (66%). 87% of people said they’d missed the live webinar. It was possible to answer my survey without having caught of any of the G8 seminar, however.

So what did people get out of it and what did they expect? Most people did not think the summit was a “game changer” (53% compared to 16%; with the rest saying ‘don’t know’), although the vast majority thought the subject matter was significant (82%) (n = 90).

Therefore, unsurprisingly, a majority considered the response against dementia to be an opportunity for policy experts to produce a meaningful solution (58%). However, it’s interesting that 24% said they didn’t know (with a n = 90 overall.)

In summary, they had high hopes but few thought it was a good use of a valuable opportunity to talk about dementia.

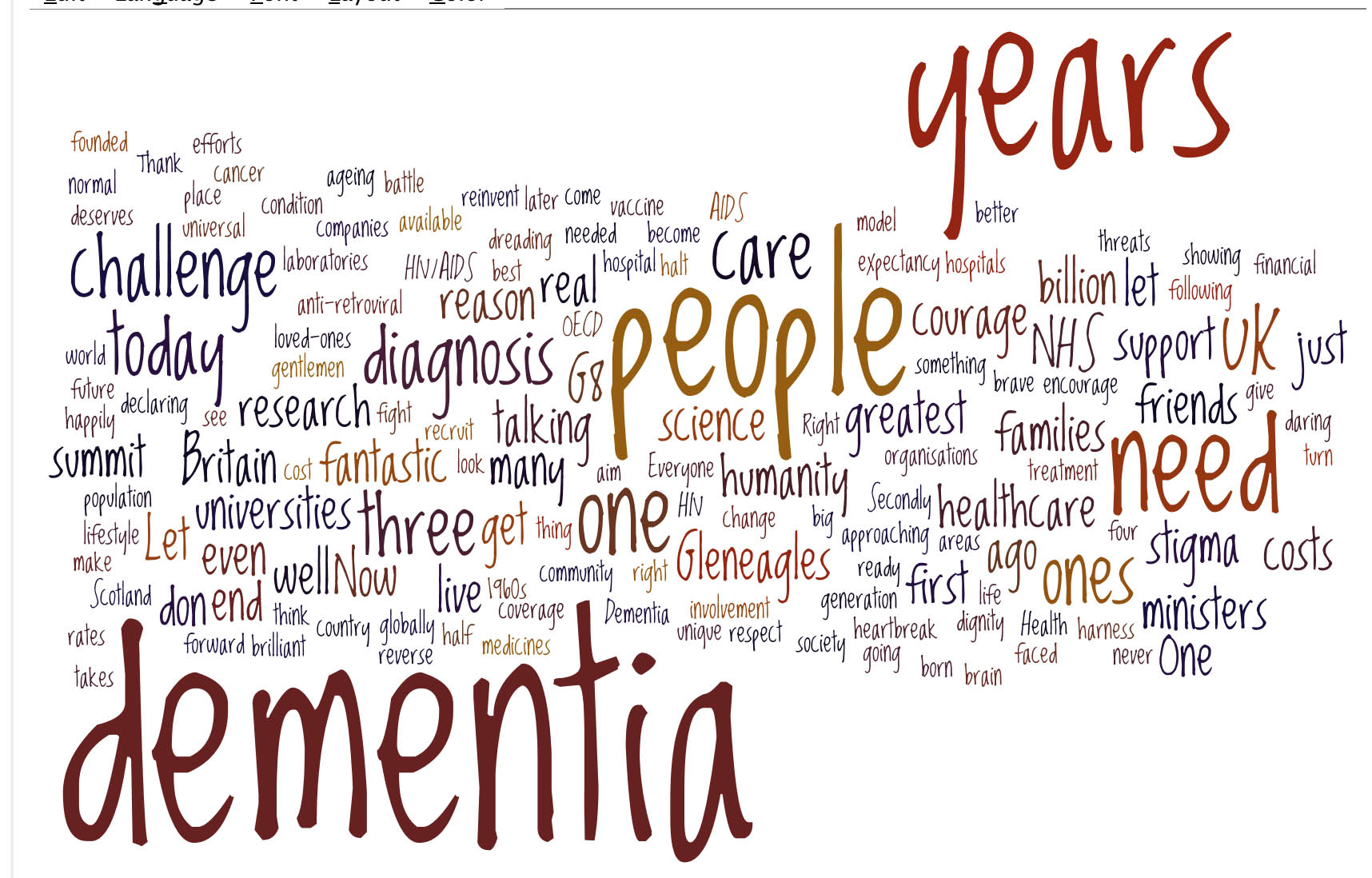

Many of us in the academic community had been struck in Glasgow at the sheer “terror” in the language used in referring to dementia. A large part of the media seemed to go for a remorseless ‘shock doctrine’ approach. Prof Richard Ashcroft, a medical law and bioethics expert from Queen Mary and Westfield College, University of London, wrote a very elegant piece about this, and his personal reaction, in the Guardian newspaper.

In terms of language, the respondents were consistent in not viewing the response against dementia as a “fight” (61%), a “war” (84%), a “battle” (72%) or an “epidemic” (70%) (n ranging from 83 to 86). 56% of people considered it unreasonable to speak of “turning the tide against dementia”. In terms of personal reactions, 82% considered themselves not to be “shocked” by dementia.

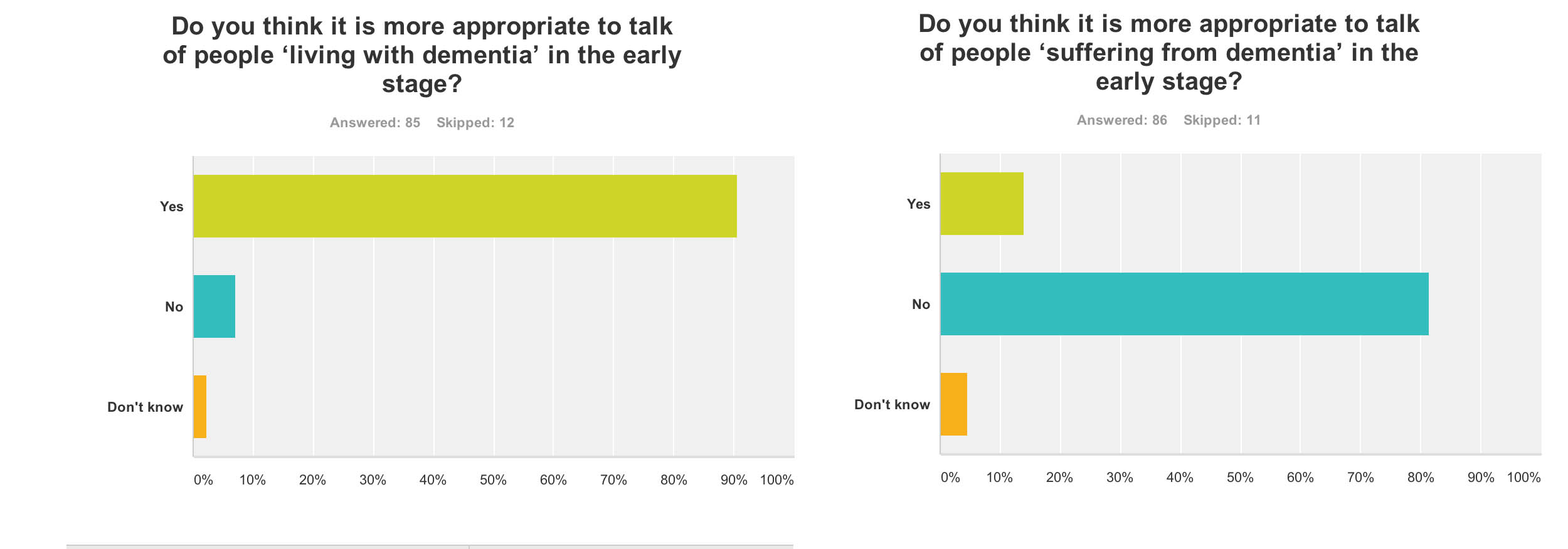

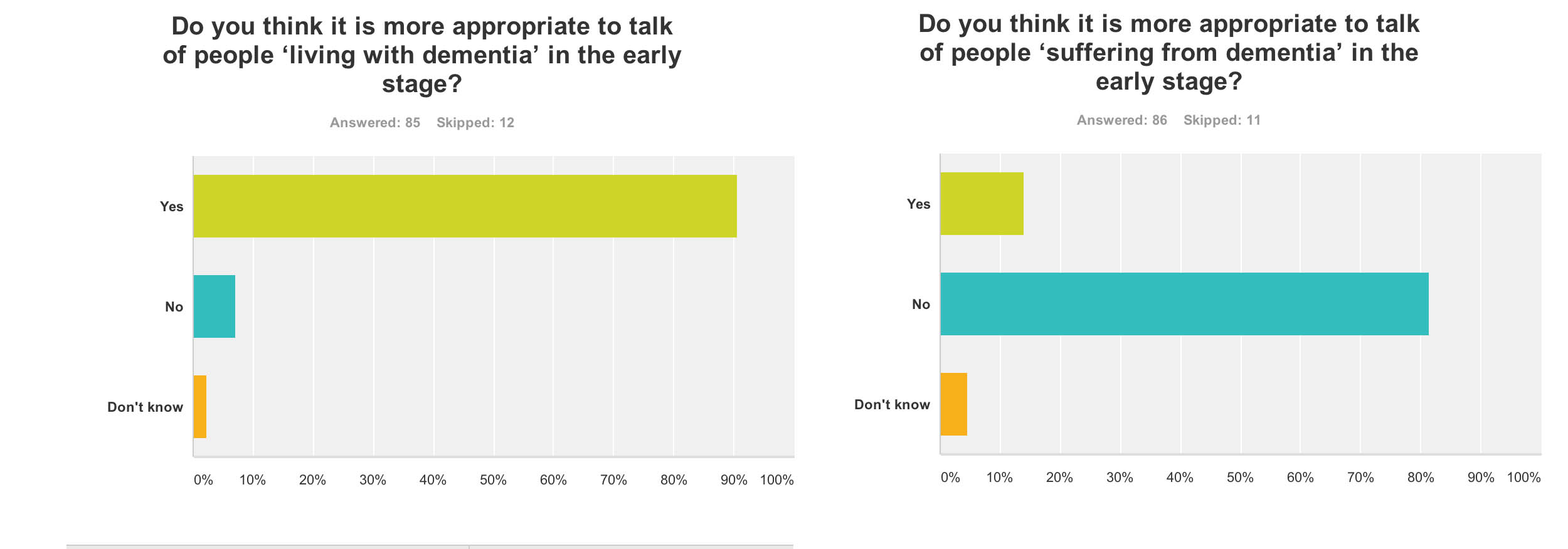

91% of people thought it was appropriate to talk of ‘living with dementia’ in the early stage (n = 85), but 82% of people did not think it was more appropriate to talk of people ‘suffering from dementia’ at this early stage (n = 86). In retrospect, I should’ve asked whether the appropriate phase was ‘living well with dementia’, so I suppose nearly 91% endorsing ‘living with dementia’ at all is not surprising. I have previously written about the use of the word “suffering”, as it is so commonly used in newspaper titles of articles of dementia here, though I readily concede it is a very real and complex issue.

The opportunity presented by the G8 dementia summit: cure vs care

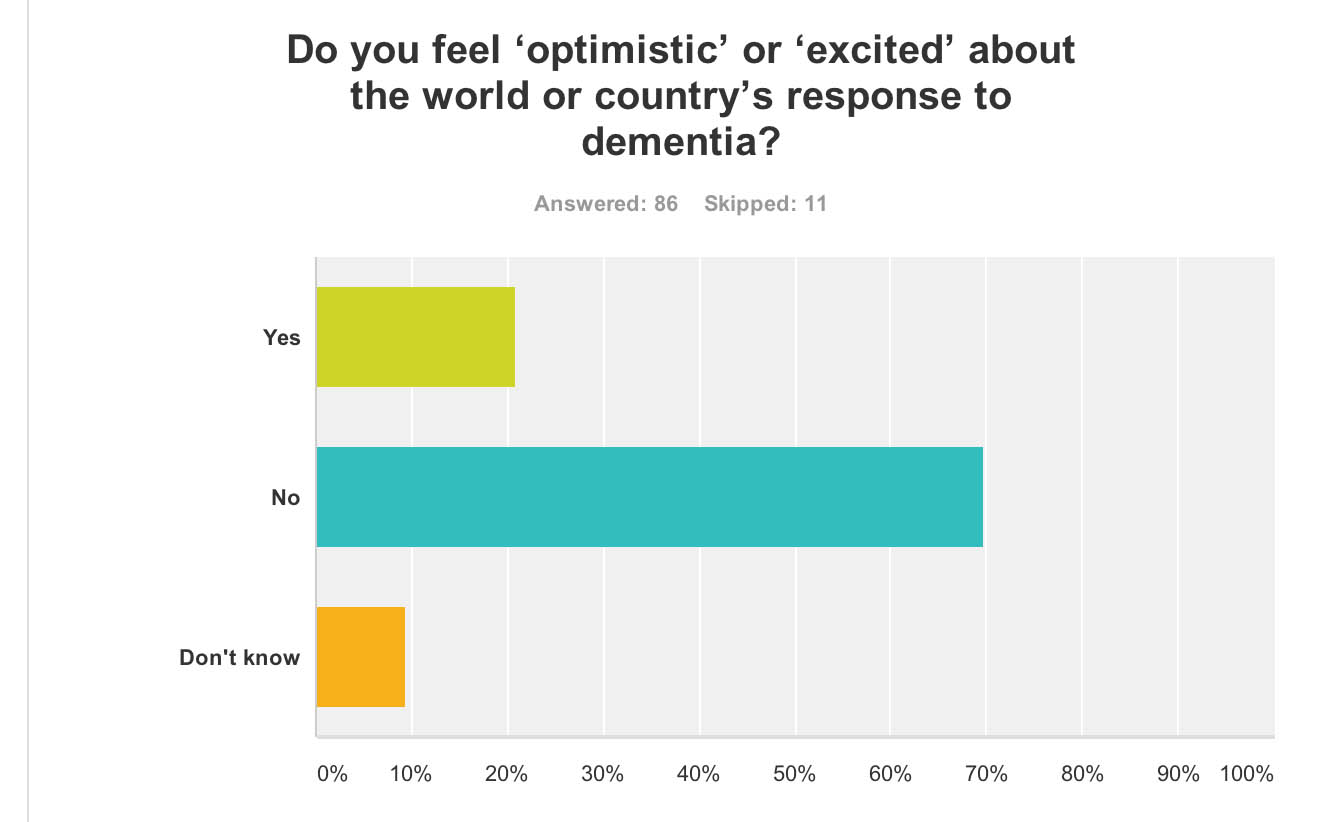

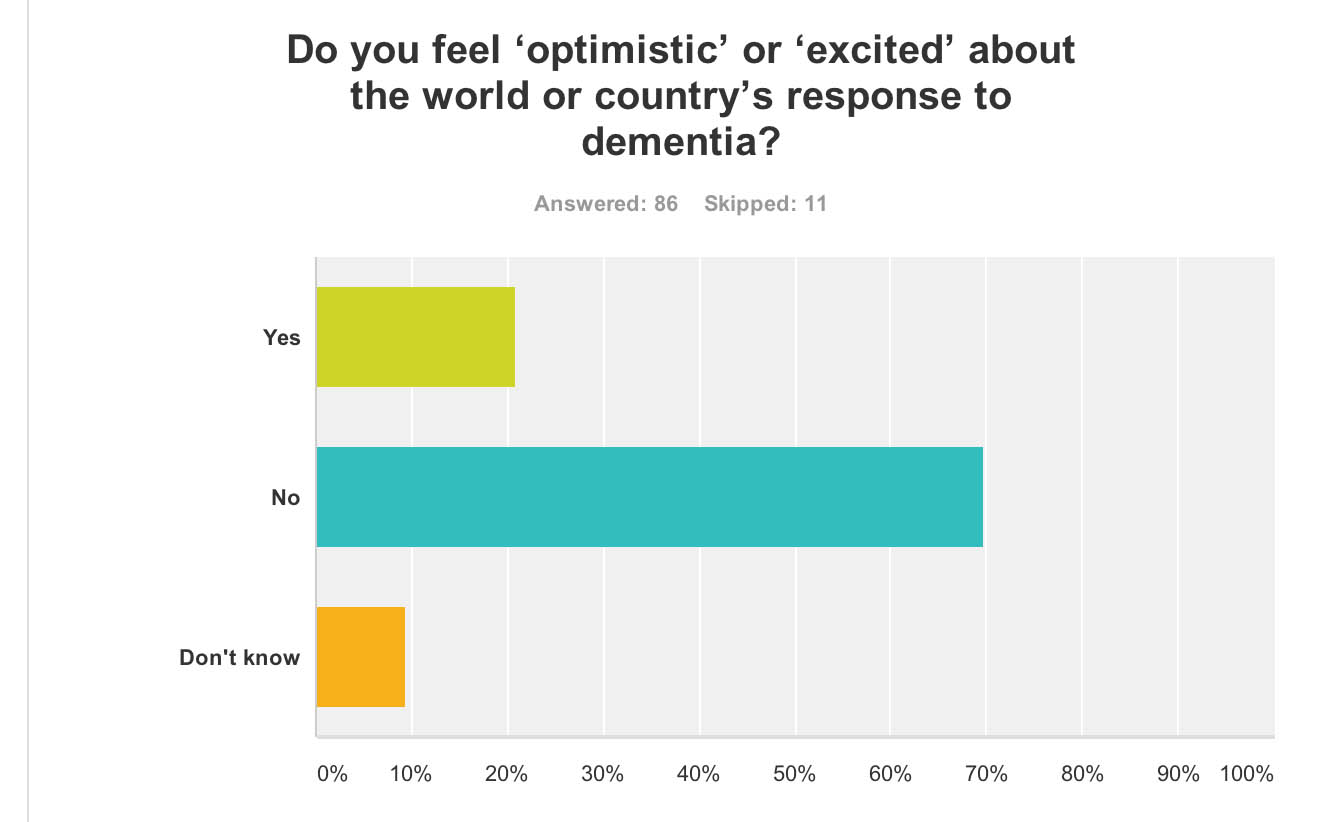

Despite all the media hype and extensive media coverage of the G8 dementia summit, 70% of people “did not feel excited about the world or country’s response to dementia” (n = 86).

But it is possibly hard to see what more could have been done.

The presentation by Pharma and politicians for their dementia agenda was extremely slick. This may be though due to a sense of politicisation of the dementia agenda, a point I will refer to below.

Early on in the meeting, World Health Organization Director-General Magaret Chan reminded the delegates – including politicians, campaigners, scientists and drug industry executives – how much ground there was to cover.

“In terms of a cure, or even a treatment that can modify the disease, we are empty-handed,” Chan said.

“In generations past, the world came together to take on the great killers. We stood against malaria, cancer, HIV and AIDS, and we should be just as resolute today,” Cameron said. “I want December 11, 2013, to go down as the day the global fight-back really started.”

It is therefore been of conceptual interest as to whether dementia can be considered in the same category as other conditions, some of which are obviously communicable. In my survey, people reported that that, before the summit, they would not have considered dementia comparable to HIV/AIDS (88%), cancer (70%), or polio (92%) (n = 86).

This is interesting, as a common meme perpetuated also by certain parliamentarians (who invariably spoke about Dementia Friends too) was that the same sort of crisis level in finding a cure for dementia should accompany what had happened for AIDS decades ago.

Biologically, the comparisons are weak, but it was argued that AIDS, like dementia now, suffered from the same level of stigma. Dementia, however, is an umbrella term encompassing about a hundred different conditions, so the term itself “a cure for dementia” is utterly moronic and meaningless.

Also in my survey, 67% of people reported that they did not feel more excited about the future of social care and support for people living with dementia (n = 85), and virtually the same proportion (66%) reported that they did not feel excited about the possibility of a ‘cure’ for dementia (defined as a medication which could stop or slow progression) (n = 85).

This reflects the reality of those people living in the present, perhaps caring for a close one with a moderate or severe dementia. It had been revealed that budget cuts have seen record numbers of dementia patients arriving in A&E during 2013. Regarding this, it was estimated that around 220,000 patients were treated in hospital as a result of cuts in social care budgets, which left them without the means to get care elsewhere.

It is known that the government has cut £1.8 billion from social care budgets, which is in addition to the pressure being applied to GP surgeries. In 2008 the number of dementia patients arriving in A&E was just over 133,000. The concern is that the Alzheimer’s Society, while working so close to deliver “Dementia Friends”, is not as effective in campaigning on this slaughter in social care as they might have done once upon a time. Currently, we now have the ridiculous spectacle of councils talking about dementia friendly communities while slashing dementia services in their community (as I discussed on the Our NHS platform recently).

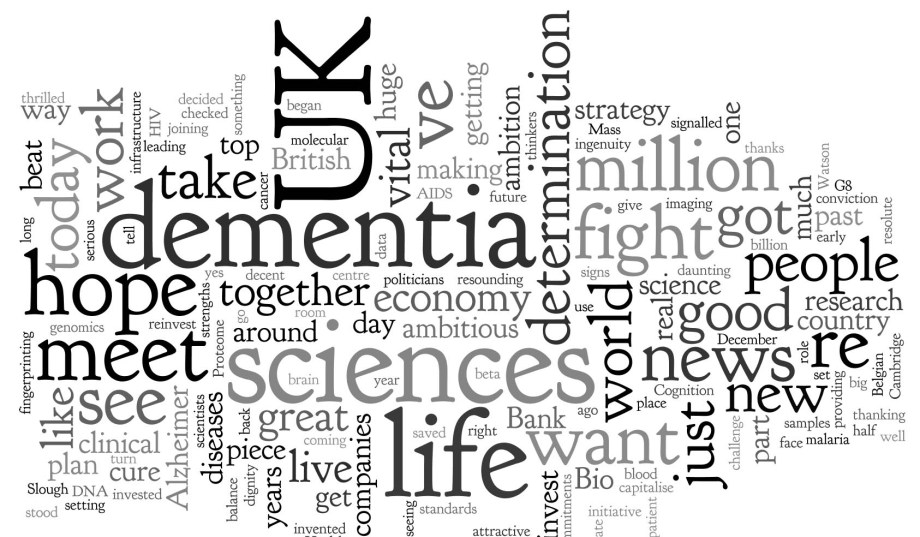

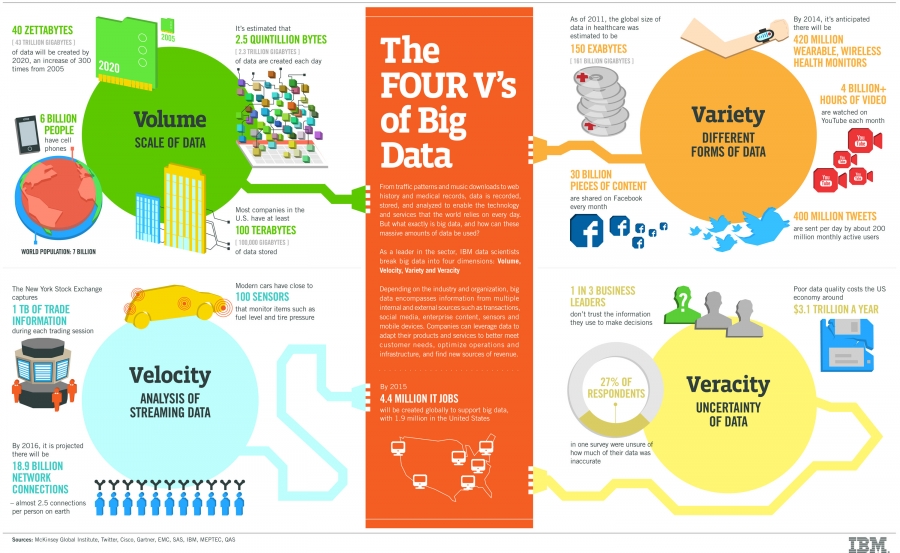

Why Big Pharma should have felt the need to breathe life into the corpse of their industry for dementia is interesting, though, in itself. Pharma obviously is ready to fund molecular biology research, and less keen to fund high quality living well with dementia, and there is also concern that this agenda has pervasively extended to dementia charities where “corporate capture” is taking place. A massive theme of the G8 dementia summit was in fact ‘personalised medicine’. For example, there is growing evidence that while two patients may be classified as having the same disease, the genetic or molecular causes of their symptoms may be very different. This means that a treatment that works in one patient will prove ineffective in another. Nevertheless, it is argued the literature, public databases, and private companies have vast amounts of data that could be used to pave the way for a better classification of patients. According to my survey, despite ‘personalised medicine’ being a big theme of the summit, strikingly 66% felt that this was not adequately explained. There’s no doubt also that the Big Pharma have been rattled by their drugs coming ‘off patent’ as time progresses, such as donepezil recently. This has paved the way for generic competitors, though it is worth noting that certain people have only just given up on the myth that cholinesterase inhibitors, a class of anti-dementia drugs, reliably slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in the majority of patients.

Who benefited?

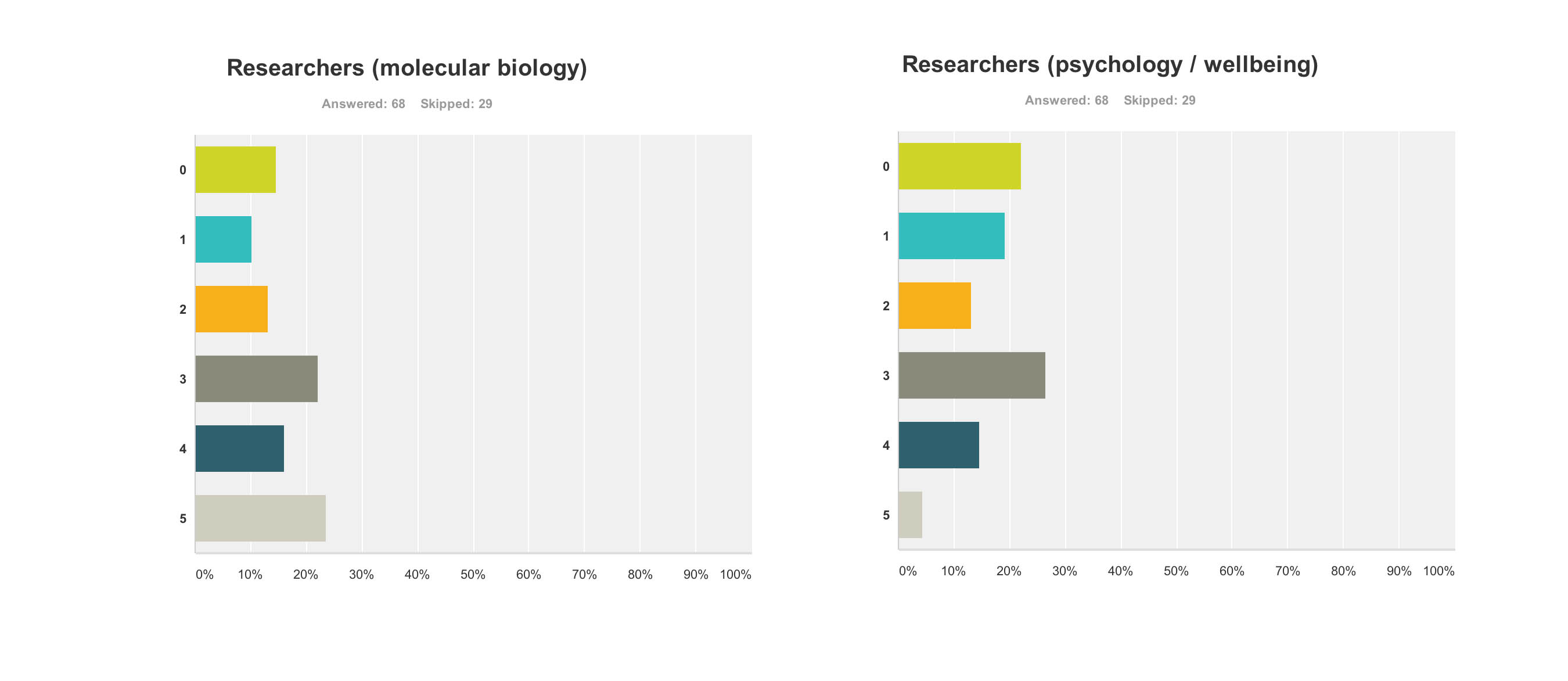

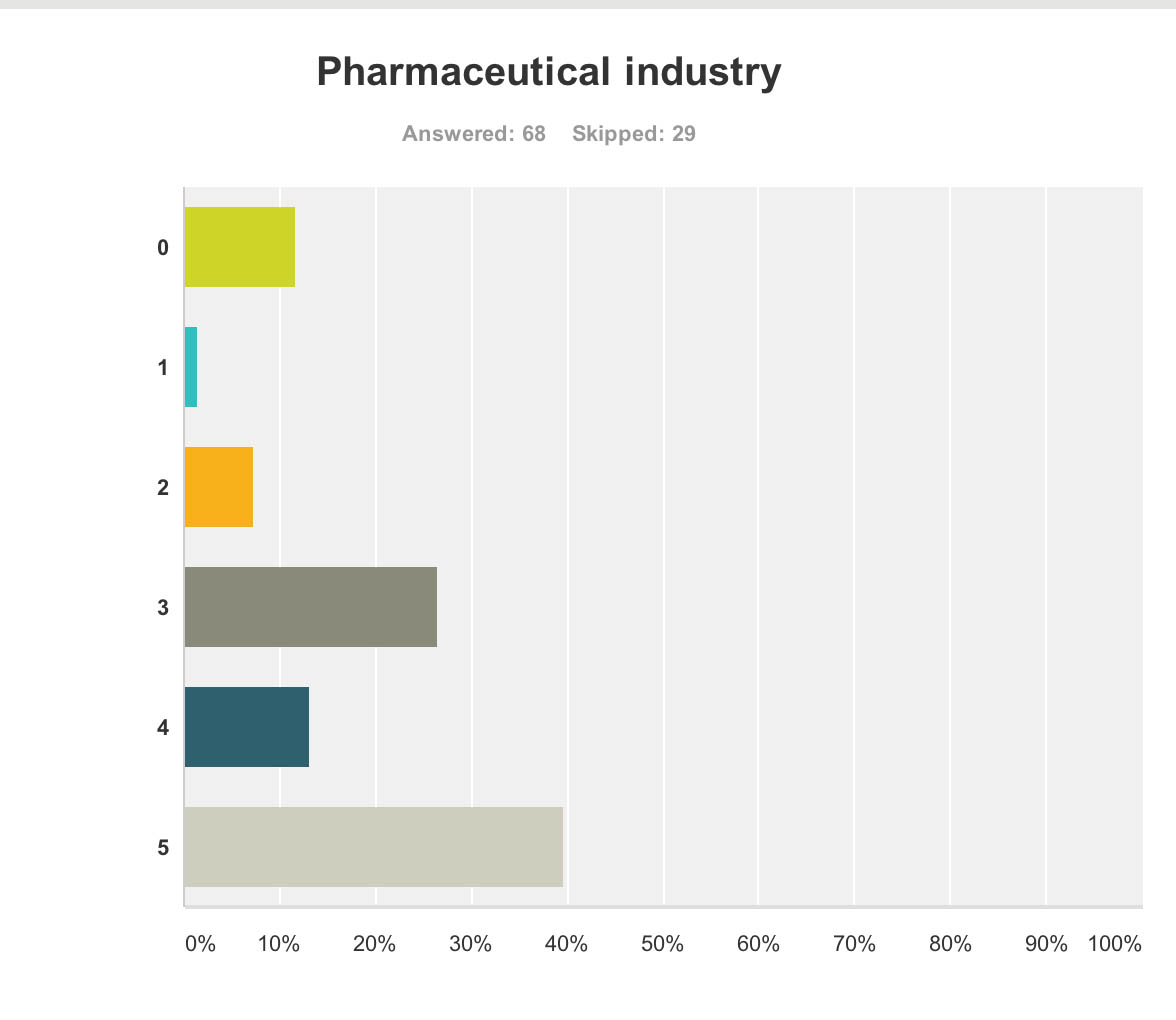

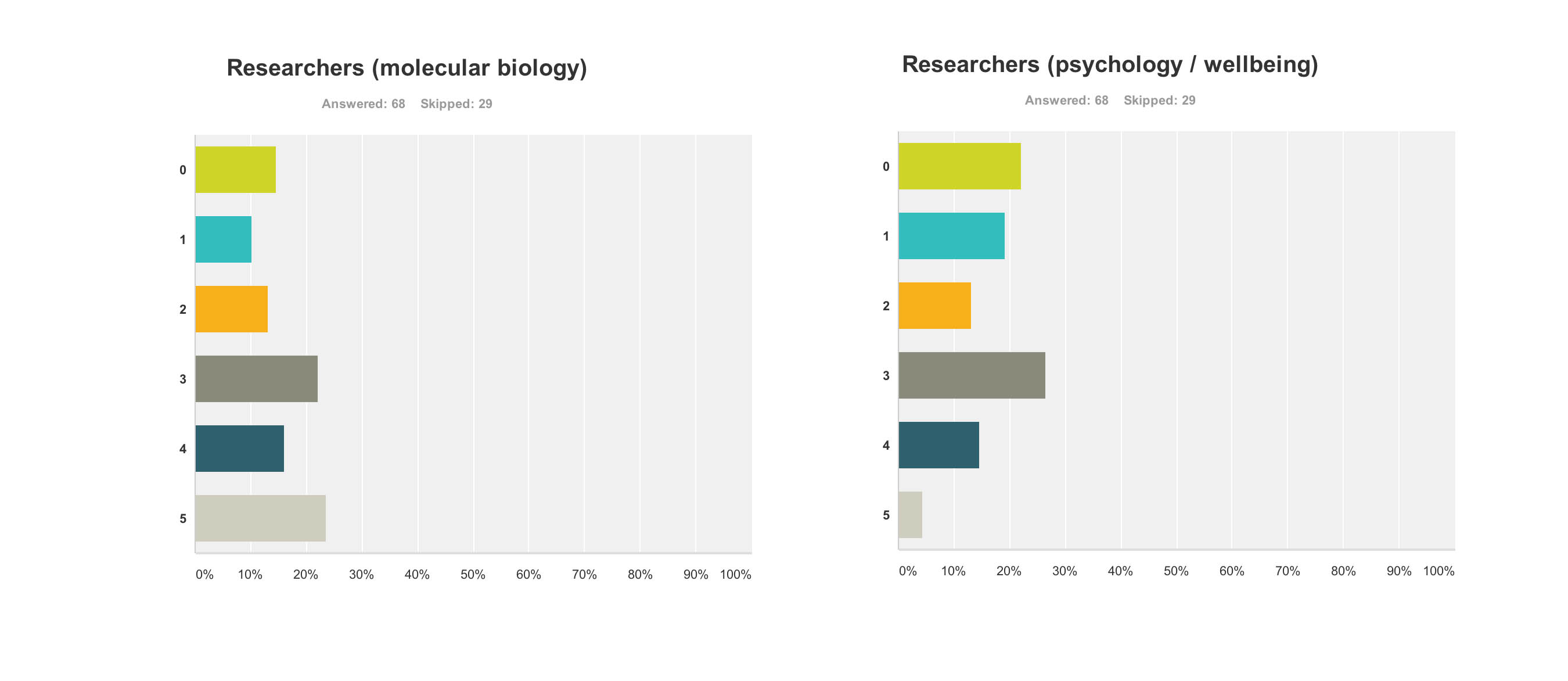

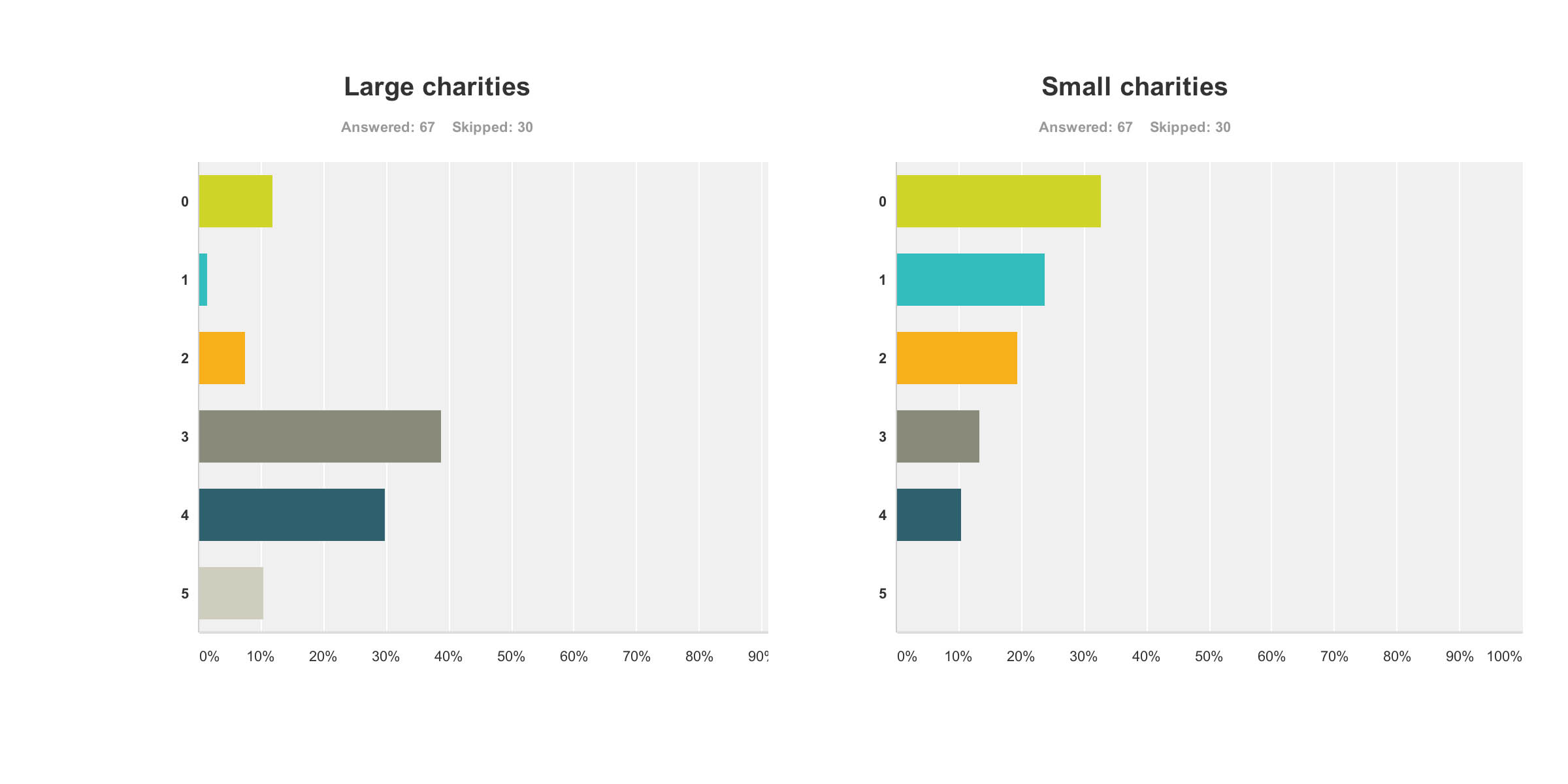

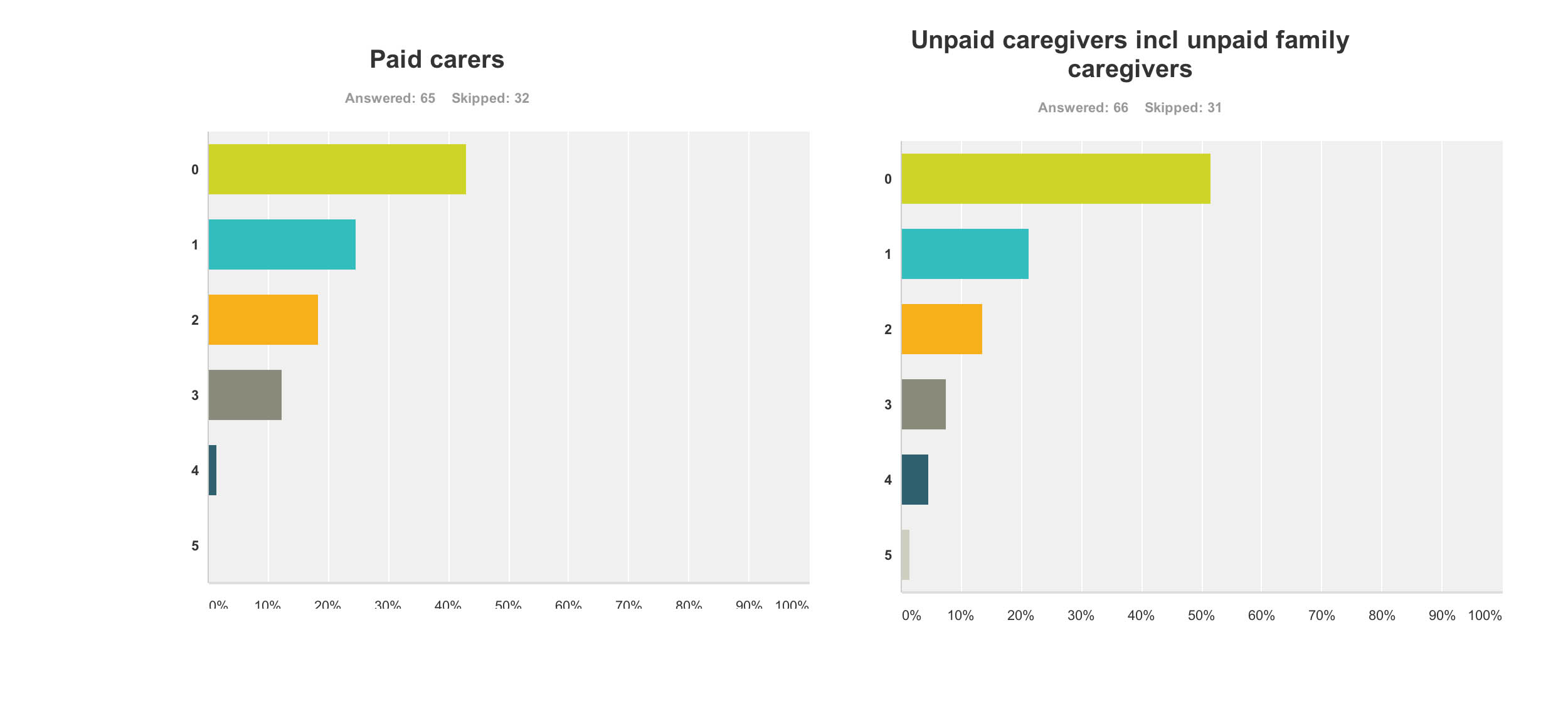

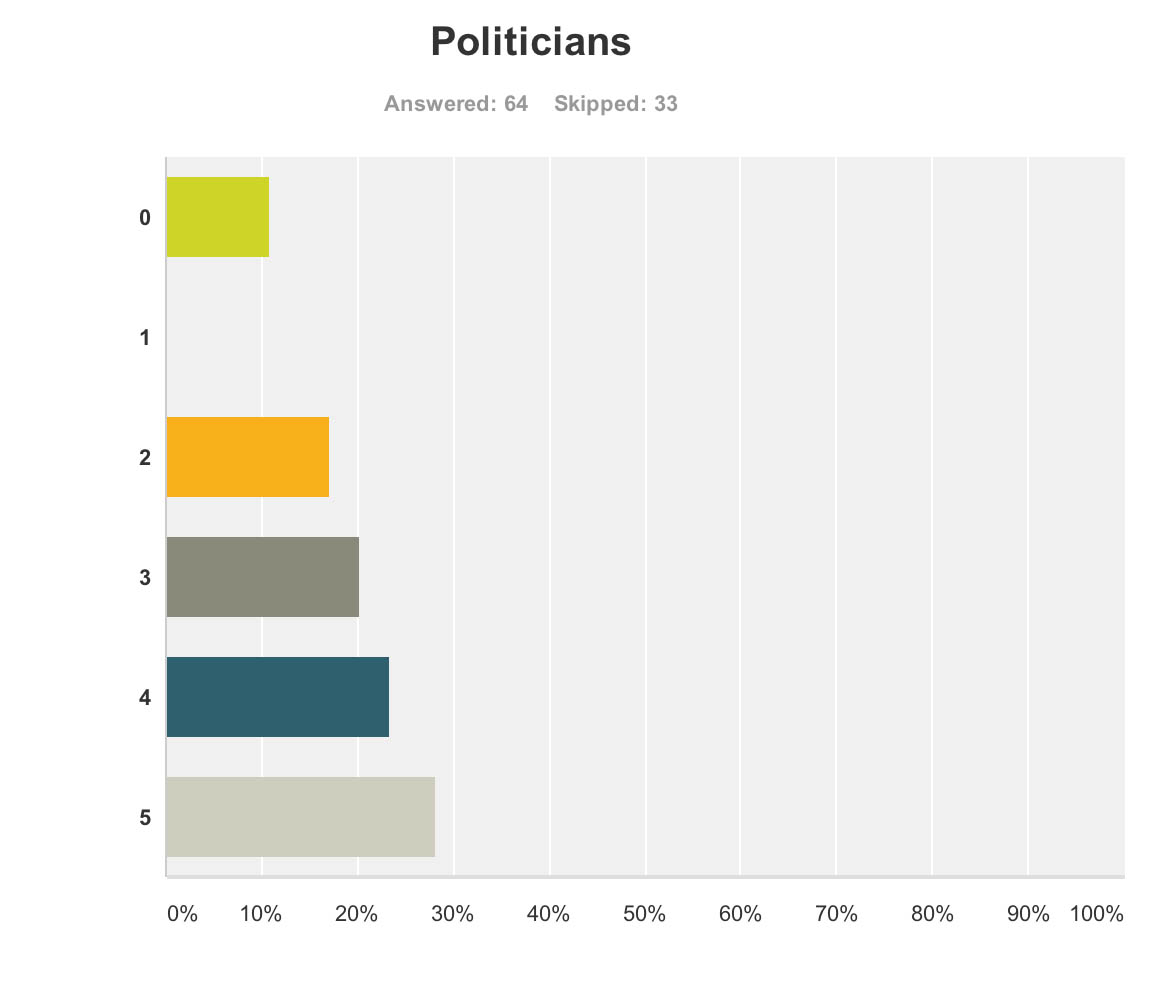

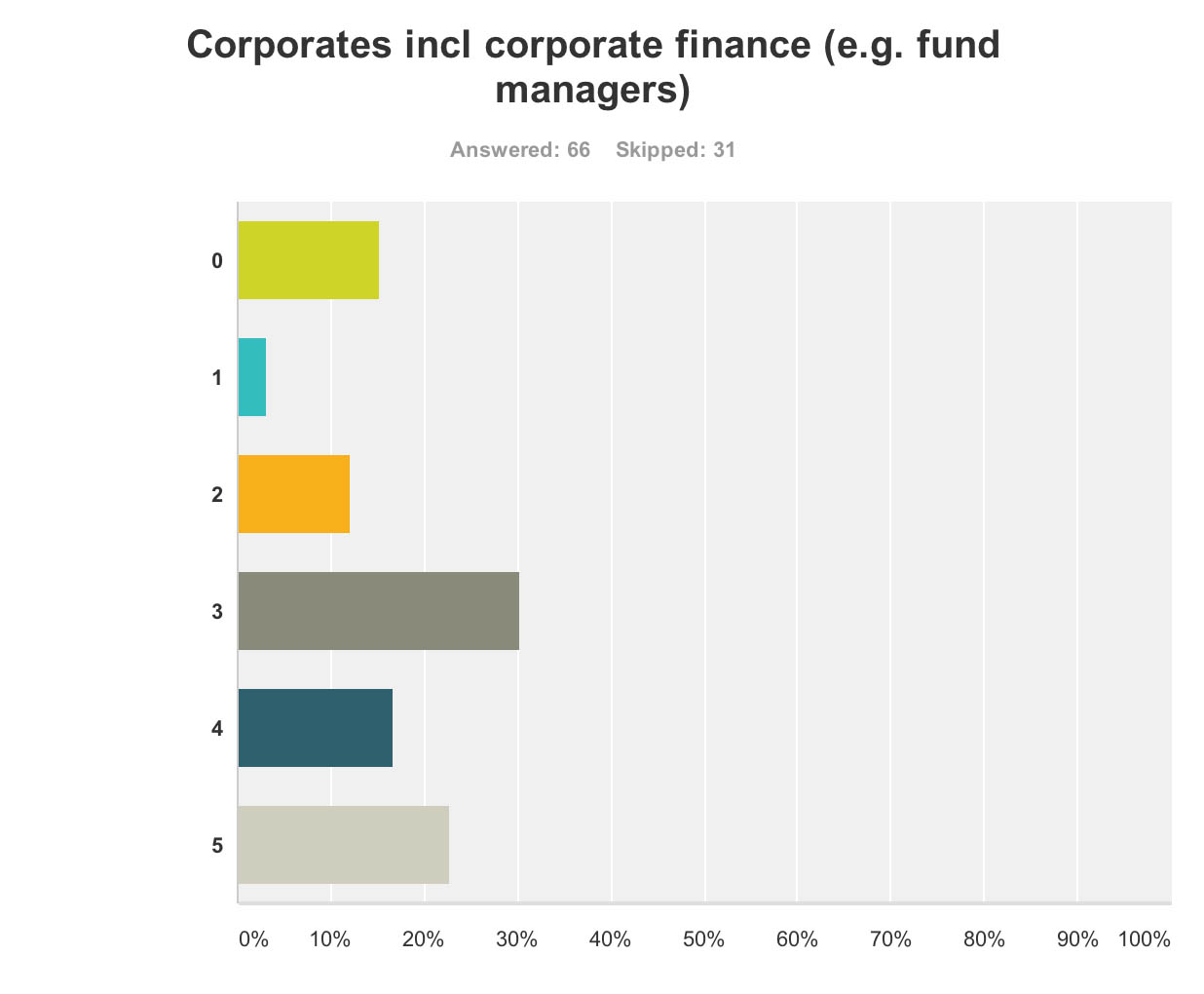

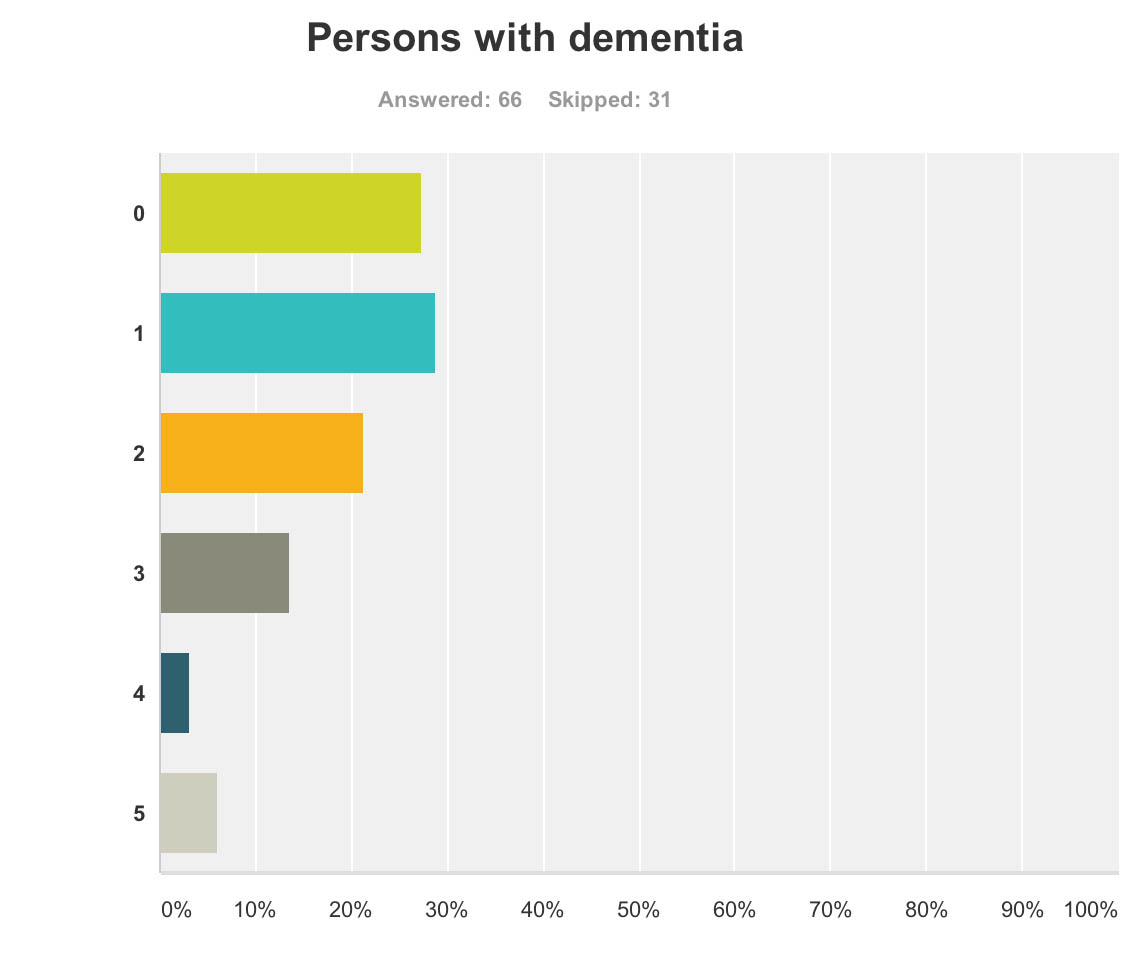

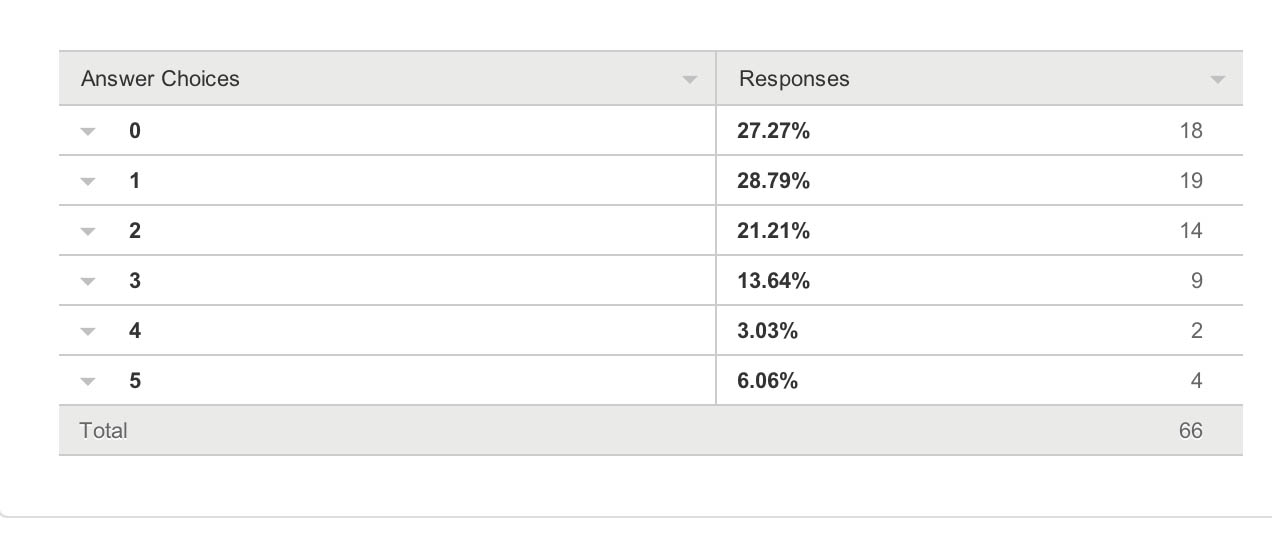

In terms of who ‘benefited’ from the G8 dementia summit, I asked respondents to rate answers from 0 (not at all) to 5 (completely).

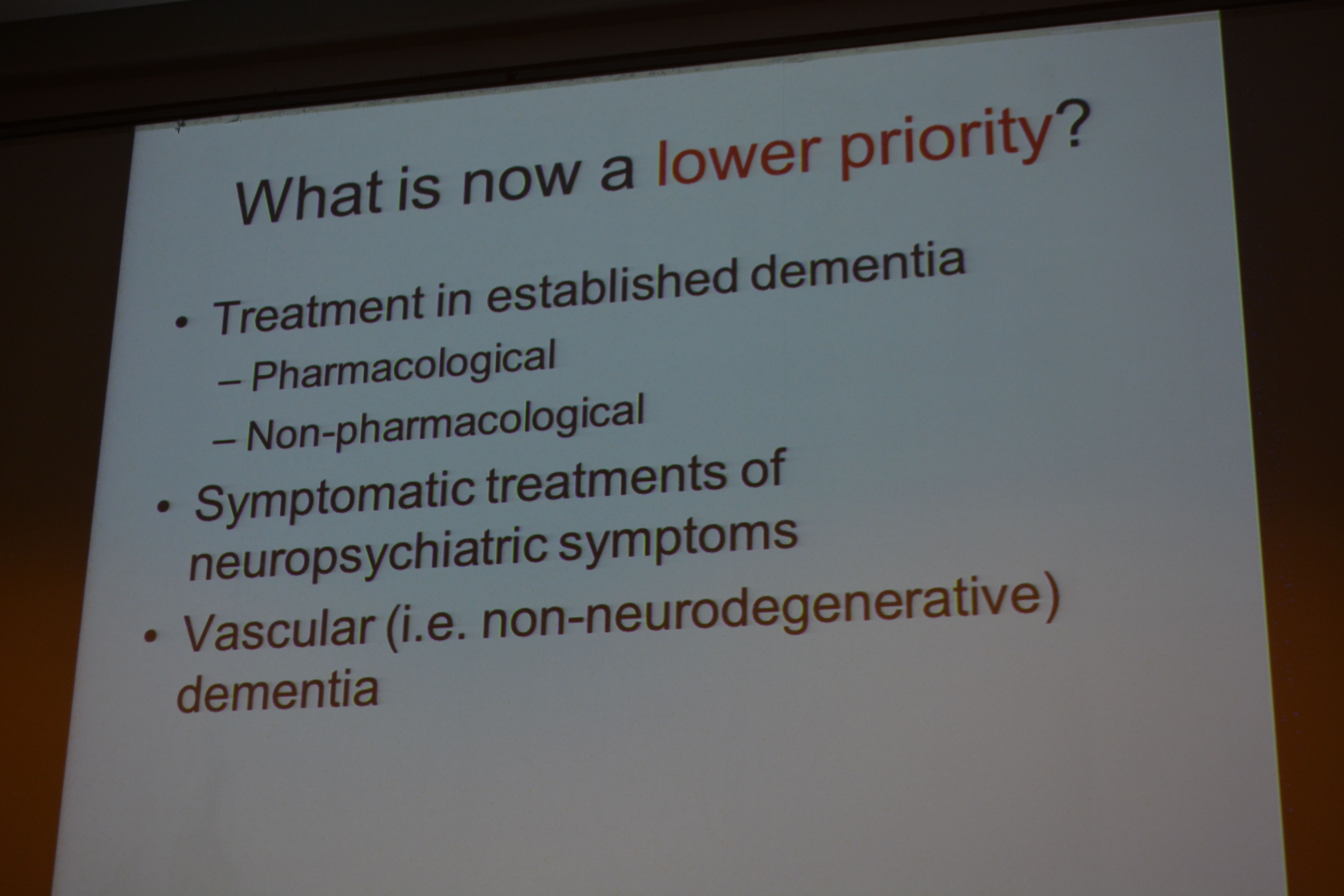

Research First of all, it doesn’t seem researchers themselves are “all in it together”. For example, these are the graphs for researchers (molecular biology) (n = 68) and researchers (wellbeing) (n = 68), with rather different profiles (with the public perceiving that researchers in molecular biology benefited more). This can only be accounted for by the fact there were many biochemical and neuropharmacological researchers in the media coverage, but no researchers in wellbeing.

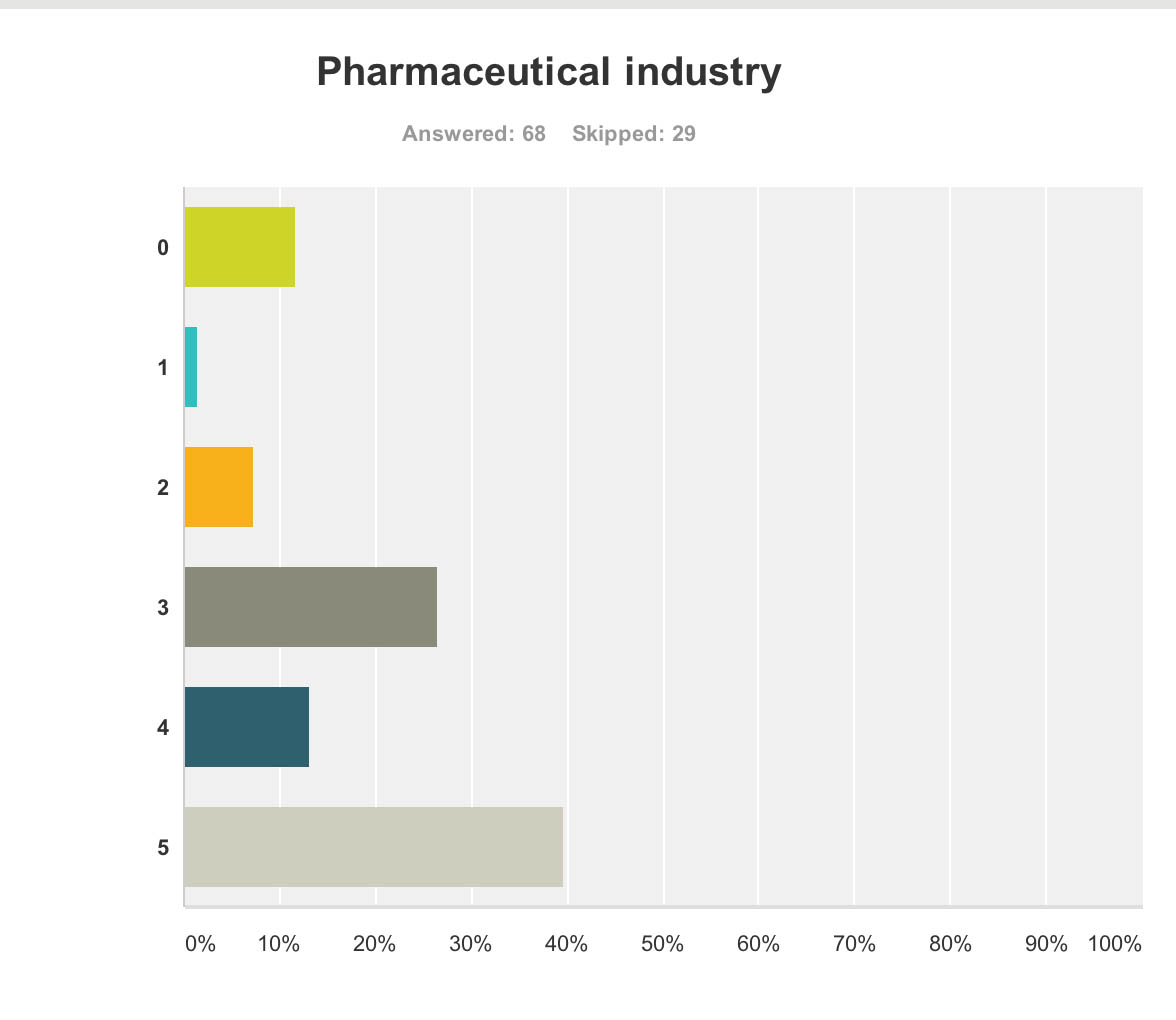

Pharmaceutical industry But the survey clearly demonstrated that the pharmaceutical industry were perceived to be the big winners of the G8 dementia (n = 68).

Ministers are hoping a government-hosted summit on dementia research will help boost industry’s waning interest in the condition, and to some extent campaigners have only themselves to blame for pinning their hopes on this one summit.

The G8 Summit came amidst fears the push to find better treatments is petering out, and it is still uncertain how effective some drugs currently in Phase III trials might be, given their problems with side effects and finding themselves into the brain once delivered.

And the breakdown is as follows:

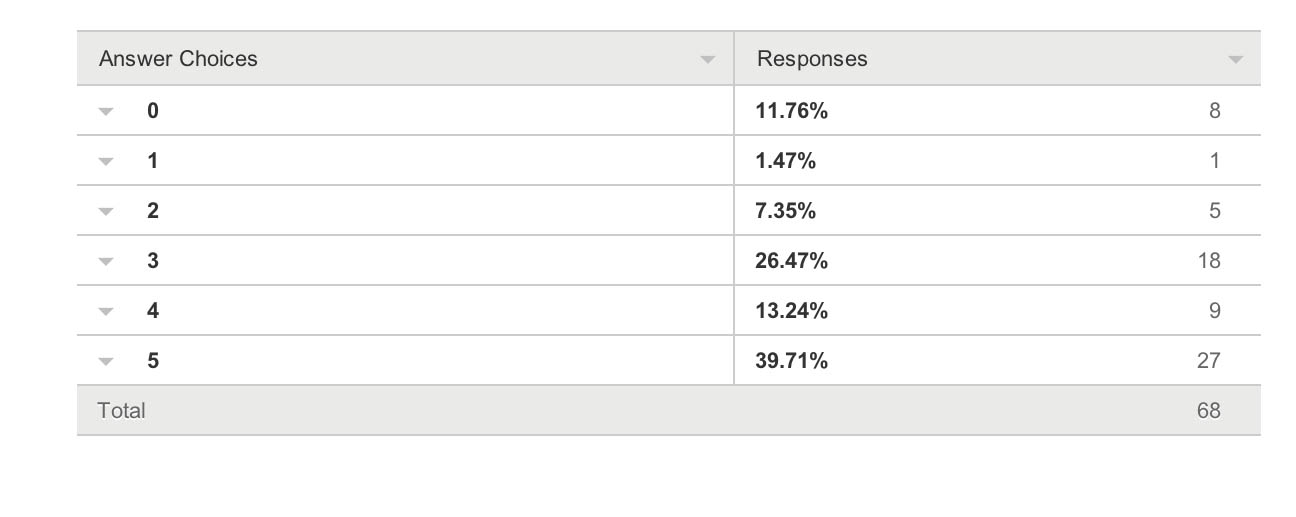

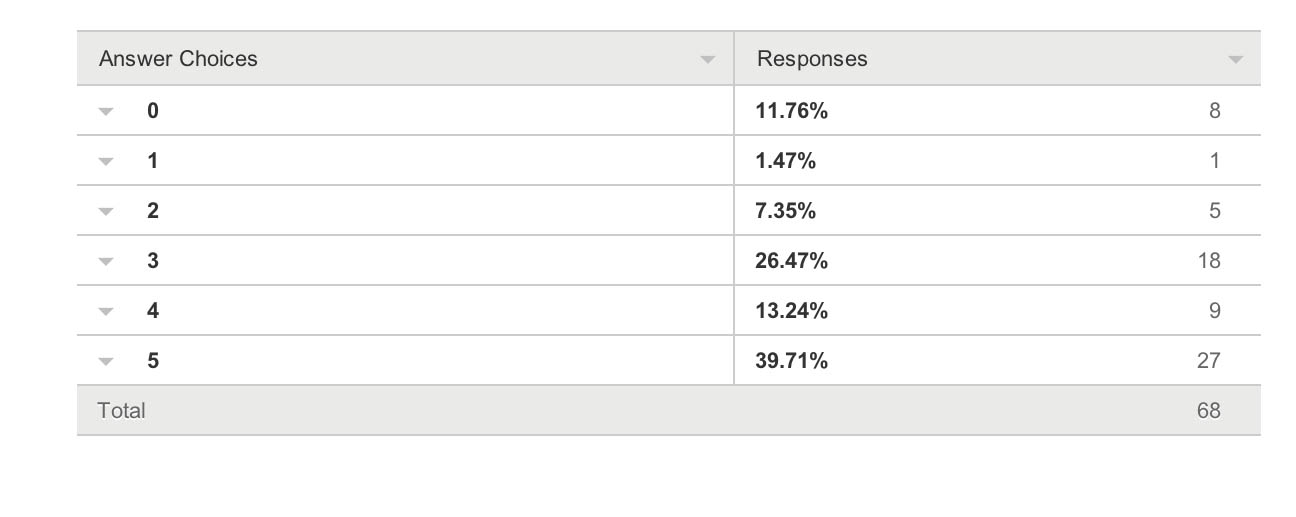

Charities The survey also revealed a troubling faultline in the ‘choice’ of those who wish to support dementia charities, and potential politicalisation of the dementia agenda. It has been particularly noteworthy that this recent initiative in English policy was branded “the Prime Minister Dementia Challenge”, and ubiquitously the Prime Minister was (correctly) given credit for devoting the G8 to this one topic.

A previous press release had read,

“Launched today by Prime Minister David Cameron, the scheme, which is led by the Alzheimer’s Society, people will be given free awareness sessions to help them understand dementia better and become Dementia Friends. The scheme aims to make everyday life better for people with dementia by changing the way people think, talk and act. The Alzheimer’s Society wants the Dementia Friends to have the know-how to make people with dementia feel understood and included in their community.. By 2015, 1 million people will become Dementia Friends. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. The scheme has been launched in England today and the Alzheimer’s Society is hoping to extend it to the rest of the UK soon. Each Dementia Friend will be awarded a forget-me-not badge, to show that they know about dementia. The same forget-me-not symbol will also be used to recognise organisations and communities that are dementia friendly. The Alzheimer’s Society will release more details in the spring about what communities and organisations will need to do to be able to display it.”

Therefore, the perception had arisen amongst the vast majority of my survey respondents that large charities were big winners from the G8 dementia summit. This is perhaps unfair as there was not much representation from other big charities apart from the Alzheimer’s Society, for example Dementia UK or the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

I feel that this distorted public perception in the charity sector for dementia is extremely dangerous.

And this finding is reflected in the corresponding graph for ‘small charities’. Small charities were not represented at all in any media coverage, save for perhaps ambassadors of smaller charities there in a personal capacity at the Summit.

The numbers sampled for their views on large and small charities were both 67.

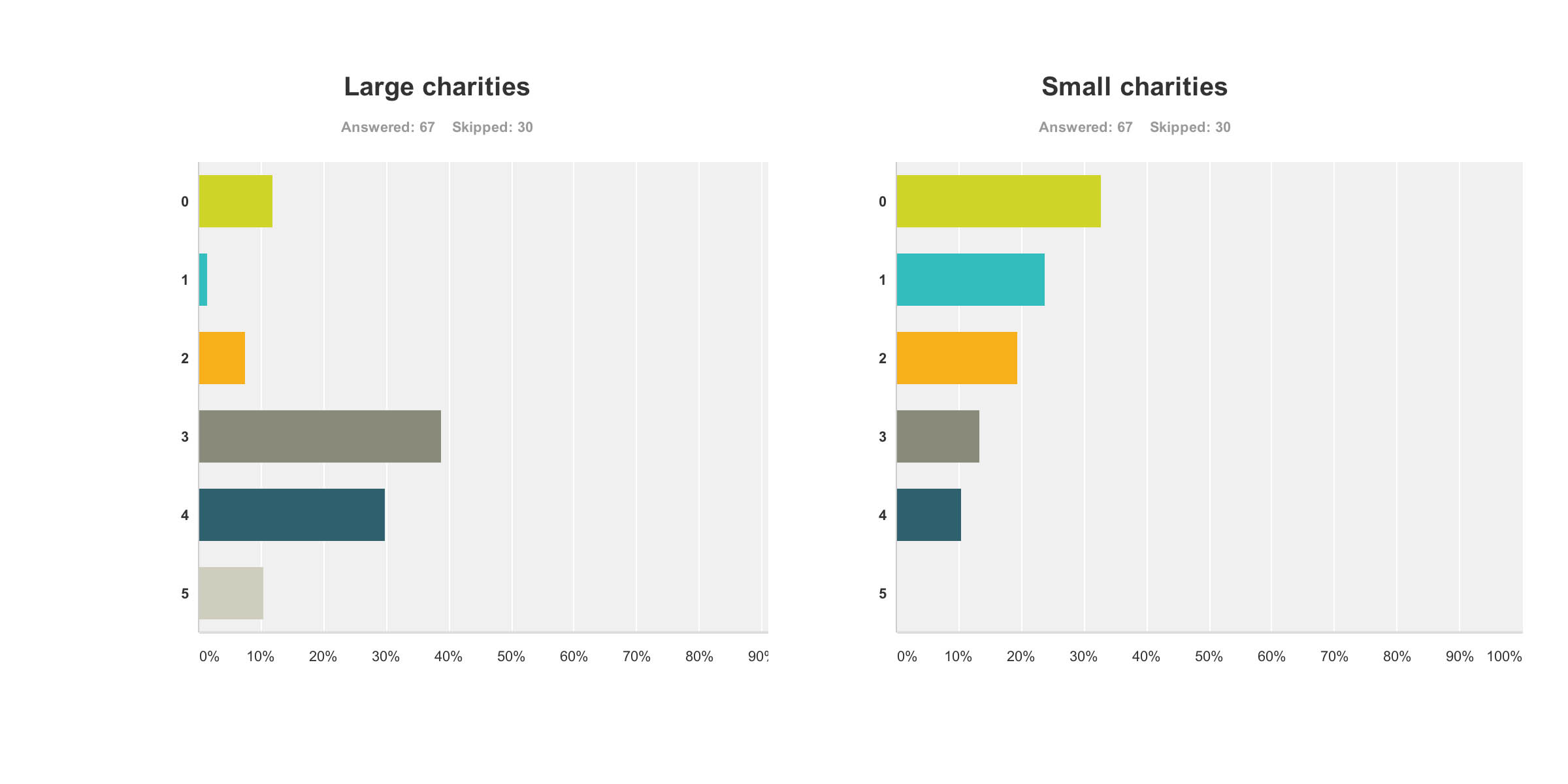

Paid carers and unpaid caregivers

The major elephant in the room, or maybe more aptly put an elephant who wasn’t invited to be in the room at all, was the carers’ community.

Only recently, for example, it’s been reported from Carers UK that half of the UK’s 6.5 million carers juggle work and care – and a rising number of carers are facing the challenge of combining work with supporting a loved one with dementia. The effects of caring for a person with moderate or severe dementia are known to be substantial, encompassing a number of different domains such as personal, financial and legal. It is also known that without the army of millions of unpaid family caregivers the system of care for dementia literally would collapse.

These are the graphs for paid (upper panel) and unpaid (lower panel) carers and caregivers (n = 65 and n = 66 respectively), with the most common response being “not at all benefiting”.

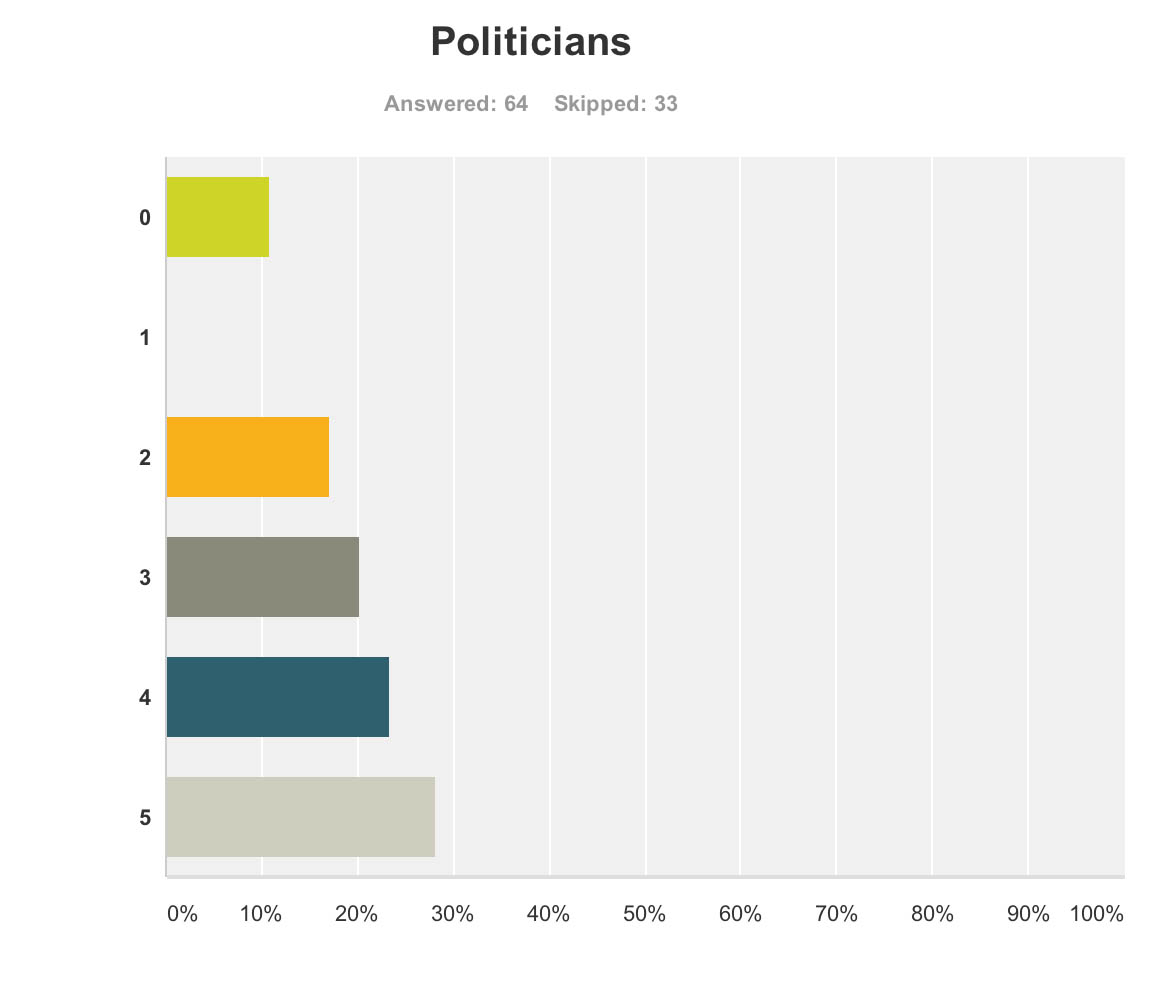

Politicians

But when asked if the politicians benefited, the result was very different.

Admittedly, few politicians were in attendance from the non-Government parties in England, and none from the main opposition party was given an opportunity to give a talk.

Both Jeremy Hunt and David Cameron gave talks. There is clearly not a lack of cross-party consensus on the importance of dementia, evidenced by the fact that the last English dementia strategy ‘Living well with dementia’ was initiated under the last government (Labour) in 2009.

The overall impression from 64 respondents to this question that politicians benefited, and some thought quite a lot.

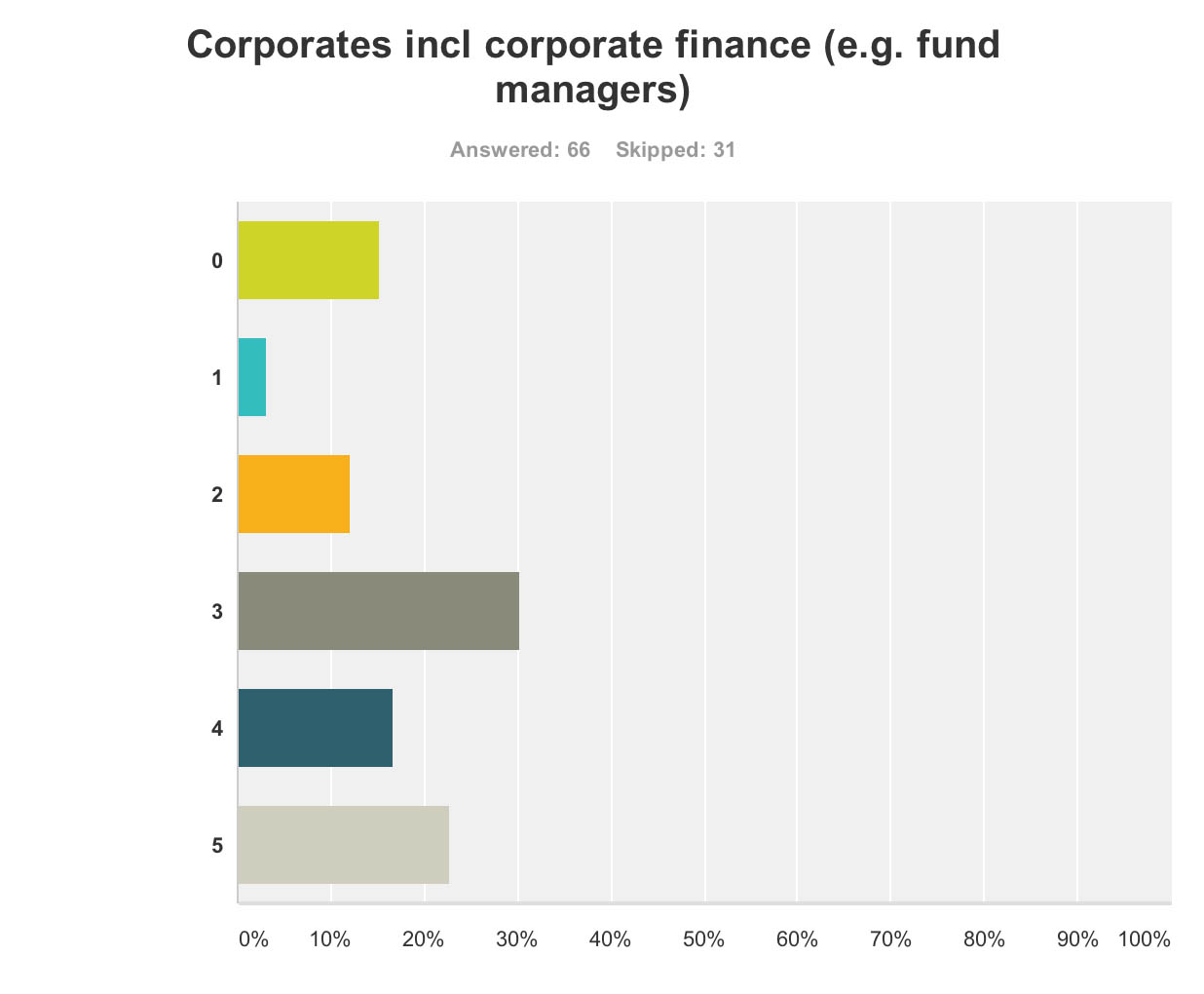

Corporate finance A lot of discussion was about ‘investment’ for ‘innovation’ in drug research. Andrea Ponti is a highly influential man. He has been Global Co-head of Healthcare Investment Banking and Vice Chairman of Investment Banking In Europe of JPMorgan Chase & Co. since 2008. Mr. Ponti joined JPMorgan from Goldman Sachs, where he was a Partner and Co-head of European healthcare, consumer and retail investment banking, having founded the European healthcare team in 1997.

At the G8 dementia summit, Ponti advised that biotechnology and drug research can be a ‘risky’ investment for funders, rebalance of risk/reward needed. Ponti specifically made the point the rewards for investing in drug development had to be counterbalanced by the potential risks in data sharing (which are not insubstantial legally across jurisdictions because of privacy legislation).

Anyway, in summary, it was perhaps no surprise that my survey respondents felt that corporate finance were big winners of the summit (n = 65).

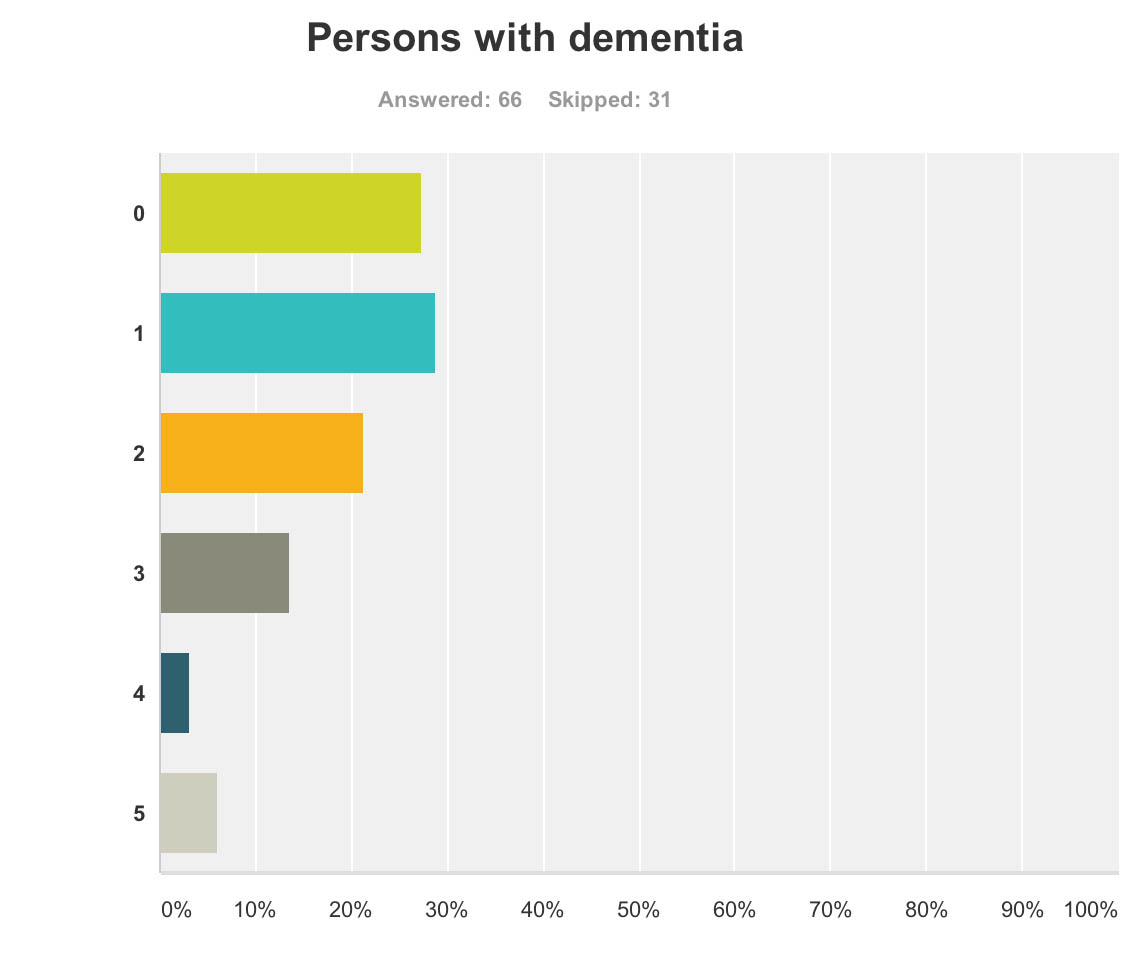

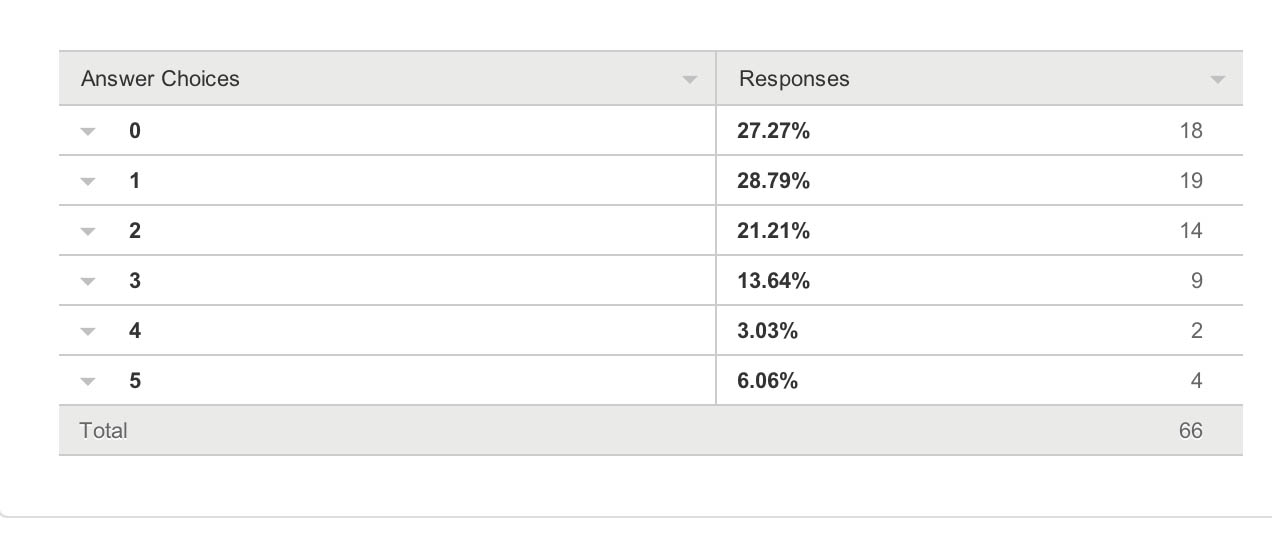

Persons with dementia And also for persons with dementia themselves?

One would have hoped that they would have been big winners according to my survey respondents, but the graph shows a totally different profile (with a minority of respondents rating that they benefited much.)

This is very sad.

66 answered this question.

The overall picture was this.

And the breakdown of results was this.

What will people do next?

Finally, it seemed as if the G8 Dementia Summit produced a ‘damp squib’ response with people in the majority neither more or less likely to donate to dementia charities (69%), donate to dementia care organisations (74%), get involved in befriending initiatives (72%), talk to a neighbour living with dementia or talk to a caregiver of a person living with dementia (58%), or get involved in dementia research (69%) (n varying from 73 to 78).

Limitations

Respondents were all in the UK, but the G8 dementia summit was clearly targeted in a multi-jurisdictional way.

It could be that there is huge bias in my sample, towards people more interested in care rather than Pharma. My follower list does include a significant number of people living with dementia or who have been involved in caring for people with dementia.

Conclusion

It would be interesting to know of any in-house reports from other organisations as to how they perceived they felt benefited from the G8 dementia, for example from patient representative groups, Big Pharma, carers and the medical profession. Pardon the pun, but the results taken cumulatively demonstrate a very unhealthy picture of the public’s perception in the dementia agenda in England, who calls the shots, and who benefits.

Given that this G8 dementia was to a large extent supposed to establish a multinational agenda until 2025, in parallel to the multinational nature of the response of the pharmaceutical industry, for those of us who wish to promote living well with dementia, it is clear some people are actually the problem not the solution.

This is incredibly sad for us to admit, but it’s important that we’re no longer in denial over it.