Decisions are fundamental to our lives.

Decision making is a fundamental and complex skill which is crucial at any age. We all have to face decisions regarding their health care, medical treatment, retirement, housing, transport, and finances, for example.

We not only have to consider the benefit of a decision for their current living situation, but also to anticipate the consequences of decisions of such actions in the nearer and farer future. We need to hold the decision in my memory for long enough to think through strategically the options, and be able to action an outcome.

Everyday life requires numerous and fast decisions. Often these decisions have an uncertain result. Wrong decisions may thus have severe consequences in several domains.

Disturbances in an ability to make decisions or to anticipate the possible consequences of decisions can result in massive problems.

In the last decade in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive neurology, there has been an increasing interest to investigate neural basis of decision-making abilities and disturbances both in healthy subjects and to people where there has been some disruption.

But we have been able to build up a coherent picture of this using neuropsychological and neuroimaging techniques.

An assessment of cognitive deficits in neurodegenerative diseases has focused so far almost entirely on memory, language, attention, visuospatial perception and executive functioning (Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010).

In the past decade, however, the study of decision-making in these conditions has increased, prompting the development of new tasks that have enabled this cognitive process to be readily assessed. In clinical practice, it is not uncommon to find early persons with behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) who, to a considerable extent, are intellectually unimpaired, while relatives and caregivers depict a strikingly different picture: they claim that these patients show severe changes in their behaviour and real-life decision-making skills (e.g. Rahman et al., 1999; Manes et al., 2011).

The literature has so able to identify the orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices as being critical to decision-making (Rosenbloom, Schmahmann and Price, 2012).

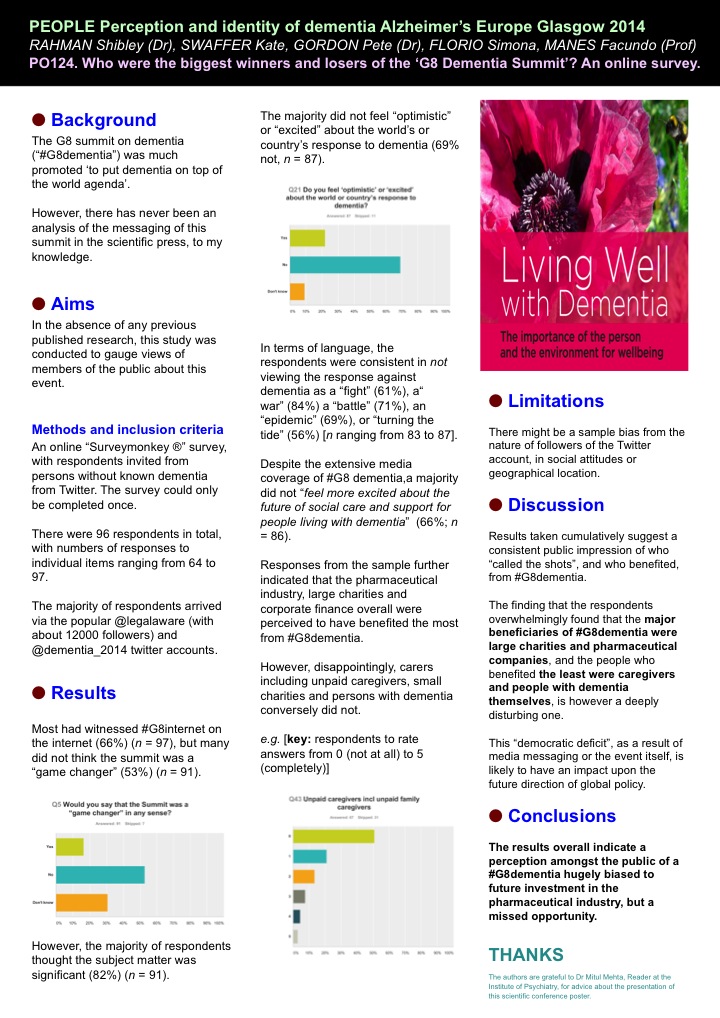

A schematic view of the important neural substrates proposed by Rahman and colleagues (Rahman et al., 2001) is shown in Figure 1.

Rahman and colleagues showed that patients with behavioural variant frontemporal dementia exhibited a profile of risk-taking, not impulsive, behaviour in decision-making, suggestive of dysfunction in the ventromedial prefrontal or orbitofrontal cortex. Kloeters and colleagues (Kloeters et al., 2013), fourteen years later, published results showing that atrophy in the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala correlated with performance on the Iowa Gambling Task used in their study to examine decision-making.

A large proportion of human cognitive social neuroscience research has focused on the issue of decision-making thus far.

Impaired decision-making is a symptomatic feature of a number of neurodegenerative diseases, but the nature of these decision-making deficits depends on the particular disease.

Once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia. Each person with dementia will have a cognitive profile according how far progressed the condition has reached, and the extent to which functional problems are perceived. This might depend on the likely diagnostic category in which a patient living with dementia finds himself or herself.

Examining the qualitative differences in decision-making impairments associated with different neurodegenerative diseases provides potentially valuable information regarding the underlying neural basis of decision-making.

A good account of decision-making in different neurological conditions including dementia is provided by Brand, Labudda and Markowitsch (2006).

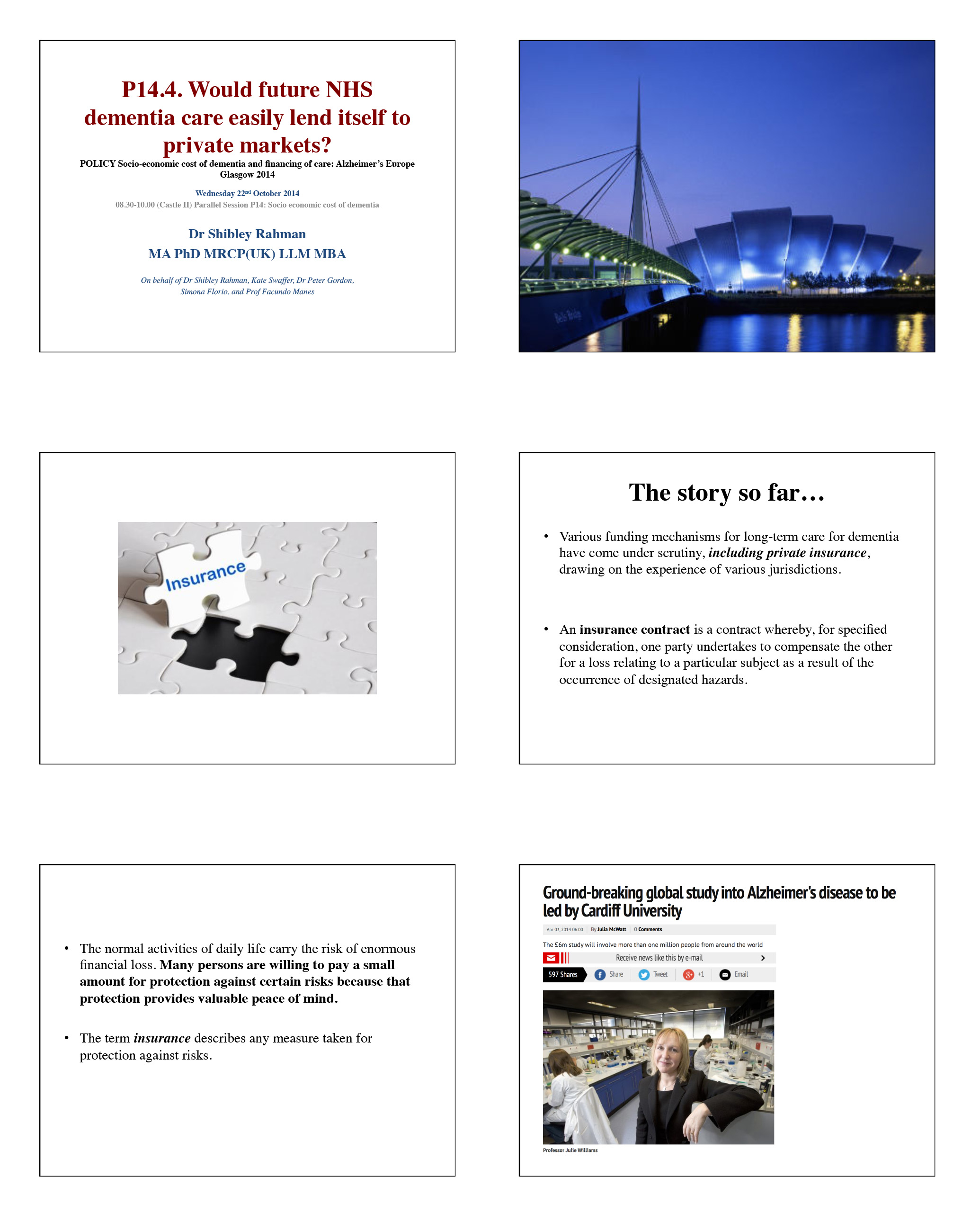

Figure 2 shows a schematic view of some of the key processes.

The features of their model are as follows.

General problem solving strategies, also stored in long-term memory, need to be recalled in order to evaluate which strategy seems to be appropriate in order to decide advantageously. The recall of this information, including personal autobiographical experiences and general strategies that have been developed during life, is triggered and controlled by executive components, for example cognitive flexibility.

In working memory, the features of the current decision and the retrieved information from long-term memory are combined to generate or initiate a current decision strategy that guides the decision.

In this process, “somatic markers”, which means biasing signals from the body or mental representations of them, can also guide the selection of an appropriate strategy. The decision itself leads to positive or negative feedback (e.g., gain or loss of a specific amount) that activates an bodily autonomic response.

The feedback – or the somatic markers, which are the results of the emotional feedback – can also result in an alteration of the information stored in long-term memory as well as – in a more direct way – the representation of somatic markers associated with comparable decisions.

The comparison of the profiles of decision making in different conditions, which can cause dementia, are arguably helpful in predicting what the person with dementia might expect. Several studies have reported altered decision-making in Parkinsons’s disease (Perretta et al., 2005) and pathological gambling has been found in Parkinsons’s disease patients with L-Dopa medication (Weintraub et al., 2006) attributing a key role to the chemical dopamine in taking risky decisions.

Recent studies also investigated decision-making in Huntington’s disease and found that learning and memory processes, rather than motivational processes, are responsible for decision-making deficits in this group (Busemeyer and Stout, 2002).

Hampton and O’Flaherty (2007, some years ago, mapped out the neural substrates of reward-related decision making with functional MRI. They identified that the combined signals from three specific brain areas (anterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, and ventral striatum) were found to provide all of the information sufficient to decode subjects’ decisions out of all of the regions studied.

These findings appear to implicate a specific network of regions in encoding information relevant to subsequent behavioral choice. Evidence for the important role of the orbitofrontal cortex and the amygdala in decision-making particularly under ambiguous conditions comes from a recent study by Hsu and colleagues (Hsu et al., 2005)).

Dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT), the cause of the most cases of dementia worldwide, is typically characterised by typical structural, neurochemical and cognitive changes as the disease progresses.

Pathological changes in mild DAT affect primarily the medial temporal lobes and limbic structures (e.g., entorhinal cortex, hippocampus), and then extend to the association cortices of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes (Braak and Braak, 1991).

Ha and colleagues have argued that the changes in DAT fundamentally alter the frames of reference for making decisions (Ha et al., 2012).

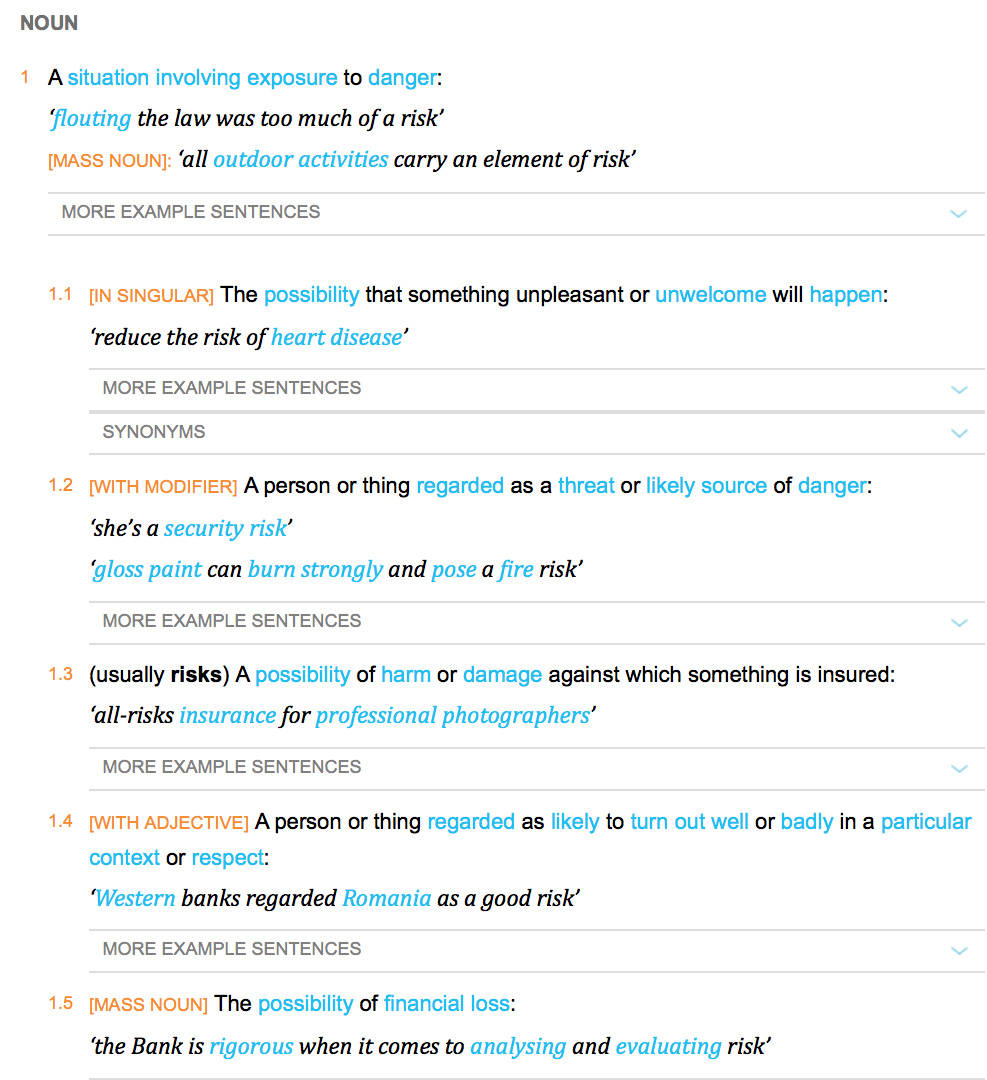

The study by Delazer and colleagues further highlighted important differences in decision-making between mild DAT patients and healthy controls (Delazer et al., 2007). Findings from the study by Sinz and colleagues are consistent with the notion that decisions under ambiguity as well as decisions under risk are impaired in mild DAT (Sinz et al., 2008). It may thus be expected that patients with mild DAT have difficulties in taking decisions in everyday life situations, both in cases of ambiguity (information on probability is missing or conflicting, and the expected utility of the different options is incalculable) and in cases of risk (outcomes can be predicted by well-defined or estimable probabilities).

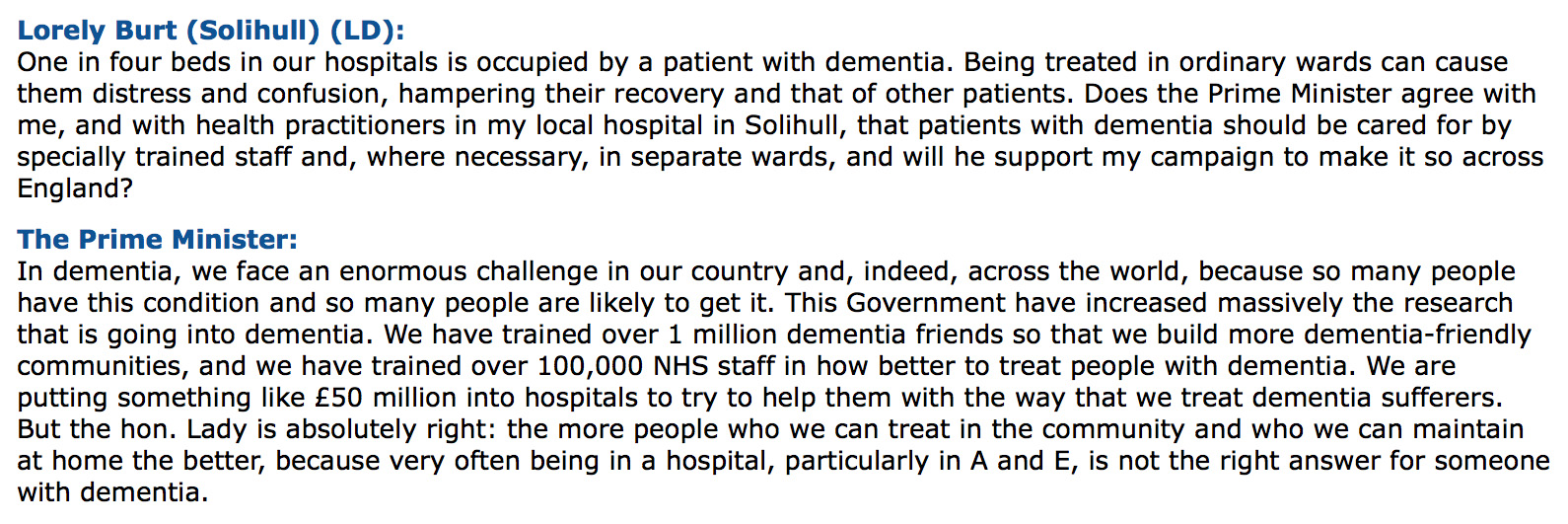

The legal instrument to assess capacity through the Mental Capacity Act (2005) is very blunt. Characterising an ability of a person living with dementia to make optimal decisions is essential for giving confidence to that person (and those closest to him and her) that such risks are being managed appropriately.

It is likely that the implementation of the Mental Capacity Act will come under increasing scrutiny, in parallel with advances in decision-making research in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive neurology.

References

Braak, H., Braak, E. (1991) Neuropathological staging of Alzheimer-related changes, Acta Neuropathologica (Berl), 82, pp. 239–259.

Brand, M., Labudda, K., Markowitsch, H.J. (2006) Neuropsychological correlates of decision-making in ambiguous and risky situations, Neural Netw, 19(8), pp. 1266-76.

Busemeyer, J. R., Stout, J. C. (2002) A contribution of cognitive decision models to clinical assessment: Decomposing performance on the Bechara gambling task, Psychological Assessment, 14, pp. 253–262.

Delazer, M., Sinz, H., Zamarian, L., Benke, T. (2007) Decision-making with explicit and stable rules in mild Alzheimer’s disease, Neuropsychologia, 45(8), pp. 1632-41.

Gleichgerrcht, E., Ibáñez, A., Roca, M., Torralva, T., Manes, F. (2010) Decision-making cognition in neurodegenerative diseases, Nat Rev Neurol, 6(11), pp. 611-23.

Ha, J., Kim, E.J., Lim, S., Shin, D.W., Kang, Y.J., Bae, S.M., Yoon, H.K., Oh, K.S. (2012) Altered risk-aversion and risk-taking behaviour in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, Psychogeriatrics, 12(3), pp. 151-8.

Hampton, A.N., O’Doherty, J.P. (2007) Decoding the neural substrates of reward-related decision making with functional MRI, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104(4), pp. 1377-82.

Hsu, M., Bhatt, M., Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., Camerer, C. F. (2005) Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making, Science, 310, pp. 1680–1683.

Kloeters, S., Bertoux, M., O’Callaghan, C., Hodges, J.R., Hornberger, M. (2013) Money for nothing – Atrophy correlates of gambling decision making in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, Neuroimage Clin, 2, pp. 263-72.

Manes, F., Torralva, T., Ibáñez, A., Roca, M., Bekinschtein, T., Gleichgerrcht, E. (2011) Decision-making in frontotemporal dementia: clinical, theoretical and legal implications, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 32(1), pp. 11-7.

Rahman, S., Sahakian, B.J., Hodges, J.R., Rogers, R.D., Robbins, T.W. (1999) Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia, Brain, 1999, 122 (Pt 8), pp. 1469-93.

Rosenbloom, M.H., Schmahmann, J.D., Price, B.H. (2012) The functional neuroanatomy of decision making, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 24(3), pp. 266-77.

Sinz, H., Zamarian, L., Benke, T., Wenning, G.K., Delazer, M. (2008) Impact of ambiguity and risk on decision making in mild Alzheimer’s disease, Neuropsychologia, 46(7), pp. 2043-55.

Weintraub, D., Siderowf, A. D., Potenza, M. N., Goveas, J., Morales, K. H., Duda, J. E., Moberg PJ, Stern MB. (2006) Association of dopamine agonist use with impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease, Archives of Neurology, 63, pp. 969–973.