In a crowded space, the Alzheimer’s Society and Dementia UK, two large dementia charities, effectively ‘compete’ as dementia charities. However, in the last few years, funding for the Alzheimer’s Society for initiatives such as ‘Dementia Friends’, costing millions, as a public-not profit partnership has helped to skew this space, such that the Alzheimer’s Society has commanded a relative advantage.

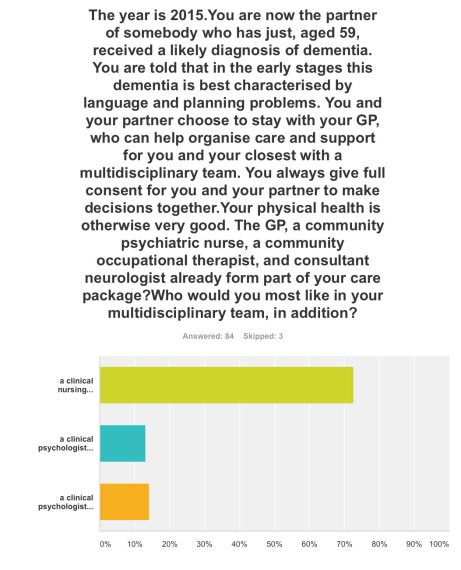

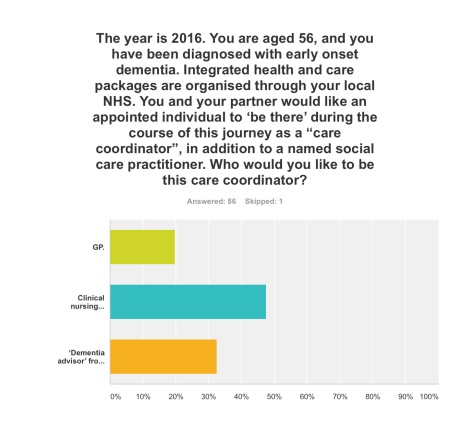

There has been criticism that the clinical nursing specialist approach of the ‘Admiral nurses’ is not an appropriate business model, but it is also true that specialist nursing has been repeatedly marginalised in policy documents in the last few years. It is however generally acknowledged that, despite a widely acknowledged problem in English policy in bridging the ‘diagnosis gap’ of undiagnosed people living with dementia, social care and post-diagnostic support for dementia has been on its knees due to savage cuts in social care spending.

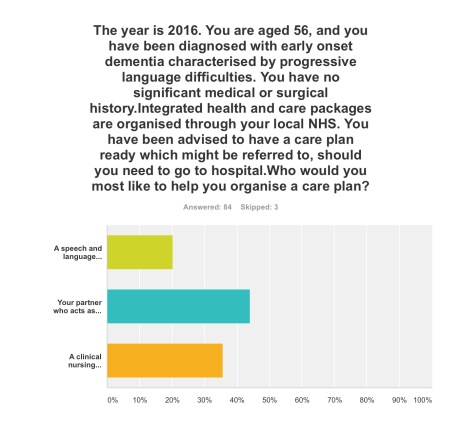

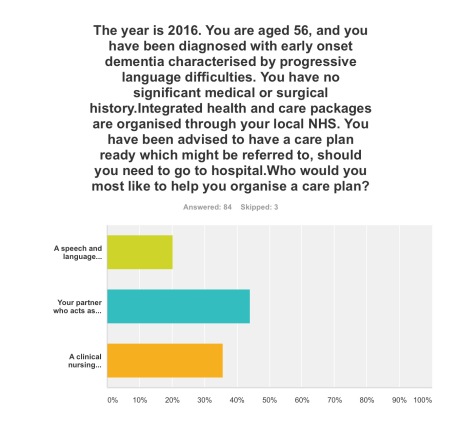

The clinical advantages of proactive case management of clinical nursing specialists have been widely rehearsed elsewhere. That is, despite a need for raising ‘awareness’ from people who are relatively underskilled themselves in dementia, there needs to be input from trained and skilled people in dementia. That the workforce in the NHS and care need to be skilled is widely accepted. As the demands for the acute medical services are likely to remain at fever pitch, it is a priority to keep admissions of people living with more advancing dementia, particularly those also living at frailty, at a minimum as such patients, particularly if unaccompanied by a caregiver, can do particularly badly in an acute admission due to the distress caused by an unfamiliar environment (amongst various reasons).

Politically, we are in a weird territory. It is felt that the most likely outcome of the UK general election to be held on May 7th 2015 will be a hung parliament, particularly if Scotland decides en masse to reject the Labour Party, and to vote for the Socialist National Party in majority. This has led to a former Tory chairman to argue, most recently, that a coalition pact between the Conservatives and Labour after the election may be the only way to keep the UK together if the Scottish Nationalist Party holds the balance of power at Westminster. There was formerly a grand Coalition during the Second World War.

That the Alzheimer’s Society and Dementia UK do different things in itself should not worry people in society at large, but the lack of plurality in this hugely important sector of dementia should. An overly dominant provider in any sector can lead to a dominant position where success begets success, and ‘Dementia Friends’ could be the shoo-horn in for services provided by the Alzheimer’s Society, even if this approach is vigorously denied or officially unintended by the Alzheimer’s Society. Whenever the media refer to dementia these days, it invariably is in the context of the Alzheimer’s Society not Dementia UK, and the Alzheimer’s Society, not Dementia UK, form the Secretariat of the All Party Parliamentary Group in dementia.

Charities could get 10-year contracts to help deliver NHS services if Labour wins the general election, according to Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, to an audience of voluntary sector leaders. Not-for-profit care organisations would be given “a form of preferred provider” status under legislation that a Labour government would introduce to replace parts of the coalition’s 2012 Health and Social Care Act (2012). The move would recognise their contribution to strengthening communities, and form part of the legislative agenda of a new Labour government, if elected. This appears to be intended by Labour give voluntary sector providers “longer and more stable arrangements” than for-profit contractors, but will concern NHS campaigners as further evidence of public sector resources being transferred to non-public recipients.

Addressing the health and social care conference of Acevo, the voluntary sector chief executives’ group, Andy Burnham is reported to have said: “The voluntary sector should have a different status in law when it comes to contracting, in terms of length of contract and the way contracts can be renewed without open tender.”

There is a growing recognition that all those involved in dementia care need a greater level of expertise in managing general health problems. Several cardiovascular disorders have been suggested as risk factors for dementia, such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation and heart failure; it is generally felt that correct management of these conditions can slow down cognitive decline, reduce the risk for dementia, and a clear focus has to be in future on the interplay of medications for such conditions.

Co-morbid conditions can overlap with each other during the management of treatment, further mandating a case for clinical nursing specialists in “proactive case management”. Patients and caregivers can experience difficulties with the therapies prescribed for each co-morbid condition, reducing adherence to the treatment plan and consequently diminishing its efficacy.

Innovative commissioning, through the “prime contractor” model encouraging plural stakeholders including the third sector, could have a constructive role here in meeting wellbeing outcomes for the National Health Service, which will be critical in the delivery of “whole person care”. (For an overview of the primary contractor model see the Department of Health (2013) document entitled “The NHS Standard Contract: a guide for clinical commissioners“.) There is also a coherent economic case for such proactive case management in the drive to avoid certain acute hospital admissions for people with dementia.

In Staffordshire, the plan currently is for four clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), NHS England and Public Health England are working with Macmillan Cancer Support, and with the support of two local authorities, to redesign cancer and end-of-life care services. They are in the process of co-designing new care pathways with patients and carers.

Under such an arrangement, care is to be managed and contracted through a single provider, which will be held accountable for the entire patient experience and clinical outcomes. Involvement of service users and carers is central in determining the outcomes for this contract. The “prime provider contracts” will replace around 70 separate sub-contracting arrangements. Providers will need to demonstrate they have achieved a pre-agreed set of quality measures within a given expenditure target.

Contracts will be for ten years. In the first two years, the CCGs and Macmillan will support the selected prime providers to improve the currently available data on activity and costs. It is very difficult to deny that the impact of Macmillan specialist nurses has been a beneficial one, and has revolutionised post diagnostic service support and care for the cancers.

Aa key element of the prime provider’s work in the first two years will be to improve the data and analytics in order to provide a basis for a truly outcomes-based contract. They will also be expected to demonstrate real improvement in patient and carer experience.

Patient safety and patient experience are pivotal for the NHS Outcomes Framework. The aim of the NHS is not only to add years to life, but to add life to years. One could argue that the roles of raising awareness and ‘advising’ are important but complementary to highly specialist nursing support. Such specialist nursing support could work in tandem with specialist social practitioner input, as it is acknowledged that liberty and safeguarding issues are especially important for some patients in later stages of dementia in whatever care setting.

A grand coalition of more than provider, such as the Alzheimer’s Society or Dementia UK, and in social care, may be “unthinkable”, but perhaps has to be put on the agenda, especially if serious moves afoot to deliver whole person care are to become a reality. They would need to have meticulous governance arrangements in place. As a comparison, while ‘Manc dev’ arguably gives some financial stability and some breathing space for innovative integration of health and care to flourish, there is an apt concern that the proper mechanisms are not in place if anything goes wrong.

For dementia post-diagnostic support to ‘crash’ due to improper governance of funds would indeed be the unthinkable.