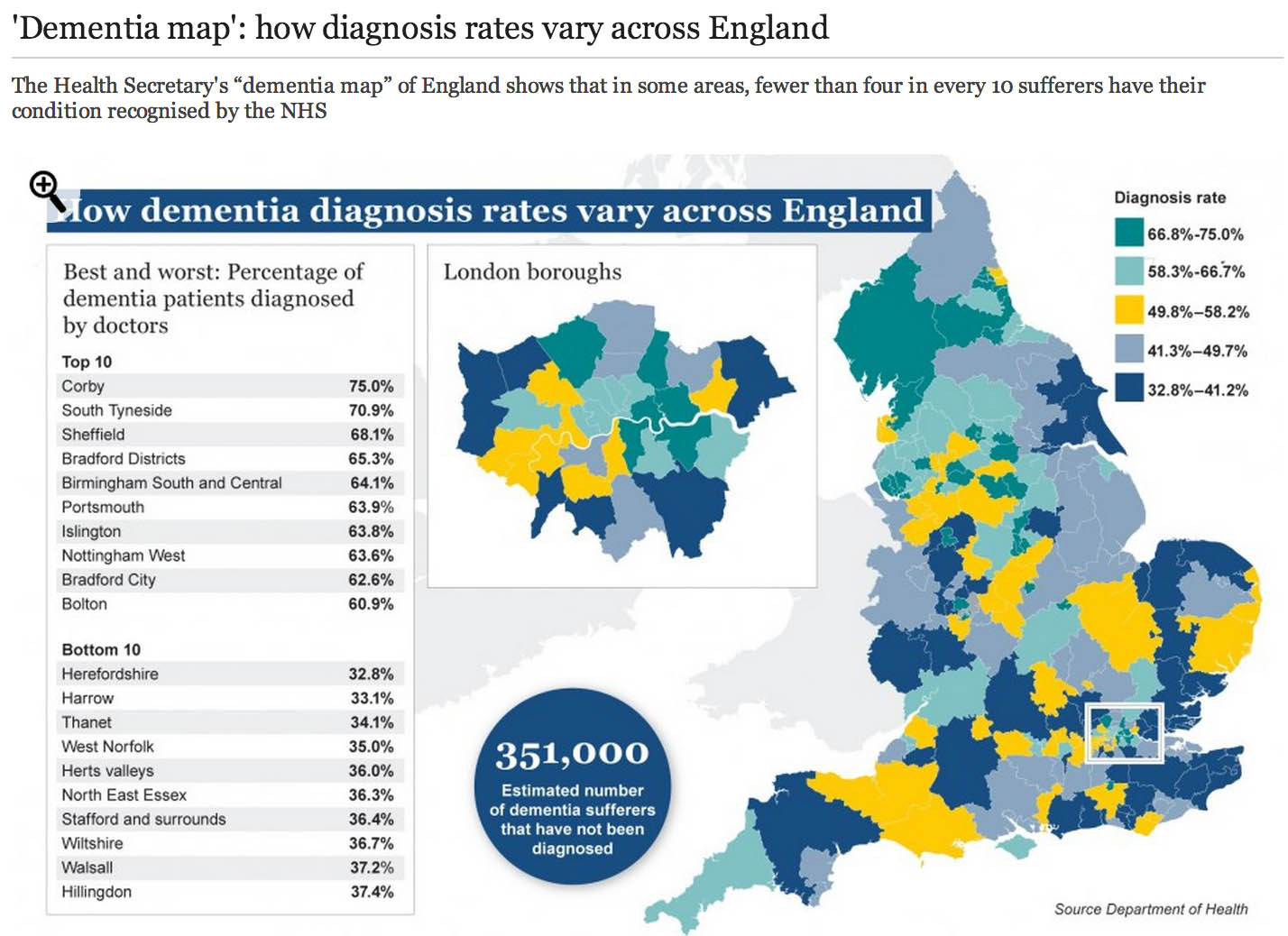

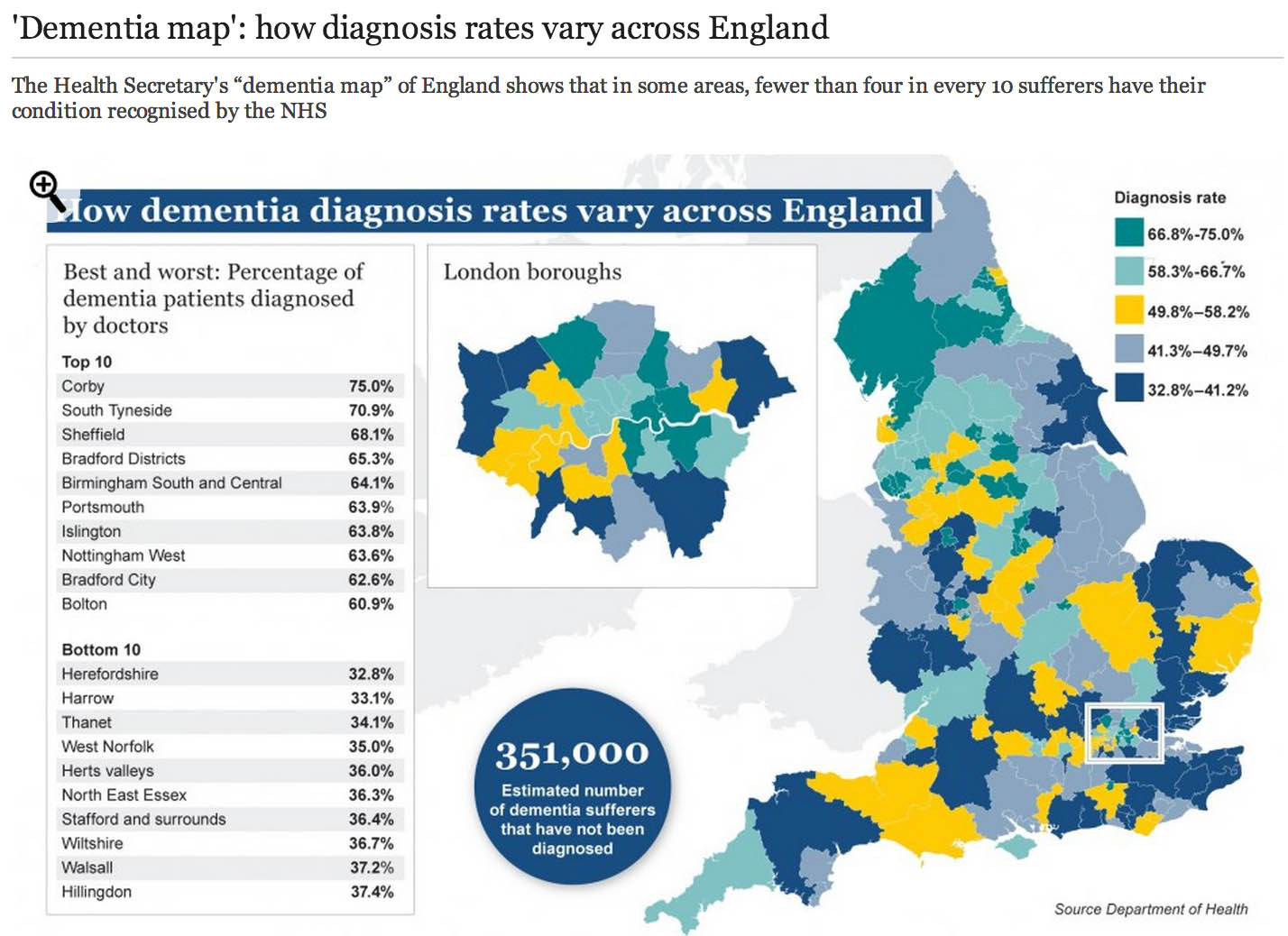

The market philosophy has gripped the NHS by the jugular through policy developments from successive governments. It is argued that all health care systems in the world have to design effective allocative mechanisms for the available “scarce health care resources”. The “dementia prevalence calculator” tool also enables health and care communities to: calculate local dementia diagnosis rates, forecast local dementia prevalence, view trajectories and set “ambitions” (aka targets) for improvement in diagnosis rates and compare diagnosis rates with other localities. Its main problem has been that it has been crowbarred in through various side windows, except nobody knows why public health experts didn’t call for this calculator to come in through a front door. One can now view and compare diagnosis rates on the “Ambition Map”, and link to the “Knowledge Portal” to access a wealth of resources to improve dementia diagnosis rates, and diagnosis pathways. All of this will have taken time, effort and money to set up, so the question of whether it’s worth it, given ‘scarce resources’, is clearly in the public interest. Here is one such example of the Department of Health’s attempts and their partners to disseminate information about “the dementia map”.

So what’s the point of these data? Burns concedes that estimating the number of people who have dementia is important for both local planning and national guidance. Burns freely admits too there have been problems in the past:

“Most current estimates of dementia prevalence (the number of people affected by the disorder) and incidence (the number of people developing it over a defined period, usually one year) are based on studies dating back to the 1980s.”

It’s become clear that a huge “democratic deficit” has engulfed the English dementia policy. The problem for Prof Alistair Burns, who is a genuinely a nice and well-meaning man, is that he can become indundated with various complaints from academics and practitioners. An example is the G8 dementia summit which was presented as a ‘once in a lifetime opportunity’ to talk about dementia. What did, however, happen was that it became a ‘once in a lifetime opportunity’ for various myths to be propagated by the media, using highly charged words such as ‘shocking’, ‘devestating’, ‘crippling’, ‘horrible’, ‘horrific’, portraying the notion that people now on receiving a diagnosis of dementia are just counting their hours until their death. It, likewise, cannot be overstated that the drugs for memory or attention simply do not have a huge effect in the vast majority of patients, and certainly after about fifteen years of published studies on these “cholinesterase inhibitors”, the evidence that they slow down the rate of loss in critical parts of the brain is not terrific. Academics in dementia are currently collaborating across geographical boundaries, so the idea of there now being suddenly a world collaboration is FALSE. A cure for a single dementia is FALSE as there are hundreds of different causes of dementia. Dementia charities of course can mobilise individuals with dementia to contribute in pan-global drug trials in what has been euphemistically been called ‘co-production’, discovering new drugs based on the basis of personal DNA genomic information. Looking at your genetic make-up might tell a practitioner or drug-company your risk of subsequently developing dementia, and so it goes on. The issue is not subjecting the designers of English dementia policy with time-consuming vexatious ‘attacks'; it is hopefully that we can all have an open, transparent discussion of some of the ‘unintended consequences’ of the English dementia policy currently in progress.

In March 2012 the Prime Minister, David Cameron, published his challenge on dementia which set out an ambitious programme of work to push further and faster in delivering major improvements in dementia care and research by 2015, building on the National Dementia Strategy (published on 3 February 2009). Central to the challenge is the requirement that from April 2013, there needs to be a quantified ambition for diagnosis rates across the country, underpinned by robust and affordable local plans (NHS Mandate). This is of course so remarkable in itself in the State having such a strangehold on policy which should in theory be devolved as locally as possible to experts and professionals. A painfully obvious point to those who have done a medical degree is that there will be variation in some rates of particular dementias across the country anyway. For example, in some populations with a predominantly Asian immigrant population with certain risk factors, they might be at high risk of vascular dementias. As it happens, near Warsaw in Poland is thought to have a high prevalence of dementia due to copper overload due to a genetic cluster of an inherited copper metabolism problem called Wilson’s disease. But presumably certain dementia charities and certain politicians want you ‘to get angry’ at those GPs who are underdiagnosing dementia, because they are somehow colluding in keeping this information away from you. This is by the way against their professional code, but you cannot expect people without a medical background who are quite senior in charities or politics to know that necessarily.

I have found that having lack of ability to have a balanced debate (due to enormous information asymmetries) has been quite dispiriting, and clearly hampered by the virtual lack of published research papers in the medical professional literature. Hopefully, the University of Stirling will be able to diminish this ‘research gap’, now that they have been awarded a major grant to investigate this issue properly with no vested interests. This is the only paper on Medline from 1996 if you search for the term “dementia prevalence calculator”. And there is no doubt that the claims of some of the drugs used to treat early dementia in the NHS have been overinflated. Luckily, largely thanks to the work of Glenis Willmott MEP who has been leading negotiations as the European Parliament’s rapporteur on the clinical trials regulation, pharmaceutical companies and academic researchers will be obliged to upload the results of all their European clinical trials to a publicly accessible database, if a deal reached this week is approved, according to a recent report. Indeed, Pharma have got it right about “openness”, but not in the sense of using regulation to allay fears about patient privacy and confidentiality – Big Pharma need to share with the general public their results, and their particular motives and intentions for dementia policy especially if the descriptions are otherwise not easily forthcoming.

I openly admit to being extremely disappointed at one particular plank of English dementia policy: the “dementia prevalence calculator”. It’s incredibly easy to get hold of the marketing shills for CCGs about how they can overcome “the diagnosis gap” for the reported lack of diagnosis of dementia; but there again, the discussion of how there are hundreds of different types of dementia in different age groups is not forthcoming, together with a less than candid explanation of how risk factors for dementia might be tackled. For something so fundamental to English dementia policy, it was deeply distressing to see Prof Carol Brayne’s question on where the Prime Minister saw his “Challenge” progressing on dementia to be passed ‘down the line’ like a rugby ball going backwards with effortless ease first to Mr Jeremy Hunt and then with Dr Margaret Chan. To get a decent grasp on why there has been such a drive to improve dementia rates, you have to go across the Atlantic and research terms such as “needs based resource allocations” in health maintenance organizations (sic). These papers are written entirely from the business model perspective, so do not have any intention of wishing to address remotely the professional concerns of senior clinicians in dementia.

Like all 500 pages of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), there was no open discussion of the need to “turbo boost” the outsourcing of NHS contracts to the private sector. Likewise, meaningful discussion of the perils of ‘case finding’ and ‘screening’ in dementia have largely been throttled at source (though Dr Martin Brunet has been raising awareness of the perils of incentivising GPs to up their rates of dementia diagnosis through ‘case finding’ in primary care, of course drawing attention to the hugely stigmatising “false diagnoses of dementia”). Nonetheless, through the combined efforts of the European ALCOVE project (including Prof Burns and Dr Karim Saad), it’s been successfully argued that,

“Dementia happens to people, living in their families and their communities. It does not happen just to their brains. When people have worrying symptoms they want health care professionals who can spot the signs, take their concerns seriously, diagnose the problem accurately, so they can get the most up to date treatment and advice.”

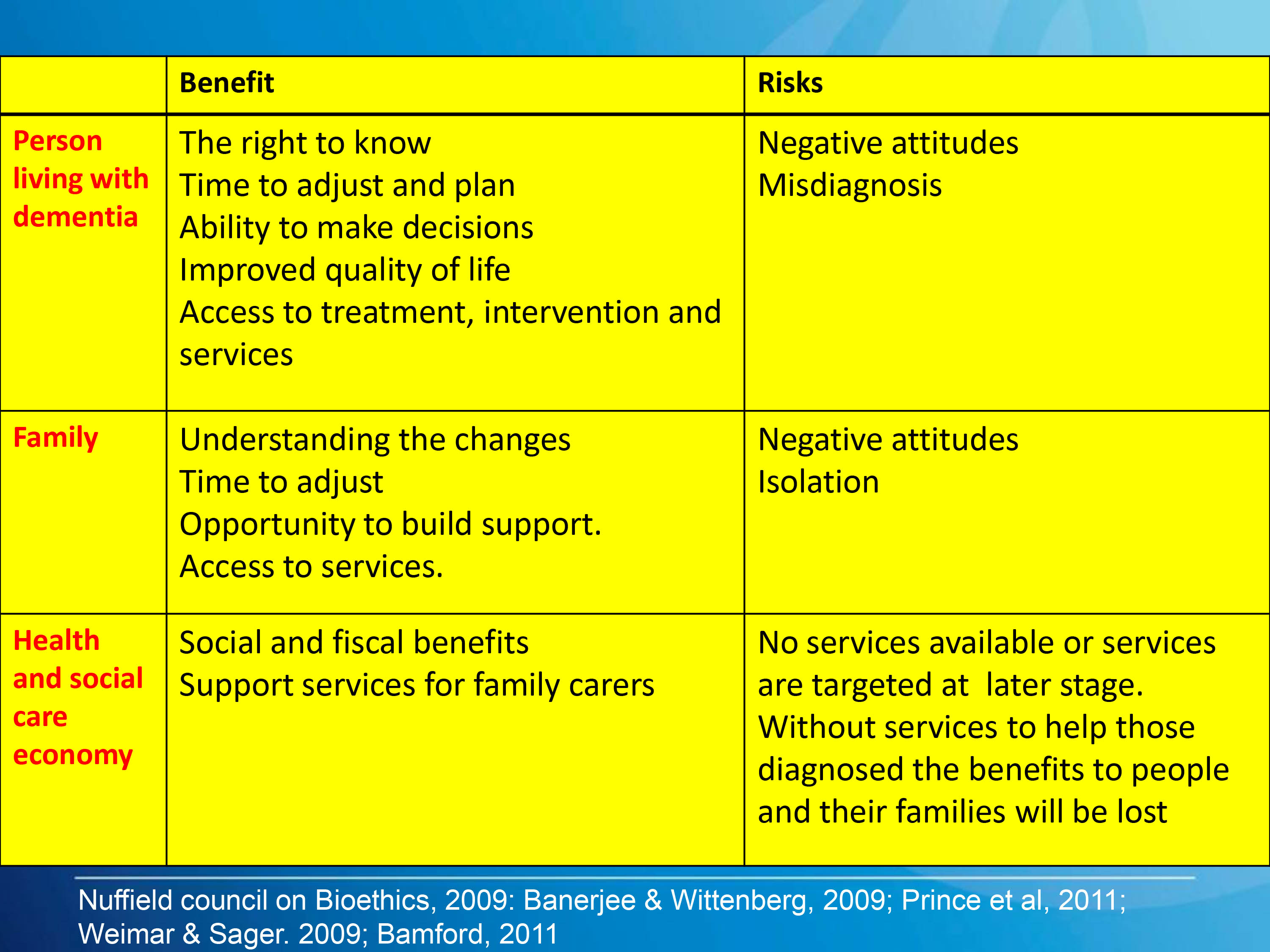

This is a helpful slide from Prof Dawn Brooker’s presentation for the UK Dementia Congress Conference 2013 entitled, “Benchmarking against ALCOVE recommendations for timely diagnosis in dementia”:

This discussion embarrassingly even led to Prof Burns trying to find Dr Brunet at his practice for a frank chat about the policy, but Martin unfortunately was away that day.

Of course, if you’re going to introduce a policy to ‘up the dementia rate’, it possibly will run into problems given that the actual prevalence of dementia has appeared to be falling. The first UK Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (CFAS), known as the Medical Research Council (MRC) CFAS, began in 1989. One of a suite of European prevalence and incidence studies (forming the EURODEM collaboration), it was designed to test for geographical differences within the UK, across populations with widely varying characteristics, including vascular health. The study published by Matthews and colleagues (2013) in the Lancet confirmed that later-born populations have a lower risk of prevalent dementia than those born earlier in the past century. The general prevalence of dementia (overall numbers of people) in the population might be subject to change. Factors that might increase prevalence include: rising prevalence of risk factors, such as physical inactivity, obesity, and diabetes; increasing numbers of individuals living beyond 80 years with a shift in distribution of age at death; persistent inequalities in health across the lifecourse; and increased survival after stroke and with heart disease. By contrast, factors that might decrease prevalence include successful primary prevention of heart disease, accounting for half the substantial decrease in vascular mortality, and increased early life education, which is associated with reduced risk of dementia. Where possibly primary care will have the greatest impact will be in tackling the risk factors they do anyway for cardiovascular disease, i.e. better diabetic control, tackling cholesterol, smoking, ‘poor diet’, or high blood pressure. This in itself is not a valid reason to avoid improving diagnosis rates of dementia (especially these are treatable risk factors for vascular dementias.)

Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) have been argued by their supporters as a “cost-effective’ way to provide health care. In the United States, in allocating resources in the HMO, the rationing of preventive services appears to be one of the principal questions where the potential benefits (i. e., efficacy) of a service are considered in relation to costs of healthcare. The direct counterpart of the HMO in English health policy, following the enactment of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), is the “clinical commissioning group”, which act as state insurance schemes for pooling risk in population samples.

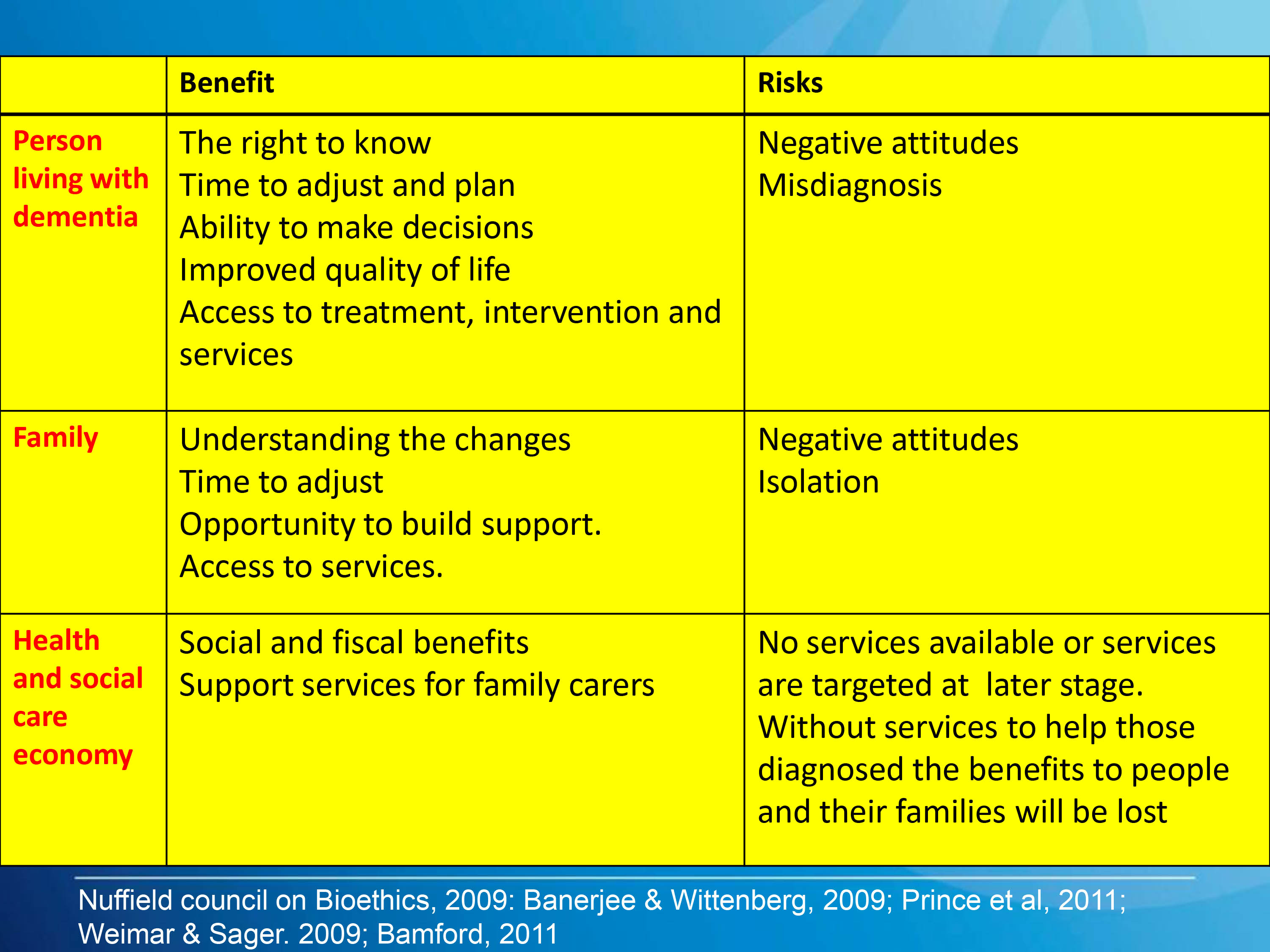

Just because there’s no effective treatment, there’s still a business case to be made for ‘opening up new markets’ of persons with dementia. For example in the NHS Outcomes Framework 2013/4 domain CB_A9 covers an estimated diagnosis rate for people with dementia, with an aim of “improving the ability of people living with dementia to cope with symptoms, and access treatment, care and support.“. The rationale is therefore stated as:

“A diagnosis enables people living with dementia, and their carers/families to access treatment, care and support, and to plan in advance in order to cope with the impact of the disease. A diagnosis enables primary and secondary health and care services to anticipate needs, and with people living with dementia, plan and deliver personalised care plans and integrated services, thereby improving outcomes.”

According to articulation of neo-liberal ideology, the main justification of the reforms is to make resource allocation “more efficient, more innovative and more responsive to consumers’ preferences” than centrally integrated health systems (Ven 1996, p. 655). The effect of this change in philosophy is the introduction of activity-based resource allocation and funding as a system of paying hospitals and other health care providers on the basis of the work they perform rather than previously applied defined budgets based en bloc global contractual considerations. This new system relies on cost-and-volume and cost-per-case contractual relationships, in which payments are closely linked with the services offered, and clearly the information from “dementia prevalence calculators” is useful here. Conceptually, “dementia prevalence calculators” have been presented on equity grounds, i.e. tackling the inequity of a postcode-lottery diagnosis of dementia. However, this makes a fundamental assumption that there cannot be geographical variations in the prevalence of dementia. I repeat the point – any practising physician would know that this assumption is entirely erroneous, as vascular dementia prevalence rates for cardiopaths for diabetic hypertensive individuals in Tower Hamlets in a ghee-laden diet might be hypothesised to be quite high? The actual drive for the ‘dementia prevalence calculator’ is to open up new active markets, in a form of ‘payment of results’. According to Gay and Kronedfeld (1990), the gradual evolvement of an activity based resource allocation can be traced to the United States, where from 1983 most reimbursement for health care providers had been based upon the Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) where patients within different categories were classified as clinically similar and were expected to use the same level of hospital resources.

Having a ‘care plan’ for dementia is potentially advantageous in that it can provide harmonisation with private insurance systems. The ‘Kaiser Permanente Care Management’ program contains guidelines and recommendations on how dementia care should be provided to Kaiser enrollees. The new program is an informational resource only and is not a substitute for clinical judgment based on the individual needs of patients. The program includes nine “key principles” on diagnosing and caring for patients with dementia and support for their caregivers. These principles include early identification and diagnosis, connecting caregivers to vital community resources, developing a care plan, and monitoring and adjusting medication use. With the introduction of “whole person care” (or similar models of integrated care in the next government), it is likely health and social care will be taken down a “final common pathway” of the ‘personal budget’ or ‘individualised’ budget (see this article for a recent discussion of some of the key themes from the English healthcare thinktanks). The commercialisation of care, under the guise of control and budgets, is, in fact, of course a complete anethema to genuine principles of professional person-centred care. And merging a universal system which has lots of highly personal data (NHS) with one that is heavily conditional (benefits) has all kinds of risks. In the long run it could make it still easier to restrict access to healthcare on the basis of economic status or behaviour.

While GPs and the public are clearly none-the-wiser about the goal of upping the diagnosis rates, already work is being done on the barriers and solutions for implementation of personal health budgets in dementia. Claire Goodchild’s report for the Mental Health Foundation from October 2011 still makes for interesting reading. Goodchild argues that, “individualised, tailored support and care that a personal budget can facilitate can have enormous benefits to a person with dementia“. The irony is of course that Big Pharma may not actually end up the big beneficiaries of this drive, unless they can make their medications relevant to individuals with dementia in this brave new world. While the G8 conference was an effective pitch for personalised medicines for Big Pharma, relatively little attention was given to psychological therapies or carers, aside from ‘dementia friendly communities’ which bring competitive advantage to the included corporates (and benefits for persons with dementia too). Personal budgets are all about choice and control; it is unlikely that a person with dementia will be unaware of the personal spending decisions that he or she can make to improve wellbeing (deferred to a carer where that person does not have capacity); but other valid interventions do include the assistive technologies and innovations which curiously did also make a mention in the G8 dementia.

Therefore, at first blush, it might look a bit random having a ‘dementia prevalence calculator’ and then all the shennanigans of the G8 dementia summit, but whilst the English government cannot as such make dementia ‘wealth creating’, it can do its best to open up new markets. It hasn’t been an accident that the question, “Have you had problems with your memory?”, has been suggested for those ‘health MOTs‘ which private healthcare would love to get off the ground. And the big beauty of this plan when NHS budgets are looking to do ‘more with less’ or implement ‘efficiency savings’ (or cuts to frontline care, more accurately) is that the NHS budget itself won’t ‘take the hit‘. It is hoped that with the implementation of whole person care budgets somebody will be able to ‘top up’ payments for care (e.g. “co-payments”), and the patient (or customer) will now pay for care providers in the private sector too. Do the treatments actually have to be proven to work? Absolutely not, if the experience in personal health budgets is anything to go by, but that’s not the point. As David Cameron might say, “Oh come on.. please do keep up!”

Further reading

Gay E.G. and Kronedfeld J.J. (1990). “Regulation, retrenchment – the DRG experience: problems from changing reimbursement practice”. Social Science and Medicine. 31 (10), pp. 1103-1118.

Ven, W.P.M.M., van de. (1996). “Market-oriented health care reforms: trends and future options”. Social Science and Medicine. 43 (5), pp. 655-666.