In case you don’t like the soundtrack, here are the slides.

To some extent, Europe resolved our dispute about whether we should aspire to an ‘early diagnosis’, or ‘timely diagnosis’ for dementia. The overall consensus from the European ALCOVE project was that a diagnosis should be timely, in keeping with the needs of the person with a dementia, his friends, his family or his carers.

This was an extremely helpful move in English policy, although the road had not been that clear.

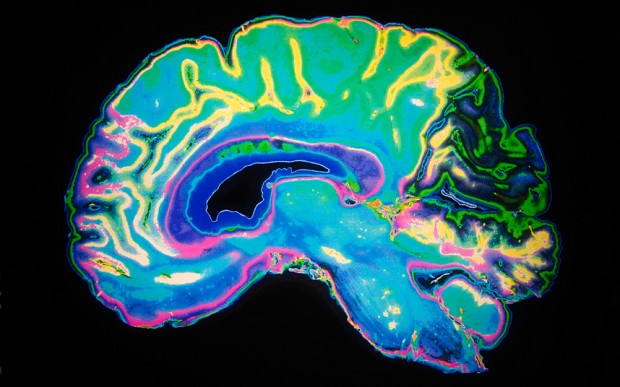

One blurred line in the public was how dementia so massively became conflated with all memory problems in the elderly. Whilst it was argued that the memory problems in Alzheimer’s disease should no longer be passed off as ageing (and indeed there are strong cultural pressures elsewhere for calling dementia ageing), there was some concern from GPs that older people thought their memory problems were dementia because of the widespread media campaign. Many of these individuals were later to arrive at a diagnosis of minor cognitive impairment, underactive thyroid, or depression. Given that there are hundreds of different causes of dementia which can affect any part of the brain and brainstem (though they all tend to start off in different areas), it’s not altogether surprising that some of the dementias don’t present with memory problems at all.

The drive to make the diagnosis is almost certainly going to be affected by the policy from NHS England to achieve ‘ambitions’ for increasing dementia diagnosis rates. The evidence from the MRC study at Cambridge has demonstrated that this prevalence has in fact been falling over some decades, so there is serious concern that a drive to increase dementia rates will lead to a large number of false diagnoses in 2014. This is definitely one to watch, as a false diagnosis can lead to very serious harmful repercussions. Nonetheless, the number of people who have a MMSE in the region of 10-15 on initial diagnosis is, arguably, staggering, and blatant lack of diagnoses of more obvious presentations of diagnosis most people would agree is unacceptable.

The spotlight in G8, and certainly the presence of corporates there, will lead to increased scrutiny of those people who financially have much to gain from an early diagnosis. An early diagnosis may indeed lead to someone ‘accessing care’, even that care results from a personal health budget with treatments which are not proven clinically from the evidence. The direction of this particular plan depends how far individualised consumer choice is pushed in the name of personalisation. Genetics, neuropsychologists, and pharmaceutical private sector companies wishing to monitor the modest effects of their drugs on substances in the brain all stand to capitalise on dementia in 2014, much of which out of the NHS tax-funded budget. This of course is privatisation of the NHS dementia policy in all but name. One thing this Government has learnt though is how to make a privatisation of health policy appear popular.

Despite corners being cut, and the drive to do ‘more for less’, it will be quite impossible to avoid making a correct diagnosis in individuals thought to have a dementia in the right hands. A full work-up, though the dementia of the Alzheimer type, is the most common necessitates a history of the individual, a history from a friend, an examination (e.g. twitching could be associated with the motor neurone disease variant found in one of the frontotemporal dementias), brain scan (CT/MRI/PET), brain waves (EEG), brain fluid (cerebrospinal fluid), bedside psychology, formal cognitive psychological assessment, and even in some rarely a brain biopsy (for example for variant Creutzfeld-Jacob or a cerebral inflammatory vasculitis).

Analysis by paralysis is clearly not desirable either, but the sticking point, and a blurred line, is how England wishes to combine increasing diagnostic rates; and making resources available for post-diagnosis support; making resources available for the diagnosis process itself including counselling if advised. As the name itself ‘dementia’ changes to ‘neurocognitive impairment’ under the diagnostic manual DSM in 2015, the number of people ‘with the label’ is likely to increase, and this will be ‘good news’ for people who can capitalise on dementia. The label itself ‘neurocognitive impairment’ itself introduces a level of blur to the diagnosis of dementia itself.

The general direction of travel has been an acceleration of privatisation of dementia efforts, but this to be fair is entirely in keeping with the general direction of the Health and Social Care Act (2012). A major question for 2014 is whether this horse has now truly bolted?