LIVING BETTER WITH DEMENTIA: CHAMPIONS FOR THE FUTURE

‘Building on the National Dementia Strategy: Change, progress and priorities’ advances policy areas to improve diagnosis and post diagnosis support, commissioning of services, and ensuring a skilled dementia workforce.

REVISED CONTENTS TO ALIGN WITH ALL PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUP REPORT ON DEMENTIA PUBLISHED JUNE 18TH 2014

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The recent history of the English dementia strategy

Global dementia strategies and their communication.

Organisations, innovation and leadership.

The nature of ‘champions’.

Networks.

Physical needs of people living well with dementia.

Social determinants, autonomy and the whole person.

Exploring the mind to promote living well.

The three themes of the All Party Parliamentary Group 2014 report on dementia.

THEME 1: SUPPORT FOR PEOPLE WITH DEMENTIA FOLLOWING DIAGNOSIS

CHAPTER 2

Framing the narrative for living well with dementia

The effect of language in the media on living better with dementia.

Cultural metaphors: war, tides and fights.

Do people living with dementia “suffer”?

Questionnaire study of perception and identity: the #G8dementia summit.

Medicalisation, Alzheimerisation and living well with dementia.

Problems with the “dementia friendly communities” concept.

CHAPTER 3

Thinking globally about living well with dementia

Examples of various initiatives domestically and internationally.

Global trends.

The Prime Minister’s Dementia Strategy and the G8 Dementia Summit

The English Dementia Strategy compared to other dementia strategies

People with dementia as a social movement: Ruth Bartlett

Integrating people with dementia into national policies: Dementia Alliance International.

CHAPTER 4

Culture and living well with dementia

The diagnosis gap.

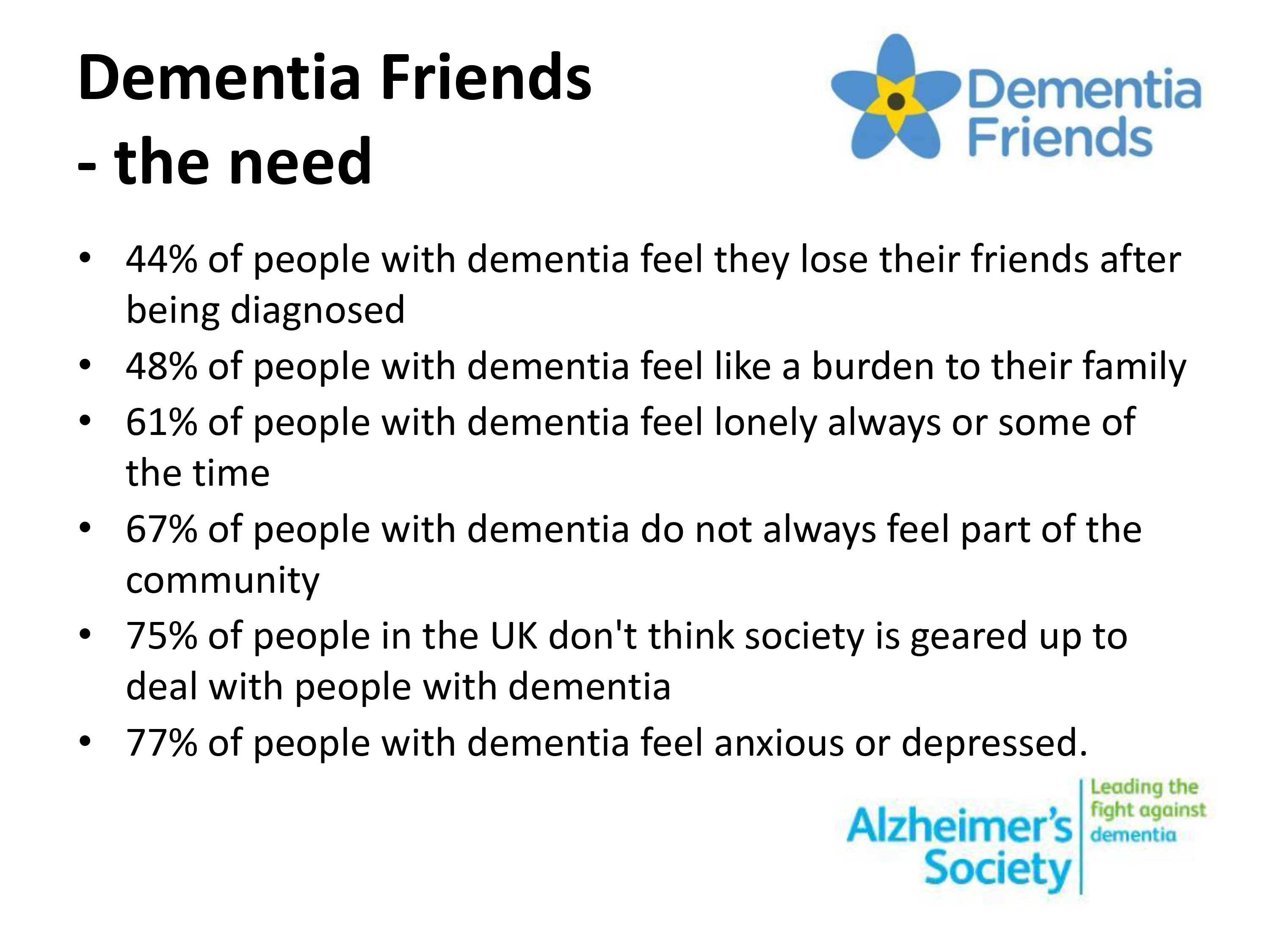

Stigma and discrimination.

Effect on diagnosis.

Prevalence studies in England and Australia.

Specialist groups e.g. LBGT, travellers, racial groups (such as BME, Latino and Asian populations), persons with learning difficulties.

Japanese “befriending”.

CHAPTER 5

Young onset dementia and living well with dementia

This chapter is likely to include a focused look on the changing needs of the early onset dementia/young onset group.

It is also likely to include the drive for genetic risk factors identification and whether this is likely to help policy or not.

Current state of play in the genetics of the ‘tauopathies’ in dementia of the Alzheimer type and frontotemporal dementia.

“Stopping dementia in its tracks”

Personalised medicine, genomics and data sharing.

Raising awareness of young onset dementia.

CHAPTER 6

Delirium and dementia: are they living well together in policy?

There is currently a slight confusion how cases are found in secondary care in delirium which inform on case finding in dementia.

Co-morbidity.

An analysis will be presented on a relative lack of interest in assessing an effect of timely interventions to promote living well with dementia, and how this has unwittingly distorted the screening debate for dementia based upon the Wilson and Jungner (1967) criteria.

Post-diagnostic support in delirium.

CHAPTER 7

Care and support networks for people living with dementia

The conflict between the sick role and living well with dementia

Are the terms “care” and “support” appropriate?

Dementia Action Alliance: Call to Action.

Shared purpose in dementia person-centred care: principles of shared care.

‘Triangle of care’ and RCN guidelines.

Alzheimer’s Australia report on acute dementia care in hospitals.

Relationship-centred care.

Institutional and inclusive approaches to care.

Carers and living well with dementia – tip of an iceberg?

Carers and unpaid family caregivers.

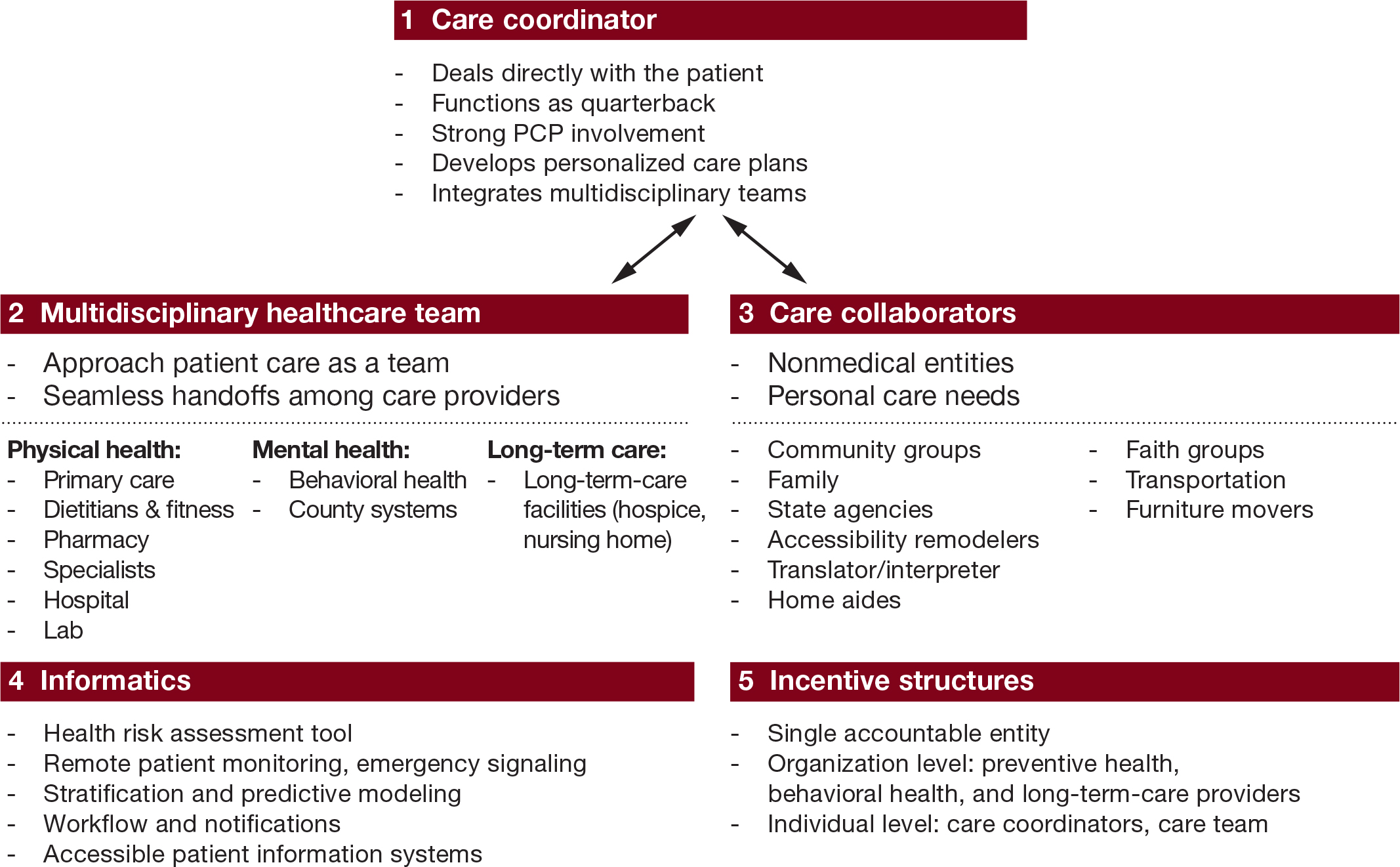

Community care coordinators: Essex/JRF work.

The anticipated demographics of unpaid family caregivers.

Signposting carers to appropriate services.

Evaluating quality of care in care homes (“the ENRICH project”).

Intermediate care.

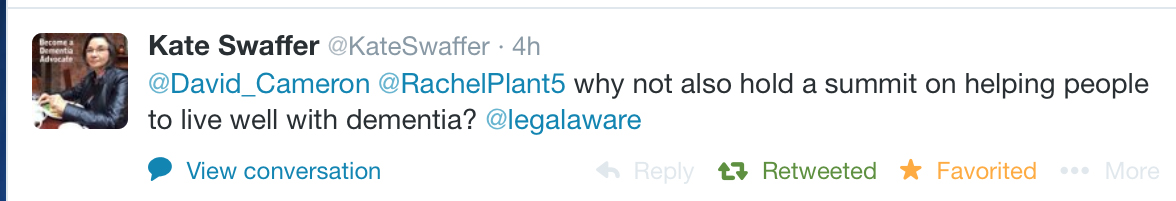

Kate Swaffer’s “prescribed disengagement model”.

Introduction to the rôle of dementia specialist nurses, including Admiral Nurses [this topic is resumed later in the book chapter on performance management.]

Is it possible to be suffering and living well with dementia simultaneously?

Manifestations of failure of communication with patients with more advanced dementias.

CHAPTER 8

Nutrition and living well with dementia

Dementia care pathway.

How to support a patient with dementia on the ward.

Self-reflection.

The design of eating environment.

Nutrition champions.

Difference between audit and research.

Royal College of Psychiatrists Dementia Audit.

“Food First”.

Disseminating research and audit findings.

CHAPTER 9

Incontinence and living well with dementia

Stress and urge incontinence.

Incontinence in different types of dementia.

Incontinence and medications.

Non-surgical approaches for incontinence.

THEME 2: COMMISSIONING HIGH QUALITY DEMENTIA SERVICES

CHAPTER 10

Seeing the whole person in living well with dementia

Integrating people living with dementia into policy formation: “co-production”

“Proactive” primary care.

Going from a philosophy of ‘risk mitigation’ to ‘living well’.

Whole person care and living better with dementia.

Social determinants of health

System innovations.

Oldham Commission report on “whole person care”.

Philosophy of integrated care.

Frailty and ‘front door’ approaches.

Principles of “Transforming primary care”.

Avoiding hospital admissions.

Social prescribing

CHAPTER 11

Why does housing matter for living well with dementia?

Design of housing and adaptations.

Supportive housing.

The structure and function of the English housing sector.

CHAPTER 12

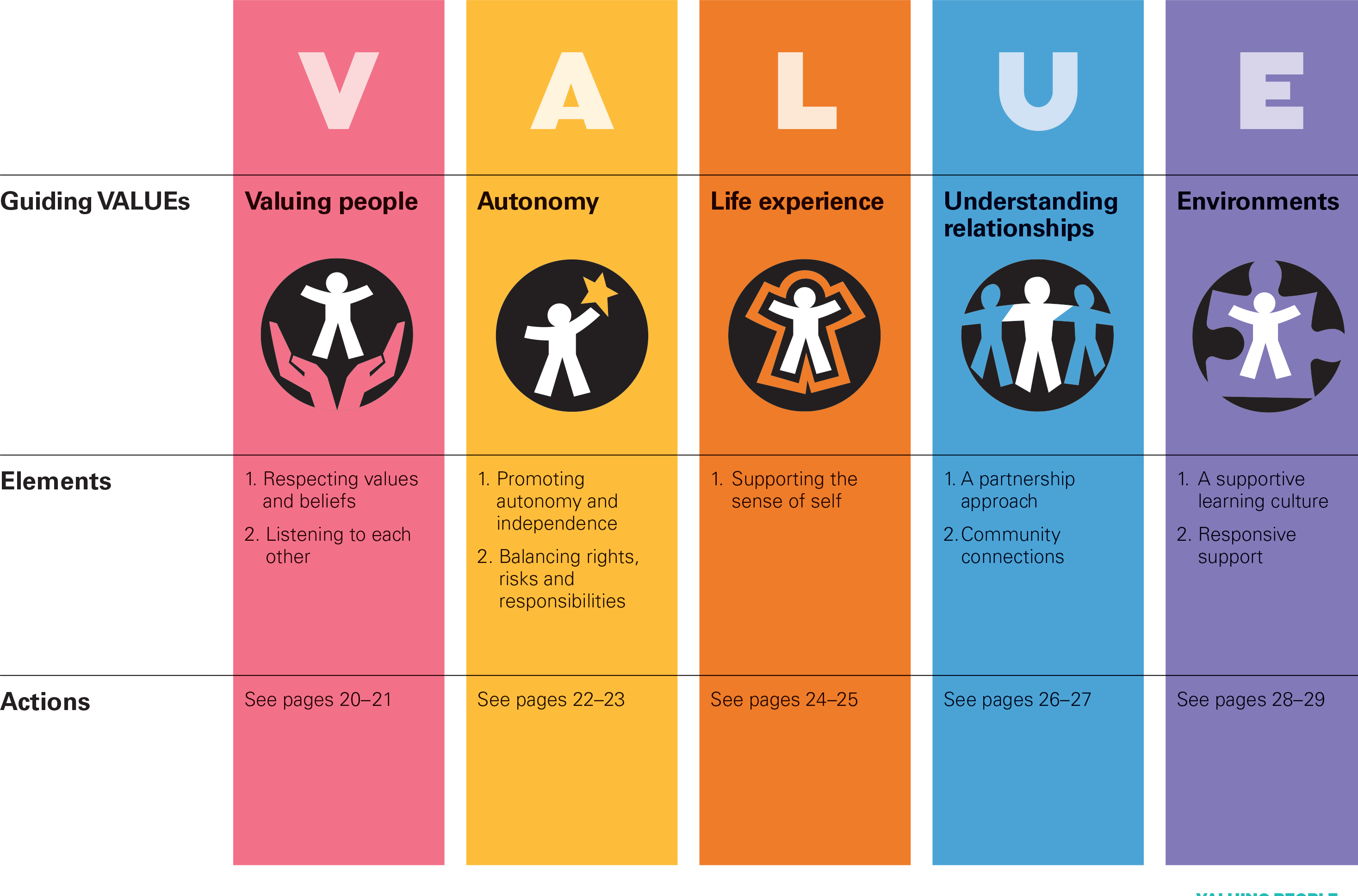

Introduction to autonomy and living well with dementia

The legal doctrine of proportionality.

Introduction to autonomy.

General principles of safeguarding.

Safety.

Human rights, liberty and the law.

“Smart” technology.

CHAPTER 13

Can living well with dementia with personal budgets work?

Personalisation and social care.

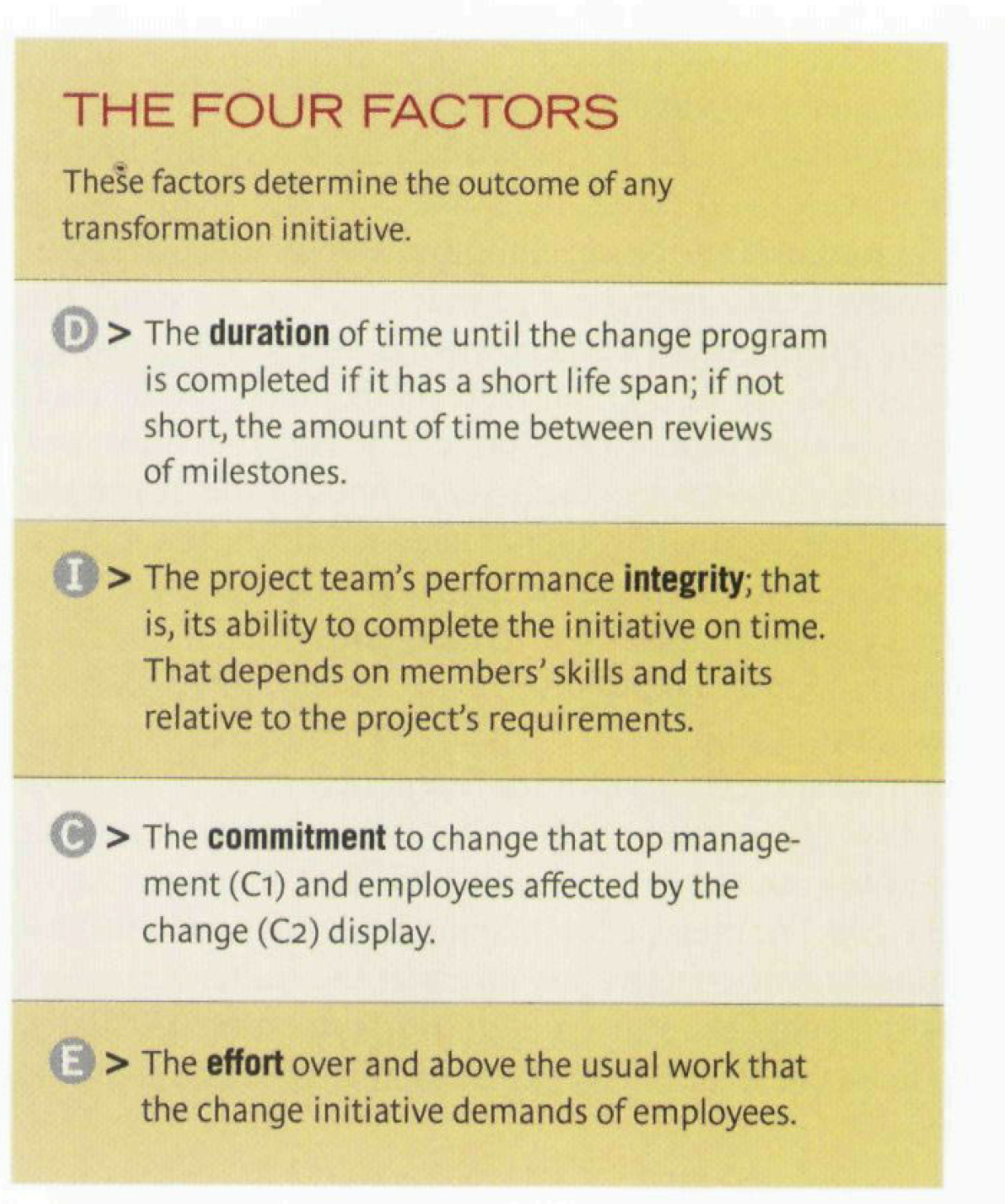

Cascading cultural change: “dementia champions”.

Schein’s model.

Personal budgets and living well with dementia.

History of this policy theme.

Implications for choice and control.

Implications for advocacy.

CHAPTER 14

Art and creativity in living well with dementia

Emergence of creative talent in dementia.

Theatre trips in dementia.

Singing and the brain.

Drama and living well with dementia.

‘Humour therapy’.

Animal/pet therapy.

Dance therapy.

CHAPTER 15

Reactivating memories and implications for living well with dementia

The application of neuroscience to understanding reminiscence in dementia.

Health needs of football fans.

The cognitive neurology of “sporting memories” and living well with dementia.

There is a temptation not to take sporting memories and reminiscence techniques not very seriously, as they are currently poor understood.

This chapter will review the evolution of the “sporting memories” initiatives, and consider how they might have a powerful neuroscientific substrate in memory systems after all.

Singing and playlists – towards a common neural substrate for reminiscence?

Metaphors for explaining dementia: the bookcase analogy.

THEME 3: DEVELOPING A SKILLED AND EFFECTIVE WORKFORCE

CHAPTER 16

Innovation and performance management in the workforce

Specialist nurses.

Training requirements for primary care and specialist nurses.

Training requirements for other allied health professionals.

Networks and innovation.

The importance of collaboration and innovation in securing competitive advantage

.

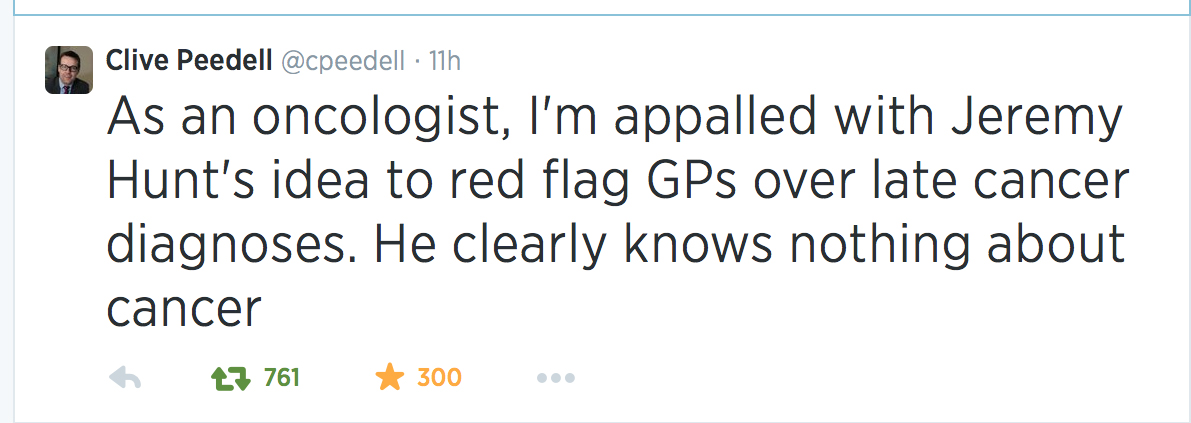

Social media and mitigation against loneliness.

Cultural change: Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN).

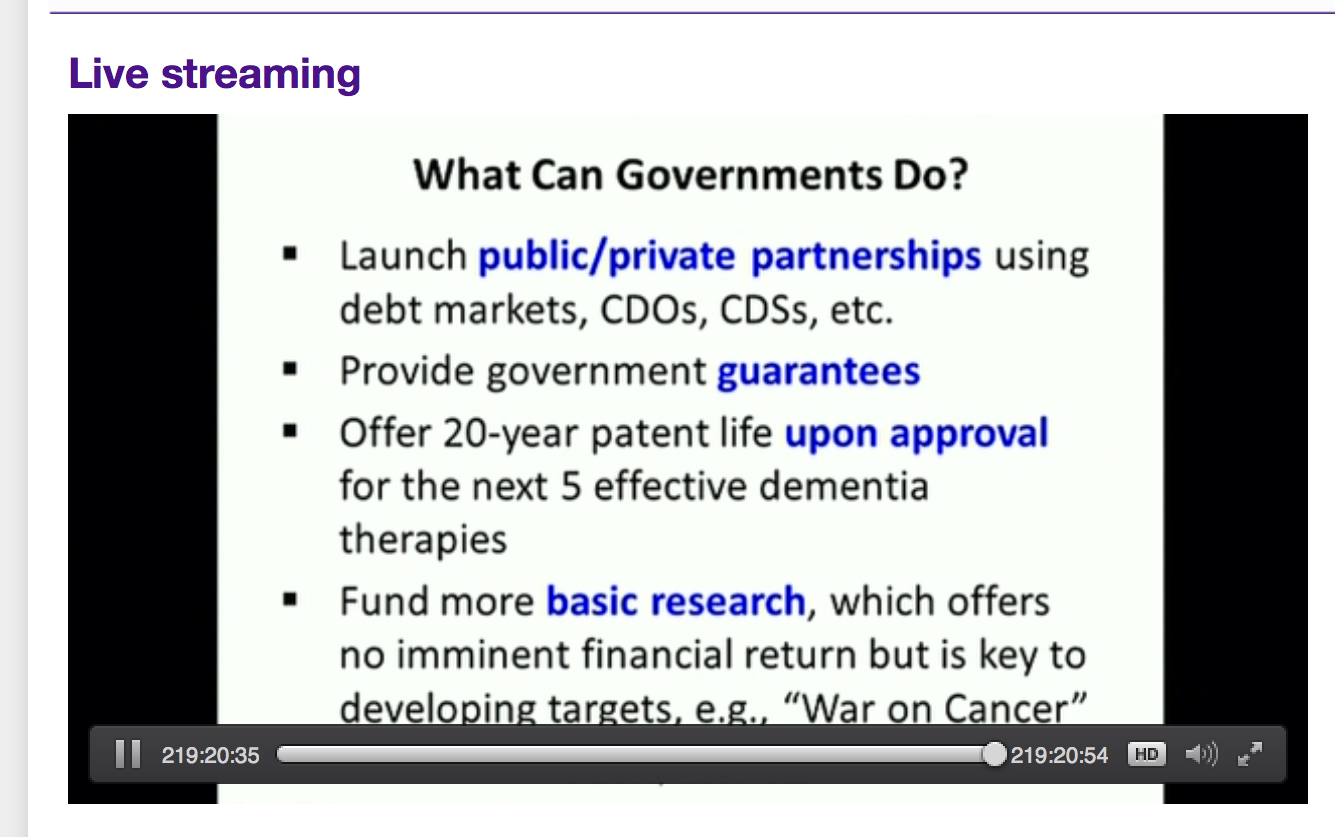

Innovation prizes

The “Longitudinal” Prize.

Case study: life story networks.

CHAPTER 17

Promoting leadership

Clear local strategies

The ‘Dementia Care Pathway’.

Supporting and motivating colleagues.

Leadership in person-centred care.

Disseminating science: antipsychotics.

The involvement of “people” in the JRF ‘four cornerstones’ model.

Corporate social responsibility, marketing and strategy.

The history of the Japanese befriending policy and implications for England.

Promoting dementia in schools.

Some real-life experiences.

CHAPTER 18

Conclusion

An overview of the current challenges for the English dementia strategy.

“Dementia friendly communities”: a sensible idea but bad label?

Future directions in research.

Future directions in care.

Have we arrived at a “dementia friendly society”?

A strategic plan for the future.