The following is the draft of an extract from my chapter “Stigma, citizenship and living better with dementia” in “Living better with dementia: how champions can break down the barriers”, by Shibley Rahman with Forewords by Prof Alistair Burns, Kate Swaffer and Chris Roberts.

The really important question therefore is: how can people living with dementia lead? A really important steer for this came from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in a report by Toby Williamson called “A stronger collective voice for people with dementia” (October 2012). The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) was a project which aimed to explore, support, promote and celebrate groups and projects led by or actively involving people with dementia across the UK that were influencing services and policies, affecting the lives of people with dementia. DEEP was a one year project which finished in Summer 2012. One of their key recommendations was that national and local organisations providing services or working with people with dementia need to develop and implement involvement plans, allocating resources to develop new groups, link groups together and help them share resources. Furthermore, it was recommended that researchers and research networks need to involve groups of people with dementia in helping to identify research topics, advise on research findings and undertake research on topics identified as important by people with dementia. Thankfully, this work has now been extended as part of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s work “Dementia Without Walls”, with various stakeholders also involved.

Ruth Bartlett erself found that keeping a diary has the potential to be used much more widely in patients living with dementia. In her opinion, the main advantage of this method is that unlike interviews, the diarist, rather than the researcher, is ultimately in control of how and when data are collected (e.g. Bartlett, 2011). Bartlett argues that diaries encourage participants to record thoughts and feelings as and when they occur and wherever they feel most comfortable; it therefore has the potential to compensate for short-term memory problems associated with dementia, plus it could help to minimise ‘respondent burden’ traditionally associated with interview based studies involving people with dementia (Cottrell and Schulz, 1993, p. 209). Bartlett has further suggested that people living well with dementia are willing, able to campaign, and presenting this at national and international conferences.

Dementia Alliance International (DAI) is the first global group, of, by and for people with dementia, where membership is comprised exclusively of people with dementia. Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International (DASNI) was the first organisation set up in 2001 by people with dementia; however their membership was not exclusive to people with dementia. There subsequently saw a sprinkling of groups at national levels, the Scottish Dementia Working Group (2002), the European Dementia Working Group (2012) and the Australian Dementia Working Committee (2013) were set up with membership of people with dementia, supported by their national Alzheimer’s organisations.

DAI was therefore established in January 2014 to promote education and awareness about dementia, in order to eradicate stigma and discrimination, and to improve the quality of the lives of people with dementia. DAI advocates for the voice and needs of people with dementia, and provides a global forum, aiming to unite all people with dementia around the world to stand up and speak out.

In the last few years, the voices of people with dementia around the world have become stronger, with leaders including Richard Taylor, Janet Pitts and Kate Swaffer. More recently a number of people with dementia have been discussing things globally, finally giving birth to DAI, to ensure issues such as social isolation, discrimination, stigma and exclusion are addressed. Their members wished to build a group consolidating the vast global networks of people with dementia now speaking and collaborating with each other over the Internet through blogs, Twitter, Pinterest, Facebook and other social media. The modern internet now offers incredible opportunities for organising social movements. too large or too difficult for a single person to undertake. In typical crowdsourcing applications, large numbers of people add to the global value of content, measurements, or solutions by individually making small contributions. Such a system can succeed if it attracts a large enough group of motivated participants,such as Wikipedia, Flickr and YouTube. These successful crowdsourcing systems have a broad enough appeal to attract a large community of contributors, giving true credibility to the idea that the whole is more than the sum of its constituent parts. And initial experience of people living well with dementia and the social media has led to interest in a related activity called ‘friendsourcing’. Friendsourcing attempts to synthesise social information in a social context: it is the “use of motivations and incentives over a user’s social network to collect information or produce a desired outcome, using as a guide what members of the network themselves consider to be important” (Bernstein et al., 2010).

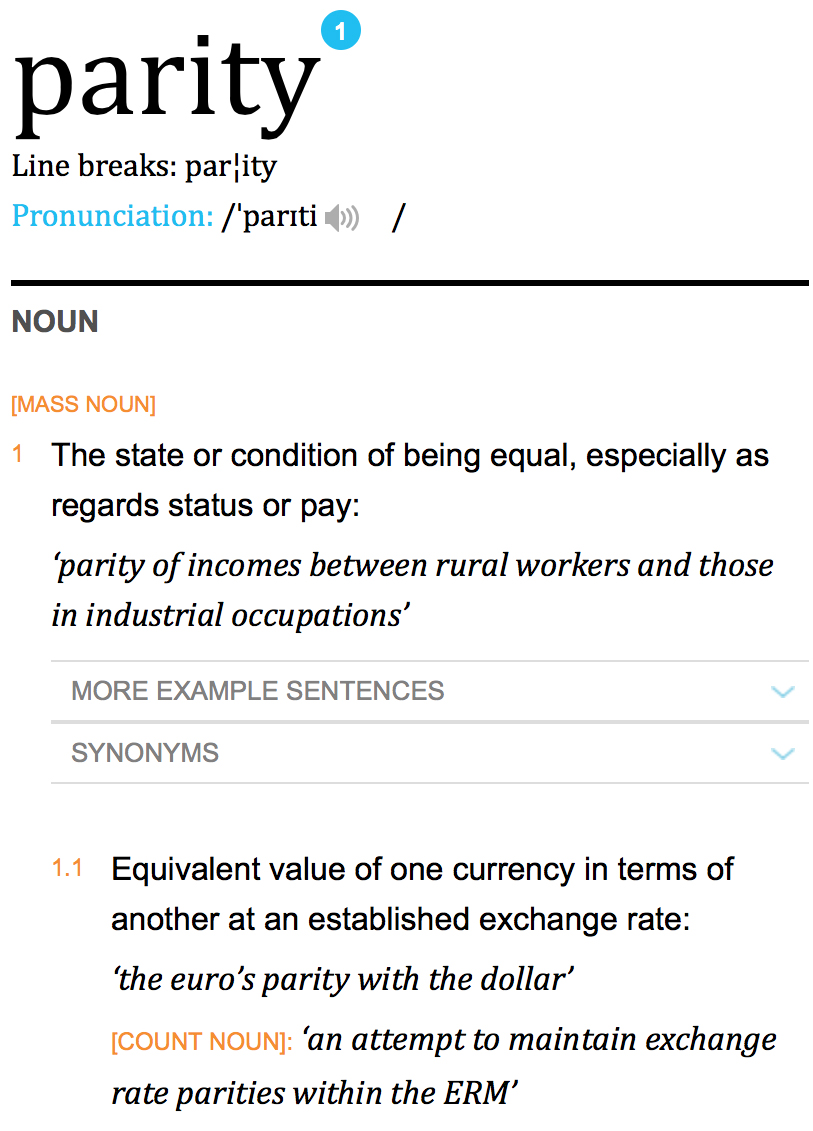

But the notion that dementia is a cognitive or behavioural disability puts the debate into an altogether different stratosphere. Instead of aspirational ‘dementia friendly communities’, a title which itself is open to abuse by politicians, other leaders and charities, the narrative then becomes treating persons with dementia for whom policies cannot serve to their detriment. That is unlawful, under indirect discrimination in various legal jurisdictions. That is therefore an enforceable right. But why is there a feeling that things have not improved much despite various global initiatives.

Batsch and Mittleman (2012) in their ADI World Alzheimer Report, “Overcoming the stigma of dementia” remark that:

“Government and non-government organisations in some countries have

been working tirelessly to pass laws aimed at eliminating discriminatory practices such as making people with dementia eligible for disability schemes. Regional organisations within countries have worked with local governments to improve access to services and delay entry to residential care, most of the time by trying to reduce stigma amongst family carers and health and social service professionals through increased education and regulations.”

Beard and colleagues (2009) offer practical suggestions for how a volte face in thinking could come about:

“Study participants reported various ‘rough spots’ along the path of dementia and their strategies for circumventing them. There were personal, interactional, and environmental factors that caused them difficulties. Strategies included concrete activities, emotional responses, and environmental adaptations. Respondents used cognitive aids, made various modifications, garnered assistance from others, and practiced ‘acceptance’ to deal with persistent problems. Barriers resulted from the disease itself as well as personal obstacles and pressures from others. Participants clearly demonstrated that their lives were meaningful and could be further enriched through advocacy, a positive attitude, and physical, mental, and social engagement. These data show persons with dementia performing the emotional work of illness management, incorporating related contingencies into everyday life, and reframing their own biographies. As they creatively adapted and constructed meaning, order, and selves that were valued, respondents demonstrated agency by actively accommodating dementia into their lives rather than allowing it to be imposed upon them by structural forces.”

The highly intriguing aspect now is that even the narrative of ‘involvement’ is being reframed. This was indeed warned about by Beresford (2002) who suggested service user involvement has emerged out of two different rationales for participation – one consumerist, the other democratic. The former claims that greater efficiency, efficacy and effectiveness will result from appropriately-placed service user feedback mechanisms. The latter, democratic approach, often framed in a rights discourse, views user participation as a form of self advocacy. The history of mental health activism can be dated far further back, to 1620, when inmates at the Bedlam asylum petitioned for their rights (Weinstein, 2010). That the DAI finds itself having attracted the attention of large charities, Big Pharma and social enterprises promoting living well with dementia is not altogether surprising therefore, even despite its relatively young existence.

References

Bartlett, R. (November 2011) Realities Toolkit #18: Using diaries in research with people with dementia.

Batsch, N. L., Mittelman, M. S. (2012) World Alzheimer’s report. Overcoming the stigma of dementia. Executive summary. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

Beresford, P. (2002) ‘User Involvement in Research and Evaluation: Liberation or Regulation? Social Policy & Society, vol. 1(2), pp. 95-105.

Cottrell, V., Shulz, R. (1993) The perspective of the patient with Alzheimer’s disease: A neglected dimension of dementia research, The Gerontologist, 33 (2), 205-211.

Weinstein, J. (2010) Mental Health, Service User Involvement and Recovery, London: Jessica Kingsley.