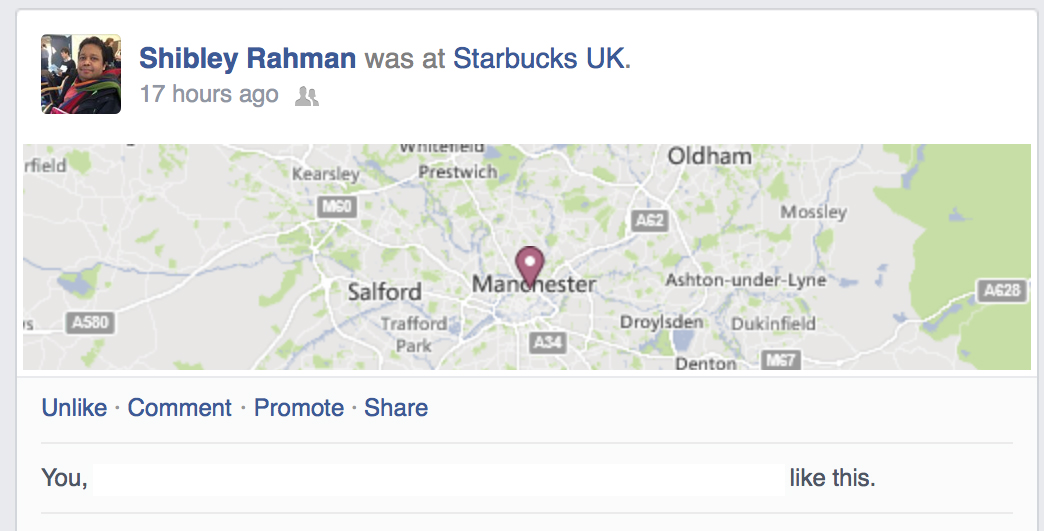

When I posted this on my Facebook yesterday

it was on the back of a joke that Chris Roberts and Kate Swaffer, both friends of mine, had GPS trackers on me.

I intend to tackle the potential beneficial use of GPS trackers for some people living with dementia at significant risk of travelling way beyond their local environment.

And travelling beyond my comfort zone is exactly what happened to me at the end of last week.

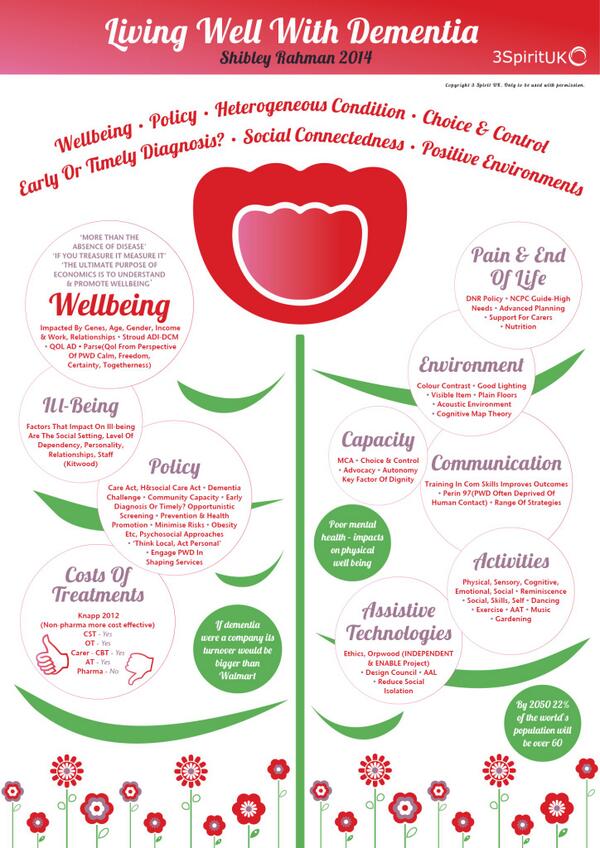

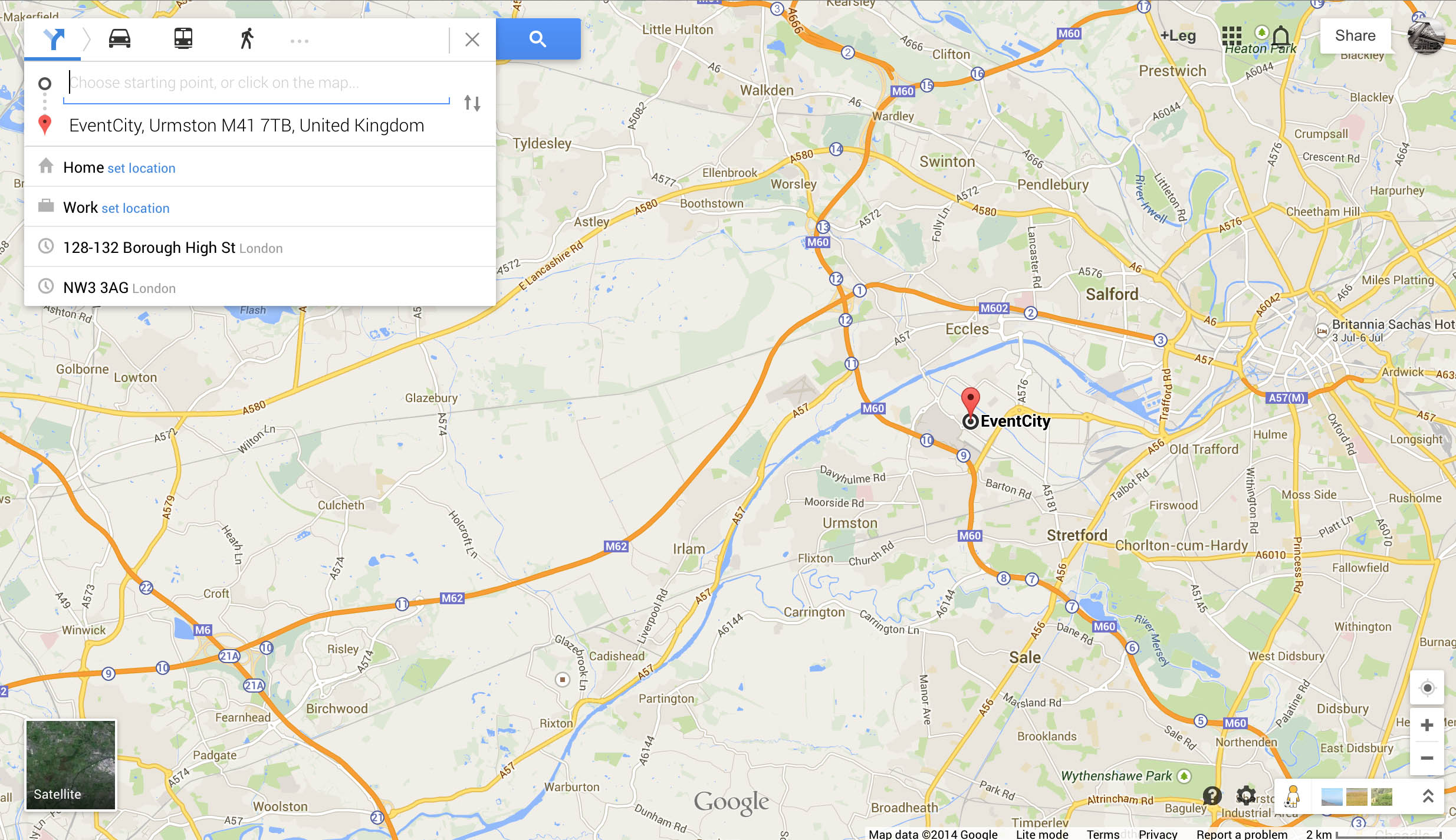

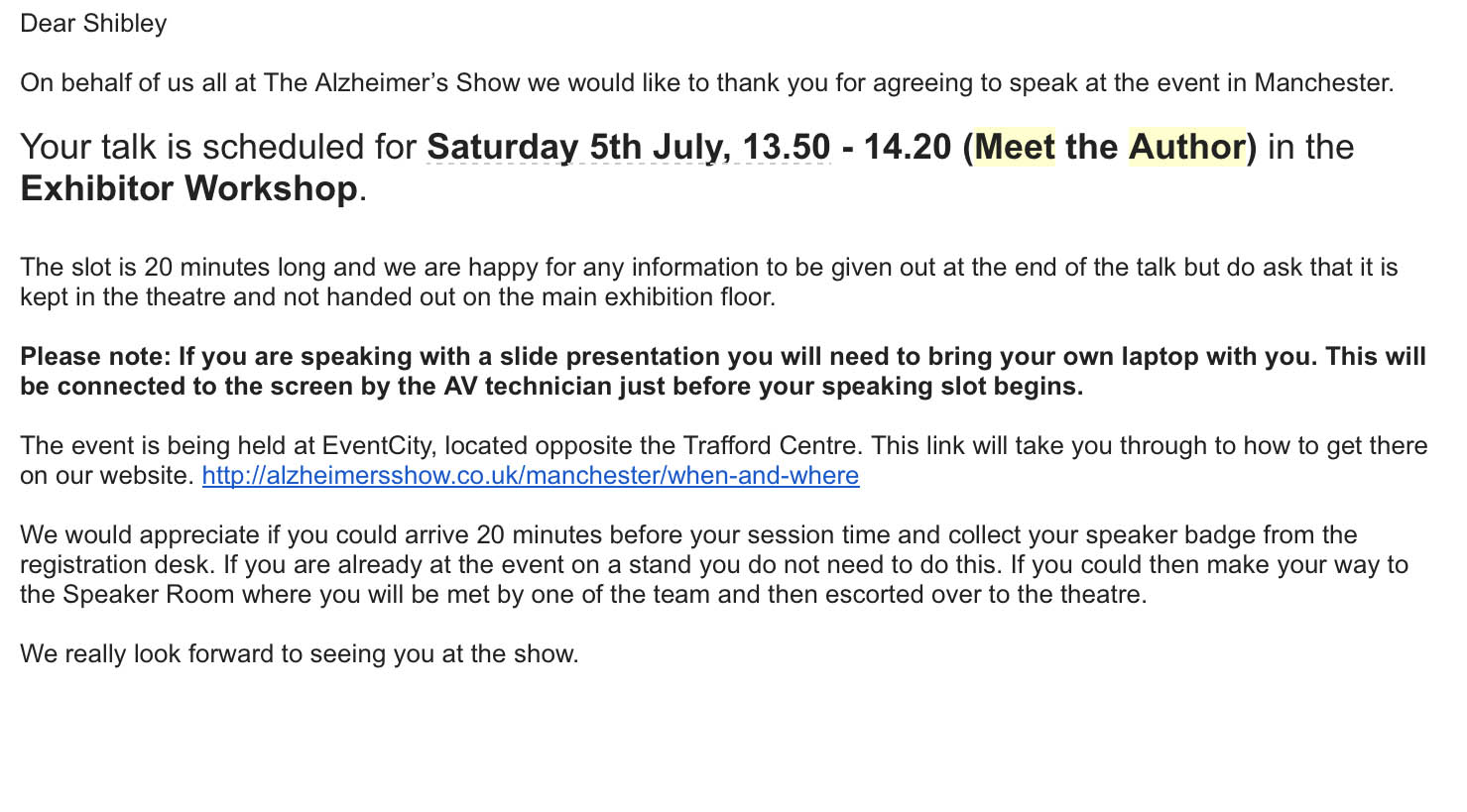

I ended up at the Alzheimer’s Show in Manchester, to give a 20 minute skit on my book ‘Living well with dementia‘.

Tommy Dunne and Chris Roberts, bosom buddies, sat together in a little section of the workshop. I could spot they were listening to every word.

Jayne Goodrick asked me a gentle question – unlike the question I asked from Prof Stuart Pickering Brown the day previously,

“I’d like to ask Prof Pickering Brown, but this question applies to the rest of the panel too, how the millions spent on Big Data and identifying genetic factors for Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia, like TREM2, can be rationalised in the context of a social care system on its knees, with zero hour contracts and breaches of the national minimum wage?”

I had of course pre-warned the panel that the question would be incomprehensible, as I am disabled.

Jayne said the question was ‘coded’, but Prof Pickering Brown likewise answered in code.

And he took the question well – I had a chance to thank him for all the work he does on frontotemporal dementia, and he asked me to pass on his personal regards to Prof John Hodges.

John is one of THE leading experts in frontotemporal dementia, well respected around the world in academia.

More importantly, he is looking forward to my new book, “Living better with dementia: how champions can challenge the boundaries”.

Chris especially feels, and Tommy agrees, that a much more suitable title would be ‘Living better with dementia.”

Now that Chris has explained it, I completely agree. “Living well with dementia” implies imposition of your judgment as to what living well is.

And whatever your objective level of living might be, nobody can deny a need to live better.

It took me some time to get it, but I did in the end.

A bit like how the penny dropped with Tommy’s joke about urinating with the door open.

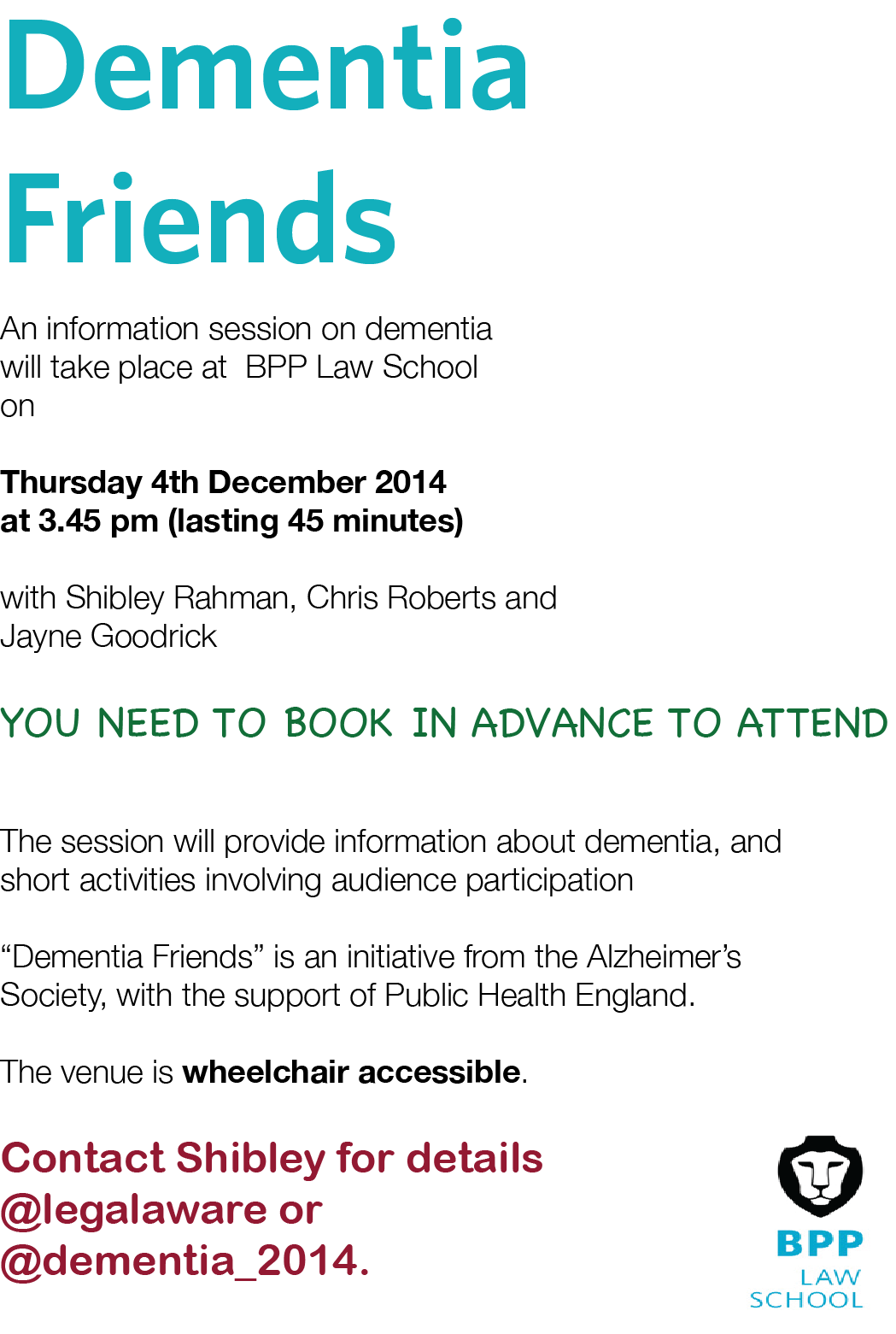

But I loved ‘The Alzheimer’s Show’ as it felt truly as if I was amongst friends – and I met people whom I have only met on Twitter, who were truly lovely : Suzy Webster, Natasha Wilson, Chris Roberts, Jayne Goodrick, Tommy Dunne.

And I met some wonderful friends from before: Louise Langham, Carers’ Coordinator for CC2A, and Rachel Niblock.

And I met some brilliant people who’d been following me on Twitter, such as Tracey from CareWatch.

I phoned Nigel Ward, the Show Director, and he was brilliant as usual: “Why did you phone me Shibley? There’s no signal in here, and I was only in the next-door cubicle?”

Anyway, I’ve been on and off in the dementia field for seventeen years, which has taken me on various ups and downs, including three months on the dementia and cognitive disorders firm under Prof Martin Rossor as a junior doctor at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square.

It’s also seen me go via a 2 year 10 months PhD at the University of Cambridge. I was the first person in the world to demonstrate reliably risky decision-making behaviour in persons with the behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. It’s a finding which has been resilient for the last fifteen years, having been replicated and explained through neuroimaging.

I am not really into ‘co-production’, mainly having seen it being used as a cover for legitimising some people’s pre-formed agendas.

But I have been heavily influenced by Kate Swaffer who received a diagnosis of dementia some years ago.

The contents of my new book, to be submitted by the end of October 2014, reflect mutual interests of ours. Kate is more than a cook, former nurse, brilliant blogger, and advocate for Alzheimer’s Australia.

I am honoured she is a close friend of mine. She is not motivated by any narcissistic twang.

She is brilliant.

She has taught me more about dementia than anyone I know.

And it’s her birthday today.

#KoalaHugs