There’s an old-fashioned idea that the only relationship which matters is the one between the person living with dementia and the medical Doctor. I oompletely sympathise with the concern surrounding the idea ‘we are all patients now’, where, for example, people experiencing memory problems as a natural part of ageing get overmedicalised as ‘dementia’, perhaps for the purpose of hitting a national target: that well people are in fact the undiagnosed ones. But, likewise, my own experience as a person living with physical disability is that we are all persons who become patients at the point of becoming ill. I therefore think the term ‘patient leader’ is outdated, unless there is a specific group of people who only consider themselves ill.

I am not a ‘believer’ that I belong in an interconnected world by virtue of the fact that I have a Facebook account, but I do feel part of a wider network of knowledge, behaviours and skills. I feel that I can draw on this talent if I need support in me living independently, or care if I have unaddressed needs. When I could barely speak and move, soon after my meningitis, I was helped by a carer who is in fact to this day is one of my best friends. For too long, carers, I feel, have been airbrushed out of the picture. The clue is in the name ‘Whole Person Care’. Carers matter, and they should be given the prestige and status they so strongly deserve.

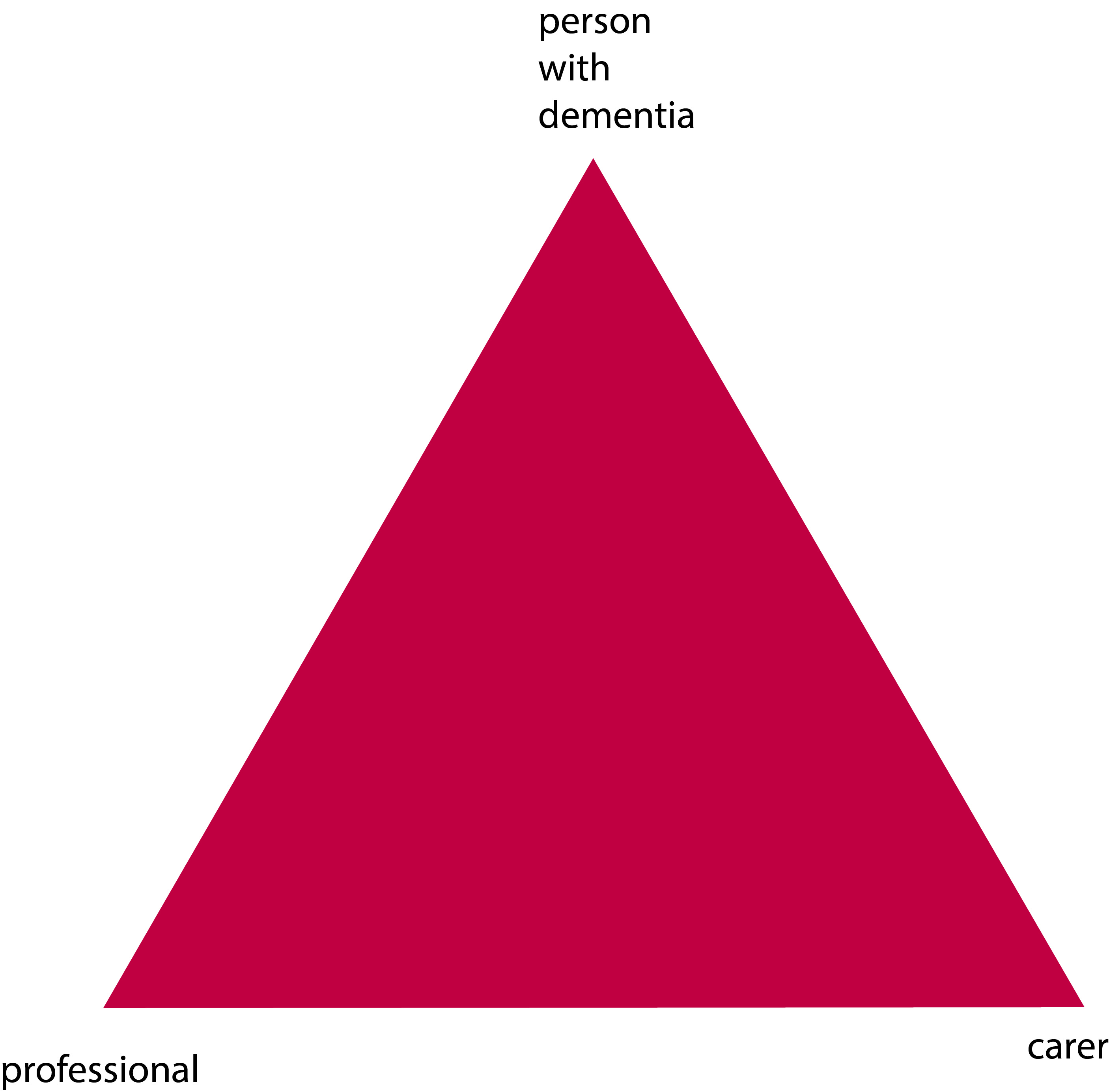

The landscape is though gradually changing, for the better. The “Triangle of Care” describes a therapeutic relationship between the person with dementia (patient), staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports communication and sustains wellbeing (Carers Trust, 2013). Carers often report that their wish to be effective often compromised by failures in communication, possibly because some people are unwilling listen.

At critical points, carers can be excluded by staff, and requests for helpful information, support and advice are not acted upon. Sadly we need to address the fact that medical professionals need specific training in working with carers, not working against them. This needs to include training in communication strategies with people with dementia, thus enabling people with dementia to be engaged for as long as possible.

redrawn from Carers’ Trust [Triangle of Care]

We currently have a dearth of research of this triangular relationship – but plenty on the ‘dyadic’ relationship between professional and carer. Most studies on patient–physician relationships and communication have focused on the dyadic interaction between the parties and the type of exchanges occurring among them. However, up to 60 percent of medical encounters involving elderly persons are threesomes (Adelman, Greene and Charon, 1987). The features of such relationships differ fundamentally from those of a dyad. The very presence of a third person may affect the basic patient–physician relationship (Kealy and Nolan, 2003) negatively by limiting patients’ involvement and assertiveness or actual exclusion from the care discussions (Greene et al., 1994), or positively by enhancing physician–patient communication and consequently superior comprehension and involvement by accompanied rather than unaccompanied patients (for example Clayman et al., 2005).

A person coming into contact with the health and care services currently do so from the point of a possible diagnosis. Results from the study from Zaketa and Carpenter (2010) were also actively seeking evaluation of their cognition and were subsequently diagnosed relatively early in their disease progression appear to suggest that physicians do not utilise patient-centered behavious such as emotional rapport building at first. Only once patients and carers are experiencing and demonstrating overt distress associated with more severe symptoms, or as physicians are delivering more dire news regarding the patient’s prognosis and ability to live independently, does a three-way relationship begin to kick in. Hubbard and colleagues (Hubbard et al., 2009) had concluded that carers are involved in treatment decision-making in cancer care and contribute to the involvement of patients through their actions during, before and after consultations with clinicians. Carers can act as funnels for information from patient to clinician and from clinician to patient. They can also act as facilitators during deliberations, helping patients to consider whether to have treatment or not and which treatment.

And English dementia policy can learn usefully not only from cancer. In paediatrics, De Civita and Dobkin (2009) revisited the term “triadic partnership”, in referring to “the therapeutic triangle in medicine that includes the carer, child, and medical team in facilitating adherence to treatment”. Optimal health, one may argue, is achieved when patients, carers, and health care providers collaborate in designing a manageable treatment program (Rapoff, 1999). This in time may impact on the policy for self-care. According to Strachan and colleagues, a better understanding of the individual factors that influence heart failure self-care is necessary for interventions to be more responsive to the needs and preferences of patients (Strachan et al., 2013). Individual factors known to affect heart failure self-care are thought to include the individual’s ability to manage comorbid conditions, depression or anxiety, sleep disturbances, age/developmental issues, levels of cognitive function, and health literacy (Riegel et al., 2009). But people are increasingly cognisant of the milieu of the effects of other agents.

The purpose of the analysis by Dalton (2002) is to describe the construction and initial testing of the theory of collaborative decision-making in nursing practice for a triad. The inclusion of a third person (family carer) in the theory required the addition of concepts about the carer, coalition formation, and nurse and carer outcomes. And other groups of patients can also helpfully inform on this debate. Patients themselves are increasingly been seen as critical ‘partners in care’. Hirsch and colleagues have outlined reasons why partners-in-care approaches are important idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, including the need to increase social capital, which deals with issues of trust and the value of social networks in linking members of a community (Hirsch et al., 2013).

I feel the answer comes not through dyads or triads, but by considering whole networks of care for the whole person. As observed elsewhere, although each professional group (e.g. nursing, neurology, physiotherapy) makes its own assessment of the needs of the patient, it appears that it is the integration of the assessment and service delivery that is perceived to be the most useful method to address the health-care needs of these patients (McCabe, Roberts and Firth, 2008). And there’s no doubt for me that this involves effective verbal and non-verbal communication all round.

Primary care visits of patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) often involve communication among patients, family carers, and primary care physicians (PCPs). The objective of the study by Schmidt and colleagues was to understand the nature of each individual’s verbal participation in these triadic interactions (Schmidt, Lingler and Schulz, 2009). Carers of DAT patients and PCPs maintain active, coordinated verbal participation in primary care visits while patients participate less. Interestingly, the carers’ verbal participation in triadic interaction was found to be also related to their reports of satisfaction with the primary care visit, specifically their satisfaction with interpersonal treatment of the patient with DAT by the PCPs. The literature is becoming, however, increasingly vigilant of the cautions in observing patient satisfaction as the outcome for a clinical consultation. In a study from Sakai and Carpenter (2011), videotapes of dementia diagnosis disclosure sessions were reviewed to examine linguistic features of 86 physician–patient–companion triads. Verbal dominance and pronoun use were measured as indications of power. Physicians dominated the conversation, speaking 83% of the total time. Evaluating patient expectations and preferences regarding physician communication style may be the most effective way of promoting patient-centered healthcare communication. To explore and gain further insight into the nature of the triadic interaction among patients, companions and physicians in first-time diagnostic disclosure encounters of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-clinic visits were studied by Karnieli and colleagues (Karnieli-Miller et al., 2012). Twenty-five real-time observations of actual triadic encounters by six different physicians were analysed, The authors found that an effective and empathic management of a triadic communication that avoids unnecessary interruptions and frustrations requires specific communication skills (e.g., explaining the rules and order of the conversation).

This is why feel two’s company, and three’s a very good thing, for English dementia policy. But I feel that wider networks at large are going to be proved to be important for whole person care, though some agents may possibly be more significant than others.

References

Adelman, R.D., Greene, M.G., Charon, R. (1987) The physician–elderly patient–companion triad in the medical encounter: the development of a conceptual framework and research agenda, The Gerontologist, 27, pp. 729–34.

Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care, Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England, Second Edition (812 KB) http://static.carers.org/files/the-triangle-of-care-carers-included-final-6748.pdf

Clayman, M.L., Roter, D., Wissow, L.S., Bandeen-Roche, K. (2005) Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits, Soc Sci Med, 60, pp. 1583–91.

Dalton, J.M. (2003) Development and testing of the theory of collaborative decision making in nursing practice for triads, J Adv Nurs, Jan, 41(1), pp. 22-33.

De Civita M, Dobkin PL. Pediatric adherence as a multidimensional and dynamic construct, involving a triadic partnership. Pediatr Psychol. 2004 Apr May;29(3):157-69.

Greene, M.G., Majerovitz, S.D., Adelman, R.D., Rizzo, C. (1994) The effects of the presence of a third person on the physician–older patient medical interview, J Am Geriatr Soc, 42, pp. 413–9.

Hirsch, M.A., Sanjak, M., Englert, D., Iyer, S., Quinlan, M.M. (2014) Parkinson patients as partners in care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014 Jan;20 Suppl 1:S174-9.

Hubbard, G., Illingworth, N., Rowa-Dewar, N., Forbat, L., Kearney, N. (2010) Treatment decision-making in cancer care: the role of the carer. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Jul;19(13 14):2023-31.

Karnieli-Miller, O., Werner, P., Neufeld-Kroszynski, G., Eidelman, S. (2012) Are you talking to me?! An exploration of the triadic physician-patient-companion communication within memory clinics encounters, Patient Educ Couns, Sep, 88(3), pp. 381-90.

Keady, J., Nolan, M. (2003)The dynamics of dementia: working together, working separately, or working alone? In: Nolan MR, Lundh U, Grant G, Keady J, editors. Partnerships in family care: understanding the care-giving career. Buckingham: Open University Press, p. 15–32, 2003.

McCabe, M.P., Roberts, C., Firth, L. (2008) Satisfaction with services among people with progressive neurological illnesses and their carers in Australia, Nurs Health Sci, Sept, 10(3), 209-215.

Rapoff, M. A., Lindsley, C. B., Christophersen, E. R. (1985). Parent perceptions of problems experienced by their children in complying with treatments for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 66, pp. 427–429.

Riegel, B., Moser, D.K., Anker, S.D., Appel, L.J., Dunbar, S.B., Grady, K.L., Gurvitz, M.Z., Havranek, E.P., Lee, C.S., Lindenfeld, J., Peterson, P.N., Pressler, S.J., Schocken, D.D., Whellan, D.J., American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. (2009) State of science: promoting self care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, Circulation, 120, pp. 1141e63.

Sakai, E.Y., Carpenter, B.D. (2011) Linguistic features of power dynamics in triadic dementia diagnostic conversations. Patient Educ Couns, Nov, 85(2), pp. 295-8.

Schmidt, K.L., Lingler, J.H., Schulz, R. (2009) Verbal communication among Alzheimer’s disease patients, their caregivers, and primary care physicians during primary care office visits, Patient Educ Couns, Nov, 77(2), pp. 197-201.

Strachan, P.H., Currie, K., Harkness, K., Spaling, M., Clark, A.M. (2014) Context matters in heart failure self-care: a qualitative systematic review, J Card Fail, Jun, 20(6), pp. 448 55.

Zaleta, A.K., Carpenter, B.D. (2010) Patient-centered communication during the disclosure of a dementia diagnosis, Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen, 25(6), pp. 513 20.