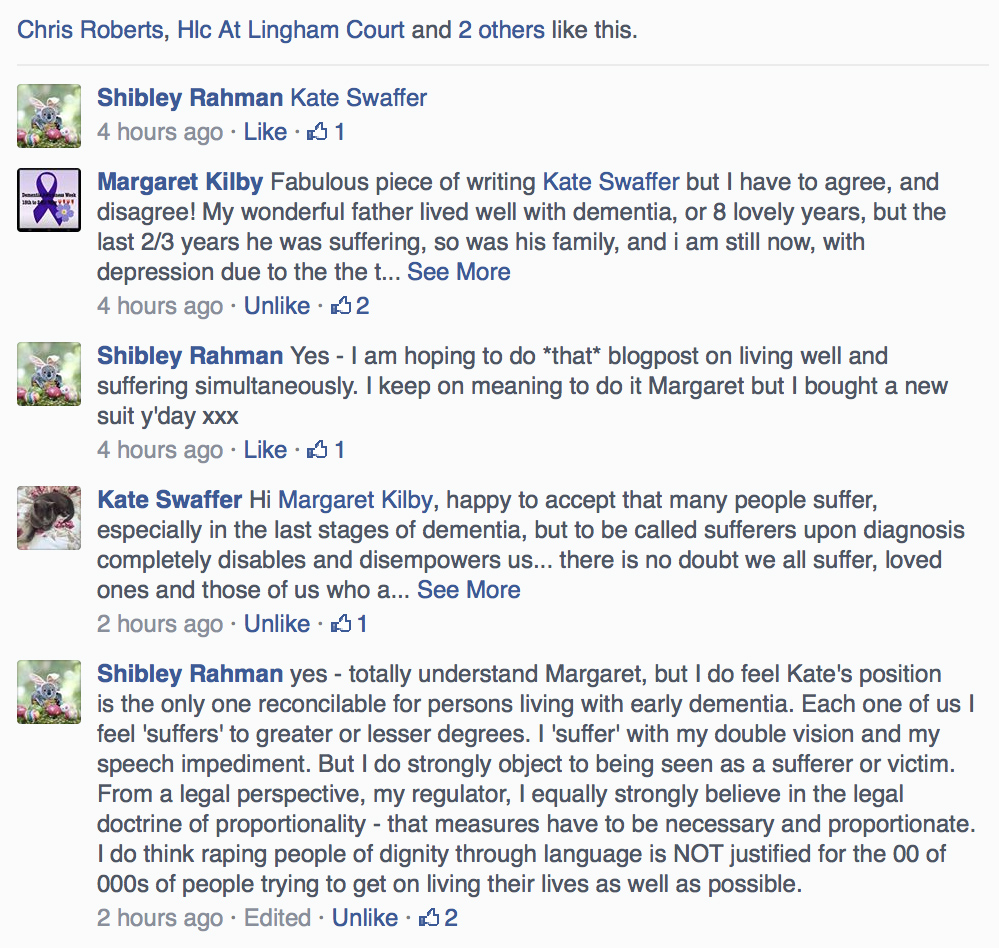

First, read Kate Swaffer’s poem. “Who’s suffering?”

When the media fires bullets of suffering in their magazines (quite literally), it is not clear who is the suffering by, what they’re suffering, how they’re suffering, when they’re suffering, and why they’re suffering.

Many readers suffer at this lack of clarity.

It’s pretty clear this narrative has got extremely distorted for no clear reason. What do the caring professions or the media have to gain by describing so much suffering?

And are people really suffering as purported?

Are there any randomised placebo-controlled drug trials where the relief of “suffering” in #dementia is a reported outcome?

Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer)’s poem conversely is a very helpful contribution, based on a personal experience of living well with a dementia.

“Rhetoric referring to Alzheimer’s disease as ‘the never ending funeral’ or ‘a slow unraveling of the self’ implies that diagnosed individuals and their families alike are victims of a dreaded disease.”

So comment Beard and colleagues.

“The fact that the words Alzheimer’s disease conjure up images of a hideous, debilitating condition demonstrates that an Alzheimer’s diagnosis can be both “a stigmatizing label and a sentence”. When depicted as a ‘living death’, Alzheimer’s can have countless social-psychological consequences for those diagnosed. Within a medical model, the relatives of persons with dementia are ascribed the role of ‘caregiver’ with a focus on the associated stressors or ‘burden’. Subsequently, health promotion efforts have historiiccally positioned family members as the ‘second’ or ‘hidden’ victims.”

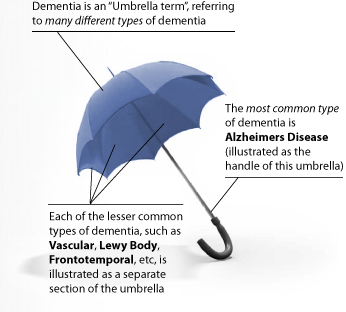

Of course, this discussion is not confined to Alzheimer’s disease.

It is not uncommon for people who love people living with advanced dementia to have a miserable time, and suffer from that.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of ‘dementia’, a disease of the brain. It’s not just about memory, although memory problems can be a common feature of Alzheimer’s disease early on in particular.

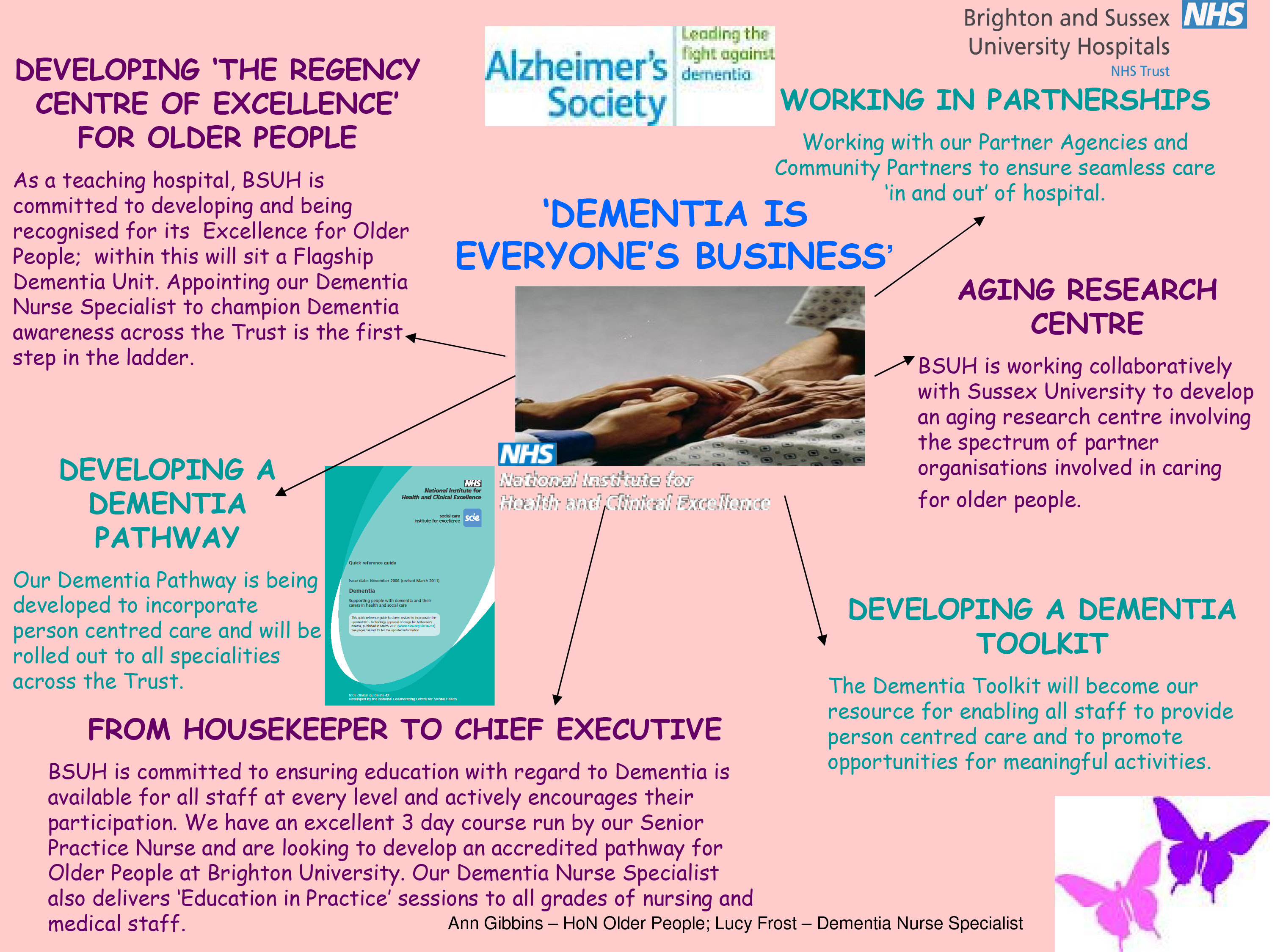

There is more to the person than the dementia. It’s possible to live well with a dementia. And dementia is not necessarily associated with ageing.

But some critics of ‘living well with dementia’ have attacked the concept saying it is trying to airbrush or sanitise suffering. I hope that this is not a widespread belief, as it is not true.

Across a number of jurisdictions, the word ‘sufferer’, like ‘victim’, is avoided in common parlance and academic papers when referring to people getting on with their own lives.

The term ‘live well with dementia’ is not indeed to enforce a degree of pleasantry on the lives of people. Contentment is not compulsory. But the term conveys a notion which is a pure and simple reaction to people being written off on the receipt of a diagnosis of dementia.

We owe much of the current drive in policy to ‘person centred care’ from the seminal work of the late great Prof Tom Kitwood on personhood. Persons living with dementia have been classified as “empty shells”, a label that may contribute to the development of paternalistic attitudes and behaviors toward care.

Kitwood suggested that people with dementia are often depersonalized and actively disempowered.

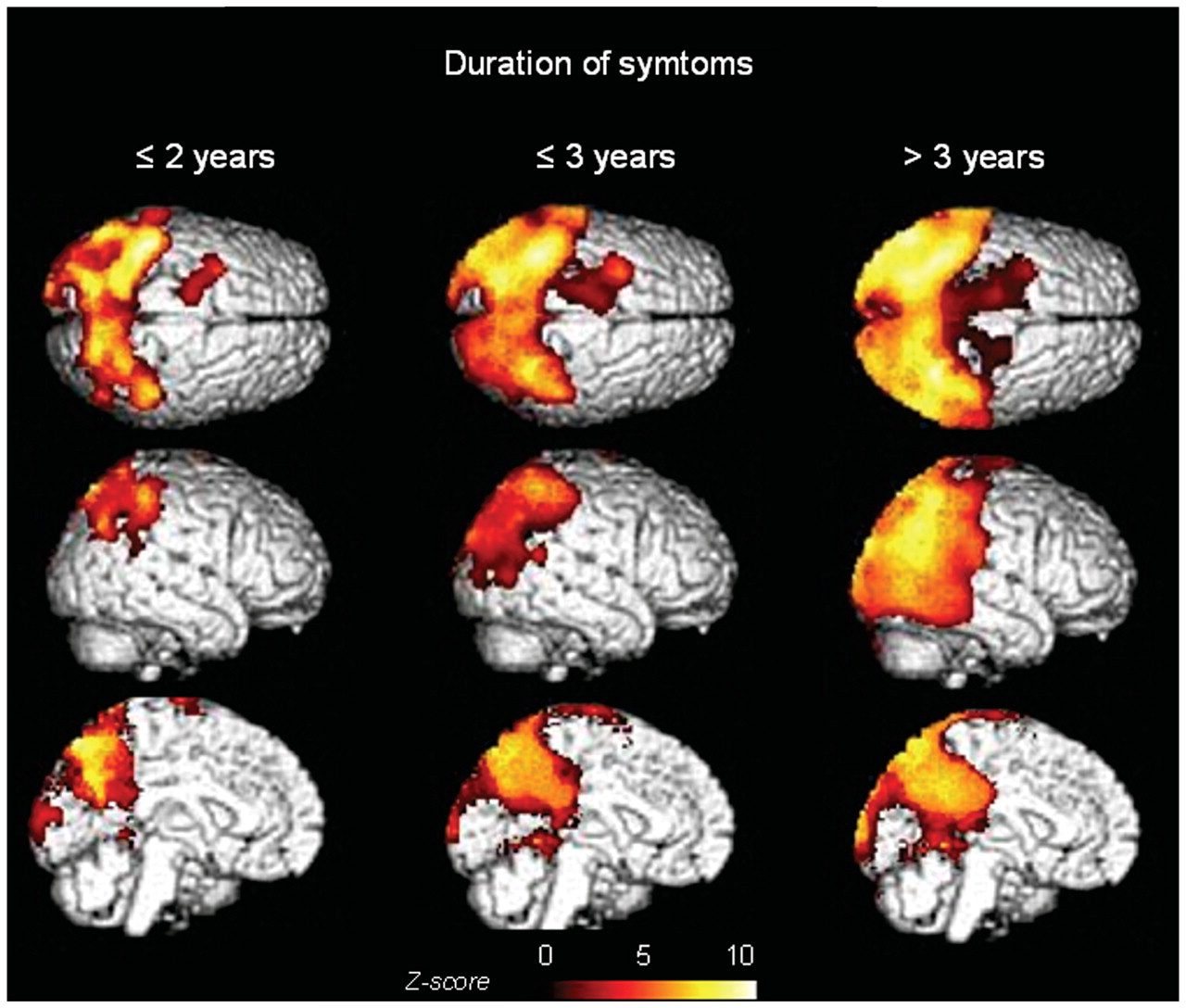

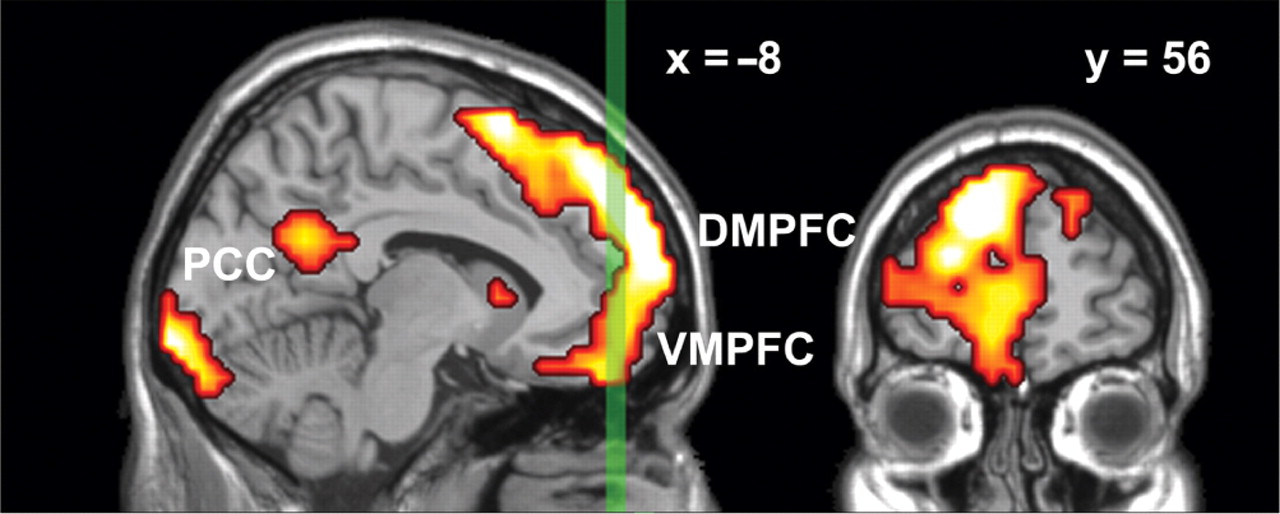

Research into the “self” in dementia is important for a number of reasons. It is important to understand how people with dementia experience their sense of self because this has implications for how people cope with the illness, how they relate to others, including friends, family, and health professionals, and what any types of intervention might be appropriate for them.

One person, interviewed by Wendy Hulko, described the experience as “hellish”.

But it turned out that this word was chosen partly out of word finding difficulties.

“Well, having um a difficulty coming out with the right words for example or phrases or um having difficulty with uh numbers and um dates, times, um having difficulty coming up with um, difficulty um, coming up with just a common expression uh, or um even words that are very frequently used by anyone without the disease and um having difficulty coming up with just ordinary expressions…”

Several of the participants dismissed the significance of having dementia, some focusing on the lack of impact it had on their lives. Several of the participants tolerated dementia, noting the inconvenience it caused and downplaying the negativity associated with it.

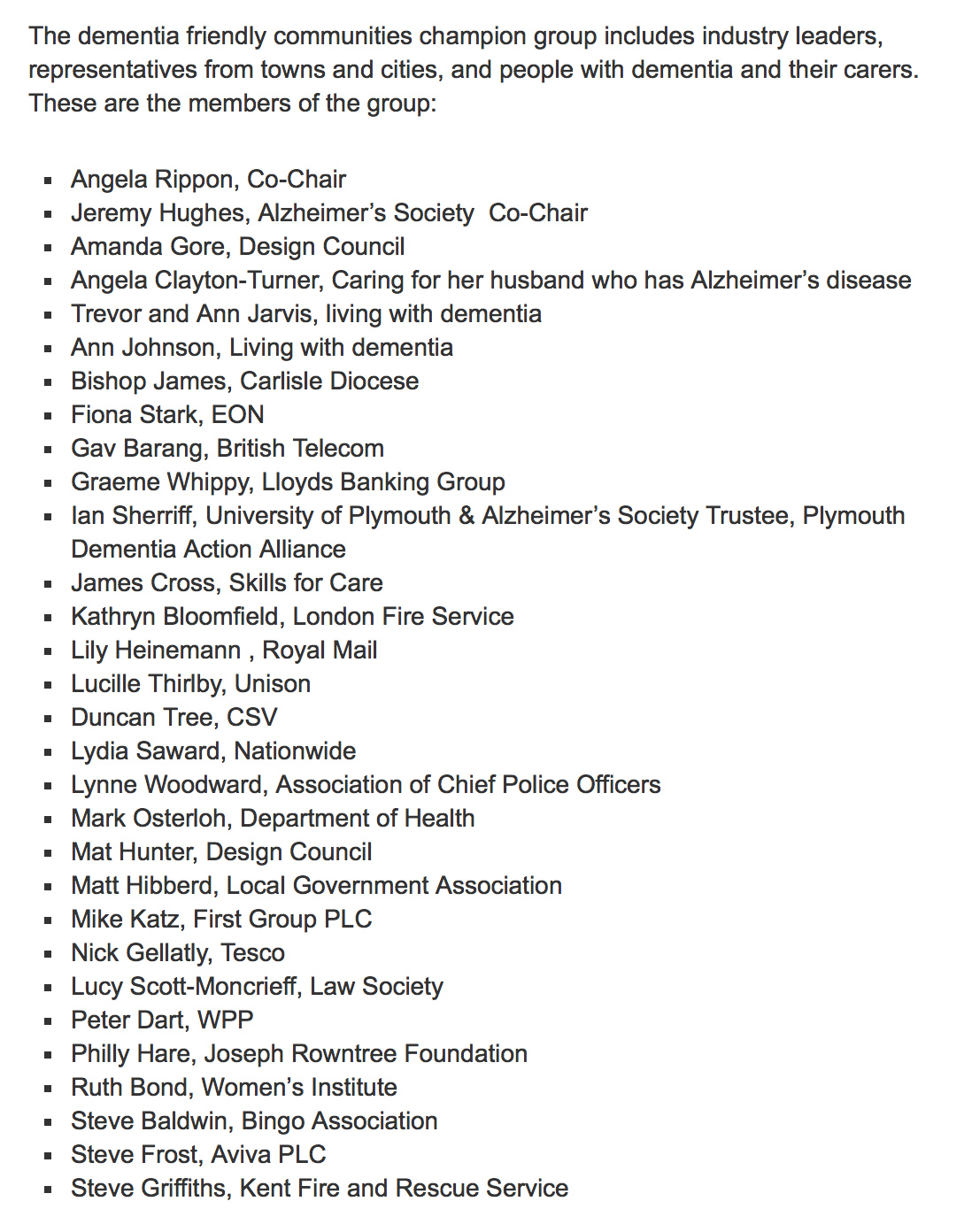

Despite extremely powerful national advocacy organisations founded over a quarter century ago in the United States and the United Kingdom, the voice of people with all forms of dementia has been surprisingly slow to emerge.

A recent exception to this has been the Dementia Alliance International.

The medical model has unintentionally forced a narrative in the media which does present people living with dementia in the positive light. Such ‘ringfencing’ of the person with dementia positions them as withdrawing from social life rather than considering how their social roles may have been withdrawn from them, which demotes them to ‘patient’ or ‘dementia sufferer’.

Such biomedical reductionism, arguably, can, therefore, create additional obstacles for diagnosed individuals and their families.

People with dementia, like all of us, undoubtedly have “rough spots” along an individualistic path of dementia, but the person is more important than the diagnosis as reflected in strategies for circumventing the rough spots.

There are typically personal, interactional, and environmental factors that caused them difficulties. Strategies included concrete activities, emotional responses, and environmental adaptations.

A number of devices can be used cognitive aids, made various modifications, garnered assistance from others’ engagement, akin to how people like me live with physical disability.

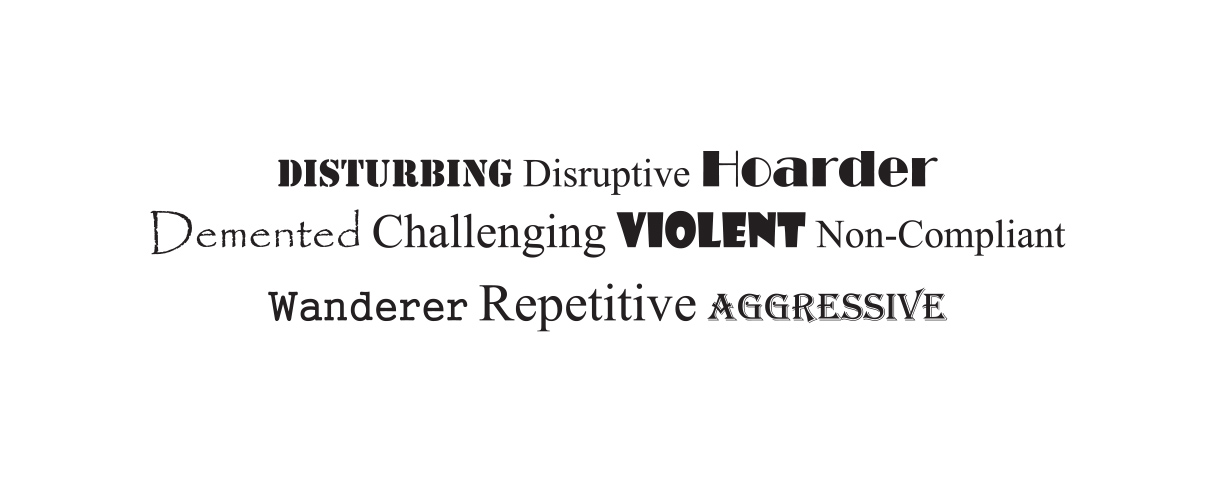

And often the language itself is intensely stigmatising.

Take for example this example by Dupuis and colleagues.

Such current language and discussion around “challenging behaviours” have the effect of blaming persons with dementia for behaviors and labeled persons as violent, aggressive, disruptive, challenging and so forth. This was hurtful and stigmatising and did not reflect the meanings of the actions of persons with dementia.

Conversely, it is quite often – and incredibly politically incorrect to say so – a failure by the care or support network to understand communication by a person with dementia amidst intense frustration.

Sarah Lamb notes at the beginning of this year that the current North American “successful ageing” movement offers a particular normative model of how to age well, one tied to specific notions of individualist personhood emphasising independence, productivity, self-maintenance, and the individual self as project.

However, Lamb concludes that the “successful ageing” narrative “might do well to come to better terms with conditions of human transience and decline, so that not all situations of dependence, debility and even mortality in late life will be viewed and experienced as “failures” in living well.”

This thought is bound to raise eyebrows.

An emerging political approach suggest that individuals with dementia are viewed as having transgressed “core cultural values—productivity, autonomy, self-control, cleanliness—and these failures damage the ‘victim’s’ status as an adult, and indeed, full humanity” (Herskovits, 1995: 153).

In articulating a “political” model of dementia, Susan M. Behuniak suggests that one is inviting very different meanings:

“everything from absolute control over the individual to a total lack of public policy, from an emphasis on individual rights to that of social responsibility, and from laws that draw absolute lines to those that accommodate shades of grey.”

Although dementia is not traditionally viewed as a power question but as a medical condition, power in its most traditional of formulations can be seen when debates arise over who should decide matters involving the individual with dementia.

This is, I feel, also an issue when we talk about a ‘carer’ or ‘support’ for a person with dementia. Whilst not as unsubtle as the word ‘sufferer’, there is an implicit power relationship there for me.

Chris Roberts [@mason4233], one of the @DementiaFriends, himself a card-carrying member of the ‘living well with dementia’ club has often remarked as follows:

So it is possible to suffer and live well with dementia.

But once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met only one person with dementia.

But hold on.

Carly Findlay, like Chris and Kate, also puts it beautifully, this time writing from Melbourne about “ichthyosis“.

In her piece, “I get told I suffer… I don’t suffer.”

Ask others for their opinion if possible, or those closest to them.

It’s very important that no views are simply shouted down, particularly since it will be an important strand of the English dementia strategy (probably from next year.)

Further reading

Herskovits, E. (1995). Struggling over subjectivity: Debates about the ‘self