Personhood and the environment interact in a complex way for a person living well with dementia.

However, it is generally not feasible to address these issues in a busy GP practice, whatever the best will in the world; nor even in hospital or specialist tertiary unit care.

The G8 Dementia Summit and the World Dementia Council (which has no persons with dementia or carer representatives) were and are outstanding at promoting the interests of the big pharmaceutical industry companies and elected politicians.

The evidence for the beneficial effects of drugs used commonly to treat specifically dementia on quality of life measures can at best be described as scanty.

The opportunity cost of 493 pages of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and an ensuing £3bn top down reorganisation, and £2.5 mn spent on ‘Dementia Friends’ from Public Health England (delivered by the Alzheimer’s Society), is that many issues were simply kicked into the long grass.

When I turned up at the “Alzheimer’s Show” this weekend, opinions from families which had somehow encountered persons receiving a clinical diagnosis of dementia were at fever pitch.

It was not uncommon for me to hear of ‘non existent’ post diagnostic support. Many individuals were simply desperate for somebody to take on the rôle of ‘care coordinator’, exasperated at spending hours on trying to navigate through the benefits and legal systems inter alia, even parking aside health and social care.

We simply cannot go on like this.

I found a situation where many social enterprises reported having been rogered backwards through the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge. While people invariably recounted how wonderful it would be for society to be more welcoming and understanding of people living with dementia, they found current initiatives rather superficial and patronising.

What they really wanted was real practical help on the ground.

Caregivers of all types, including paid carers on zero hour contracts and unpaid family members, reported to me being totally exasperated about soldiering on regardless. Many reported to me how they did not feel that they had taken on a caring rôle even. Some reported their unease about whether their care and support were any good.

Social prescribing could however be the ‘next big thing’.

It is a means of enabling primary care services to refer patients with social, emotional or practical needs to a range of local, non-clinical services, often provided by the voluntary and community sector.

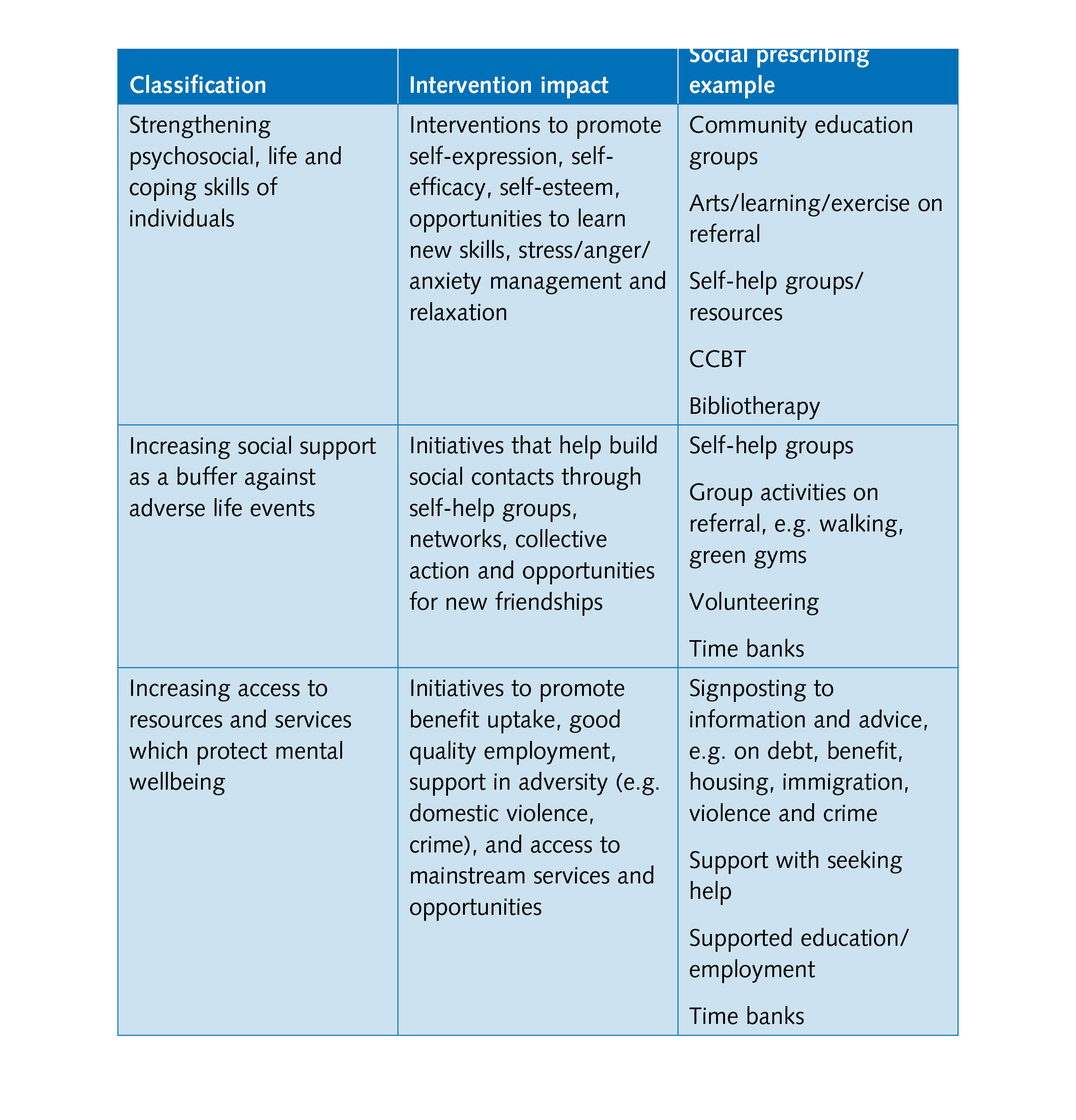

Research into social prescribing reports tend to report benefits in three key areas: improving mental health outcomes, improving community wellbeing, and reducing social exclusion which is relevant for older people with depression or who are socially isolated, both increasing problems in society.

As one example, “information prescriptions” might be particularly beneficial to individuals living with a long-term condition or social care need such as dementia, in consultation with a health or social care professional.

Information prescriptions, it is hoped, will guide people to relevant and reliable sources of information to allow them to feel more in choice and control and better able to manage their condition and maintain their independence.

Broadly, social prescribing is one route to providing psychosocial and/or practical support for:

- vulnerable and at risk groups, for example low-income single mothers, recently bereaved elderly people, people with chronic physical illness, and newly arrived communities;

- people with mild to moderate depression and anxiety;

- people with long-term and enduring mental health problems; and

- frequent attenders in primary care.

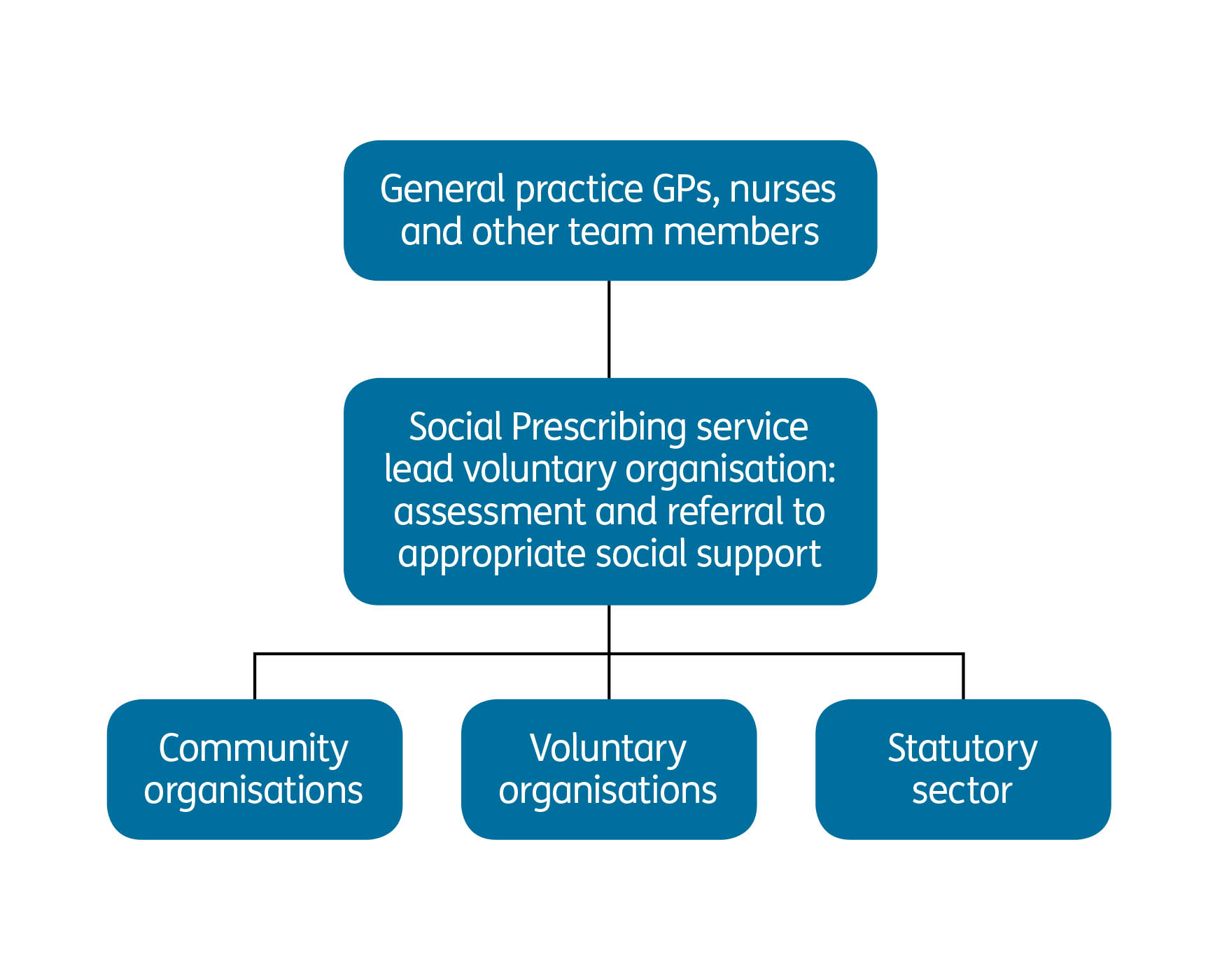

There have been various permutations of it trialed around the county, but the basic design is like this.

One particular “Social Prescribing Pilot Project” has already demonstrated a successful model of partnership working between the voluntary sector and general practitioners and can be replicated.

This pilot project worked with 12 GP practices and six local Age UKs across Yorkshire and Humber.

General practitioners referred 55 older people who had mild to moderate depression or were lonely and socially isolated to the Social Prescribing service at their local Age UK.

As part of the authorisation process, clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) are required to demonstrate that they have mechanisms in place to work with voluntary-sector groups.

63 referrals to Age UK services including befriending services, day clubs, information and Advice, benefit checks, trips, Theatre outings, advocacy, legal advice, and art groups.

Funded Voluntary and Community Sector providers have benefited from the opportunity to broaden and diversify their provision for people with complex needs. It has enabled a number of smaller community level providers to engage with health commissioning for the first time, whilst enabling more established providers to test the effectiveness of new and innovative types of provision.

For people living well with dementia, such a system would make it very easy for GPs to refer people to services to promote living well. Instead, GPs have needed to reach for their prescription pad to prescribe drugs which may have a modest effect on symptoms for a few months, but which have no effect on slowing progression.

Of course, it is in a sense sad that doctors have to accept parity of such interventions to promote living well with dementia by the symbolic prescription pad, but such formality may assist in commissioning and catalysing change towards the mindset of whole person care.

Whole person care, or integrated care in the alternative, is likely to be introduced by the incoming government of whatever political flavour after May 7th 2015. Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has already indicated that he will making the existing structures ‘do different things’ to avoid another massive structural reorganisation. However, in this new Jerusalem, it is likely that Health and Wellbeing Boards will take on a new importance.

People are still uncertain how whole person care would be implemented, but the money is probably on unified personal budgets being option. The concern for many is that the money would quickly run out in such budgets, and hybridising two systems (one universal and one means-tested) would undermine the founding principles of the NHS.

Notwithstanding, the current political intention from Burnham and Labour is for social care to become subsumed under the NHS.

Interventions which genuinely improve somebody’s quality of life for living well with dementia, such as reminiscence (including ‘Sporting memories‘), healthy living clubs, advocacy, life story, may find themselves empowered in the middle of 2015 in a way that they were never under the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” of the current administration.