Let’s for the sake of brevity keep the definition of ‘stigma’ short – but of course it has to be attempted in some way.

Stigma, according to the current Oxford English Dictionary is defined as follows firstly.

“A mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person:the stigma of mental disorder to be a non-reader carries a social stigma.”

One of the issues about human rights is that you can’t ‘pick and mix’ human rights. You have to take the full package. You can’t buy into some, and not the others. They apply to everyone however.

In vogue at the moment is a ‘rights based approach’, but, since mooting the issue, Daniella Greenwood (who is here at the ADI Conference 2015) voiced some concern it could encourage a checklist approach.

Checklists are essentially useful, I feel, as the information in them, and can provide inappropriate totality.

Like ‘person centred care’ (the phrase that is), the operationalisation and marketing can obfuscate the real sentiment.

For example, prior to the necessary legislation, racial discrimination was lawful in South Africa, so Gandhi was the ‘boat rocker’ to use modern NHS slang.

There was nothing on the checklist about racial discrimination so notionally it was not a legal issue.

Freedom of expression is a human right, article 10 in the English jurisdiction.

It immediately for many conjures up the famous saying,

“I do not agree with what you have to say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.” ― Voltaire

Along with #JeSuisCharlie and other horrific incidents, there has been further scrutiny of the wider operation of this right.

Take for example this, “The Right To Offend? Mehdi Hasan Denies ‘Absolute Right’ To Freedom Of Speech”.

” Speaking opposite Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a HuffPost/Polis debate, on the right to offend, Mr Hasan argued free speech was being “fetishized” and claimed many free-speech campaigners in the west were guilty of “brazen hypocrisy.”

“How can you construct a civilised, cohesive society if we go round encouraging everyone to insult each other willy nilly? Yes we do have a right to offend but it’s not the same as having a duty to be offensive. You have a responsibility not to go out of your way to piss people off. I have the right to fart in a lift, but I don’t do it because it is offensive.

“Some people want the right to be offensive but then get cross when people are offended.” “

There are various ways in which ‘dementia’ has become medicalised, which has supported the power of the medical profession over others in discourses, arguably. In the 1960s, warehousing of people with problems with mental health meant that drugs could be easily delivered. “Living better with dementia” in the community would’ve have been unheard of.

When Robin Williams took his own life, and who had been diagnosed with a dementia, immediately the potential for media explosion was commenced.

This subject combined two taboos – “dementia” and “suicide”.

Take for example this Daily Mail article entitled, “Robin Williams’ suicide was triggered by hallucinations from a devastating form of dementia”.

The article soon reveals,

“Court documents obtained by TMZ reveal that Williams, who was found hanging from a belt at his home in California last August, was suffering from dementia with Lewy bodies.”

Whether someone ‘suffers from dementia’ has been revisited numerous times, and I don’t intend to cover it here.

But the starting point, I feel, is that the stigma surrounding dementia goes a long way to explaining why people who have received a diagnosis of dementia don’t want to tell people about the diagnosis: sometimes called “coming out” with the diagnosis, to reflect perhaps a secret that could be hidden.

In response to Williams’ death, in the blog “Humanist Voices”, “Mental Illness: Stigma, Silence, Suicide — or Support?” Audrey in September 2014 had the following to say:

“Mental illness need not define a person as it often has in the past, but we have a long way to go to truly help those in need. Over the centuries, we as a society have ostracized, ridiculed, imprisoned, institutionalized, over-drugged, shamed, blamed, stigmatized and forgotten those who struggle with diseases of the mind. Quite unlike the history of physical ailments — which has had a distinctly different and more promising trajectory. Today we like to think we have a more enlightened view of mental illness, but countless people still fear the stigma of “coming out” with their mental health “issues” to peers and colleagues. How many among us try to hide our own struggles or those of our family members?

In the last half century society has moved away from overcrowded and often abusive mental institutions or asylums to a more humane community-based mental health approach. However, neither public funding nor insurance plans have ever provided the necessary support and resources to make such programs very effective. In fact, the lack of adequate community mental health services has given rise to jails and prisons becoming warehouses for the mentally ill in recent years. Even Minnesota faces a shortage of providers and hospital beds for those with serious mental illness as a recent legislative roundtable in west-central Minnesota revealed. And since William’s (sic) death, local media outlets such as Minnesota 2020 and MPR have been shining a light on the growing need for more mental health services across the state.”

So here we have one argument – that stigma is exacerbated by people not wanting to talk about their dementia diagnoses (“under expression”). Or, in the alternative, people feel bombarded with negative memes about dementia, e.g. “suffering”, “horrific”, “tsunami” or “time bomb”, in the general media. In any case, it can easily be argued that freedom of expression is a right that needs defending now as much as ever; it is therefore important to argue, say, freedom of expression “is the cornerstone of democracy, a vital foundation for tolerant societies.”. As this Amnesty International blogpost goes onto say, “According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 61 journalists were killed last year in direct reprisals for their work. The most dangerous country was, unsurprisingly, Syria. Just over a week into 2015, and the CPJ’s figure is already at five. The most dangerous country? France.”

But is the content of the media something we should take some notice of?

Yes – for a start the ADI Conference has language guidelines.

According to Miriam Bar-on (2000), in the USA, ” based on surveys of what children watch, the average child annually sees about 12 000 violent acts,5 14 000 sexual references and innuendos,6 and 20 000 advertisements.”

Television has the potential to generate both positive and negative effects. It turns out that an individual child’s developmental level is a critical factor in determining whether the medium will have positive or negative effects. Current literature suggests that perhaps physicians can change and improve children’s television viewing habits, or even excessive television watching contributes to the increased incidence of childhood obesity?

And interpretation of language is not new.

According to the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, “Hermeneutics” is defined as follows:-

“The term hermeneutics covers both the first order art and the second order theory of understanding and interpretation of linguistic and non-linguistic expressions. As a theory of interpretation, the hermeneutic tradition stretches all the way back to ancient Greek philosophy. In the course of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, hermeneutics emerges as a crucial branch of Biblical studies. Later on, it comes to include the study of ancient and classic cultures.”

Kate Swaffer, Co-Chair of the Dementia Alliance International and living with a dementia, argued this recently in Dementia Journal in an outstanding paper.

“It is therefore imperative that we aspire to change views of and about people with dementia, and begin to include them in the research and conversations about them. [Ken] Clasper (2014) writes a blog about living with dementia, and said: ‘…we wish to raise awareness of dementia, is that we all live on hope, that we can in our own little way go a long way to remove the stigma which we hear of every day in dementia’.”

So this is a case of ameliorating under-expresssion of information, consistent with the notion that prejudice and discrimination arise from lack of information and/or ‘lack of changing your mind’ when presented with new information.

And Kate explains, why despite Voltaire, it is in fact a big deal to be offended,

“Whilst, we may have changed, we are all there. Whilst we may in fact suffer, many of us are not sufferers, and find that term offensive. We no longer refer to people with physical or intellectual disabilities as retarded or as retards, as it is offensive to them, even though technically they [we] are retarded. I place myself in the disabled category, as I have many disabilities caused by the type of dementia I have. Technically, people with dementia are ‘demented’ too; however, most of us find that and other terms offensive, and have a right to stand up and speak out about it.”

I have seen with my own eyes how the medical profession culturally in an institutionalised way harbour anti-dementia memes like “demented” when talking with other doctors. I’ve been on ward rounds where the Consultant has turned to junior medical staff, with the person with advanced dementia waiting to be discharged after an operation, and said, “But don’t worry about him as he’s got dementia”.

We have furthermore to be extremely careful or vigilant that the global policy of “dementia friendly communities” does not promote a sense of ‘otherness’, defeating the prime objective of inclusive.

Swaffer (2014) warns:

“The determination by governments and Alzheimer’s societies and organizations around the world to promote dementia friendly communities and dementia champions still mostly supports the ‘about them, with them’ position, which has the potential to further stigmatize people with dementia. To date, only a few people with dementia have been included in the discussions, planning and decisions about what makes a community or organization dementia friendly.”

But there’s little doubt in my mind that dementia friendly communities is a valuable concept, even if the nosology isn’t quite right?

Danielle White from Alzheimer’s Australia NSW hopes that “understanding of the condition will turn into action”, a similar if not identical to the sentiment behind the UK’s “Dementia Friends” initiative.

She has said: “These figures show why it’s so important for us all to look at how we can create communities where people living with dementia are included, respected, valued, and supported to maintain a good quality of life.”

In a paper entitled, “Dementia Discourse: From Imposed Suffering to Knowing Other-Wise”. Gail J. Mitchell, Sherry L. Dupuis, and Pia C. Kontos, this intriguing diagram pops up on page 12 which I felt was a useful summary infogram about the ecosystem of a stigma.

Venance Dey has said that, “awareness about the disease was almost non-existent in Ghanaian communities hence the formation of the AG to raise awareness about dementia in local communities that would encourage government to build systems for all those affected to have access to quality care and support they needed.”

But we should care about the age at which stigma memes might get implanted.

Psychologist Dr Jess Baker has for example in Sydney’s west observed a group of Scouts watching DVDs about dementia. The video forum is part of a UNSW-led project that aims to create a more dementia-friendly society by educating the next generation. Information gleaned from the children will be used to develop an online education program, designed to align with Australia’s education curriculum.

.“We know that children are more responsive than adults to anti-stigma education because their beliefs are not as firmly developed,” according to Dr Jess Baker.

But the impact of mass media and popular culture should not be underestimated. A group of 11–14 year olds interviewed for a British dementia study made repeated references to the “dementors” in the Harry Potter movie series – half-dead creatures that feed on happy thoughts and memories leaving their victims in a mindless state.

According to Wikipedia,

“Rowling, by her own account, created the dementors after a time in which she, in her own words, “was clinically depressed”. Dementors can therefore be viewed as a metaphor for depression.”

First problem – the confusion between depression and dementia. Indeed, some depression might get confused as dementia (or vice versa); but there is a co-morbidity between depression and dementia.

“Despite their attachment to human emotion, dementors seem to have difficulty distinguishing one human from another, as demonstrated by Barty Crouch Jr.’s escape from Azkaban, wherein they could detect no emotional difference between the younger Crouch and his mother.”

Having abnormal emotional responses can be a feature of the frontotemporal dementias. Indeed, Prof John Hodges from NeuRA and Prof Simon Baron-Cohen have both been very interested in how the neural circuitry involved in reading others’ minds might go awry in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia.

“The dementors are “soulless creatures… among the foulest beings on Earth”: a phantom species who, as their name suggests, gradually deprive human minds of happiness and intelligence. They are the guards of the wizard prison, Azkaban, until after the return of antagonist Lord Voldemort.”

source Melissa (30 July 2007). “J.K. Rowling Web Chat Transcript – The Leaky Cauldron”. The-leaky-cauldron.org.

In popular culture, dementia is often portrayed as robbing people of their happiness.

“The presence of a dementor makes the surrounding atmosphere grow cold and dark, and the effects are cumulative with the number of dementors present. The culmination of their power is the ‘Dementor’s Kiss’, wherein the dementor latches its mouth onto a victim’s lips and consumes its soul or psyche, presumably to leave the victim in a vegetative state.”

And of course there are people like me who feel that your “Self” is not “robbed away from you” during dementia.

And finally,

“Beneath the cloak, dementors are eyeless, and the only feature of note is the perpetually indrawn breath, by which they consume the emotions and good memories of human beings, forcing the victim to relive its worst memories alone.”

Emotional regulation is affected quite late on in Alzheimer’s disease because of the usual time path of the condition, but the analogy of which memories are “robbed first” does not even correspond to actual life – in actual life, in the dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, recent memories go much earlier than later memories (the “so called temporal gradient”), and in fact worst memories might be emotionally charged such that they’re actually very vivid (a similar phenomenon happens with the effect of the stress hormone cortisol on memory formation.)

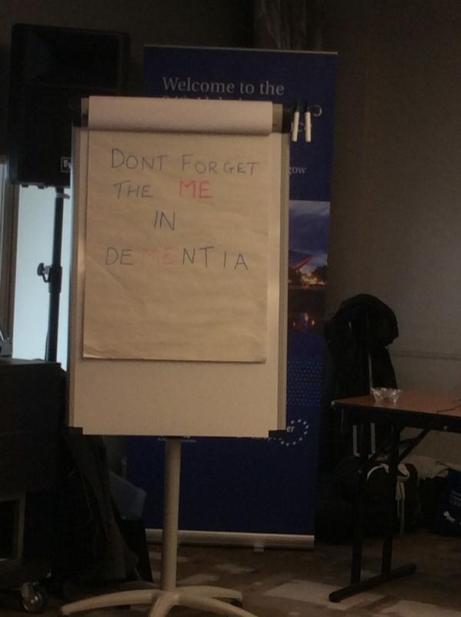

If we ‘go’ with the “rights based approach”, it’s pretty likely we’ll have to take ‘the full package’, which includes freedom of expression conversing with a person with dementia but also a freedom of expression of a person with dementia. Except…. there’s a catch here. If somebody’s acting badly with a person with dementia, it might be ‘freedom of expression’. If the person with dementia dares to say something back, it ends up being ‘agitation’, ‘aggression’ or ‘challenging behaviour’.

It essentially is a finely balanced deck of cards, where it just takes one thing to make the whole thing come crashing down.

Reading

Bar-on, M.E. (2000) The effects of television on child health: implications and recommendations, Arch Dis Child 2000;83:289-292 doi:10.1136/adc.83.4.289.

Swaffer, K. (2014) Dementia: Stigma, Language, and Dementia-friendly Dementia 2014 13: 709