I have some personal form on this. At the beginning of 2007, I was physically able bodied. At the end of 2007, I was learning how to walk and again, getting used to a new physical disability.

I do feel that anything can happen to anyone at any time. It just happens to be my experience that the nastiest of events can happen to the nicest of people (and the opposite is probably true too.)

It is a useful art to know how you personally would react to the unexpected. It’s well known that personal views of immortality and invincibility wane with time, even if they lag behind a temperance of personal ambition.

I attended yesterday an afternoon in a pleasant church in Wimbledon, to celebrate the launch of the Dementia Pathfinders document “Approaching an unthinkable future”. Having now read this original contribution, I do very strongly recommend it.

I took along a copy of my own book to give as a present to someone, so please forgive me for the gratuitous product placement.

This booklet is in two parts: what a diagnosis of young onset dementia has meant to recipients of that diagnosis in terms of getting on with their lives thereafter, and, secondly, how needs of people with young onset dementia are (or are not) met.

The afternoon was stimulating and refreshing.

The panel discussion consisted entirely of people “living beyond a diagnosis of dementia” (a term coined by Kate Swaffer, leading advocate and co chair of the Dementia Alliance International) and those closest to them. As before, many whom would be perceived as ‘carers’ by others did not see themselves as carers. It was later remarked that co-production lies at the heart of all of Dementia Pathfinders’ work from start to completion.

The contributions were candid, thought provoking and, most of all, useful – they all involved with lives affected by dementia personally.

It was lovely to see Keith and Rosemarie Oliver there. I chatted with Keith for some time. Keith like me is very keen on society hearing about personal narratives (and I should like to commend this new book by Lucy Whitman from my publishers). Also, Keith like me is to keen to tell the world about cognitive treatment approaches in dementia as, for example, advanced by the British Psychological Society faculty for older people.

It was also lovely to see again Peter Watson, of whom I have fond memories from the Dementia Action Alliance Carers Call to Action.

And of course Suzy Webster – simply great company, and a true ‘expert by experience’ for care (Suzy’s geographically on the far right of this picture.)

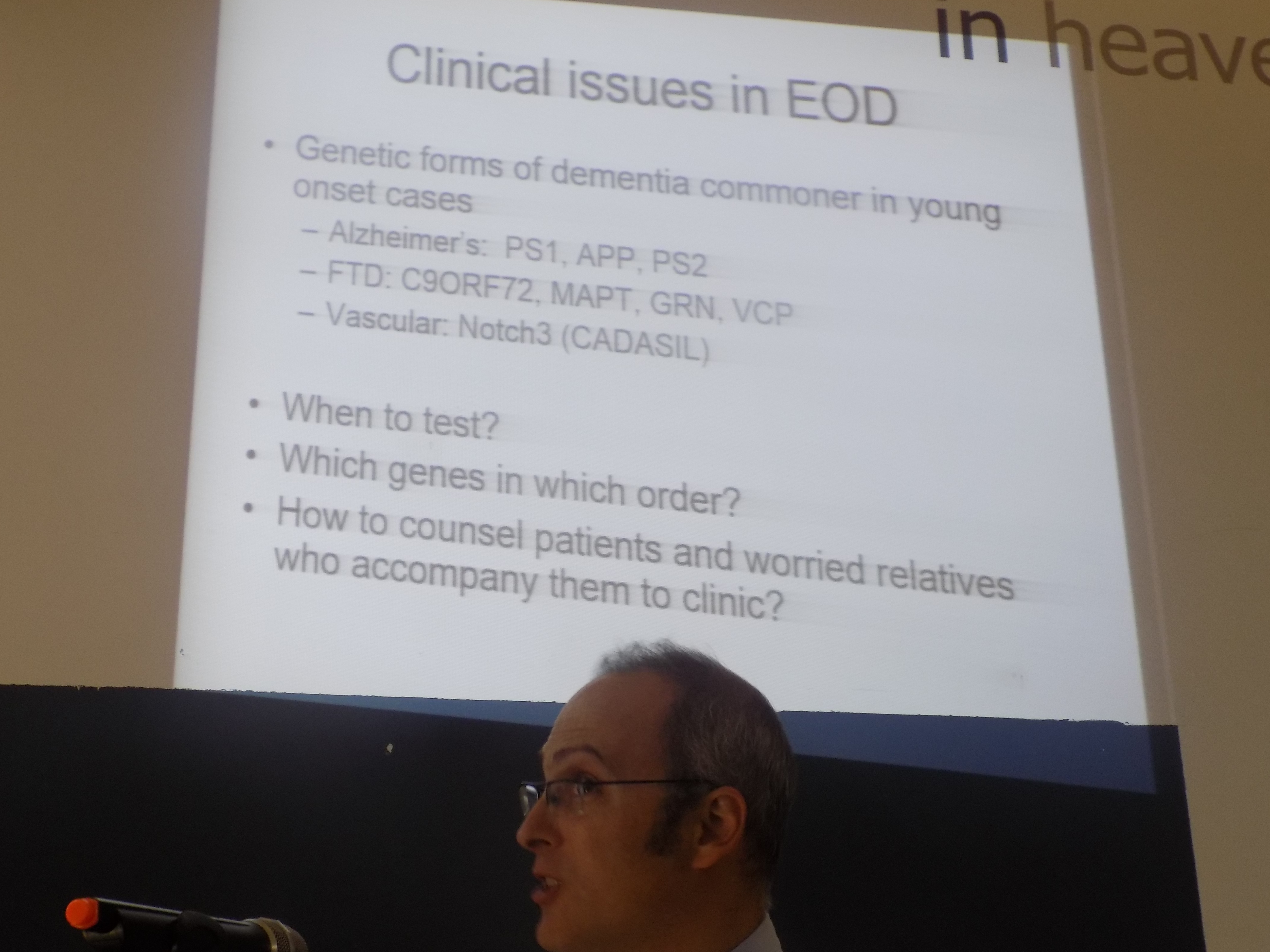

Dr Jeremy Isaacs gave an excellent overview of young onset dementia. I immediately recognised a slide of his Consultant colleague, Dr Peter Garrard, as he’d been at Cambridge under my own PhD supervisor, Prof John Hodges, and had been on the dementia and cognitive disorders firm at Queen Square under Prof Martin Rossor at the same time I had been there in the early 2000s.

In fact Peter’s work is directly related to one of the questions which was asked about how might the worried well prevent dementia. It’s my view that the best of the previous work has been equivocal (see the EClipSE study paper in Brain 2010); but clearly more research is needed. Peter had been involved in the seminal research studies in language breakdown in some forms of temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Iris Murdoch, married to Prof John Bayley, Emeritus Professor of English at Oxford, was indeed highly educated – and developed dementia.

On a different note, it was very nice to be in Oxford on the day previous to that to learn of the work of Young Dementia UK. I also had a terrific time visiting the Ashmolean Museum there.

Here are Barbara Stephens, CEO of Dementia Pathfinders, and Dr Jeremy Isaacs at the beginning of the event.

I was pleased to witness the overall direction of travel, as explained in Jeremy’s initial summary slide.

In no way do I wish to undermine the excellent work being done into the genetics of young onset dementia. Understanding the products of these faulty genes is a big step towards developing innovative drugs one day in the future. I dare say, with enough motivation and resources, it might be possible to identify those people who are particularly at risk – say for example those people with a very strong history for the presence and manifestation of particular genes – and use new drugs as a way of slowing down the build up of the products of these faulty genes.

But I do think EEG (measuring brain waves) can have a particular role to play in say determining whether the process a person presents with in ‘memory clinic’ is indeed a dementia (loss of particular rhythms), and indeed whether some brain wave patterns are that of rapidly progressive dementias such as Creutzfeld Jacob.

I am mindful of the service as a whole, so Jeremy’s point that the national campaign had sustained memes like ‘are you worried with your memory?’ such that many people with other causes of memory problems, for example depression, were coming to be assessed in memory clinic. I know also the converse is true – many people come to the memory clinic as the GP felt dementia had to be excluded but such people show neuropsychiatric symptoms including depression and anxiety. And some of them do later develop a full picture of a dementia.

As Jeremy correctly said, many of the young onset dementias do not indeed present with profound memory loss. I am mindful of the behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia – the subject of my own PhD – heralded by changes in personality and behaviour typically. Another example is posterior cortical atrophy – where the initial problems can be in fact perception of objects, judging depth and so on. Also memory can be quite good, although variable from day to day, for many people who’ve just received a diagnosis of diffuse Lewy body dementia.

This is a legitimate question of national policy therefore, where the overall drive appears to be increasing the dementia rates. But one has to presume that there are sufficient resources in diagnosing young onset dementia with an adequately skilled workforce. The figure for the prevalence of young onset dementia varies – it’s around 40,000 – but I suspect due to the lack of timely diagnosis – the figure is in fact much higher. Jeremy lamented that every doctor should be able to do a good bedside cognitive assessment – and I share this sentiment.

I did say to Jeremy before the event that the philosophy of many doctors did seem to be that not much could be offered through the prism of the ‘prescription pad’. I can immediately think of a whole host of issues which merit discussion beyond the diagnosis: such as employment, housing arrangements, creativity clubs, personal relationships, finances, and other social networks and events.

The diagnosis can be profoundly isolating. Professionals without having organisations to turn to (such as Dementia Pathfinders). It’s my view that many feel that they have no one to turn to other than brilliant organisations such Young Dementia UK. There’s no doubt that third sector organisations, including social enterprises, have a huge role to play in increasing the capacity of services for dementia, as indeed I once argued in the Health Services Journal.

I am sure that there’s a conversation yet to be had about ‘age appropriate services’. Views on this vary: for example, one person living with dementia told me that you wouldn’t mix children with adults on wards, and residential settings should be no exception; on the other hand, another person with young onset dementia, said that having young-only services is ageist in itself, he doesn’t mind talking to people much older people, and he said on principle the difference between 55-65 should not be any different to 65-75 or 75-85 and so on.

Equally critical is the question of how to enhance health and wellbeing regardless of care setting – how to get people in and out of hospital safely and in a timely way is now becoming a burning issue. Dominique Kent’s presentation was superb.

I’m still of the view that anything can happen to anyone at any time. Regardless of the precise ‘care setting’, all persons with dementia do deserve access to the very best standards in NHS healthcare too. And as many people pointed out yesterday the community not only has to be ‘friendly’ or indeed supportive but actually need to be educated in what dementia is. Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of many of us, we’ve still got a long way to go (although it’s fair to say we have come a long way).