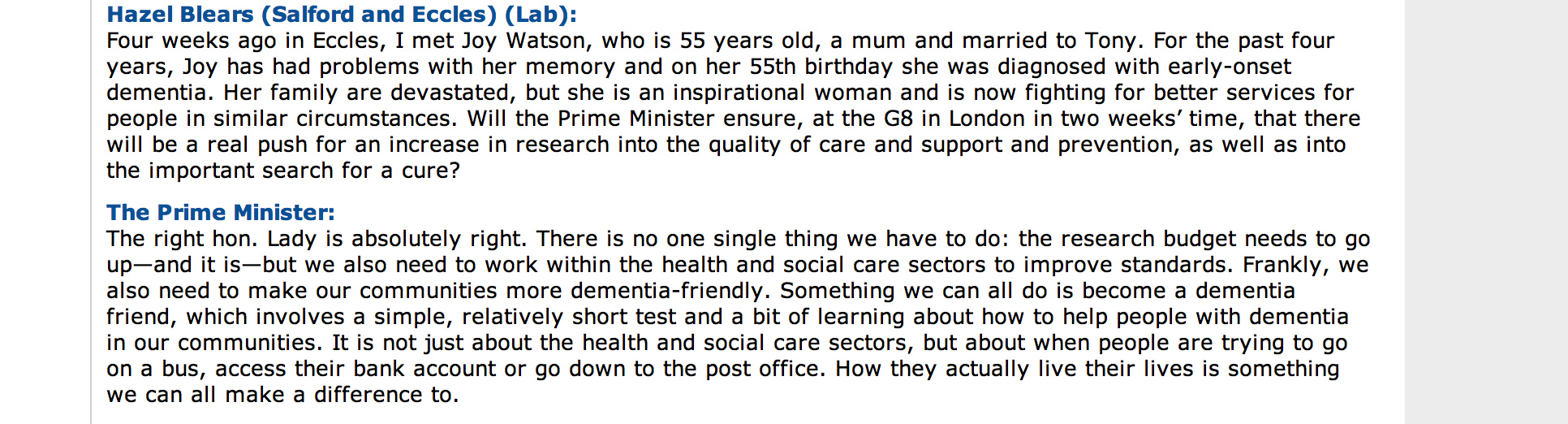

There is a strong sense from the National Dementia Strategy (2009) of the need for individuals living well with dementia to be part of a wider network which creates higher shared value. The establishment and maintenance of such networks will provide direct local peer support for people with dementia and their carers. It will also enable people with dementia and their carers to take an active role in the development and prioritisation of local services There is, however, a growing realisation that many settings are not in fact “dementia friendly”. In the Department of Health’s “Improving care for people with dementia”, it is described that a quarter of hospital beds are occupied by people with dementia. To improve health and care services for people with dementia, by March 2013 the current English policy is committed asking every hospital in England to commit to becoming dementia-friendly. Indeed, the UK Government reported in “Improving care for people with dementia”, on the UK government website 25 March 2013 that ‘dementia friendly communities’ are a key priority.

It is argued that it will take time for communities to become truly dementia friendly. Groups in over 20 areas, that have now committed to working towards becoming dementia friendly villages, towns and cities. As we develop a process and criteria for developing dementia friendly communities we expect this number to grow. For example, at the time of writing, thirty new members have signed up to the Dementia Action Alliance (DAA), taking the number of bodies and organisations to over hundred. Each organisation has produced an action plan on what they will do to become more dementia friendly. The DAA is a membership body committed to transforming the quality of life of people living with dementia in the UK and the millions of people who care for them.

Context

People with dementia and carers have described seven outcomes that must be met to ensure that they live well with the condition (Dementia Action Alliance).

The history of this “declaration” is summarised thus:

“Working in partnership with the initial signatories, people with dementia and their family carers described seven outcomes they would like to see in their lives. They provide an ambitious and achievable vision of how people with dementia and their families are supported by society. All individuals and organisations, large and small, can play a role in making it a reality.”

The elements are:

- “I have personal choice and control or influence over decisions about me”

- “I know that services are designed around me and my needs”

- “I have support that helps me live my life”

- “I have the knowledge and know-how to get what I need”

- “I live in an enabling and supportive environment where I feel valued and understood”

This work, alongside other research on quality of life for people affected by dementia, shows that many issues influence how well people live, from health and social care, to social relationships, engagement in activities, a sense of belonging and of being a valued part of family, community and civic life. Other work also highlights the importance of society and developing age-friendly environments.

Domestic and international context

The RSA’s “Connected Communities” project describes itself as, “multi-faceted comprising several interrelated research projects, through which we aim to gain a better understanding of the conditions under which a new civic collectivism, or social productivity, may emerge – one that is organic, spontaneous, and bottom-up.”

The WHO “age friendly communities” or “age friendly cities” initiative is also very significant. In 2008, for the first time in history, the majority of the world’s population lived in cities. Urban populations will continue to grow in the future. It is estimated that around 3 out of every five people will live in an urban area by 2030.At the same time, as cities around the world are growing, their residents are growing older. The proportion of the global population aged 60 will double from 11% in 2006 to 22% by 2050. According to WHO, making cities and communities age-friendly is one of the most effective local policy approaches for responding to demographic ageing.

According to WHO:

The physical and social environments are key determinants of whether people can remain healthy, independent and autonomous long into their old age.

Older persons play a crucial role in their communities – they engage in paid or volunteering work, transmit experience and knowledge, and help their families with caring responsibilities. These contributions can only be ensured if they enjoy good health and if societies address their needs. The WHO Age-friendly Environments Programme is an international effort to address the environmental and social factors that contribute to active and healthy ageing. The Programme helps cities and communities become more supportive of older people by addressing their needs across eight dimensions: the built environment, transport, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication, and community support and health services.

This World Health Organisation initiative appears to provide an international network of good practice in these areas and opportunities to connect the growing number of places interested in dementia-friendly communities to this work. For example, it is argued that domestically here in Manchester, long-term involvement of older people in planning the development of the city at urban and neighbourhood levels has improved the physical and environmental access for older people, raising their confidence and empowering them to become involved in decision-making.

Social inclusion is becoming, of course, increasingly achievable through online social networks. Shirley Ayres (2013) argues in a ‘provocation paper’ for Nominet that social exclusion, loneliness, managing health and disabilities, and unemployment are big issues for society generally. The problems for older people can be exacerbated by ill health, significant life changes such as retirement and transitions – which may require moving to supported living – and the death of partners and close friends. Retaining a sense of worth and value, keeping connected to family and friends, and continuing to contribute to society are important considerations in addressing social inclusion.

What is a “dementia friendly community”?

The definition of the word ‘community’ itself is problematic and in this paper we have used it both thematically (e.g. ethnic or spiritual group, specific interest group, club or society) and geographically to reflect the various domains

of people’s lives. People with dementia in this project and in others that members of AESOP Consortium (an organisation that advises local health and social care systems on reform) have been involved with (Local Government Association, 2012) have described a dementia-friendly community as one that enables them to:

- find their way around and feel safe in their locality/community/city;

- access the local facilities that they are used to (such as banks, shops, cafés, cinemas and post offices, as well as health and social care services);

- maintain their social networks so they feel they still belong in the

community.

Furthermore, a society or community that acts consciously to ensure that people with dementia (along with all its citizens) are respected, empowered, engaged and embraced into the whole is one that can claim to be, or is becoming, a dementia-friendly community. We have reflected that there are similar movements for communities currently to become generally more ‘age-friendly’, just as more recently they consciously became more ‘child-friendly’ and ‘wheelchair-friendly’. As mentioned in chapter 16, dementia comes within scope of the Equality Act [2010], and this therefore is an important legal consideration now.

Communities that aspire to become dementia-friendly are likely also to be those that constantly strive to build social capital and community capacity for all their local populations of residents, workers and visitors and, in doing so, value the contribution that each makes. This may be summarised by the phrase ‘an assets-based approach’, that is, one that builds on what people can still do, as opposed to a ‘deficit-model’ that focuses on what people can no longer do and somehow ‘reduces’ them because they cannot contribute to society more fully. Appreciating the whole person – in line with Kitwood’s (1997) development of the notion of personhood – and their valuable individual contribution to the “citizenry” of a place, community or society is

an aim of this project and of the whole of Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s programme of work on dementia and society.

Community development progresses this aim; civic engagement and increased social capital are its outputs. Mutual gain for everyone is the outcome.

In Europe, Bruges is leading the way in an expanding movement of towns and cities that are championing the dementia-friendly approach, which include Nantes in France and Ansbach in Germany. Bruges’ knotted red handkerchief logo signifying “dementievriendelijkBrugge” (“dementia-friendly Bruges”) is being taken up by other organisations and countries and they welcome others using the logo too, to increase its chances of becoming a universally recognisable emblem.

Where did the concept of “dementia friendly communities”come from?

Growing awareness of the demographic changes in the population as the proportion of older people and the prevalence of dementia increase has prompted research and policy development in both age-friendly and dementia-friendly communities.

In 2011, the Department of Health convened a ‘Think Tank’ of experts, including people with dementia and family carers, to explore the concept of “dementia-capable communities”. In preparation it commissioned Innovations in Dementia to work with people with dementia to find out what makes a good community for people with dementia to live in and what can be done to make this happen (“Dementia Capable Communities” from “Innovations in Dementia”).

They found that the things that make the most difference are:

- the physical environment;

- local facilities;

- support services;

- social networks;

- local groups.

People with dementia suggested that things could be made better by:

- increasing people’s awareness of dementia;

- having more local groups for people with dementia and their carers;

- providing more information, and more accessible information, about local services and facilities;

- making local facilities more accessible for people with dementia.

Why encourage ‘dementia friendly communities’?

1. The growing numbers of people with dementia

All statutory agencies should be familiar with the public health and demographic changes occurring over the next generation, including a doubling of the numbers of people with dementia over the next 30 years and a shrinking of the working population to support those in later life. By 2019, 38 percent of the population will be aged over 50, and by 2029 this will have risen to 40 percent (Audit Commission, 2008).

2. The economic arguments

In the U.K., the economic climate had

driven significant cuts in public sector spending that have impacted on commissioners’ abilities to fund services adequately or to invest in future service provision. It has also unfortunately coincided with the formation of different health commissioning arrangements; the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and the Health and Wellbeing Boards, both still in their transitional infancy, are too new to have had much impact yet. Arguably, the growing elderly population is a source of spending power that has been overlooked in the past in favour of younger people with apparently more cash to spend.

3. The value of independence and interdependence

The people we met told us that the most distressing part of their illness is that, after a lifetime of autonomy and self-determination, they find themselves having to rely increasingly on others. Even when they recognise that they need help, they are sensitive to

the complexity of nuance and understanding which can be felt on both sides.

4. The wish to remain connected to communities

Highest on the list of difficulties for people with dementia are the everyday community activities that everyone else takes for granted, such as withdrawing money at the bank, paying bills, shopping and using public transport. Trying to carry on daily life as before becomes more difficult and problematic for people. As a result they start to feel disconnected from their old groups, friends, activities and places.

5. The interconnectedness of community life

Research and anecdotal reports of people’s personal accounts converge on the notion that receiving a diagnosis of dementia is a major life event. Fear and ignorance of dementia among family and friends, as well as the general population, may mean

that others respond negatively. Many report, in addition, reveal a necessity to make new friends, commonly from the dementia community, as they begin to lose friends and connections in their old walks of life.

6. The need to create inclusive local communities

Older people are fellow citizens who should be able to participate in local communities and benefit from universal services to the same extent as other age groups. Scrutinising local mainstream and universal services through an age-proofing lens benefits not only older people but also many other groups – younger people, families with children, wheelchair users and other disabled groups (Audit Commission, 2008). Older people should have a stake in how universal services such as transport, parks and gardens, refuse collection and leisure services are planned and organised. Finally, through better use of space and the increased use of technology, more older people are able to participate more fully in society. The Independent featured in its reporting the impact of ageing on city life in the future, signalling the growth of environmental gerontology.

Why involve individuals with dementia in the design of ‘dementia friendly communities’?

The Local Government Association and ‘Innovations in dementia’ have explained why it is so essential to listen to the views of those individuals with dementia.

The idea of making our communities better places to live for people with dementia is something which engages the enthusiasm and interest of all sorts of people. Traders, leisure companies, transport providers, planners, service providers, health and social care organisations, charities are all potentially affected; all have a role to play in forming a vision about what a dementia-friendly community should look like.

The most important stakeholders in this process of course are people with dementia, and those who care for and support them.

“Nothing about us without us” is a slogan which carries great resonance for disability rights campaigners – and is one which is increasingly being articulated by people with dementia as well. The voices of people with dementia and their carers should be at the start and the heart of the process of creating dementia-friendly communities.

What do individuals with dementia appear to want from ‘dementia friendly communities’?

The Local Government Association and ‘Innovations in dementia’ have explained that it is important to listen to the expectations of individuals with dementia in formulating a policy on dementia-friendly communities.

Their findings are shown below.

“People told us about the things which make a difference in a dementia-capable community:

- the physical environment;

- local facilities;

- support services;

- social networks;

- local groups.

“People told us that they kept in touch with their local communities”:

- through local groups;

- through the use of local facilities;

- through walking;

- through the use of support services.

“People told us they had stopped doing some things in their community because: their dementia had progressed and they were worried about their ability to cope they were concerned that people didn’t understand or know about dementia.”

“People told us that they would like to be able to:

- pursue hobbies and interests;

- simply go out more;

- make more use of local facilities;

- help others in their community by volunteering.”

“People told us that one-to-one informal support was the key to helping them do these things.

People told us that a community could become more ‘dementia-capable’ by:

- increasing its awareness of dementia;

- supporting local groups for people with dementia and carers’

- providing more information, and more accessible information about local services and facilities;

- thinking about how local mainstream services and facilities can be made more accessible for people with dementia.”

The Four Cornerstones Model

Crampton, Dean, and Eley (and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation) in a report on building a dementia-friendly community in York present an elegant ‘four cornerstone’ model.

Their analysis of previous and parallel work, supported by our findings in York, led us to propose a model for realising a dementia-friendly community. With the voices of people at the heart of the process, it is argued that communities need to consider four ‘cornerstones’ to test the extent of their dementia friendliness. These are:

Place – how do the physical environment, housing, neighbourhood and transport support people with dementia?

People – how do carers, families, friends, neighbours, health and social care professionals (especially GPs) and the wider community respond to and support people with dementia?

Resources – are there sufficient services and facilities for people with dementia and are these appropriate to their needs and supportive of their capabilities? How well can people use the ordinary resources of the community?

Networks – do those who support people with dementia communicate, collaborate and plan together sufficiently well to provide the best support and to use people’s own ‘assets’ well?

The “socio-economic position”

The “socio economic position” (SEP) refers to the position of individuals in the hierarchy and is inherently unequal, shaping access to resources and every aspect of experience in the home, neighbourhood and workplace (Krieger 2001a; 2001b; Graham 2004; Regidor 2006). Different dimensions of SEP (education, income, occupation, prestige) may influence health through different pathways and so may be more or less relevant to different health outcomes. It is the extent to which SEP involves exposure to psychological (in addition to material) risks and buffers that is of special interest from

a mental health perspective. SEP structures individual and collective experiences of dominance, hierarchy, isolation, support and inclusion. Social position also influences constructs like identity and social status, which impact on wellbeing, for example, through the effects of low self esteem, shame, disrespect and ‘invidious comparison’ (Rogers and Pilgrim 2005; de Botton, 2004). Sen has previously argued that shame and humiliation are key social dimensions of absolute poverty and that the ‘ability to go about without shame’ is a basic capability or freedom (Sen, cited in Zavaleta 2007).

The use of the term psycho-social is important because it highlights the psychological/emotional/ cognitive impact of social factors, the effects of which need to be distinguished from material factors. For example, unemployment that leads to loss of income is not psycho-social, whereas

the loss of self esteem that accompanies unemployment is (Martikainen et al., 2002). Individual psychological resources, for example, confidence, self-efficacy, optimism and connectedness appear embedded within social structures: our position in relation to others at work, at home, and in public spaces. Because social position influences emotion, cognition and behaviour, it is an ongoing challenge to separate out contextual effects (Singh-Manoux and Marmot 2005). Context was first introduced in chapter 9.

An example of making a community “dementia friendly”

Hampshire County Council, ‘Innovations in Dementia’ and the Local Government Association provide a very good example of steps through which a community can be made more ‘dementia friendly’. They cite that memory problems make life difficult, and suggest the following:

- people who understand about memory problems – this can be people in shops, bus drivers, friends and family or anyone you come into contact with;

- clear signposting, so people know where they are going and where things are;

- clearly-written information on things like bus timetables or leaflets about services;

- being able to spend time with other people in a similar situation;

- having someone to go with.

The benefits of “resilient communities”

A wide range of research demonstrates the health significance of social relationships and both formal and informal social systems as mediators of psychosocial stress resulting, for example, from inequality or economic transition. The relationship is not always clear cut (De Silva et al., 2005, 2007). There are different forms of community cohesion with different effects, in low income countries, for example, or for particular groups where strongly bonded communities may exclude minorities.

Nevertheless, communities with high levels of social capital, indicated by norms of trust, reciprocity, and participation, have advantages for the mental health of individuals, and these characteristics have also been seen as indicators of the mental health or wellbeing of a community (Morgan and Swann 2004; Lehtinen et al., 2005; McKenzie and Harpham 2006). The mental health of communities can be both a risk factor (e.g. the concept of social recession) and a protective factor (e.g. the application of herd immunity to mental health) (Stewart-Brown 2003). Hopelessness and a difficulty in imagining solutions, which are also risk factors for suicidal behaviour, are influenced by both neighbourhood culture and the physical environment.

For individuals, social participation and social support in particular, are associated with reduced risk of common mental health problems and better self reported health. Social isolation is an important risk factor for both deteriorating mental health and suicide (Pevalin, and Rose 2003; Social Exclusion Unit 2004). The key question is, perhaps, the extent to which social capital mediates the effects of material deprivation. Many studies have found that social support and social participation do not mediate these effects (Mohan et al. 2004; Morgan and Swann 2004). A recent ecological study of 23 high and low income countries found no significant association between trust and adult mortality, life expectancy and infant mortality. Rather the results supported the importance of both absolute and relative income distribution (Lindstrom and Lindstrom 2006).

This does not mean that neighbourhood effects are insignificant: we know that indicators of social fragmentation and conflict in communities, as well as high levels of neighbourhood problems influence outcomes independently of socio-economic status (Agyemang et al. 2007; Steptoe

and Feldman 2001). Mistrust and powerlessness amplify the effect of neighbourhood disorder, making where you live as important for health and wellbeing as personal circumstances (Krueger et al., 2004).

Socially disorganised areas provide a dangerous mix: large numbers of potential offenders who have few opportunities other than crime, many potential victims, and few social organisations or individuals who are capable of protecting others from violence (Krueger et al., 2004). Area level effects may be particularly significant for some causes of mortality: in Scotland, for example, increases in inequalities in mortality are driven by increases in death rates at a young age in areas of high deprivation, for example for liver disease, suicide and assault and mental and behavioural disorders due to drugs (Leyland, 2007).

It may be that negative symptoms of low morale and psycho-social vulnerability in communities, including anxiety, paranoia, aggression, hostility, withdrawal and retreat, have a greater power than protective factors, or, as we saw in relation to resilient places, that material resources outweigh other factors.

WEBSITES

Dementia Action Alliance, National Dementia Declaration. http://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/who_are_we/national_dementia_declaration

RSA: Connected communities

http://www.thersa.org/action-research-centre/public-services-arts-social-change/connected-communities

Department of Health: The Dementia Challenge Dementia friendly communities

http://dementiachallenge.dh.gov.uk/category/areas-for-action/communities/

WHO Global network of age-friendly cities and communities

http://www.who.int/ageing/age_friendly_cities_network/en/

Legislation

Disability Discrimination Act [2005]

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1995/50/contents

Equalities Act [2010]

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

REFERENCES

Agyemang, C., van Hooijdonk, C., Wendel-Vos, W., Lindeman, E., Stronks, K., and Droomers, M. (2007) The association of neightbourhood psychosocial stressors and self-rated health in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61, pp. 1042-1049.

Audit Commission (2008) Don’t stop me now: Preparing for an ageing population. Available at: http://www.cpa.org.uk/cpa/Dont_Stop_Me_Now.pdf.

Ayres, S. for the Nominet Trust (2013) Can online innovations enhance social care? http://www.nominettrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/Enhancing%20social%20care_PP_0113.pdf

Ayres, S. (2013) Click guide to digital technology in adult social care. [epub] Available at: http://www.lulu.com/shop/shirley-ayres/click-guide-to-digital-technology-in-adult-social-care/ebook/product-20730904.html;jsessionid=F772B09C305EF528BE72FFA61ED53371.

Crampton, J., Dean, J., and Eley, R. (on behalf of the ‘Joseph Rowntree Foundation) Creating a dementia-friendly York. October, 2012. Available at: http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/dementia-communities-york-full.pdf.

De Botton, A (2004) Status Anxiety. London, Hamilton.

De Silva, M.J, McKenzie, K., Harpham, T, Huttly SR. (2005) Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, pp. 619-627.

De Silva, M.J., Huttly, S.R., Harpham, T., and Kenward, M.G. (2007) Social capital and mental health: a comparative analysis of four low income countries, Social Science and Medicine, 64, 1, pp.5-20.

Department of Health (2009) Living well with dementia: A National Dementia Strategy: Putting people first. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/168221/dh_094052.pdf.

Department of Health (2013) Improving care for people with dementia. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/improving-care-for-people-with-dementia

Department of Health (2013) Improving care for people with dementia. Accessible at: https://www.gov.uk/government/policies/improving-care-for-people-with-dementia.

Friedli, L [on behalf of the World Health Organization: Europe]; National Institute for Mental Health in England, Child Poverty Action Group, Faculty of Public Health and Mental Health Foundation. (2009) Mental health, resilience and inequalities. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/100821/E92227.pdf.

Graham, H. (2004) Social determinants and their unequal distribution: clarifying policy understandings, Millbank Quarterly, 82, 1, pp. 101-24.

Hampshire County Council, Innovations in Dementia, Local Government Association. Making Hampshire a dementia-friendly county. Finding out what a dementia friendly community means to people with dementia and carers. April 2012. Acccessible at: http://www.innovationsindementia.org.uk/DementiaFriendlyCommunities/DementiaFriendlyCommunities_engagement.pdf.

Krieger, N. (2001a) Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century:

an ecosocial perspective, International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, pp. 668-677.

Krieger, N. (2001b) A glossary for social epidemiology,

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, pp. 693-700.

Krueger, P.M., Bond Huie, S.A., Rogers, R.G., and Hummer, R.A. (2004) Neighbourhoods and homicide mortality: an analysis of race/ethnic differences, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, pp. 223-230.

Lehtinen V, Sohlman B, and Kovess-Masfety V (2005) Level of positive mental health in the European Union: Results from the Eurobarometer 2002 survey, Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 1:9.

Lindstrom, C. and Lindstrom, M. (2006) Social capital, GNP per capita, relative income and health: an ecological study of 23 countries, International Journal of Health Services, 36, 4, pp. 679-696.

Local Government Association/Innovations in Dementia. Developing dementia-friendly communities. Learning and guidance for local authorities. May 2012. Available at: http://www.local.gov.uk/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=0a7a291b-d6a3-4df6-9352-e2f3232db943&groupId=10171.

Martikainen, P., Bartley, M., and Lahelma, E. (2002) Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology, International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6), pp. 1091-3.

McKenzie, K. and Harpham, T. (2006) Social capital and mental health, London: Jessica Kingsley.

Mohan, J., Barnard, S., Jones, K. and Twigg, E. (2004) Social capital, geography and health: developing and applying small-area indicators of social capital in the geography of health inequalities. In, Morgan, Antony and Swann, Catherine (eds.) Social capital for health: issues of definition, measurement and links to health. London, Health Development Agency, pp. 83-109. Accessible at: http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/documents/socialcapital_issues.pdf.

Morgan A. and Swann C (eds) (2004) Social Capital for Health: Issues of Definition, Measurement and Links to Health. London, Health Development Agency.

Pevalin DJ and Rose D (2003) Social capital for health: Investigating the links between social capital and health using the British Household Panel Survey. Wivenhoe: Institute for Social and Economic Research University of Essex. Accessible at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/documents/socialcapital_BHP_survey.pdf.

Regidor, E. (2006) Social determinants of health: a veil that hides socioeconomic position and its relation with health, Journal of Epidemiology and Health, 60, pp. 896-901.

Rogers, A. and Pilgrim, D. (2003) Inequalities and mental health. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Singh-Manoux, A. and Marmot, M. (2005) Role of socialization in explaining social inequalities in health, Social Science and Medicine, 60, pp. 2129-2133.

Social Exclusion Unit (2004) Mental Health and Social Exclusion: Social Exclusion Unit Report. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Available at: http://www.nmhdu.org.uk/silo/files/social-exclusion-unit-odpm-2004-social-exclusion-and-mental-health.pdf.

Spinney, L. (2013) Streets ahead: A revolution in urban planning. The Independent newspaper. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/streets-ahead-a-revolution-in-urban-planning-2024234.html.

Steptoe, A., and Feldman P.J. (2001) Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health, Ann Behav Med, 23(3), pp. 177-85.

Stewart-Brown, S. (1998) Public health implications of childhood behaviour problems and parenting programmes. In: Buchanan A, Hudson BL (ed.) Parenting, Schooling & Children’s Behaviour: Interdisciplinary approaches. Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing.

Zaveleta Reyles, D. (2007) The ability to go about without shame: a proposal for internationally comparable indicators of shame and humiliation. Working Paper 3. Oxford, University of Oxford. Accessible at: http://www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/OPHI-wp03.pdf