Would I want to know if I had a dementia?

The background to this is that I am approaching 40.

For the purposes of my response, I’m pretending that I didn’t study it for finals at Cambridge, nor learn about it during my undergraduate postgraduate training/jobs, nor having written papers on it, nor having written a book on it.

However, knowing what I know now sort of affects how I feel about it.

Dementia populations tend to be in two big bits.

One big bit is the 40-55 entry route. The other is the above 60 entry route. So therefore I’m about to hit the first entry route.

I don’t have any family history of any type of dementia.

My intuitive answer is ‘yes’. I’ve always felt in life that it is better to have knowledge, however seemingly unpleasant, so that you can cope with that knowledge. Knowledge is power.

If I had a rare disease where there might be a definitive treatment for my dementia, such as a huge build-up potentially of copper due to a metabolic inherited condition called Wilson’s disease, I’d be yet further be inclined to know about it.

I would of course wish to know about the diagnosis. The last thing I’d want is some medic writing ‘possible dementia’ on the basis of one brain scan, with no other symptoms, definitively in the medical notes, if I didn’t have a dementia. This could lead me to be discriminated against to my detriment in future.

There is a huge number of dementias. My boss at Cambridge reviewed the hundreds of different types of dementia for his chapter on dementia in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Properly investigating a possible dementia, in the right specialist hands, is complicated. Here‘s his superb chapter.

But just because it’s complicated, this doesn’t mean that a diagnosis should be avoided. Analysis can lead to paralysis, especially in medicine.

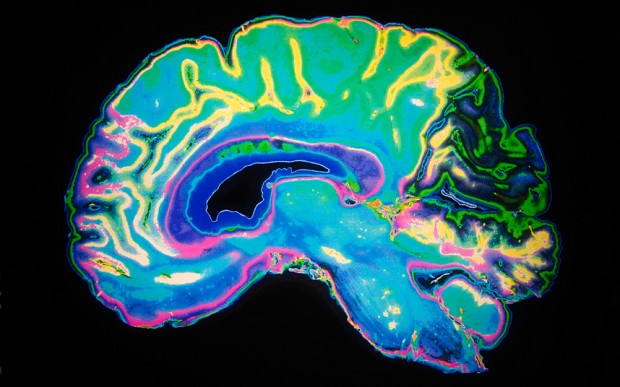

I very strongly believe that there’s absolutely nobody more important that that person who happens to living with a diagnosis of dementia. That diagnosis can produce a constellation of different thinking symptoms, according to which part of the brain is mainly affected.

I also think we are now appreciating that many people who care for that person also may have substantial needs of their own, whether it’s from an angle of clinical knowledge about the condition, legal or financial advice.

I think though honesty is imperative.

I think we need people including charities to be honest about the limitations and potential benefits in defined contexts about drug treatments for dementia. It’s clearly in the interest of big pharmaceutical companies to offer hope through treatments which may objectively work.

I think we also need to be very open that a diagnosis of dementia isn’t a one path to disaster. There is a huge amount which could and should be done for allowing a person with dementia to live well, and this will impact on the lives of those closest to them.

This might include improving the design of the home, design of the landscape around the home, communities, friends, networks including Twitter, advocacy, better decision-making and control, assistive technology and other innovations.

The National Health Service will need to be re-engineered for persons with a diagnosis of dementia to access the services they need or desire.

Very obviously nobody needs an incorrect ‘label’ of diagnosis. The diagnosis must be made in the right hands, but resources are needed to train medical professionals properly in this throughout the course of their training.

All health professionals – including physicians – need to be aware of non-medical interventions which can benefit the person with dementia. For whatever reason, the awareness of physicians in this regard can be quite poor.

There is no doubt that dementia can be a difficult diagnosis. Not all dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, characterised by symbolic problems in new learning. There are certain things which can mimic dementia for the unaware.

But back to the question – would I rather know? If the diagnosis were correct, yes. But beware of the snake oil salesman, sad to say.