Dementia is a very complex construct, embracing a number of different possible diagnoses, with different time courses. There is a common perception that ‘dementia’ is a single disorder, further perpetuated by most of the media, but this is far from true, and indeed a critical rôle of the cognitive neurologist might be try to identify what particular type of dementia an individual might be living with. This might best inform an approach to be taken by all specialties in helping that individual, and specific problems might be, for example, in wayfinding or social interactions at an early stage.

There are many different types of dementia, and they all tend to affect various bits of the brain as the disease progresses in a certain order. Whilst the patterns of progression are not identical, it can be observed that certain issues are more likely to met in some forms of dementia rather than others. For example, an individual with dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) is likely to have difficulty with spatial navigation or wayfinding earlier on, as the part of the brain affected in that type of dementia earlier one tends to be the areas around the hippocampus in the temporal lobe part of the human brain. Conversely, in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), individuals can be referred to health services because of a subtle change in personality and behaviour, with memory for day-to-day events relatively intact.

Any analysis of ‘living well in dementia’ has to acknowledge that dementia is a “heterogeneous” condition, and a specialist view of dementia will tend to consider specific issues which may be more relevant in the activities of daily living in any individual with dementia. This focused approach is likely to be a constructive one, to help society enable individuals with dementia with their distinct issues. If these issues can be addressed in a way that appreciates the individual as a person, rather than ‘medicalising’ the patient, the wellbeing of immediates (e.g. family or friends) is likely to be better too.

Dementia of Alzheimer type

Dementia of Alzheimer type is the most common cause of dementia and a growing health problem globally, affecting 20% of the population over 80 years of age (Ferri et al., 2005).

Pathology

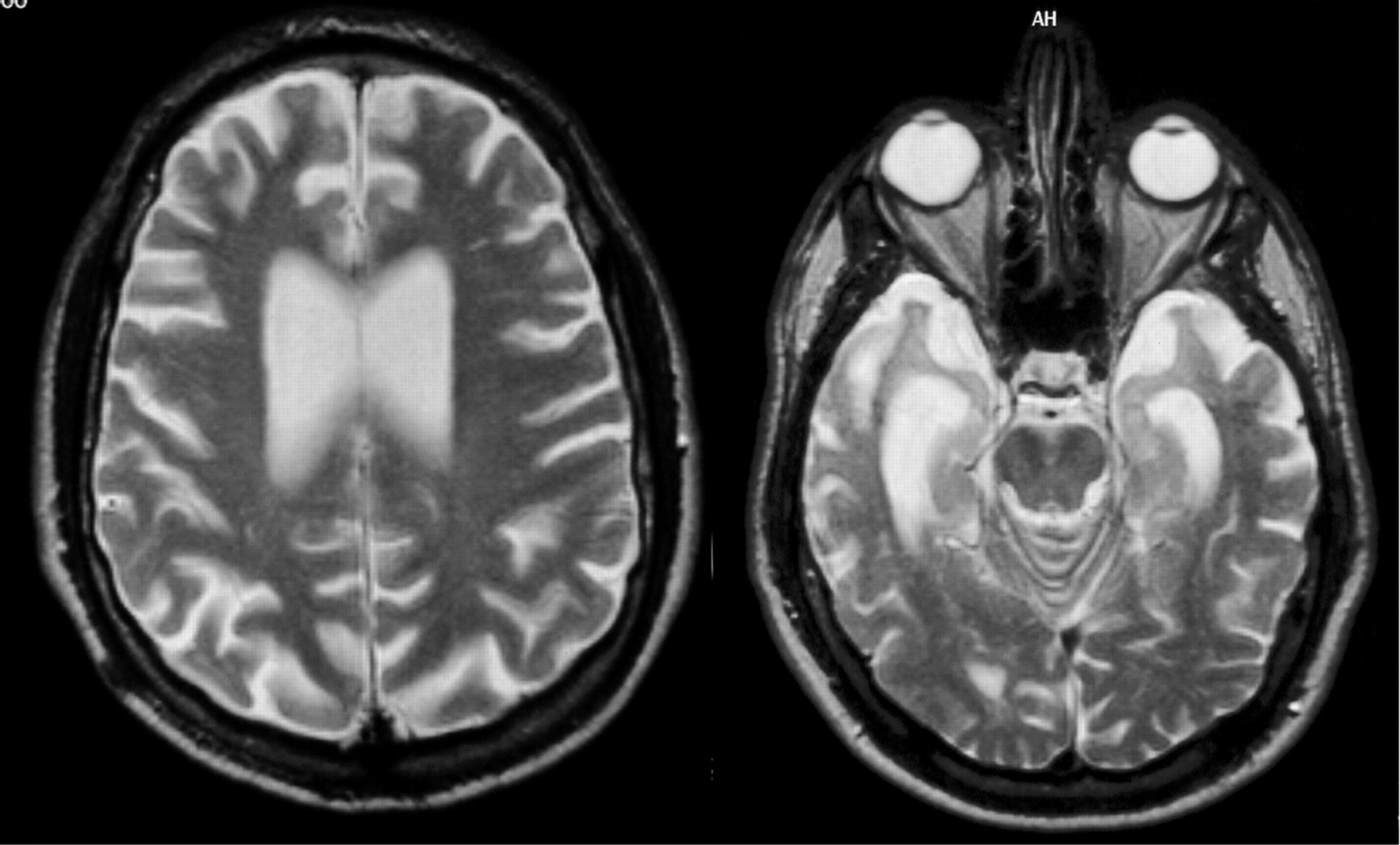

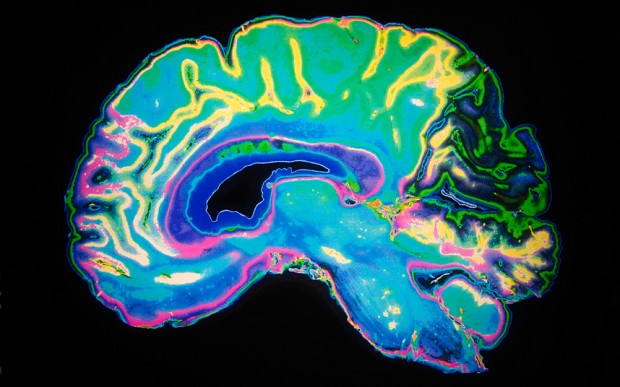

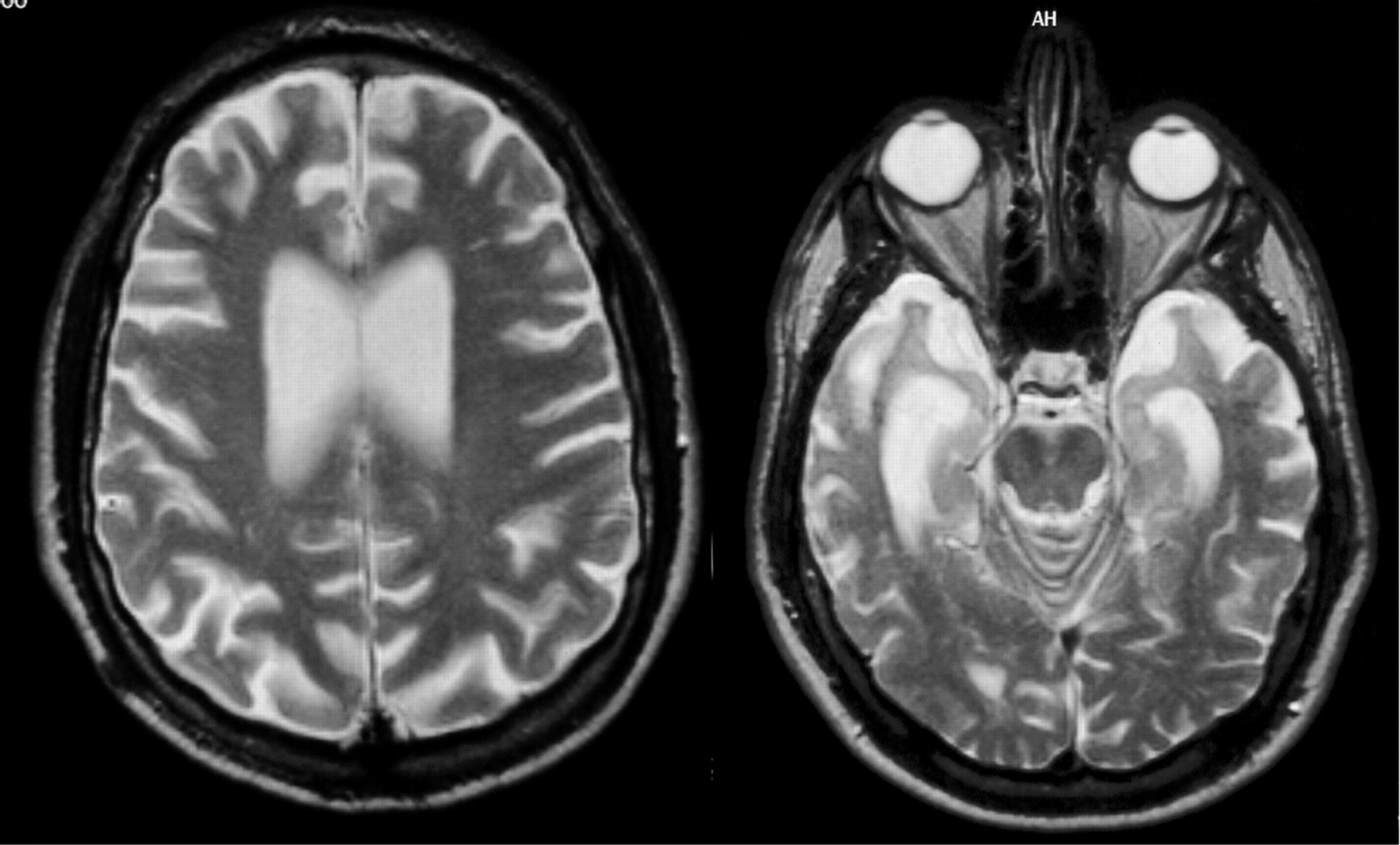

Currently, the definite diagnosis of DAT can only be made through autopsy to find the pathological hallmarks of the disease, microscopic amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. The development of biomarkers that can reliably indicate presence of the disease at the earliest possible stage is therefore an important public health goal. Macroscopically, DAT is associated with progressive brain tissue loss (Braak and Braak, 1998), which MRI can non-invasively visualise to some extent in-vivo (Thompson et al., 2007). Unsurprisingly, MRI has attracted considerable interest as a tool to identify DAT biomarkers.

Histological studies have shown that the hippocampus is particularly vulnerable to DAT pathology and already considerably damaged at the time clinical symptoms first appear (Braak and Braak, 1998).

Spatial cognition

The “cognitive map theory” proposes that the hippocampus of rats and other animals represents their environments, locations within those environments, and their contents, thus providing the basis for spatial memory and flexible navigation. When it comes to humans, the theory suggests a broader function for the hippocampus, based at least in part on lateralisation of function (Burgess, Maguire and O’Keefe, 2002). The cognitive map theory posits that the hippocampus specifically supports allocentric processing of space in contrast to other brain regions, such as the parietal neocortex, which support egocentric processing (O’Keefe and Nadel, 1978).

Structural MRI scans of the brains of humans with extensive navigation experience, licensed London taxi drivers, were analysed and compared with those of control subjects who did not drive taxis. The posterior hippocampi of taxi drivers were significantly larger relative to those of control subjects. A more anterior hippocampal region was larger in control subjects than in taxi drivers. Hippocampal volume correlated with the amount of time spent as a taxi driver (positively in the posterior and negatively in the anterior hippocampus). These data are in accordance with the idea that the posterior hippocampus stores a spatial representation of the environment and can expand regionally to accommodate elaboration of this representation in people with a high dependence on navigational skills. It seems that there is a capacity for local plastic change in the structure of the healthy adult human brain in response to environmental demands.

Wayfinding

Problems in navigation could even be a good way to diagnose early dementia of Alzheimer type (“DAT”), in future. Virtual reality (“VR”) allows naturalistic evaluation of spatial cognition disorders associated with DAT. These measures seem to be well correlated to daily difficulties of people, thus providing specific measures of cognitive deficits and their functional impact. Thus, VR would be a relevant tool for the early screening of dementia and the differential diagnosis of DAT (Déjos et al., 2011).

While there is abundant evidence for spatial learning and memory decrements in patients with unilateral hippocampal lesions, remarkably little research has been done on spatial memory and learning in patients with DAT, in which relatively selective bilateral hippocampal atrophy is consistently reported in the early stages of the disease (de Pol, 2006). Only a few studies have examined static object-location memory tasks in DAT patients, demonstrating impaired performance compared to controls (Bucks and Willison, 1997; Kessels et al., 2010). Using a real-world wayfinding test, Monacelli and colleagues (Monacelli et al., 2003) investigated a group of DAT patients and demonstrated impaired spatial navigation and spatial orientation in the DAT group, possibly due to an underlying deficit in linking landmark information to route knowledge. Similar findings have also been reported using virtual maze-learning paradigms in AD patients (Cushman, Stein and Duffy, 2008; Kalova et al., 2005).

Current pedestrian navigation systems predominantly use distance-to-turn information and directional information to enable a user to navigate. However, Cherrier and colleagues (Cherrier, Mendez and Perryman, 2001) showed that dementia patients performed better on recognition of landmarks compared with recognition and recall of spatial layout. Furthermore, relatively few studies have examined the workplaces of staff compared to those that address outcomes for patients and their families. One theme that has been receiving increasing attention over the last few years in the literature about healing environments is wayfinding.

In addition to a complex floor plan, there are other elements that contribute to poor wayfinding and inadequate or conflicting cues such as colours and lighting (Brown, Wright and Brown, 1997). In addition to these elements, clear and understandable wayfinding and maps are fundamental to becoming oriented. However, maps should be oriented so that the top signifies the direction of movement for ease of use (Ulrich et al., 1994). Moreover, the number of signs available has a significant effect on wayfinding along many different measures including travel time, the frequencies of hesitations, the number of times directions were asked, and the reported level of stress. These results suggest that directional signs should be placed at or before every major intersection, at major destinations, and where a single environmental cue or a series of such cues (for instance, a change in flooring material) conveys the message that the individual is moving from one area into another. If there are no key decision points along a route, signs should be placed approximately every 4.6-7.6 m (Ulrich et al., 1994).

Earlier studies reviewed by Day and Calkins (2002) found that much of the orientation work revolved around “signage”, and indentified that personalised and/or unique signage assisted residents in locating desired destinations. Passini and colleagues (Passini et al., 2000) studied newly admitted residents with dementia, and noted that learning new routes was a slow process. Residents who could not identify paths to desired locations exhibited anxiety, confusion, mutism and even panic. They also noted that some residents perceived patterns on the floor as a barrier. They conclude that “capacity of decision-making is reduced to decisions based on immediate and visually accessible information” whether that information was signs, landmarks, or direct visibility of the desired location. They also noted that the typical location of signs is often not seen by residents whose visual field is low to the ground.

Rule, Milke and Dobbs (1991) also found that features such as many similar doorways along corridors, lack of windows to the outside and signage resulted in poorer orientation. McGilton, Rivera and Dawson (2003) conducted a randomised control trial to ascertain the effects of using a locational map and training techniques on the ability of residents to locate distance locations (a dining room on a different floor). While residents in the treatment group showed significant effect within one week of starting the trial, the effect was not sustained three months later.

Driving and DAT

Safe automobile driving requires a driver to perform multiple competing tasks and attend to a host of objects and ongoing events, while simultaneously monitoring traffic with central and peripheral vision to avoid roadway hazards. Impairments of visual acuity and visual fields increase crashes and traffic violations (Burg, 1971). However, drivers with certain neurological conditions may potentially fail to perceive critical roadside targets and dangers even in the absence of a measurable field defect on standard perimetry or diminished visual acuity (Owsley and McGwin, 1999).

DAT affects processing of visual sensory cues and may produce attentional decline and agnosia (for a review, see Hodges, 2011). These deficits can impair drivers’ processing of visual information such as roadway landmarks and traffic signs that provide key information about a driver’s route, upcoming road hazards, and safety regulations. Uc and colleagues (Uc et al., 2005) studied 33 drivers with probable DAT of mild severity and 137 neurologically normal older adults using a battery of visual and cognitive tests and were asked to report detection of specific landmarks and traffic signs along a segment of an experimental drive. The drivers with mild DAT identified significantly fewer landmarks and traffic signs and made more at-fault safety errors during the task than control subjects.

“The social animal”

“The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement” is a highly celebrated non-fiction book by American journalist David Brooks (Brooks, 2012), who is otherwise best known for his career with The New York Times. The book discusses what drives individual behaviour and decision-making. Brooks asserts that people’s subconscious minds largely determine who they are and how they behave. He argues that deep internal emotions, the “mental sensations that happen to us”, establish the outward mindset that makes decisions such as career choices. Brooks describes the human brain as dependent on what he calls “scouts” running through a deeply complex neuronal network.

Ultimately, Brooks depicts human beings as driven by the universal feelings of loneliness and the need to belong—what he labels “the urge to merge.” He describes people going through “the loneliness loop” of internal isolation, engagement, and then isolation again. He states that people feel the continual need to be understood by others.

We are, above all, “social animals”, and this is of fundamental importance for wellbeing. For example, Prof. Mario Mendez and Prof. Facundo Manes write recently (Mendez and Manes, 2011), and the authors reviewing this important recent collection of papers on social cognition discuss social cognition dysfunction in a number of different clinical situations, and their potential to give rise to problems in social interactions, immoral or even corrupt behaviour.

Response to stress and resilience

“Resilience” refers to a person’s ability to adapt successfully to acute stress, trauma or more chronic forms of adversity. A resilient individual has thus been tested by adversity (Rutter, 2006) and continues to demonstrate adaptive psychological and physiological stress responses, or `psychobiological allostasis’ (McEwen, 2003; Charney, 2004).

The study of resilience, or stress-resistance, originated in the 1970s with a group of researchers who directed their attention to the investigation of children capable of progressing through normal development despite exposure to significant adversity (Masten, 2001). For many years, research focused on identifying the psychosocial determinants of stress resistance, such as positive emotions, the capacity for self-regulation, social competence with peers and a close bond with a primary caregiver, among other factors (Masten, 1998; Rutter, 1985).

The importance of resilience in policy in living well in dementia, and will be considered further in the final chapter, chapter 18.

Contextual learning

Context-dependence effects are pervasive in everyday cognition. When we perceive objects and colours, we always perceive these among other objects and colours. We listen and speak within other word streams, and every atom of meaning emerges from a background of meanings. Acting appropriately in social interactions requires the interpretation of explicit and implicit contextual clues that orient our responses toward being polite, to make a joke or point out an irony, to say or not say something. Cognitive science and neuroscience research have evidenced context-dependence effects in similar domains of visual perception, emotion, language, and social cognition in both normal and neuropsychiatric conditions.

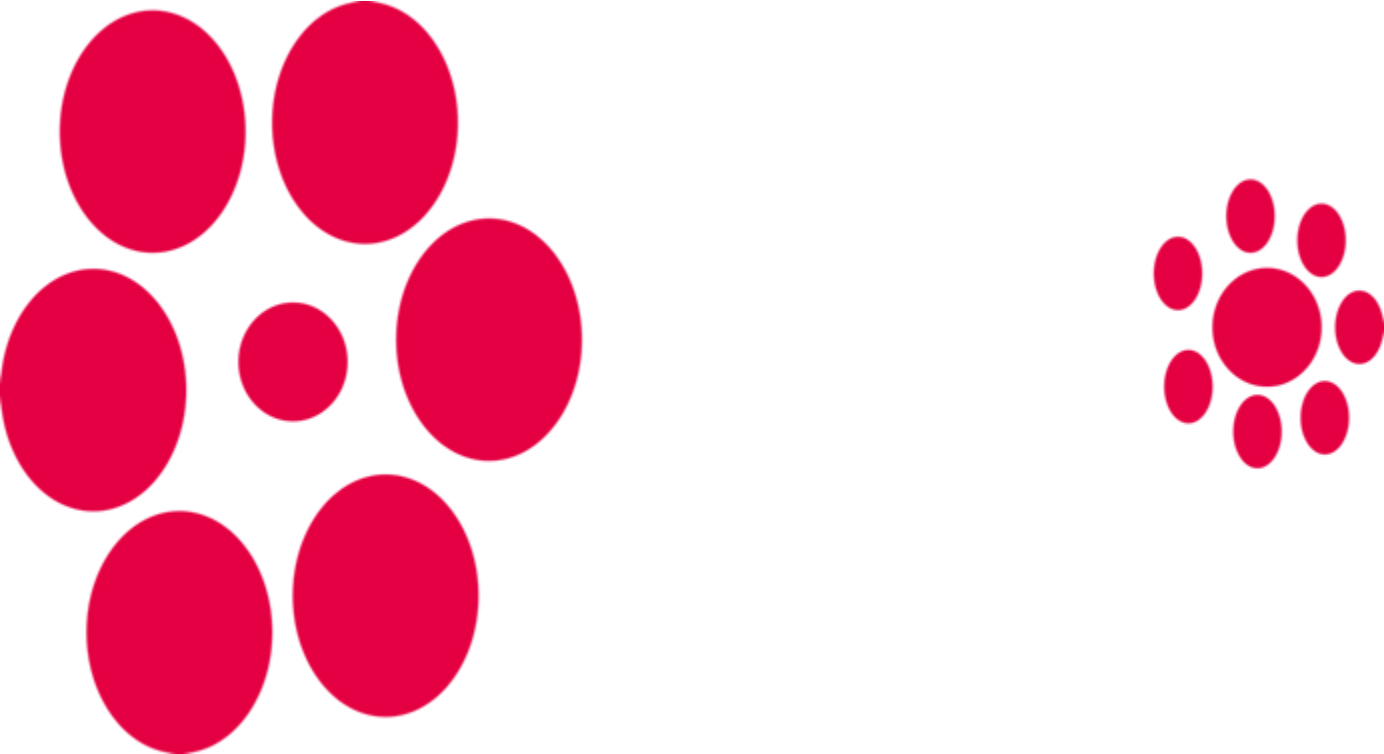

Context is important, as shown by the Ebbinghaus illusion which depicts two identical central circles, surrounded by rings of circles. Despite the fact that they are the same size, one circle is perceived as small and the other as big. The contextual information available (the surrounding circles) creates the perception that the center circles are different sizes. This is shown below.

Contextual effects are present at every level, from basic perception to social interaction. This means that we do not perceive objects or process cognitive events in an abstract and universal way. The specific significance of an object, emotion, word, or social situation depends on the contextual effects. During normal cognition, our brains do not process targets and contexts separately; rather, targets are in context.

Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and the social context

The “behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia“ (bvFTD) is characterised by insidiously progressive changes in personality and social interaction that typically precede other cognitive deficits. Patients may present with compulsiveness, perseverations, or stereotyped repetitive acts, loss of self-consciousness, diminished interest for activities or hobbies, or withdrawal and apathy. Increased appetite with a tendency for sweet foods is common, and hypersexuality and hyperorality may develop, especially in the advanced stages of the disease.

Early diagnosis is difficult because behavioural problems, invariably reported by friends or family, dominate the clinical picture while cognitive functions are still relatively intact. This is why it is so important to appreciate that dementia does not equal memory problems in every single case (and this is discussed in chapter 18). People with bvFTD often score normally on the Mini-Mental State Examination (“MMSE”), and conventional structural brain imaging (CT and MRI) may not be sensitive to the early changes associated with bvFTD at all. Therefore, early diagnosis relies on clinical interviews and caregiver reports; it can be considerably difficult to distinguish bvFTD from primary psychiatric syndromes.

Patients with bvFTD are now reported consistently to demonstrate reliably deficits in several domains of social cognition such as recognising emotions in facial expressions, empathy processing, decision-making, figurative language, theory of mind, and interpersonal norms. Little was known about the brains of such patients from an neuroimaging perspective. In particular, given the nature of the cognitive deficits demonstrated by these patients, the authors postulated that, relatively early in the course of the disease, the ventromedial (VMPFC) (or orbitofrontal) cortex is a major locus of dysfunction and that this may relate to the behavioural presentation of these patients clinically described in the individual case histories. A greater definition of the rôle of the ventral frontal cortex, especially given findings in the animal literature, in reversal learning and decision has been a highly influential tranche of research subsequently (Clark, Cools and Robbins, 2004).

At approximately the same time, Lough, Gregory and Hodges (2001) demonstrated relatively intact general neuropsychological and executive function, but extremely poor performance on tasks of theory of mind (ToM). This indicates a dissociation of social cognition and executive function suggesting that in psychiatric presentations of bv-FTD there may be a fundamental deficit in theory of mind independent of the level of executive function. The implications of this finding for diagnostic procedures and possible behavioural management are discussed.

Liu and colleagues (Liu et al., 2004) later compared the behavioral features and to investigate the neuroanatomical correlates of behavioral dysfunction in anatomically defined temporal and behavioural variants of frontotemporal dementia (tvFTD and bvFTD). Volumetric measurements of the frontal, anterior temporal, ventromedial frontal cortical (VMFC), and amygdala regions were made in 51 patients with FTD and 20 normal control subjects, as well as 22 patients with dementia of Alzheimer type (DAT) who were used as dementia controls. FTD patients were classified as bvFTD or tvFTD based on the relative degree of frontal and anterior temporal volume loss compared with controls. Behavioural symptoms, cerebral volumes, and the relationship between them were examined across groups. Both variants of FTD showed significant increases in rates of elation, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior compared with DAT. The bvFTD group also showed more anxiety, apathy, and eating disorders, and tvFTD showed a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances than DAT. The only behaviours that differed significantly between bvFTD and tvFTD were apathy, greater in bvFTD, and sleep disorders, more frequent in tvFTD. BvFTD was associated with greater frontal atrophy and tvFTD was associated with more temporal and amygdala atrophy compared with AD, but both groups showed significant atrophy in the VMFC compared with DAT, which was not associated with VMFC atrophy. In FTD, the presence of many of the behavioral disorders was associated with decreased volume in right-hemispheric regions.

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), tensor-based morphometry (TBM), Lu et al. (Lu et al., 2013) was finally used to determine distinct patterns of atrophy between these three clinical groups. The authors concluded that The bvFTD, SV-PPA, and NF-PPA groups displayed distinct patterns of progressive atrophy over a one-year period that correspond well to the behavioral disturbances characteristic of the clinical syndromes. More specifically, the bvFTD group showed significant white matter contraction and presence of behavioral symptoms at baseline predicted significant volume loss of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. These areas of structural atrophy seem also to be correlated to functional deficits in the case of bvFTD, and now seem to suggest a dissociation in dysfunction even between reversal learning and decision learning deficits at a finer level.

Finally, to complete things, Bertoux and colleagues (Bertoux et al., 2012b) reported that gray matter volume within BA 9 in the medial prefrontal was correlated with scores on the emotion recognition subtest of the he social cognition and emotional assessment”, and the severity of apathetic symptoms in the apathy scale covaried with gray matter volume in the lateral prefrontal cortex (BA 44/45).

The “social context network model”

At a phenomenological level, context-based predictions make social cognition more efficient. Prototypical situations in the environment are represented in “context frames” that integrate information about the meanings of social targets (e.g., an emotional face, a speech) that are likely to appear in a specific scene with information about their relationships.

Ibañez and Manes (2012) proposed that there exists a cortical network that mediates the processing of such contextual associations. This social context network involves regions of the frontal, insular, and temporal cortices. They postulate that frontal areas (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex, lateral prefrontal cortex, superior orbital sulcus) update and associate ongoing contextual information in relation to episodic memory and target-context associations. The temporal regions (amygdala, hippocampus, perirhinal and para-hippocampal cortices) index the value learning of target-context associations. Finally, the insular cortex coordinates internal and external milieus in an internal motivational state. In this way, the insula would provide information integration from internal states and social contexts to produce a global feeling state.

The initial symptoms of FTD reflect the involvement of orbitofrontal cortex as well as the disruption of the rostral limbic system including the insula, the anterior cingulate cortex, the striatum, the amygdala, and the medial frontal lobes. This system is involved in a number of processes such as the evaluation of the motivational or emotional content of internal and external stimuli, error detection, response selection and decision-making, and subsequent regulation of context-dependent behaviours. Recent neuroimaging studies suggest that patients with FTD show predominantly right frontal, anterior insular, and anterior cingulate deterioration, with pronounced orbitofrontal cortex atrophy. Additionally, some studies have reported correlations between behavioural symptoms and brain structures, suggesting that the right orbitofrontal cortex regulates behavior together with a predominantly right-side network involving the insula and striatum. In addition, voxel-based morphometry studies have shown that patients with bvFTD have significant gray matter loss in the anterior insula and in a variety of prefrontal areas.

REFERENCES

Bertoux, M., Volle, E., Funkiewiez, A., de Souza, L.C,, Leclercq, D., and Dubois, B. (2012b) Social Cognition and Emotional Assessment (SEA) is a marker of medial and orbital frontal functions: a voxel-based morphometry study in behavioral variant of frontotemporal degeneration. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 18(6), pp. 972-85.

Braak H, and Braak E. (1998) Evolution of neuronal changes in the course of Alzheimer’s disease, J Neural Transm Suppl, 53, pp. 127–40.

Brooks, D. (2012) The Social Animal: The Hidden Sources of Love, Character, and Achievement. London: Random House Trade.

Brown, B., Wright, H., and Brown, C. (1997) A post-occupancy evaluation of wayfinding in

a pediatric hospital: research findings and implications for instruction,

J Architect Plan Res, 14(1):35e51.

Bucks, R.S., and Willison, J.R. (1997) Development and validation of the Location Learning Test (LLT): a test of visuo-spatial learning designed for use with older

adults and dementia, Clin Neuropsychol, 11, pp. 273–286.

Burg, A. (1971) Vision and driving: a report on research, Hum Factors, 13, pp. 79–87.

Burgess, N., Maguire, E.A., and O’Keefe, J. (2002) The Human Hippocampus and Review Spatial and Episodic Memory, Neuron, 35, pp. 625–641.

Charney, D.S. (2004) Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress, Am. J. Psychiatry, 161, pp. 195–216.

Clark, L., Cools, R., and Robbins, T.W. (2004) The neuropsychology of the ventral prefrontal cortex: decision-making and reversal learning, Brain and Cognition, 55, 41-53.

Cherrier, M., Mendez, M., and Perryman, K. (2001) Route Learning Performance in Alzheimer Disease Patients, Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology, 14:3, pp. 159– 168.

Cushman, L.A., Stein, K., and Duffy C.J. (2008) Detecting navigational deficits in cognitive aging and Alzheimer disease using virtual reality, Neurology, 71, pp. 888–895.

Day, K and Calkins, MP. (2002) Design and Dementia, in: Churchman, R.B.A. (ed.) Handbook of Environmental Psychology, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

de Pol, L.A., van der Flier, W.M., Korf, E.S., Fox, N.C., Barkhof, F., and Scheltens, P. (2007) Baseline predictors of rates of hippocampal atrophy in mild cognitive impairment, Neurology, 69, pp. 1491–7.

Déjos, M., Sauzéon, H., Falière, A., and N’Kaoua, B. (2011) Naturalistic assessment of spatial cognition disorders in Alzheimer’s disease using virtual reality: Abstracts [CO37-005–EN], Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 54S, e87–e94 (p. e90).

Ferri, C.P., Prince, M., Brayne C, Brodaty, H., Fratiglioni, L., Ganguli, M., Hall, K., Hasegawa, K., Hendrie, H., Huang, Y., Jorm, A., Mathers, C., Menezes, P.R., Rimmer, E., and Scazufca, M; Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2005) Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study, Lancet, 366, pp. 2112–7.

Hodges, J.R. (2010) Chapter 24.2.2 Dementia, in London, in Warrell, D.A., Cox, T.M., and Firth, J.D. (eds.) Oxford Textbook of Medicine, Oxford, UK (5th edition): Oxford University Press.

Ibañez, A. and Manes, F. (2012) Views and reviews: Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, Neurology, 78, pp. 1354–1362.

Kalová, E., Vlcek, K., Jarolímová, E., and Bures, J. (2005) Allothetic orientation and sequential ordering of places is impaired in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: corresponding results in real space tests and computer tests, Behav Brain Res, 159: 175–186.

Kessels, R.P.C., Rijken, S., Joosten-Weyn Banningh, L.W.A., Van Es, N., and Olde Rikkert, M.G.M. (2010) Categorical spatial memory in patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer dementia: positional versus object-location recall, J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 16, pp. 200–204.

Liu, W., Miller, B.L., Kramer, J.H., Rankin, K., Wyss-Coray, C., Gearhart, R., Phengrasamy, L., Weiner, M., and Rosen, H.J. (2004) Behavioral disorders in the frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia, Neurology, 62(5), pp. 742-8.

Lough, S., Gregory, C., and Hodges, J.R. (2001) Dissociation of social cognition and executive function in frontal variant frontotemporal dementia, Neurocase, 7(2), pp. 123-30.

Lu, P.H., Mendez, M.F., Lee, G.J., Leow, A.D., Lee, H.W., Shapira, J., Jimenez, E., Boeve, B.B., Caselli, R.J., Graff-Radford, N.R., Jack, C.R., Kramer, J.H., Miller, B.L., Bartzokis, G., Thompson, P.M., and Knopman, D.S. (2013) Patterns of brain atrophy in clinical variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 35(1-2): pp. 34-50.

Maguire, E.A., Gadian, D.G., Joshnsrude, I.S., Good, C.D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R.S.J., and Frith, C.D. (2000) Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers, Procl Acad Nat Sci, 97(8), pp. 4398-403.

Masten, A.S. (2001) Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol, 56, pp. 227–238.

Masten, A.S., and Coatsworth, J.D. (1998) The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. Lessons from research on successful children, Am Psychol, 53, pp. 205–220.

McEwen, B.S. (2003) Mood disorders and allostatic load, Biol Psychiatry, 54, pp. 200–207.

McGilton, K.S., Rivera, T.M., and Dawson,, R. (2003) Can we help persons with dementia find their way in a new environment?, Aging and Mental Health, 7, pp. 363-71.

Mendez, M.F., Manes, F. (2011) The emerging impact of social neuroscience on neuropsychiatry and clinical neuroscience, Soc Neurosci, 6(5-6), pp. 415-9.

Monacelli, A.M., Cushman, L.A., Kavcic, V., and Duffy C.J. (2003) Spatial disorientation in Alzheimer’s disease: the remembrance of things passed, Neurology, 61, pp. 1491–1497.

O’Keefe, J., and Nadel, L. (1978) The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Owsley, C., and McGwin, G. (1999) Vision impairment and driving, Surv Ophthalmol, 43, pp. 535–50.

Passini, R., Pigot, H., Rainville, C., Tétreault, M.H. (2000) Wayfinding in a Nursing Home for Advanced Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type, Environment & Behavior, 32, pp. 684–710.

Rule, B.G., Milke, D.L., Dobbs, A.R. (1992) Design of institutions: Cognitive functioning and social interactions of the aged resident, Journal of Applied Gerontology, 11, pp. 475–488.

Rutter, M. (1985) Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder, Br J Psychiatry, 147, pp. 598–611.

Rutter, M. (2006) Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding, Ann NY Acad Sci, 1094, pp. 1–12.

Thompson, P.M., Hayashi, K.M., Dutton, R.A., Chiang, M.C., Leow, A.D., Sowell, E.R., De Uc, E.Y., Rizzo, M., Anderson, S.W., Shi, Q., and Dawson, J.D. (2005) Driver landmark and traffic sign identification in early Alzheimer’s disease, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 76, pp. 764–768.

Ulrich, R.S., Quan, X., Zimring, C., Joseph, A., and Choudhary, R. (2004) The role of the physical

environment in the hospital of 21st century: a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Concord: CA: Center for Health Design.

van de Pol, L.A., Hensel, A., van der Flier, W.M., Visser, P.J., Pijnenburg, Y.A., Barkhof, F., Gertz, H.J., and Scheltens, P. (2006) Hippocampal atrophy on MRI in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 77, pp. 439–442.

Zubicaray, G., Becker, J.T., Lopez, O.L., Aizenstein, H.J., and Toga A.W. (2007) Tracking Alzheimer’s Disease, Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1097, pp. 183-214. [Review.]