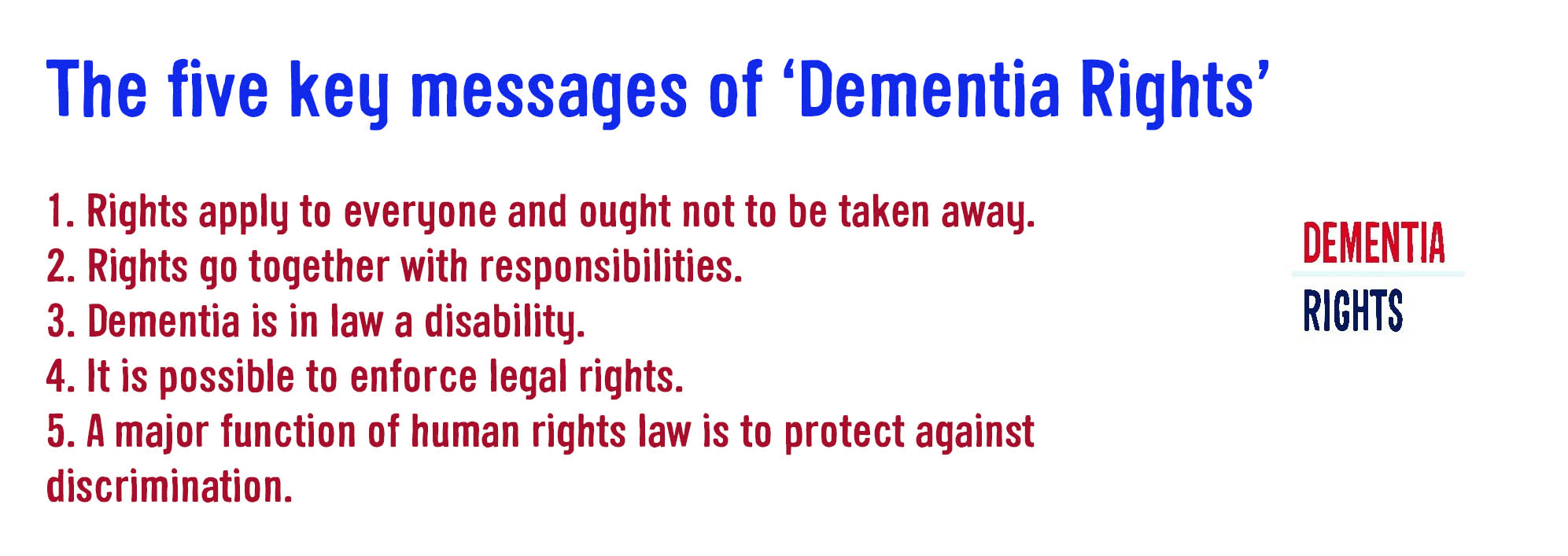

Ideally, at the end of a ‘Dementia Friends’ session, each participant will have learned the five key things that everyone should know about dementia, and aspired to turn an understanding into a commitment to action.

In this blogpost , I wish just to discuss a little bit these messages in a way that is interesting. If you’re interested in finding out more about ‘Dementia Friends’, please go to their website. Whatever, I hope you become interested about the dementias, even if you are not already.

I am a “Dementia Friends Champion”.

1. Dementia is not a natural part of aging.

This is an extremely important message.

However, it is known that the greatest known risk factor for dementias overall is increasing age. The majority of people with Alzheimer’s disease, typically manifest as problems in new learning and short term memory are indeed 65 and older.

But Alzheimer’s disease is not just a disease of old age. Up to 5 percent of people with the disease have early onset Alzheimer’s (also known as younger-onset), which often appears when someone is in their 40s or 50s.

When you see someone who is old, say above 65, they do not necessarily have dementia.

Dementia, caused by a disease of the brain, can affect any of the functions of the brain – such as movement, visual perception, memory or attention.

It’s felt that almost 40 percent of people over the age of 65 experience some form of memory loss.

When there is no underlying medical condition causing this memory loss, it is known as “age-associated memory impairment,” which is considered a part of the normal aging process.

But brain diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are completely different.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia worldwide.

The risk of getting dementia increases with age, but it is important to remember that the majority of older people do not get dementia. It is not a normal part of ageing.

Old age does not cause dementia but is a factor in developing the condition. The probability of an individual developing dementia increases with age, but not everyone will develop dementia in old age.

Dementia can happen to anybody, but it is more common after the age of 65 years.

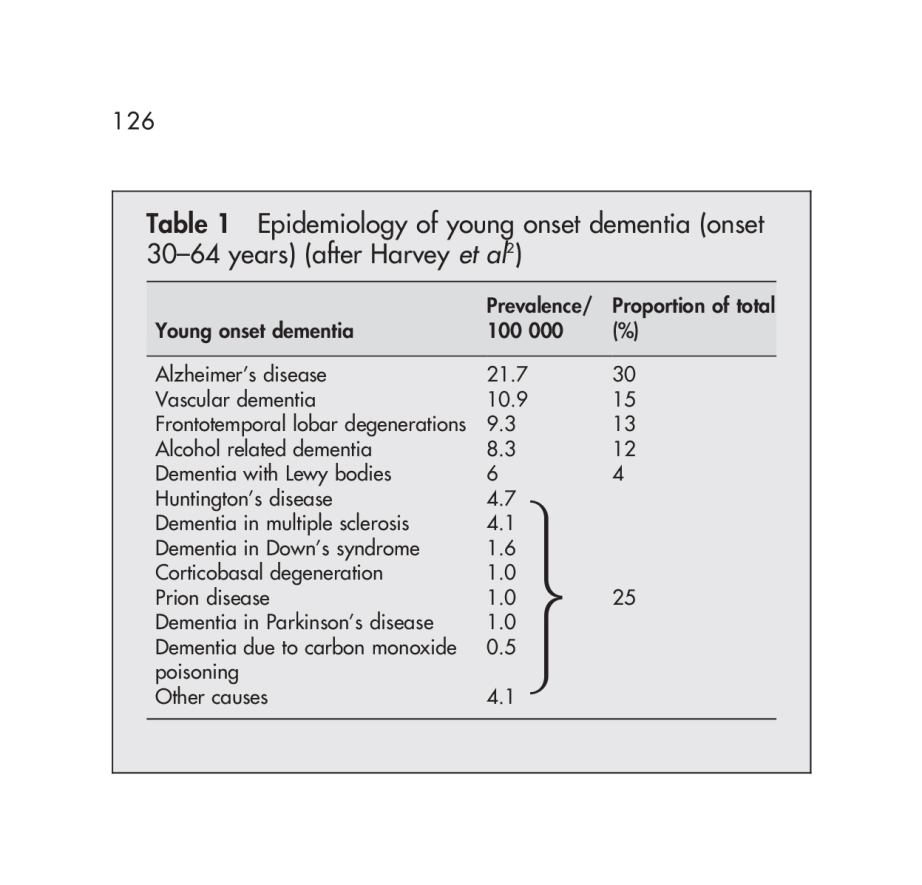

Indeed, “young onset dementia” (YOD) plays out at a much younger age, anyway.

YOD, which most often plays itself out in the form of Alzheimer’s disease, is an abnormal neurological condition that is likely caused by a combination of factors.

YOD is increasingly recognised as an important clinical and social issue. This group of individuals have distinct needs for living well with dementia as far as possible.

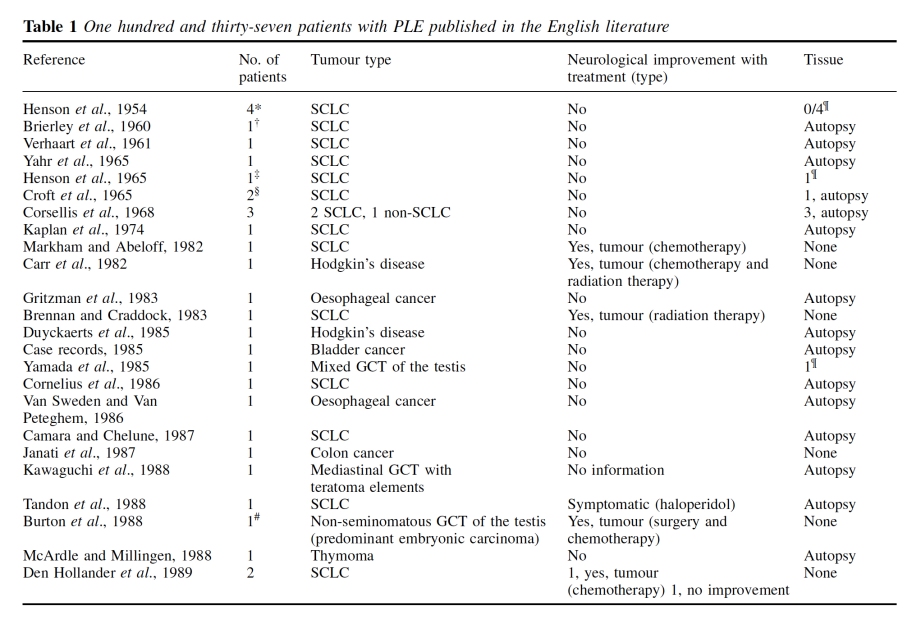

Young onset dementia (by EL Sampson, JD Warren and MN Rossor) [Postgrad Med J 2004;80:125–139. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.011171] cite a useful breakdown of the most common causes.

These causes are diseases, and produce a chronic, progressive course of dementia. The spectrum of diseases causes YOD bears some similarities and differences to that of diseases causing dementia in the older age group.

(from Sampson, Warren and Rossor, 2004)

Prevalence rates of young onset dementia have been estimated between 67 to 81 per 100 000 in the 45 to 65 year old age group.

A rare type of dementia, the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) was first reported in 1996; the youngest patient developed symptoms at 16 years of age (reviewed in Verity et al., 2000).

As described in the WHO factsheet 180, Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is a rare and fatal human neurodegenerative condition which is classified as a Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE), because of its ability to be transmitted and the characteristic spongy degeneration of the brain that it causes.

Its diagnosis does need to be in very specialist hands.

But, notwithstanding all that, is likely that the situation is likely to be very complicated.

The basal forebrain cholinergic complex including nucleus basalis of Meynert provides the mayor cholinergic projections to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.

Source here.

It’s thought that the hippocampus represents the story of facts or events (episodic memory), one of the bookcases in the “bookcase analogy” of the Dementia Friends initiative.

But it has latterly been acknowledged (Schliebs and Arendt, 2011) that he cholinergic neurones of this complex have been described to undergo moderate degenerative changes during aging, resulting in cholinergic hypo function that has been related to the progressing memory deficits with ageing.

2. It is caused by diseases of the brain.

Prof John Hodges, who did the Foreword to my book, has written the current chapter on dementia in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine. He also supervised my Ph.D. The chapter is here.

There is a huge number of causes of dementia.

The ‘qualifier’ on this statement is that the diseases affect the brain somehow to produce the problems in thinking. But dementia can occur in the context of conditions which affect the rest of the body too, such as syphilis or systematic lupus erythematosus (“SLE”).

That ‘Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain’ may seem like a pretty innocuous statement.

There have been numerous attempts at looking at the numbers of the different causes of dementia, varying in overall success over the years.

One study “Prevalence of dementia subtypes: A 30-year retrospective survey of neuropathological reports” came from Hans Brunnström, Lars Gustafson, Ulla Passant and Elisabet Englundemail in 2008.

The authors investigated the distribution of neuropathologically defined dementia subtypes among individuals with dementia disorder.

The neuropathological reports were studied on all patients (n = 524; 55.3% females; median age 80, range 39–102 years) with clinically diagnosed dementia disorder who underwent complete post mortem examination including neuropathological examination within the Department of Pathology at the University Hospital in Lund, Sweden, during the years 1974–2004.

The neuropathological diagnosis was Alzheimer’s disease in 42.0% of the cases, vascular dementia in 23.7%, dementia of combined Alzheimer and vascular pathology in 21.6%, and frontotemporal dementia in 4.0% of the patients.

Different types of dementia (and factsheets about them) are summarised in this page from the Alzheimer’s Society.

Part of the problems with the statement comes from the definition of ‘dementia’.

For example, a WHO definition is provided thus:

“Dementia is a syndrome – usually of a chronic or progressive nature – in which there is deterioration in cognitive function (i.e. the ability to process thought) beyond what might be expected from normal ageing. It affects memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language, and judgement. Consciousness is not affected. The impairment in cognitive function is commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour, or motivation.”

However academics and practitioners over the years have squabbled over the nuances of the definition. Should the definition compulsorily include memory in the early stages? Most people I think would agree ‘no’, if only because of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia where individuals present with an insidious progressive change in behaviour and personality in the early stages can report no changes in their memory. And can it be reversible?

But problems in metabolism from the rest of the body can cause problems in brain function. The list is a long one, and an introduction to this topic here.

And antibodies raised in cancers which haven’t revealed themselves yet can cause a dementia-like picture.

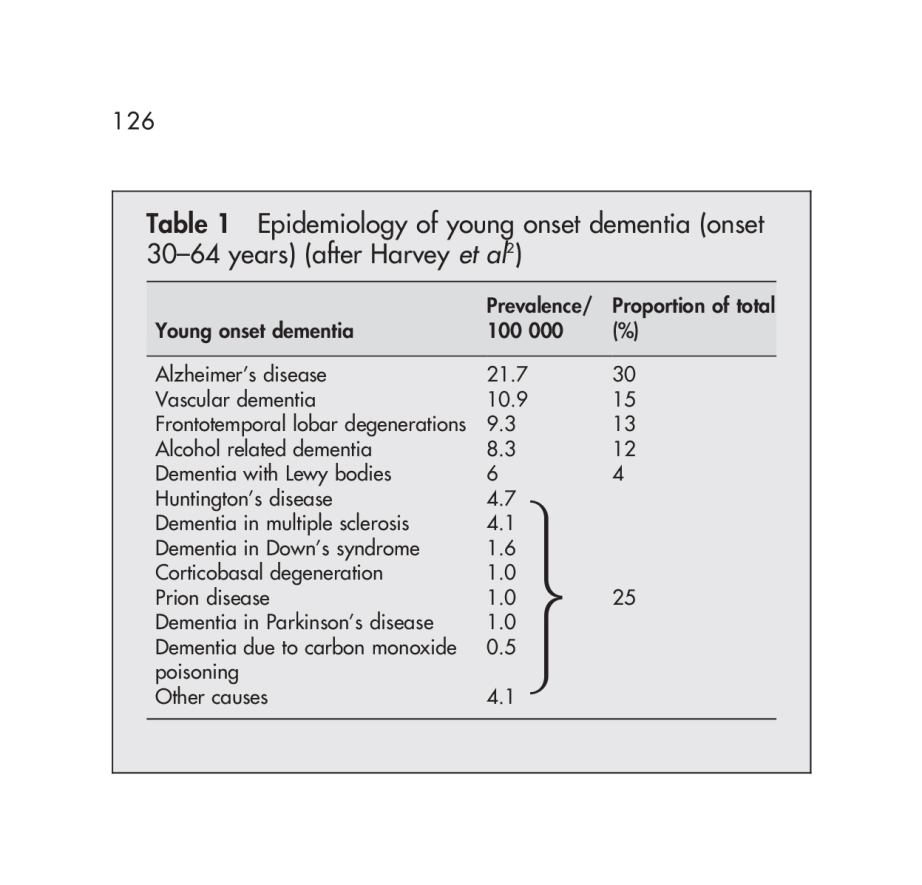

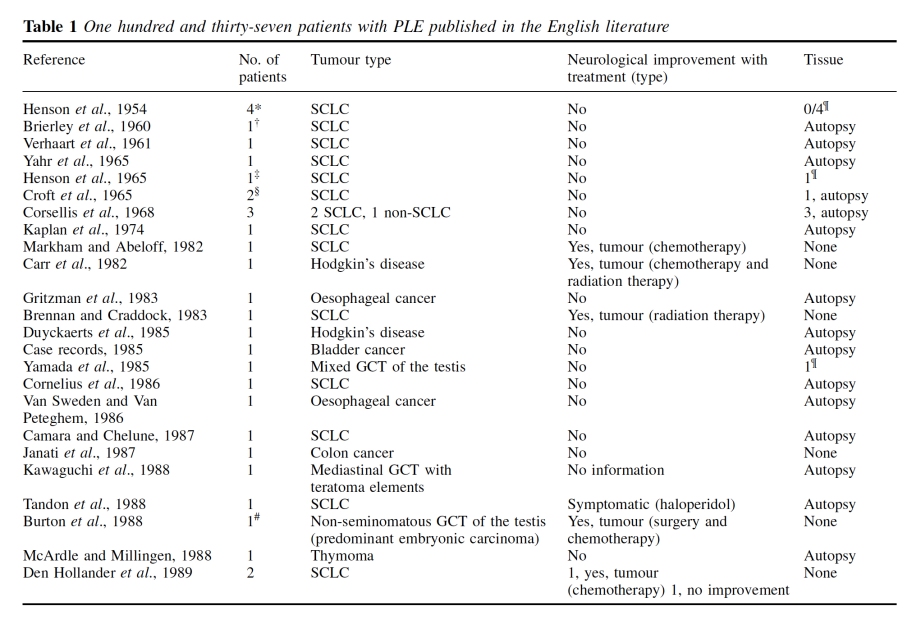

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) is a rare disorder characterized by personality changes, irritability, depression, seizures, memory loss and sometimes dementia.

This diagnosis is difficult because clinical markers are often lacking, and symptoms usually precede the diagnosis of cancer or mimic other complications.

A range of tumours outside of the brain can be implicated in this complicated conditions, including oesophagus, lung, bladder, colon, lung, thymus and breast.

This is for example a helpful summary table from Gultekin and colleagues in Brain. 2000 Jul;123 ( Pt 7):1481-94.

They can be associated with markers in the fluid surrounding the spinal cord, and in magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. But to call them “diseases of the brain” would be a massive over-simplification?

And there might not be a biological disease at all causing profound symptoms.

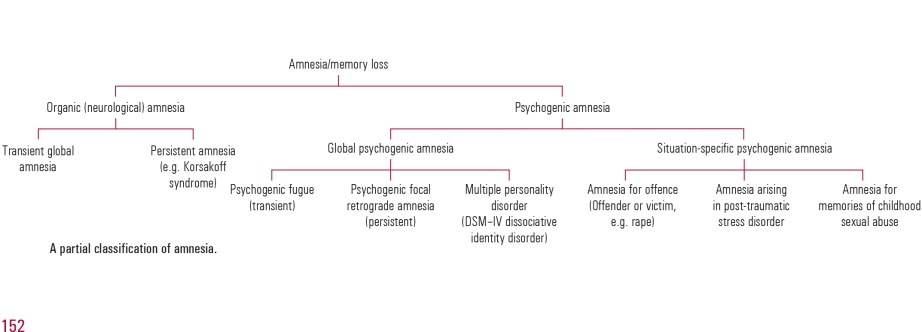

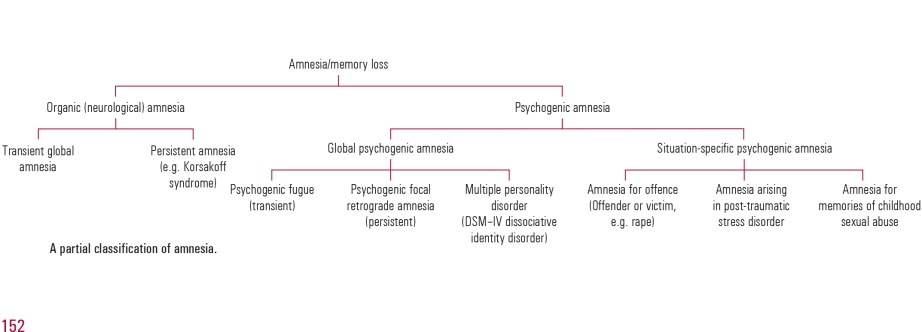

McKay and Kopelman’s article “Psychogenic amnesia: when memory complaints are medically unexplained” in Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009) [vol. 15, 152–158 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.105.001586] is an extremely useful introduction.

Amnesia is a particular cognitive problem. Amnesia has been defined as ‘an abnormal mental state in which memory and learning are affected out of all proportion to other cognitive functions in an otherwise alert and responsive patient’ (Victor 1971).

According to them, “A number of terms have been used to describe medically unexplained amnesia, including ‘hysterical’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘dissociative’ and ‘functional’. Each requires the exclusion of an underlying neurological cause and the identification of a precipitating stress that has resulted in amnesia. Unfortunately, the presence of amnesia may make it difficult to identify the stress until either informants have come forward or the amnesia itself has resolved”.

They helpfully provide this scheme for looking at the causes.

Hans J. Markowitsch looked at “Psychogenic amnesia” in an extremely useful article in NeuroImage 20 (2003) S132–S138.

Markowitsch, a world leader in memory, kicked off with the realisation that sometimes a disease of the brain, in terms of an identifiable pathology, often could not be located for quite profound symptoms.

“Commonly, memory disturbances are related to organic brain damage. Nevertheless, especially the old psychiatric literature provides numerous examples of patients with selective amnesia due to what at that time was preferentially named hysteria and which implied that both environmental circumstances and personality traits influence bodily and brain states to a considerable degree. Awareness of the existence of relations between cognition, soma, and psyche has increased especially in recent times

and has created the research branch named cognitive neuropsychiatry.”

Mizutani and colleagues (2014) have indeed reported a case which could to all intents-and-purposes have been caused by a disease of the brain.

Its cause is an overactive thyroid, a gland in the neck.

“We report the case of a 20-year-old Japanese woman with no psychiatric history with apparent dissociativesymptoms. These consisted of amnesia for episodes of shoplifting behaviors and a suicide attempt, developing together with an exacerbation of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Patients with Graves’ disease frequently manifest various psychiatric disorders; however, very few reports have described dissociative disorder due to this disease. Along with other possible causes, for example, encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, clinicians should be aware of this possibility.”

Dissociative disorders can take many forms – see this factsheet from Mind.

It is thought that dissociative amnesia is amnesia caused by trauma or stress, resulting in an inability to recall important personal information.

Therefore ‘Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain’ is not in fact an innocuous statement. But for the purposes of “Dementia Friends”, it is.

3. It’s not just about memory loss.

This statement is perhaps ambiguous.

“Not just” might be taken to imply that memory loss should be a part of the presenting symptoms of the dementia.

On the other hand, it might be taken to mean “the presentation can have nothing to do with memory loss”, which is an accurate statement given the current state of play.

John (Hodges) comments:

“The definition of dementia has evolved from one of progressive global intellectual deterioration to a syndrome consisting of progressive impairment in memory and at least one other cognitive deficit (aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbance in executive function) in the absence of another explanatory central nervous system disorder, depression, or delirium (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 4th edition (DSM-IV)). Even this recent syndrome concept is becoming inadequate, as researchers and clinicians become more aware of the specific early cognitive profile associated with different dementia syndromes.”

I remember, as part of my own Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge on the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia,virtually all the persons with that specific dementia syndrome, in my study later published in the prestigious journal Brain, had plum-normal memory. In the most up to date global criteria for this syndrome, which should be in the hands of experts, memory is not even part of the six discriminating features of this syndrome as reported.

Exactly the same arguments hold for dementia syndromes which might be picked up through a subtle but robust problem with visual perception (e.g.posterior cortical atrophy) or in language (e.g. semantic dementia or progressive (non-) fluent aphasia, logopenic aphasia.) <- note that this is in the absence of a profound amnestic syndrome (substantial memory problems) as us cognitive neuropsychologists would put it.

Dementia is a general term for a number of progressive diseases affecting over 800,000 people living in the UK, it is estimated.

The heart pumps blood around the circulation.

The liver is involved in making things and breaking down things in metabolism.

The functions of the brain are wide ranging.

There are about 100 billion nerve cells called neurones in the brain. Some of the connections between them indeed do nothing. It has been a conundrum of modern neuroscience to work out why so much intense connectivity is devoted to the brain in humans, compared to other animals.

For example, there’s a part of the brain involved in vision, near the back of the head, known as the ‘occipital cortex’. Horace Barlow, now Professor Emeritus in physiology at the University of Cambridge, who indeed supervised Prof Colin Blakemore, Professor Emeritus in physiology at the University of Oxford, in fact asked the very question which exemplifies one of the major problems with understanding our brain.

That is, why does the brain devote so many neurones in the occipital cortex to vision, when the functions such as colour and movement tracking are indeed in the eye of a fly.

The answer Barlow felt, and subsequently agreed to by many eminent people around the world, is that the brain is somehow involved in solving “the binding problem”. For example, when we perceive a bumble bee in front of us, we can somehow combine the colour, movement and shape (for example) of a moving bumble bee, together with it buzzing.

The brain combines these separate attributes into one giant perception, known as ‘gestalt’.

What an individual with dementia notices differently to before, on account of his or her dementia, will depend on the part of the brain which is affected. Indeed, cognitive neurologists are able to identify which part of the brain is likely to be affected from this constellation of symptoms, in much the same way cardiologists can identify the precise defect in the heart from hearing a murmur with a stethoscope.

In a dementia known as ‘posterior cortical atrophy’, the part of the brain involved with higher order visual processing can be affected, leading to real problems in perception. For example, that’s why the well known author has trouble in recognising coins from their shape from touching them in his pocket. This phenomenon is known as ‘agnosia’, meaning literally ‘lack of knowing’.

If a part of the brain which is deeply involved in personality and behaviour, it would not be a big surprise if that function is affected in a dementia which selectively goes for that part of the brain at first. That’s indeed what I showed and published in an international journal in 1999, for behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, one of the young onset dementias.

If the circuits involved in encoding a new memory or learning, or retrieving short term memories are affected, a person living with dementia might have problems with these functions. That’s indeed what happens in the most common type of dementia in the world, the dementia of the Alzheimer Type. This arises in a part of the brain near the ear.

If the part of the brain in a dementia which is implicated in ‘semantic knowledge’, e.g. knowledge for categories such as animals or plants, you might get a semantic dementia. This also arises from a part of the brain near the ear, but slightly lower and slightly more laterally.

So it would therefore be a major mistake to think a person you encounter, with memory problems, must definitely be living with dementia.

And on top of this memory problems can be caused by ageing. It would be wrong to pathologise normal ageing in this way.

Severe memory problems can be caused by depression, particularly in the elderly.

In summary, dementia is not just about losing your memory.

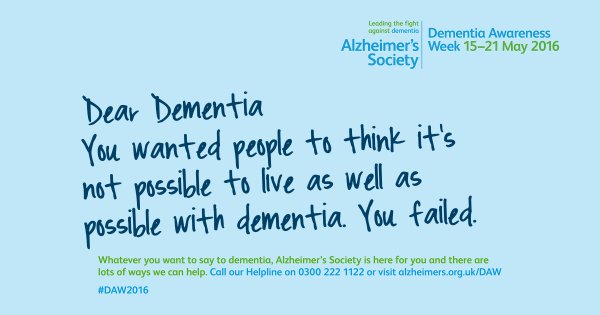

4. It’s possible to live well with dementia.

I of course passionately believe this, or I wouldn’t have written a book on it. It is, apart from all else potentially, the name of the current English dementia strategy.

So why is this “it’s possible to live well with dementia” even a statement in “Dementia Friends“, a Public Health England initiative delivered by the Alzheimer’s Society. It should be obvious shouldn’t it?

The answer comes in the ‘icebreaker’ exercise at the beginning of the Dementia Friends session. Attendees are asked to think of the first word that springs to mind when they think of dementia.

“Suffering”

“Horrible”

“Terrible”

And indeed it would be wrong to ignore how distressing a diagnosis of dementia can be for certain individuals with dementia. Take for example people with diffuse Lewy Body disease, typically individuals in the younger age bracket in their 50s, who have complete insight into the condition, realise that memory might be going, and are exasperated at the ‘night terrors’.

‘Living well with dementia’, conversely, is supposed to counteract the negative word associations may people have about dementia. It’s felt that such negative connotations contribute to the stigma individuals with dementia can experience after their diagnosis. This can ultimately lead to discrimination, hence the need for communities which are welcoming to such individuals.

It also happens to be the name of the English dementia strategy, which was introduced by the last Government in 2009. Dementia as a policy plank now in England has full cross party support, and the current ‘Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge’ is due to come to an end next March 2015.

In the panel session above, somebody asks whether a dementia diagnosis should ever be withheld from a person with dementia. Kate Swaffer, living with dementia herself, believes firmly ‘no’, saying that one would never dream of withholding a diagnosis of cancer.

Policy in this jurisdiction and others has given due attention to whether the person receiving the diagnosis of dementia actually benefits – put simply is it ‘disabling’ rather than ‘enabling’.

Does it shut more doors than it opens?

But even if one takes the view that dementia is a disability which one is perfectly entitled to do on reading the case law surrounding the Equality Act (2010), the issue of making reasonable adjustments around this particular disability then becomes not a trivial one.

Richard Taylor elegantly advances this argument. Big Pharma have been impressively unimpressive in the offerings for dementia, although some report some substantial short-term symptomatic benefit for symptoms.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) have stated clearly that such medications do not slow the progression of the condition.

But they did offer very recently some enormously useful guidance on supporting people to live well with dementia.

And this issue is a push-pull one. Given the relative inefficacy of the medical interventions, one is possibly attracted to the things one might do to promote living well with dementia.

In a world of ‘whole person care’, where there might be care coordinators helping to break down the silos of service provision for people living with dementia, we might arrive at a destination where people with dementia do receive some help.

This might include assistive technologies, other innovations, or access to advocacy services.

And for a person who has received a diagnosis of dementia, Richard Taylor argues that trust is pivotal. This is somewhat related to Kate Swaffer’s views that ‘support groups’ (for carers) might inadvertently encourage division.

Whilst members of the support and care network clearly have substantial ‘needs’, not least in behavioural and psychological considerations, promoting quality of life for people living with dementia is clearly going to be a vital policy plank for the future.

Some inroads have already been made, as I recently discussed here, but there is a lot yet further still to do I feel.

5. There is more to the person than the dementia.

This is an extremely important message. I sometimes feel that medics get totally lost in their own clinical diagnoses, backed up by a history, examination and relevant investigations; and they become focused on treating the diagnosis rather than the person with medications. But once you’ve met one person living with dementia, you’ve done exactly that. You’ve met only one person living with dementia. And it is impossible to generalise for what a person with Alzheimer’s disease at a certain age performs like. We need to get round to a more ‘whole person’ concept of the person, in not just recognising physical and mental health but social care and support needs, but realising that a person’s past will influence his present and future; and how he or she interacts with the environment will massively influence that.

There’s more to a person than the dementia.

In 1992, the late Prof Tom Kitwood founded Bradford Dementia Group, initially a side-line. Its philosophy is based on a “person-centred” approach, quite simply to “treat others in a way you yourself would like to be treated”.

A giant in dementia care and academia, I feel he will never bettered.

His obituary in the Independent newspaper is here.

Personhood is the status of being a person. Its importance transcends medicine, nursing, policy, philosophy, ethics and law even.

Kitwood (1997) claimed that personhood was sacred and unique and that every person had an ethical status and should be treated with deep respect.

A really helpful exploration of this is found here on the @AlzheimerEurope website.

Personhood in dementia is of course at risk of ‘paralyis by analysis’, but the acknowledgement that personhood depends on the interaction of a person with his or her environment is a fundamental one.

Placing that person in the context of his past and present (e.g. education, social circumstances) is fundamental. Without that context, you cannot understand that person’s future.

And how that person interacts with services in the community, e.g. housing associations, is crucial to our understanding of that lived experience of that person.

All this has fundamental implications for health policy in England.

Andy Burnham MP at the NHS Confederation 2014 said that he was concerned that the ‘Better Care Fund’ gives integration of health services a ‘bad name’.

It is of course possible to become focused on the minutiae of service delivery, for example shared electronic patient records and personal health budgets, if one is more concerned about the providers of care.

Ironically, the chief proponents of the catchphrase, “I don’t care who is providing my care” are actually intensely deeply worried about the fact it might NOT be a private health care provider.

Person-centered care is an approach which has been embraced by multi-national corporates too, so it is perhaps not altogether a surprise that Simon Stevens, the current CEO of NHS England, might be sympathetic to the approach.

Whole-person care has seen all sorts of descriptions, including IPPR, the Fabians, and an analysis from Sir John Oldham’s Commission, and “Strategy&“, for example.

‘Whole person care’ would represent a fundamental change in direction from a future Government.

Under this construct, social care would become subsumed under the NHS such that health and care could be unified at last. Possibly it paves the way for a National Care Service at some later date too.

But treating a person not a diagnosis is of course extremely important, lying somewhat uneasily with a public approach of treating numbers: for example, a need to increase dementia diagnosis rates, despite the NHS patient’s own consent for such a diagnosis.

I have seen this with my own eyes, as indeed anyone who has been an inpatient in the NHS has. Stripped of identity through the ritualistic wearing of NHS pyjamas, you become known to staff by your bed number rather than your name, or known by your diagnosis. This is clearly not right, despite years of professional training for current NHS staff. This is why the campaigning by Kate Granger (“#hellomynameis”) is so important.

It is still the case that many people’s experiences of when a family relative becomes an inpatient in the National Health Service is a miserable one. I have been – albeit a long time ago – as a medical student on ward rounds in Cambridge where a neurosurgeon will say openly, “He has dementia”, and move onto the next patient.

So the message of @DementiaFriends is a crucial one.

Together with the other four messages, that dementia is caused by a diseases of the brain, it’s possible to live well with dementia, dementia is not just about losing your memory, dementia is not part of normal ageing, the notion that there’s more to a person than the dementia is especially important.

And apart from anything else, many people living with dementia also have other medical conditions.

And apart from anything else, many people living with dementia also have amazing other skills, such as cooking (Kate Swaffer), fishing (Norman McNamara), and encouraging others (see for example Chris Roberts’ great contributions to the community.)