The famous ‘Two cultures’ speech was delivered in 1959 at the Senatre House in Cambridge by CP Snow, controversially on the growing schism (growing since the Industrial Revolution, at least) between the arts and sciences.

Coincidentally, 37 years later, I did finals in the same location in neuroscience for my Bachelor of Arts degree, with a mind to do a PhD in young onset dementia at Cambridge (which I then did).

I was really struck by the “two cultures” yesterday. In an ideal world, we shouldn’t have to fight about it – but as some will tell you on one particular political side, money does not grow on trees, but curiously there always seems to be enough money for certain types of research.

I found the Horizon programme on a cure for dementia good in as far as it went. It wasn’t really on a cure for dementia, but mainly an advert for some grant programmes in biomedical research in Alzheimer’s disease.

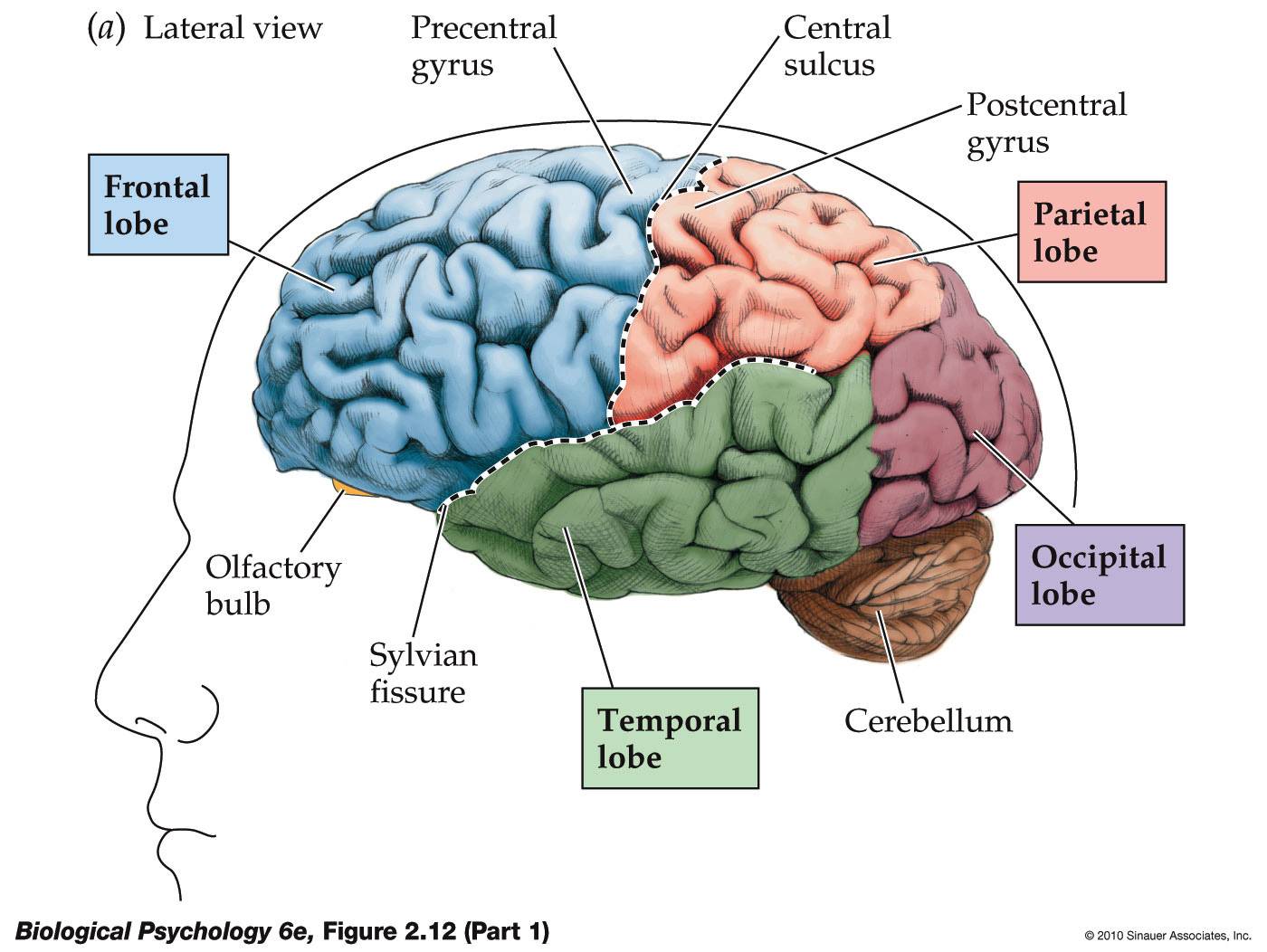

Nick Fox, now a Professor at Queen Square and Director of the Dementia Research Centre there, but who was getting towards the end of his protracted time as Specialist Registrar to Prof Martin Rossor when I was a junior there, explained how voxel based morphometry (specialised brain scanning) could be used to confirm a case of posterior cortical atrophy, previously undiagnosed.

The pitch though was entirely to miss the point. It would have been much more helpful to know what the precise rehabilitative offering for the patient with posterior cortical atrophy was – the patient himself described his own vision as “a jumble” in his own words.

There was hurried talk of tau markers in the cerebrospinal fluid. But a lumbar puncture is an invasive procedure. And a cure which could stop the building up of toxic tau would have been useful to discuss, but Fox totally skirted around what the benefit of his hard won diagnosis was.

If you take the view that the precise name of the dementia is relevant, but the dementia is merely a pathological description of a buildup of tau in the brain somewhere, that helps you with your sledgehammer approach of taking an anti-tau drug forward. Then it means Fox should have entered into some sort of debate as to whether we are all ‘tauopathies’ now, ranging from Alzheimer’s disease, to frontotemporal dementia or posterior cortical atrophy.

Does this make the underlying genetic basis irrelevant? I think somewhat the arguments that posterior cortical atrophy is a variant of Alzheimer’s disease have always been rather anaemic, without reference to why there is such selective neuronal degeneration in the visual parts of the brain, and without reference to the underlying commonalities in genetics basis.

But the problem for Fox with his ‘dementia can be spotted now a decade before symptoms approach’ is the lack of answer to what proportion of people with slightly aberrant brain scans or markers, at what time, would be taken forward for a possible therapeutic treatment.

We saw elsewhere a different person, made patient, through apolipoprotein genotyping, who had become quite distressed about the lack of genetic counselling.

The actual situation for Fox is that there are hundreds or thousands of neurologists or general medics who do not even know what the clinical presentation of posterior cortical atrophy is, so it is no wonder that such patients both here and abroad get taken round the houses, invariably through an ophthalmologist or eye clinic, over years, prior to a diagnosis.

The programme was predictably full of ‘sufferers’ and ‘devastating’, shock doctrine stuff, rather than ANY acknowledgement of any people with dementia leading fulfilling lives. I don’t have any ideological problem with people crying on TV as it represents an authentic emotion.

The narrative however was fraudulently set up as an epidemic of dementia – despite the fact it is now widely conceded that the prevalence of dementia is falling – and here’s the sunny uplands of cure to solve everything. It was good to see cognitive neurorehabilitation get a mention though, even though it was essentially bordering on window dressing.

Quality of care research would be desirable too, as well as good quality of life research.

This was yesterday’s headline in the Times.

The problem was made more graphic with genuinely horrific stories from the Health Ombudsman’s report on poor quality of elderly hospital care, focusing on delayed discharges. But the data hailed from 2014/5, that’s a good two or three years after the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge, one year prior to the Prime Minister claiming he wanted the UK to be ‘the best country to have dementia in by 2020′ in a completely deluded manner, with social care funding on its knees.

The social model of disability correctly admonishes calling all people with dementia as ‘sufferers’ or ‘victims’, but rather holds them to be active participants in citizenship with fundamental human rights, such as a right to dignity. And yet another costly report has shown what we knew already – of people languishing stuck in hospital, who cannot be discharged. We knew all this prior to the last general election too. People have sadly suffered at the hands of the NHS and social care due to mismanagement.

Don’t get me wrong. Biomedical research is important. I followed the tweets from the British Geriatrics Society conference, and one of the tweets involved somebody with dementia who had entered into a coma due to a drug prescribed for delirium. This example shows why it does matter to diagnose some types of dementia (diffuse Lewy Body disease), and the need for clinicians to recognise delirium superimposed on dementia.

A cure for dementia before the onset of symptoms would be remarkable, especially for some rarer young people who face a near-certain likelihood of developing one of the strongly inherited dementias.

But we DO need to face facts, Dementia Awareness Week or otherwise, surely? If we’re ‘curing’ dementia really by focusing on a handful of manageable subtypes such as familial Alzheimer’s disease only, can we ‘solve’ inequitable delayed discharges too for an increasing number facing Jeremy Hunt’s NHS?