“Dementia Rights” is a social action movement that aims to increase understanding of the importance of rights and dementia and inspire people to take action to promote these rights in the community.

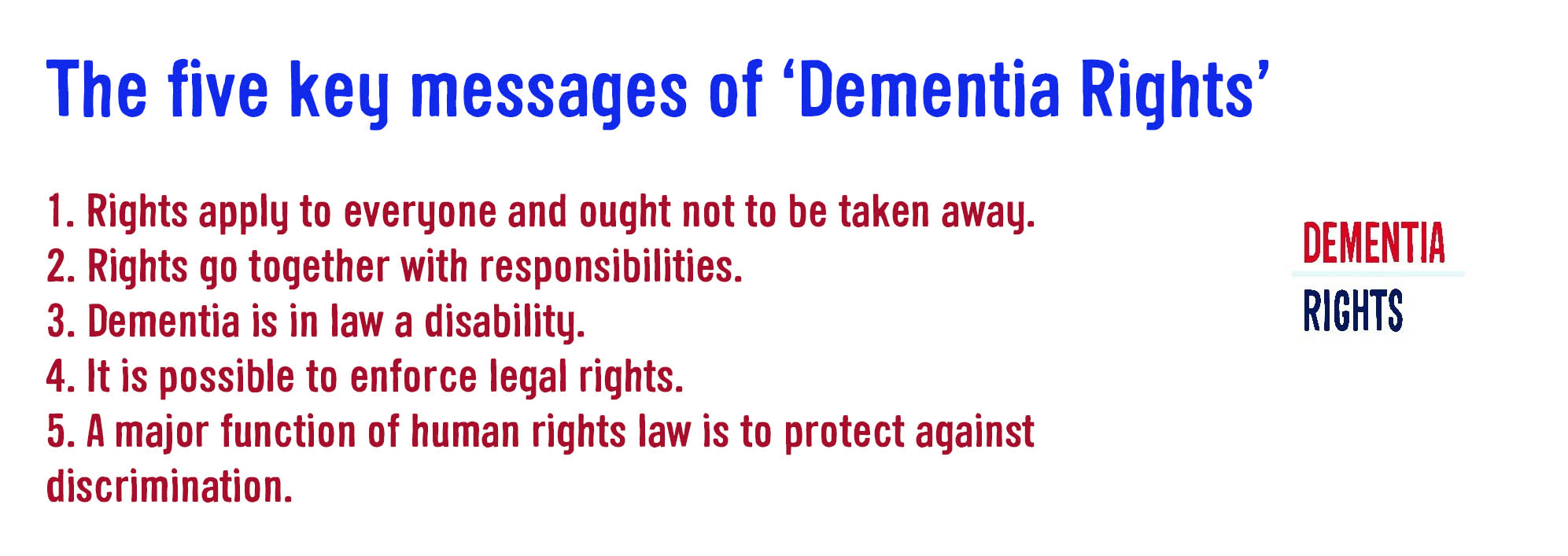

To become a Dementia Rights Supporter, all you need to do is learn five key messages that we think everyone should know about dementia and rights in any country, and then commit to take an action which promotes rights in dementia.

1. Rights apply to everyone, and ought not to be taken away.

The 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights is by far the most widely accepted definition of human rights, encompassing civil and political as well as economic, social and cultural rights.

Human rights are relevant to all of us, not just those who face repression or mistreatment. They protect you in many areas of your day-to-day life. So – in summary, key qualities of human rights have been agreed upon by the international community.

Rights can never be taken away, although they can sometimes be restricted – for example if a person breaks the law, or in the interests of national security.

It has been agreed that human rights must be recognised as:

- Universal: they belong to all of us, to everybody in the world

- Inalienable: they cannot be taken away from us

- Indivisible and interdependent: governments should not be able to pick and choose which are respected. Rights go together with responsibilities.

2. With rights go together with responsibilities expected of individuals.

With rights come responsibilities expected of individuals. “Qualified rights” are rights which require a balance between the rights of the individual and the needs of the wider community or state interest. These inclue: the right to respect for private and family life, the right to manifest one’s religion or beliefs, or freedom of expression.

3. Dementia is in law a disability.

A mental health condition is considered a disability if it has a long-term effect on your normal day-to-day activity. There are many different types of mental health condition which can lead to a disability, including dementia. Dementia is one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people worldwide.

Under article 9 of an international instrument called the UN Convention of Rights for People with Disabilities, all people with disabilities have the right to access all aspects of society on an equal basis with others including the physical environment, transportation, information and communications, and other facilities and services provided to the public.

4. It is possible to enforce legal rights.

Rights can be used in real life locally and have some “teeth”. Legal provisions in equality and human rights are enforceable in a number of countries, either directly or indirectly.

5. A major function of human rights is protect against discrimination.

Disability comes under this as a ‘protected characteristic’, and dementia is a disability. People are not allowed to discriminate because they have any of the protected characteristics. There is also protection against discrimination where someone is perceived to have one of the protected characteristics or where they are associated with someone who has a protected characteristic. Discrimination means treating one person worse than another because of a protected characteristic (known as direct discrimination) or putting in place a rule or policy or way of doing things that has a worse impact on someone with a protected characteristic than someone without one, when this cannot be objectively justified (known as indirect discrimination).