There has been a disturbing tendency for the word ‘social movements’ to become bastardised for marketing a theme or even business product. I sympathise with people needing to pay their mortgages, but this approach has been to the detriment of real participation of those people whom Prof Edgar Cahn referred to as ‘no more throw away people’. Slick marketing, like pornography for the US Supreme Court, can indeed be spotted a mile off – you recognise it when you see it.

The word ‘co-production’ faces a similar setback. However, it is actually quite hard to escape what co-production really means, as defined below as an example.

“Co-production means delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their families and their neighbours. Where activities are co-produced in this way, both services and neighbourhoods become far more effective agents of change.”

(Boyle et al., 2010).

Fake ‘involvement’ of patient groups I think does quite a lot of damage. This at one level is the notorious ‘zero sum gain’ – in that resources consumed A deprives resources for B. As an example, it would be dead easy for Big Charity to donate money to the Dementia Alliance International, a group run by and run for people living with dementia. But the fact this does not readily happen is an epiphenomenon entirely of the need of Big Charity to retain control as to who writes the script. Or put another way, who is in the room.

But secondly an illusion of control is deeply fraudulent in itself. The “illusion of control”, defined as various forms, is the tendency for people to overestimate their ability to control events; for example, it occurs when someone feels a sense of control over outcomes that they demonstrably do not influence.

There are some well known examples of this.

You in an orchard, and you choose an apple which tastes delicious. You assume you are very skilled at choosing apples (when in fact the whole batch happens to be good today).

Another good example is that you enter the National Lottery and in fact you win millions. You assume that this is (partly) a result of how good your lucky numbers are. However, lotteries are totally random so you can’t influence them with the numbers you choose. Although most of us acknowledge this as a statement of fact rather than an opinion, we still harbour an inkling that maybe it does matter which numbers we choose).

Available evidence suggests that an important factor in development of this illusion is the personal involvement of participants who are trying to obtain the outcome (reviewed by Yarritu, Matute and Vadillo, 2014).

It is possible that pseudo involvement or pseudo engagement through regional working groups might be doing more damage than active democracy. I think a tell-tale sign of this is when in a double act of a person with dementia and a person without dementia the person without dementia does nearly 50% (or more) of the talking.

Another good example is where in ‘involving a person with dementia’, there is a “working group” chaired by, and the agenda set by, a person without a dementia. That person without dementia is in full control of the narrative.

This illusion of control has been discussed extensively elsewhere.

“Such involvement is frequently held up as empowering audiences and enhancing democracy. Indeed, the possibility of audiences creating their own content has led to the idea of reconceptualising traditional consumers as, in Jay Rosen’s now famous definition, ‘the people formerly known as the audience’. But what is being offered is a ‘simulacrum’ of engagement. The user is given the illusion of control – while all the time the underlying power relationships remain unchallenged. It has become commonplace to argue that policy-makers should act to ‘increase citizens’ participation in the commissioning and production of news in order to ensure that “the public interest” is no longer defined in private’ (for example Co-ordinating Committee for Media Reform 2012). How this might be achieved is less than clear and the belief that it will increase plurality may be ill-founded’.

(Scullion et al., 2013)

The traditional approach to the work on the “illusion of control” has been framed in motivational terms (e.g., Langer, 1975).

From this perspective, people’s judgments of control are influenced by subjective needs related with the maintenance and enhancement of the self-esteem (e.g., Heider, 1958). And as such it might be better to call involvement initiatives for what they also achieve – peer-support as well as boosting people’s self confidence in talking at public events.

It has been shown that the sense of having control has benefits for well-being (e.g., Bandura, 1989; Lefcourt, 1973).

As Bandura (1989) writes:

“They are full of impediments, failures, adversities, setbacks, frustrations, and inequities. People must have a robust sense of personal efficacy to sustain the perseverant effort needed to succeed. Self-doubts can set in quickly after some failures or reverses. The important matter is not that difficulties arouse self-doubt, which is a natural im- mediate reaction, but the speed of recovery of perceived self-efficacy from difficulties.”

This reflects a personal adage of mine – it’s not how you fall, it’s how you get up. And also makes complete sense – in that the invitation to go to events or conferences acts as a counterpoint to being given a diagnosis of dementia which has potentially a profound impact on identity.

But Kate Swaffer’s construct of ‘prescribed disengagement’ is significantly more relevant here, I feel.

Undeniably, one must set one’s sights way above “involvement”.

Promoted by the Scottish jurisdiction notably, a human “rights based approach” is about empowering people to know and claim their rights and increasing the ability and accountability of individuals and institutions who are responsible for respecting, protecting and fulfilling rights.

There are some underlying principles which are of fundamental importance in applying a human rights based approach in practice. These are the so-called PANEL principles.

participation

accountability

non-discrimination and equality

empowerment and

legality.

And these remain relevant too to the actual way care and support are approached.

As the Scottish Human Rights website explains,

“Everyone has the right to participate in decisions which affect their human rights. Participation must be active, free, meaningful and give attention to issues of accessibility, including access to information in a form and a language which can be understood.

In relation to the care of older people this means that individuals should participate in all decisions about the care and support they are receiving. This could range from participation in the commissioning and procurement of social care services by local authorities to participating in daily decisions about the care and support being received.”

Latterly, there has been such enormous arrogance that consistently people with dementia, if invited to conferences about dementia at all, are invited at the last minute giving all the semblance of an ‘after thought’ for marketing purposes.

One wonders why the named speakers in the programme are so reluctant to keep up a fuss, even those who have an involvement string to their bow.

Exclusion is no laughing matter parodies excepted.

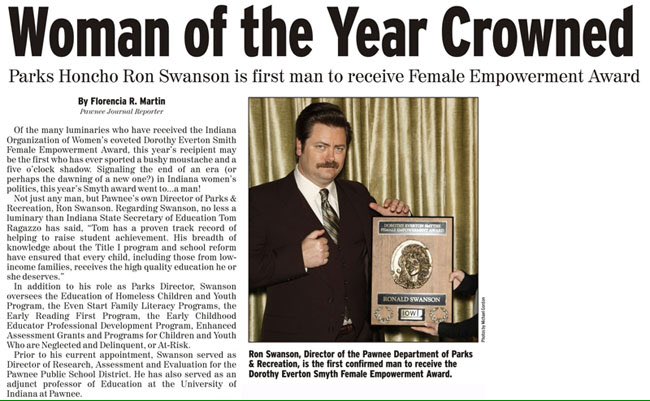

Take for example a woman of the year who is in fact a man (though please note that this is a joke).

But this sadly is not a joke. One year ago, Saudi Arabia hosted an all-male ‘women’s rights’ conference as reported here.

The article notes that:

“Saudi Arabia’s laughably prestigious University of Qassim played host to one of the biggest women’s rights conferences in the Arab world in 2012. Ironically, the institution managed to hold the event without the advice or attendance of a single woman.”

In the market which has developed in health and social care, it has been convenient to formalise the ‘invisible hand’ of Adam Smith into a broker. But questions about whether there is such a thing as a free broker, or whether fake involvement is seriously damaging to your genuine participation, must surely be asked.

References

Bandura A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175.

Boyle, D, Coote, A, Sherwood, C, Slay, J. (2009) Right here, right now: Taking co-production into the mainstream. NEF/NESTA/The Lab.

Heider F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relation. New York, NY: Wiley.

Langer E. J. (1975). The illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 311–328. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.32.2.311

Lefcourt H. M. (1973). The function of the illusions of control and freedom. American Psychologist, 28, 417–425. doi: 10.1037/h0034639.

Scullion, R, Gerodimos, R, Jackson, D, Lilleker, D. (2013) The Media, Political Participation and Empowerment. Routledge Publishers.

Yarritu I, Matute H, Vadillo MA. Illusion of control: the role of personal involvement. Exp Psychol. 2014 Jan 1;61(1):38-47. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169/a000225.