In the words of Ian Dury and the Blockheads, there are indeed “reasons to be cheerful” about the English dementia strategy. We need a strategy, but we need to think about the imperative for “the cure” while appearing to neglect finer details of care. Furthermore, the actual quality, as well as quantity, of diagnosis merits scrutiny.

The need for a strategy

Our English dementia strategy has some key prongs from the clinical perspective – prevention, diagnosis, care, support, palliative care/end of life approaches and cure. How these components are balanced has practical implications for funding and resource allocation. Underpinning this is the need for high quality research, in both cure and care, qualitative and quantitative, non-molecular and molecular, and so on.

England currently does not have an up-to-date dementia strategy. The last ‘five year plan’ expired in 2014, and was supposed to be renewed. Baroness Sally Greengross, the previous chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group on dementia, made clear many times that the intention would be to recapitulate what had worked (or not) in the document from 2009 before progressing. This work, if indeed done, has never been published to the best of my constructive knowledge.

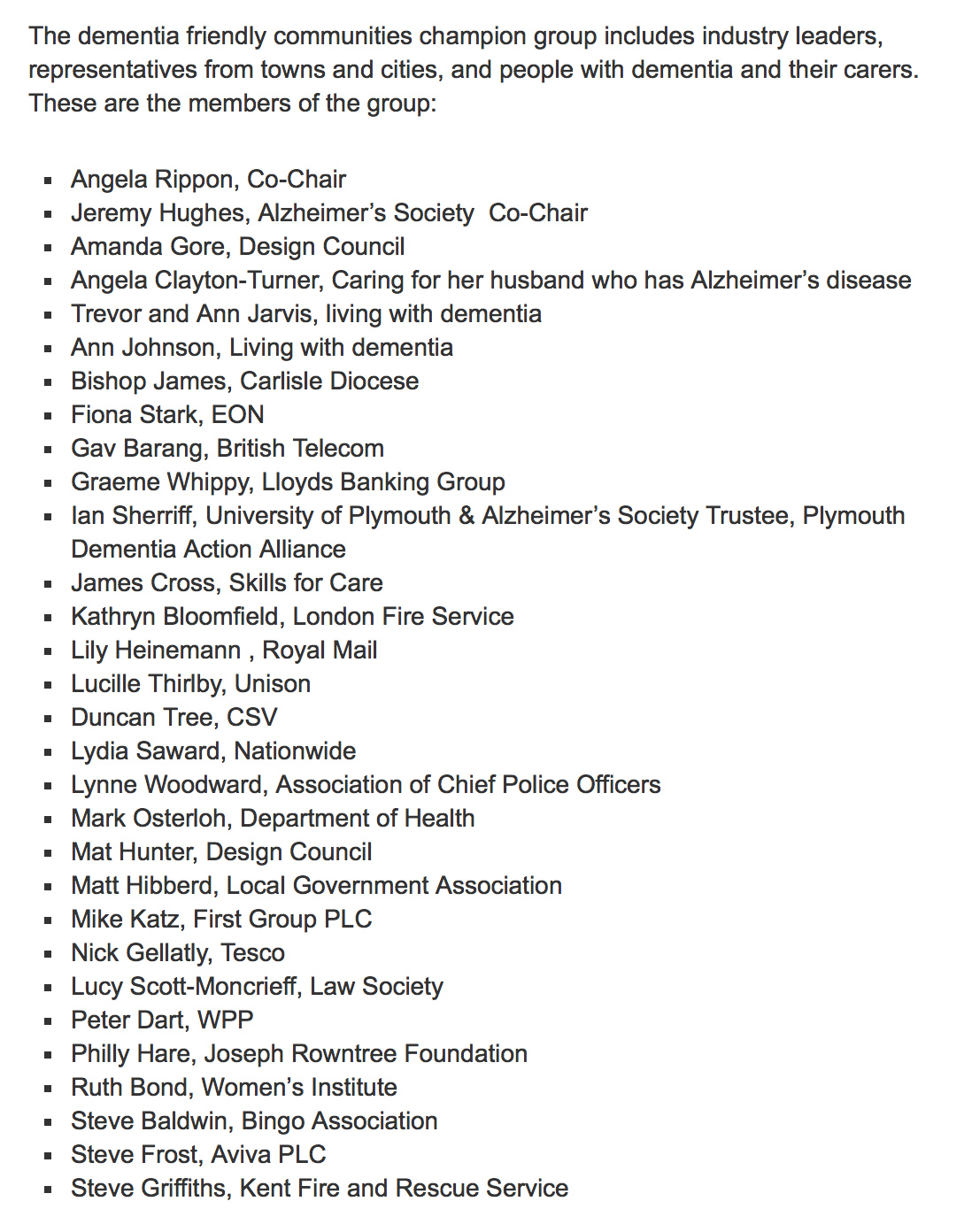

There are regional differences in national strategies, although the benefits of national plans have been described at great length elsewhere (an initiative spearheaded by the charity Alzheimer’s Disease International). Many feel that the first and only English strategy to be published by the Department of Health so far, entitled “Living well with dementia”, is very heavily weighted towards diagnosis and combating stigma through initiatives such as ‘dementia friendly communities’. This is in comparison, say, with the Australian jurisdiction which emphasises, it is said, primary care.

Karen Dening last year mentioned in the Dementia Congress in Telford that cooking dementia policy was ‘like cooking a cake’. Karen who is Director of Admiral Nursing for the leading charity Dementia UK, explained that making a cake required an understanding of the fine balance of ingredients. Too much of one ingredient (or too little) could, in theory, “spoil the cake”.

The importance of the cure but at what cost?

Indeed, the meme “care for today, cure for tomorrow” does merit scrutiny. Take ‘the cure bit’ for a start. In the same way that medicine might provide a cure for a type of cancer, such as an aggressive haematological condition, it might provide a cure for a type of dementia. In other words, in reality, the ultimate “cure for dementia” is likely to arrive in an incremental, piecemeal, gradual fashion for different types of dementia. And the unexpected might happen – for example, immunomodulators might find a ‘new market’ disruptively in the “fight against dementia”.

As such, you don’t ‘cure a headache’ with radical neurosurgery consequent upon sophisticated neuroimaging. You are likely to treat the symptom with a paracetamol. And the same logic goes for asthma and bronchodilators.

In the history of drug development for dementia, the debris of “repeated and costly failures” is a formidable one. But then again it is argued that no omelette was ever made without cracking eggs. It is said, for example, that between 1998 and 2012, there were 101 unsuccessful attempts to develop drugs for Alzheimer’s disease, with only three drugs gaining approval for treating symptoms of the disease.

In the phase before the theoretical obliteration of dementia in some future year, it is likely that care will also be required for tomorrow as well. This is because in someone who is being tried on an orphan drug for dementia a management strategy is likely to include also cognitive techniques, such as cognitive stimulation therapy, currently being examined for the NICE guidance on dementia to be published soon.

Nonetheless, any cures for dementia are to be welcomed not least because they offer hope. The worry, of course, is that there is a “zero sum gain”, in that if people are reaching for their pockets to fund research charities they are less inclined to fund social care for people living with dementia for today.

We have to talk about care

Even with talk of “precepts” from the Budget of last year, social care, not having been ringfenced since 2010, is still on its knees. Public health, which is supposed to deliver the risk mitigation strategy, for dementia has also been an unwise cost saving.

Social care is not essentially about bailing out the NHS in its ‘funding deficit’. It is as a profession concerned about enabling and protecting its client group. I feel few areas are as important as dementia for this.

Dementia, unlike cancer, has no specified “care pathways”. There are more than a hundred causes of dementia, depending on how you count them, and indeed every person with dementia is a unique individual. Integrated person-centred care pathways, and advance care planning especially in light of substantial comorbidities (involving of course carers), would do much to mitigate against the confusion and uncertainty which often accompanies the subsequent trek of a person with dementia through the maze of services.

The minimisation of the rôle of clinical specialist nurses, unlike cancer, is a deeply embarrassing one. The repercussions on the weaknesses in pursuant policy, including continuity of care in different care settings and delivery of palliative and end-of-life approaches, are glaringly obvious to clinicians currently working in dementia care today.

Prevention and seeking the diagnosis

The ‘healthy body, healthy mind’ campaign makes sense in a view that the prevalence of dementia in England has been said to be falling. There are of course exceptions to every rule. We are all aware of people who’ve completed a healthy treadmill stress test for angina, without problem, only to fall dead in the car park. Being educated, described as reducing your risk of dementia, did not stop Dame Iris Murdoch or Baroness Margaret Thatcher developing dementia. But progression also means preventing dementia progressing at a fast rate – in the future, maybe wearables and other technology might help in real time.

How a person or their closest ones seek a medical diagnosis for dementia was not straightforward, even before NHS England introduced its disastrous, and ultimately temporary, initiative to provide financial incentive for the diagnosis of dementia. A lot depends on the coping strategies of the people seeking diagnosis, as well as whether the benefit of a diagnosis is more beneficial than any ensuing stigma.

Many people report being “terrified” of then going to memory clinic, and a long wait is akin to ‘justice delayed is justice denied’. But an accurate diagnosis of dementia is important ultimately. General practitioners, already facing a bureaucratic and demand tsunami, may not have adequate resources or training necessarily to feel comfortable, although there is no reason why general practitioners cannot be also the ‘specialists’ making the diagnosis.

But likewise, people with unexplained symptoms, languishing without a diagnosis, is not on. People do deserve to know what medical diagnoses might apply to them. Physicians and other professionals would prefer people living with dementia not to be propelled into a crisis or move to residential setting involuntarily.

Furthermore, there is a school of thought that a correct diagnosis of dementia sums up the notion ‘knowledge is power’. Armed with the information, you can make reasonable adjustments just as for any physical disability, for example memory or visual aids, better signage around your accommodation. It gives you better bargaining power as an upholder of disability rights, as well as gives you specific opportunity to plan for the future, for example power of attorney or will, (on legal loss of capacity or ultimately death.)

Whilst there is a huge emphasis on diagnosis in current English dementia policy, there is consensus that the quality of how the actual diagnosis is closed could be improved in very many cases even now (see an excellent review here).

Conclusion

With so many vested interests involved, the cooking of this particular cake is bound to be complicated. But hopefully with time issues will become much clearer. This is ultimately for the benefit of persons with dementia and their closest ones.

[The author, Dr Shibley Rahman, of this blogpost (@dr_shibley) is an academic physician specialising in dementia. BBC Radio 4 will air a programme in the ‘File on 4′ series entitled “Has a drive to increase the diagnosis and find a cure been effective?’ at 20.00 on 23rd February 2016, presented by Deb Cohen (producer, Paul Grant). Details of this episode of File on 4 are on the BBC website here.]