Andy Tysoe tweeted this only this morning.

More fantastic proportionate health reporting & awesome news for WORMS!@Minghowriter @dr_shibley @TommyTommytee18 pic.twitter.com/0zKDoi73ug

— andy.tysoe (@dementiaboy) February 13, 2016

The sheer number of the ‘breakthroughs’ in dementia treatments has been breathtaking in the last few years, particularly since 2012. This of course is a highly manipulative agenda. The aim of this propaganda is to convince you that progress is being made in dementia research, and that you should continue to fund it. The truth is – the vast majority of the breakthroughs are useless.

Nevertheless, we are where we are. Social care funding has not been ringfenced in England since 2010. You are not going to get any stories about this on a frequent basis. English dementia policy needs an infrastructure for coherent integrated person-centred care, with a trained workforce, and care pathways. One large charity pumping out ‘Friends’ is not enough. The same charity has decided to campaign on #FixDementiaCare with cheap tacky photoshoots from MPs, having been ineffective on the issue in the last few years. One should legitimately be asking for stronger clinical leadership this being the case. The English dementia strategy expired five years after 2009 – it is now 2016.

Language sets the political agenda everywhere.

Even words such as ‘engagement’ and ‘involvement’ compound the impression of ‘does he take sugar?’ All too often people with dementia have been speaking in public on the subject of being engaged in events on dementia, rather than real issues in dementia policy – such as the need for funding in social care. Organisers of events invite people with dementia at the last minute, with this act of tokenism being highly insulting in effect. Working groups if the participation at worst is illusory might add a further layer of marketing, and often appear like a nice little earner, potentially, for the bureaucrats organising them. But the real effect is far more damaging – this friendliness has been profoundly disempowering, and highly obstructive. Often the purported ‘co-production’ and the ‘patient voice’ are not genuine at all – the relationship defined by Nesta in 2009 is defined by three simple words “equal and reciprocal”, often forgotten, and becomes a trite trivial piece of marketing, sadly, instead.

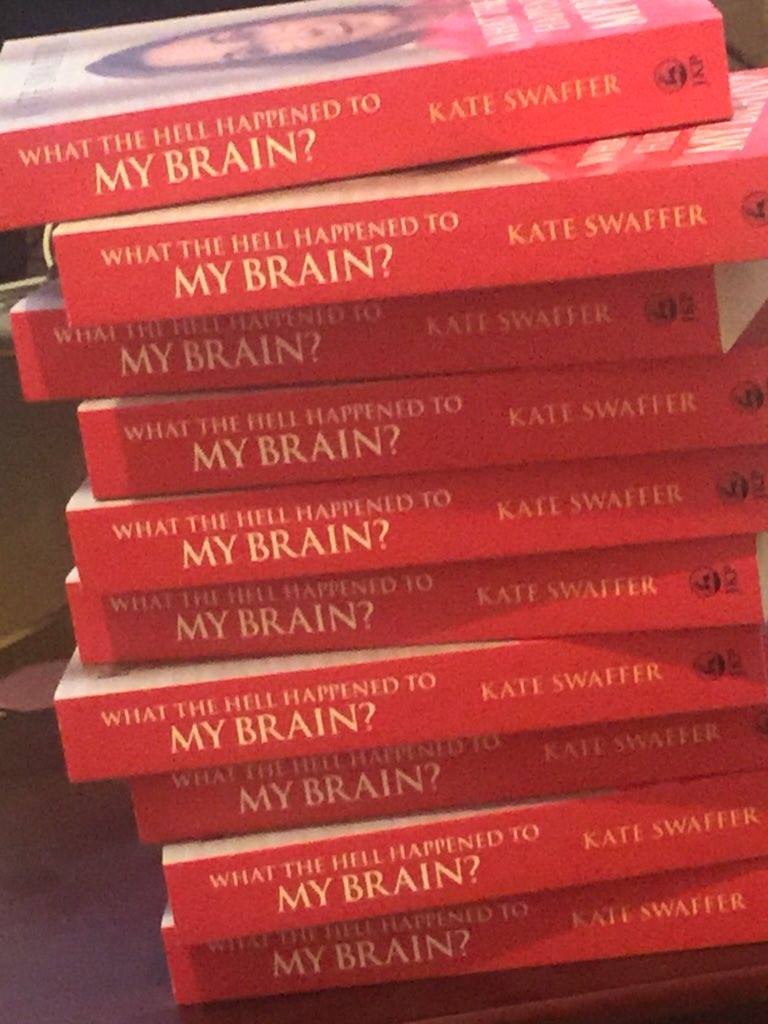

Compare this to a whole book on the subject written by Kate Swaffer, “What the hell has happened to my brain?”.

I have been dumbfounded and truly enormously saddened by those who claim to be gurus in engagement and involvement being so silent on Kate’s book. But this for me speaks volumes.

Kate, not only living with dementia, is about to embark on a Ph.D. Whilst medics go all Captain Cavemen mode about the number of diagnoses (of whatever quality) they’re making, Kate is demonstrating what should be happening. That people living with dementia should be given every single resource to help them live ‘beyond the diagnosis’ as Kate calls it, I feel strongly, is an essential imperative in both domestic and international policy in dementia. This change to a rights-based approach, viewing dementia as a disability, has totally changed the mood music.

Here’s the original paper we did with others on language and dementia some time ago; it was in fact my second ever poster at an international conference on dementia (though I have done considerably more now.)