This week, the first two ever Dementia Rights Champions will give their first information sessions in the innovative ‘Dementia Rights’ programme.

Dementia Rights is a novel, innovative programme designed not just to dispel the stigma and prejudice which can surround dementia, but also is supposed to be of practical help to people living with dementia in the UK to help ‘unlock’ their rights.

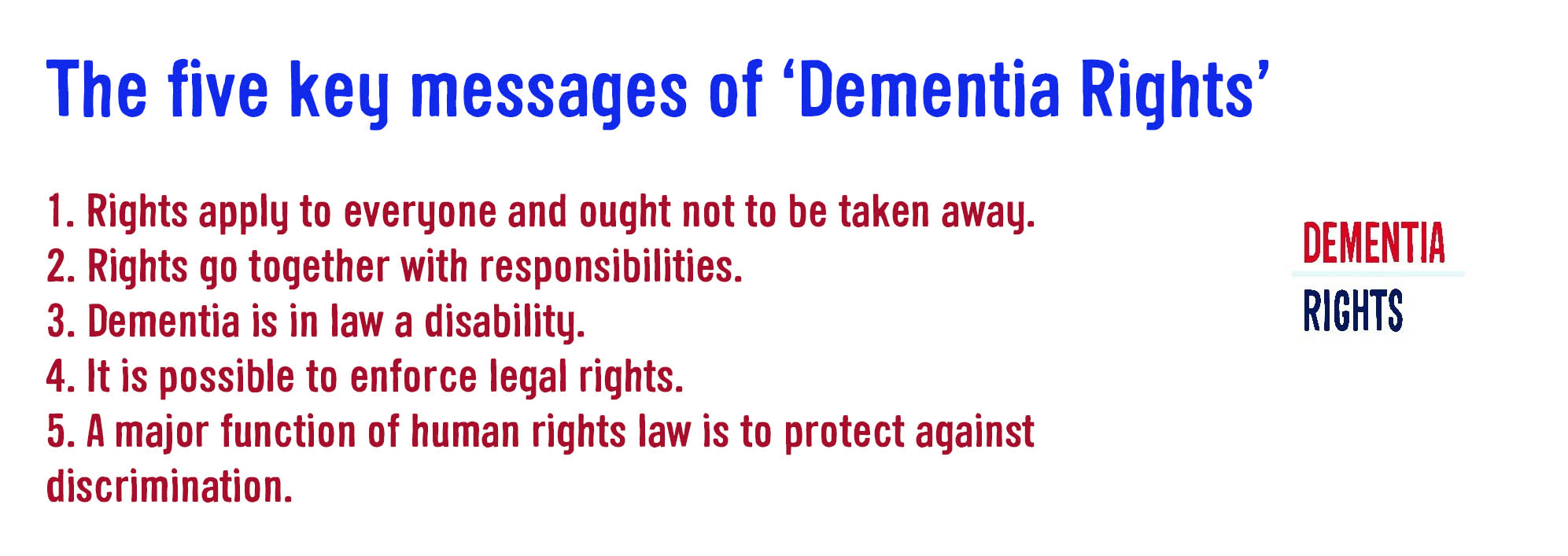

Dementia Rights information sessions are about 45-minutes to 60 minutes, and are designed to spread five key messages the Dementia Society thinks everyone should know about rights.

These are shown on their pledge card.

There are currently about 900,000 people in the UK who’ve received a diagnosis of dementia. All of them are defined by their unique identities as persons, not defined by the labels of the dementia diagnosis. The Dementia Friends programme from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England was a social movement launched in 2012 as part of the Prime Minister Dementia Challenge to help to raise awareness of dementia.

One of the key messages in Dementia Friends is that it is possible to live well with dementia. For ‘Dementia Awareness Week’, the Alzheimer’s Society is asking everyone to confront dementia. Their research yet further shows that people are on the whole reluctant to seek a diagnosis. This is possibly due in part to the negative social perception of dementia.

I presented a talk earlier this year in Budapest at the 31st Alzheimer’s Disease International Conference. This talk presented novel survey data on how knowledge of legal rights from domestic and international instruments was generally poor. This lack of knowledge about rights is a major barrier to the widespread adoption of rights internationally, it is felt.

The international stakeholder group of people with dementia “Dementia Alliance International” have led on this rights based initiative to promote rights. As part of campaign, they have been globally concerned with making sure that people know that they can ‘make a difference’. This sense of agency and urgency is pivotal to make rights for dementia a reality. You can support their brilliant work directly here.

There is a growing feeling that rights based advocacy in dementia is not at all about people making money ‘out of opportunities’, and death by powerpoint or commissioning. I have written a pamphlet on the application of rights in England and Wales jurisdiction, which contains general principles of use in other jurisdictions. I am making this work available for free, but this is no replacement for actual legal advice; the pamphlet is clearly meant to be a general introduction to the area.

You can access this pamphlet here

.You can help this Dementia Rights movement, by contacting me if you want to become a Dementia Rights Champion. I’d love to hear from you.