The 2009 English dementia strategy, co-authored by Sube Banerjee, now Professor of dementia at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, and Jenny Owen, then head of social care in Essex, went a long way to providing a road map for a strategy.

This laid down useful foundations, many strands of which were to be embellished tactically under this Government through “The Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge”. In some ways, its major limitations were unintended consequences not fully known at the time.

The English dementia strategy is intended to last for five years, and, as the 2009-14 ‘five years’ come to an end, now is THE right time to think about what should be in the next one. Irrespective of who comes to deliver this particular one, progress has been made with the current one. I believe that across a number of different strands the focus on policy should delivering care, cure or support, according to what is right for that particular person in his social environment at that particular time.

The problems facing the English dementia strategy now are annoyingly similar to the ones which Banerjee and Owen faced in 2008. Whilst they do not have ‘political masters as such’, they can be said to have had some political success. But that should never have been the landmarks by which the All Party Parliamentary Committee, chaired by Baroness Sally Greengross, were to ‘judge’ this strategy document.

The national dementia strategy back in 2009 had three perfectly laudable aims.

The first is to change professional and societal views about dementia.

There was a perception that some Doctors would sit on a possible diagnosis for years, before nailing their colours to their diagnostic mast. So this need for professionals to be confident about their diagnosis got misinterpreted by non-clinical managers as certain doctors, particularly in primary care, being obstructive in making a diagnosis.

At the time, it was perceived that there also had to be an overhaul in the way doctors think about the disease – a quarter believe that dementia patients are a drain on resources with little positive outcome, according to a National Audit Office (NAO) in July 2007. But this has only been exacerbated, and some would say worsened, by language which maintains “the costs of dementia” and “burden”, rather than the value which people with dementia can bring to society.

Associated with this has undoubtedly been the promotion of the message that ‘nothing can be done about dementia’. Indeed, the G8 dementia summit, collectively representing the views of multi-national pharmaceutical companies and their capture within finance, government and research, spoke little of care, and focused on methods such as data sharing across jurisdictions. It’s likely corporate investors will see returns on their investment in personalised medicine and Big Data, but it is essential for the morale of persons with dementia that they are not simply presented as ‘subjects’ in drug trials (and misuse of goodwill in the general public too). Unfortunately, if elements of Pharma overplay their hand, they can ultimately become losers, an issue very well known to them.

High quality research is not simply about excellent research into novel applications of drugs for depression, diabetes or hypertension, or the plethora of molecular tools which have a long history of side effects and lack of selectivity, but should also be about high quality research into living well with dementia. This is going to be all the more essential as the NHS makes a painful transition from a national illness service back to a national health service, where wellbeing as well as prevention of illness and emergency are nobel public health aims.

This summit was presented with an ultimate aim of producing a ‘cure’ for dementia by 2025, or ‘disease modifying therapies’, with no discussion of how ethical it would be – or not be – for the medical profession to put into slow motion a progressive condition; if it happened that the condition were still inevitable. The overwhelming impression of many is that the summit itself was distinctly underwhelming in what it offered in terms of grassroots help ‘on the gound’.

The G8 dementia summit did nothing to consider the efficacy of innovations for living well with dementia, for example assistive technology, ambient assisted living, design of the home, design of the ward, design of the built environment or dementia friendly communities. It did nonetheless commit to wanting to know about it at some later date.

It did nothing to consider the intricacies of the fundamentals of ‘capacity’ albeit in a cross-jurisdictional way, and how this might impact on advocacy services. All these issues, especially the last one, are essential for improving the quality of life of people currently living with dementia.

A focus on the future, for example genetic analysis informing upon potential lifestyle changes one might have to prevent getting dementia at all, can be dispiriting for those currently living with dementia, who must not be led to feel ignored amongst a sea of savage cuts in social care. The realistic question for the next government, after May 7th 2015, of whatever flavour, is to how to catalyse change towards an integrated or ‘whole person’ ethos; ‘social prescribing‘, for example, might be a way for genuine innovations to improve wellbeing for people with dementia, such as ‘sporting memories‘, to gain necessary traction.

Empowering the person living with dementia with more than the diagnosis is fundamental. It is now appreciated that living well with dementia requires time to take care over appreciating the beliefs, concerns and expectations of the person in relation to his or her own environment. This interplay between personhood and environment for living well with dementia has its firm foundations in the work of the late great Tom Kitwood, and has been assumed by the most unlikely of bedfellows in the form of ‘person centred care’ even by multinationals.

Rather late in the day, and this seemed to be a mutual collusion between corporate-acting charities and the media, as well as Pharma, was a volte face on misleading communications about the efficacy of medications used to treat dementia. NICE, although potentially themselves a target of ‘regulatory capture’, were unequivocal about their conclusions; that a class of drugs used to treat ideally early attentional and mnemonic problems in early dementia of the Alzheimer type, had a short-lived effect on symptoms. of a matter of a few months, and did nothing to slow progression of disease. Policy is obligated though to accommodate that army of people who have noticed substantial symptomatic benefits for that short period of time with such medications such as aricept (one of the medications known as cholinesterase inhibitors)? Notwithstanding that, I dare say a medication ‘to stop dementia in its tracks’, as has been achieved for some cancers and HIV/AIDS, would be ‘motivating’, though I think the parallels medically between the dementias, HIV/AIDS and cancer have been overegged by non-clinicians.

And this was after spending many years researching these medications. The opportunity cost of the NHS pursuing the medical model is not inconsiderable if one is indeed wishing to ‘count the cost’ of dementia, compared to what could have been achieved through simple promotion of living well methods.

Large charities across a number of jurisdictions have clearly been culprits, and are likely to be hoisted by their ptard, as organisations as the Dementia Alliance International, a group of leading people living with dementia, successfully reset the agenda in favour of their interests at the Puerto Rico Alzheimer’s Disease International Conference this year.

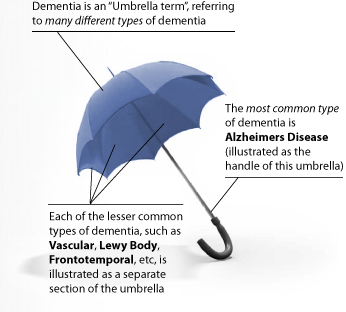

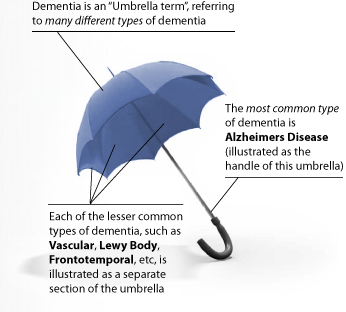

The second problem that still needs addressing is diagnosing the conditions which commonly come under “the dementia umbrella”.

[Source: here]

And clearly, the millions spent on Dementia Friends, a Department of Health initiative delivered by the Alzheimer’s Society, provides a basic core of information about dementia. It has a target of one million ‘dementia friends’, which looks unachievable by 2015 now. This figure was based on Japan, where the social care set-up is indeed much more impressive anyway, and which has a much lager population.

The messages of this campaign are pretty rudimentary, one quite ambiguous. The campaign suffers from training up potentially a lot of people with exactly the same information, delivered by people with no academic or practitioner qualifications in dementia necessarily. This means that such ‘dementia friend champions’ are not best placed to discuss at all the difference between the various medical presentations of dementia in real life, nor any of the possible management steps. Egon Ronay it is not, it is the Big Mac of dementia for the masses. But some would say it is better than nothing.

But has training up so many dementia friends actually done a jot about making the general public into activists for dementia, like being a bit more patient with someone with dementia in a supermarket queue? Dementia Friends clearly cannot address how a member of the general public might ‘recognise’ a person with dementia in the community, let alone be friendly to them, just by mere superficial observation of their behaviour. It is actually impossible to do so – laying to the bed the completely misleading notion that schoolchildren have been able to recognise the hallmarks of dementia in their elders, which have been missed by their local GPs.

This first issue about shifting attitudes in perception and identity of dementia is very much linked to the issue of diagnostic rates. A public accounts committee report in January 2008 had revealed that two-thirds of people with dementia never receive a specialist diagnosis. Only 31% of GPs surveyed by the NAO agreed that they had received sufficient training to help them diagnose and manage dementia, and doctors have less confidence about diagnosing the disease in 2007 than they had in 2004.

Have things fundamentally changed in this time? One suspects fundamentally not, as there has always been a reluctance to do anything more than a broad brush public health approach to the issue of diagnosis.

Goodhart’s law is named after the banker who originated it, Charles Goodhart. Its most popular formulation is: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” The original formulation by Goodhart, a former advisor to the Bank of England and Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics, is this: “As soon as the government attempts to regulate any particular set of financial assets, these become unreliable as indicators of economic trends.”

And now it turns out that recoding strategies are being developed in primary care so as possibly to inflate the diagnostic rates artifactually. But while the situation arises that people in the general public may delay seeing their GP, and thereafter by mutual agreement the GP and NHS patient decide not to go on further ‘tests’, primary care can quite easily sit on many people receiving a diagnosis. The evidence base for mechanisms such as ‘the dementia prevalence calculator’ has been embarrassingly thin.

For example, Gill Phillips gives a fairly typical description of someone ‘worried well’ over functional problems at a petrol pump very recently, but the acid test for English policy is whether a person such as Phillips would feel inclined at all to see a Doctor over her ‘complaints’? The danger with equating memory problems with dementia, for example, means that normal ageing, while associated with dementia, can all too easily become medicalised.

And while there are possibly substantial disadvantages in receiving a diagnosis, both personally (e.g. with friends), professionally (e.g. employment), or both (e.g. driving licence), one should consider the limitations of national policy in turning around deep-seated prejudice, stigma and discrimination. And the solution to loneliness, undoubtedly a profound problem, is not necessarily becoming a ‘Dementia Friend’ if this means in reality getting the badge but never befriending a person with dementia? A ‘point of action’ like donating to a large corporate charity may be low hanging fruit for members of the public and large charities, but I feel English policy should be ambitious enough to consider shifting deep-rooted problems.

Such problems would undoubtedly be mitigated against if any Government simply came clean about what has been the increase in resource allocation, if any, for specialist diagnostic and post-diagnostic support services following this drive for improved dementia diagnosis rates. Lack of counselling around the period of diagnosis, with some people being reported as just being recipients of an ‘information pack’, is clearly not on, as a diagnosis of dementia, especially (some would say) if incorrect, is a ‘life changing event’.

Too often people with dementia, and close friends or family, describe only coming into contact with medical and care services at the beginning and end of their experience of a dementia timeline. Different symptoms, and different medications to avoid, are to be expected depending on which of the hundred causes of dementia a person has; for example Terry Pratchett and Norman McNamara have two very different types of dementia, posterior cortical atrophy and diffuse Lewy Body disease respectively. There is going to be no ‘quick fix’ for the lack of specialist support, though there is undoubtedly a rôle for ‘drop in‘ centres to provide a non-threatening environment for the discussion of dementia, encouraging community networks.

Ultimately, the diagnosis of dementia should be right for the person, at the correct time for him or her. This is the philosophy behind ‘timely’ rather than ‘early’ diagnosis, a battle which certain policy-makers appear to have won at last. Empowering the person living with dementia with that diagnosis can only be done on that personal level, with proper time and patience; ensuring sustainable dignity and respect for that person with a possible life-changing diagnosis of dementia.

The third priority of the strategy inevitably will be to improve the quality of care and support for people once they have been diagnosed.

At one end, it would be enormously helpful if the clinical regulators could hone on their minimum standard of care and those people responsible for care, including management. This is likely to be done in a number of ways, for example through wilful neglect, or the proposed anticipated proposals from the English Law Commission on the regulation of healthcare professionals anticipated to be implemented – if at all – in the next Government.

At the other end, there has been a powerful realisation that the entire system would collapse if you simply factored out the millions of unpaid family caregivers. They often, despite working extremely hard, report being nervous about whether their care is as good as it should be, and often do not consider themselves ‘carers’ at all.

There have clearly been issues which have been kicked into the long grass, such as tentative plans for a National Care Service while such vigorous energy was put into the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge. “Dementia friendly communities”, while an effective marketing mantra, clearly needs considerably more clarification in detail by policy makers, or else it is at real danger of being tokenistic patronisingly further stereotypes. Nobody for example would dare to suggest a policy framework called “Black friendly communities”. Whilst there are thousands of specialist Macmillan nurses for cancer, there’s about a hundred specialist Admiral nurses for dementia.

We clearly need more specialist nurses, even there is some sort of debate lurking as to whether Admiral nurses are ‘the best business model’. However, the naysayers need to tackle head on how very many people, such as those attending the Alzheimer’s Show this weekend in Olympia, describe a system ‘on its knees’, with no real proper coordination or guidance for people with dementia, their closest friends and families, to navigate around the maze of the housing, education, financial/benefits, legal, NHS and social care systems.

A rôle for ‘care coordinators‘ – sometime soon – will have to be revisited one suspects. But it is clearly impossible to have this debate without a commitment from government to put resources into a adequate and safe care, but while concerns about ‘efficiency savings’ and staffing exist, as well as existing employment practices such as zero-hour contracts and paid carers being paid below the minimum wage, how society values carers will continue to be an issue.

At the end of the day, care is profoundly personal, and repeatedly good care is reported by people who have witnessed continuity of care (away from the philosophy of the delivery of care in 15-minute “bite size chunks”). Unfortunately, the narrative in the NHS latterly has become one of business continuity, rather than clinical professional continuity, but this should ideally be factored into the new renewed strategy as well. I feel that this renewed strategy will have to accommodate actual findings from the literature taken as a whole, which is progressing at a formidable rate.

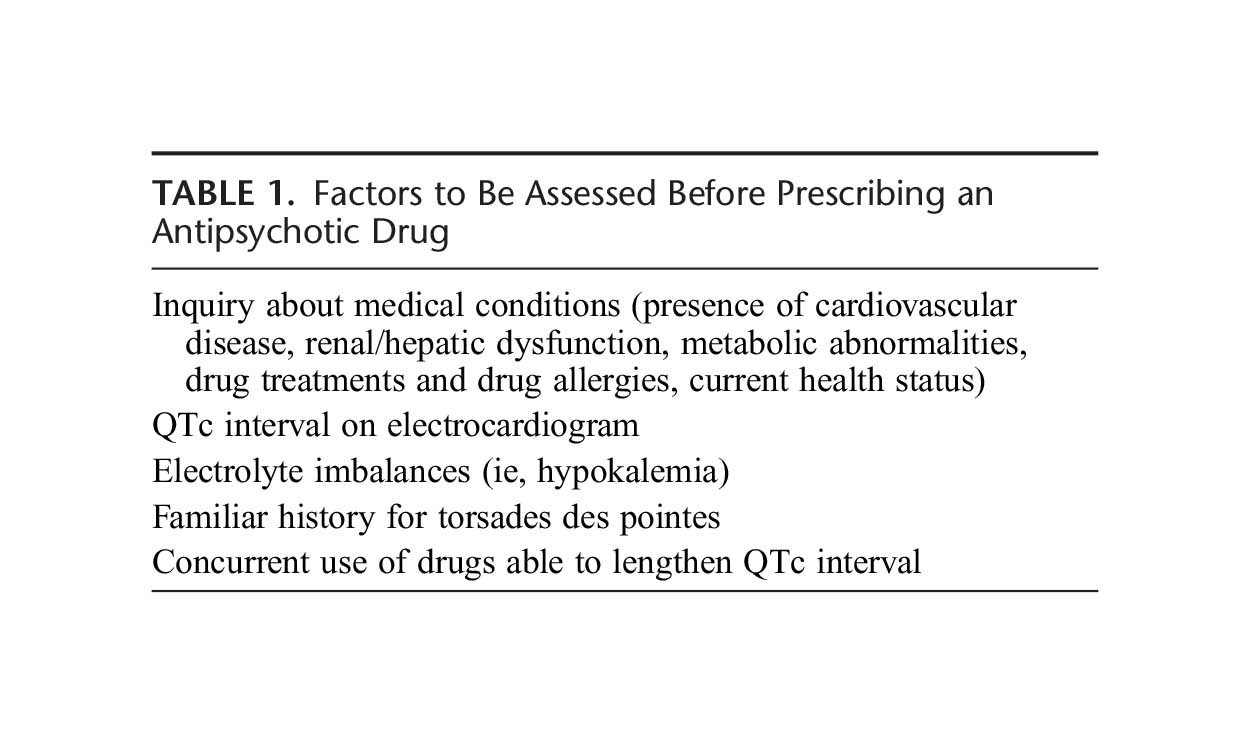

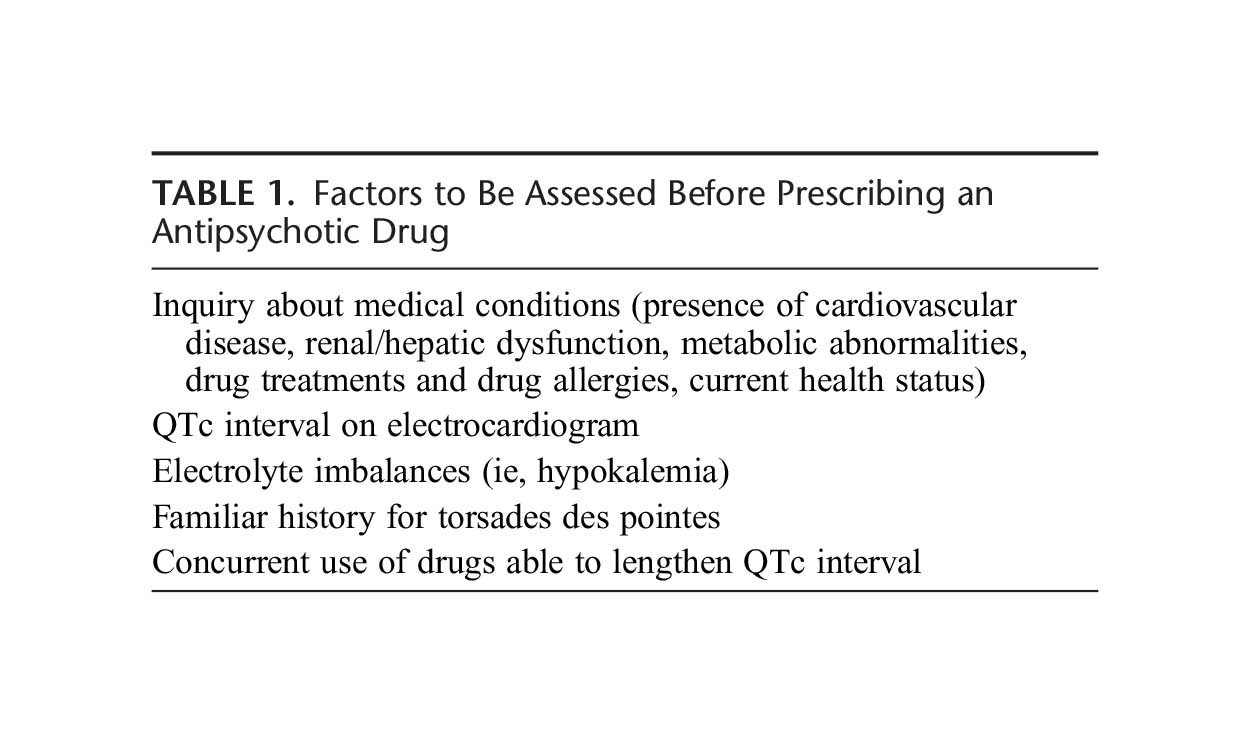

In a paper from February 2014, the authors review the the safety of the use of antipsychotics in elderly patients affected with dementia, restricting their analysis mainly to the last ten years. They concluded, “Use of antipsychotics in dementia needs a careful case-by-case assessment, together with the possible drug-drug, drug-disease, and drug-food interactions.” But interestingly they also say, “Treatment of behavioral disorders in dementia should initially consider no pharmacological means. Should this (sic) kind of approach be unsuccessful, medical doctors have to start drug treatment. Notwithstanding controversial data, antipsychotics are probably the best option for short-term treatment (6-12 weeks) of severe, persistent, and resistant aggression.” There are very clearly regulatory concerns of the safety of some antipsychotics, and yet the consensus appears to be they – whilst carrying substantial risk in some of very severe adverse effects – may also be of some benefit in some. It will be essential for the new National Dementia Strategy keeps up the only rapidly changing literature in this area, as do the clinical regulators.

Finally, in summary, I believe that there is enormous potential for England, and its workforce, to lead the way in dementia, in a way of interest to the rest of the world. I do think it needs to take account of the successes and problems with the five year strategy just coming to an end, with a three-pronged attack particularly on perception and identity, diagnosis and care. But, unsurprisingly, I believe that there are still a few gear-changes to be made culturally in the NHS, however it becomes delivered in the near future. There needs to be a clear idea of the needs of all stakeholders, of which the needs of persons with dementia, and those closest to them, must come top. There needs to be clear mechanisms for disseminating good practice, and leading on evidence-based developments in dementia wherever they come from in the world. And dementia policy should not be divorced from substantial developments from other areas of NHS England’s strategic mission: particularly in long-term conditions, and end-of-life care. This, again, would be the NHS delivering the right level of help for all those touched by dementia, from the point of diagnosis and well beyond.

Despite the sheer enormity of the task, I am actually quietly confident.