The eyes of the world, particularly those involved in research into the dementias like me, are currently fixed on Washington DC for the duration of #AAIC2015. This is the Alzheimer’s Association conference.

I suspect one of the big themes to emerge from this important conference will be to discuss innovative ways to get people involved in research in the first place. I think many of us have to work much harder on the message that people not living with dementia are essential for understanding dementia too.

In the old days, and I guess so now (provided ‘allowed for’ by local research ethics committees), people might be financially rewarded for their involvement in research.

With 850,000 people currently living with dementia in the UK, research into dementia is very likely to touch someone that someone knows at the very least.

But I’m sure we can rev up participation in research to an altogether different level. Instead of financial rewards, there is much intrinsic reward to be gained from taking part in research. The ‘points and levels’ are likely to trigger the ‘feel good factors’ of the brain, in the same way that primary rewards such as food are, I feel. I dare say there are neurology papers being peer-reviewed as we speak on the chemical dopamine release in the midbrain of successful participants in gasification.

Of course, I was delighted to see in a tweet Marc Wortmann leading a workshop; but equally importantly, perhaps, the air con appears to be functioning properly (in a subsequent tweet).

But smashing all records was the later news from Marc.

Don’t get me wrong. We have our own ‘internal difficulties’ in English policy: for example, the care costs cap delayed until 2020.

But the facts do speak for themselves. There are around 47 million people around the world living with dementia. It’s essential we have leaders from this community speaking up for what is needed from dementia research and service provision. Speaking personally, I am not at all impressed at their representation this year in the published timetable of #AAIC2015.

It is, however, important to be cheerful. Our friend and colleague, Hilary Doxford, has a seat at the table of the World Dementia Council, where Hilary’s views are definitely actively sought and acted upon. There’s no escaping that it is daunting task and ask for Hilary to represent 47 million of the world’s population.

Kate Swaffer, Co-Chair of the Dementia Alliance International or ‘DAI’, has been instrumental in changing atitudes around the world about dementia. Kate, herself living with a dementia, and also with a personal background of immense value, has been a relentless advocate, and some will rightly say, ‘crusader’ for the rights of people with dementia.

That is, because, we do in fact agree, surprising though that seems. Even in a brave new world where research has been able to provide a way of stabilising the main dementias in futures, there needs to be some sort of strategy, pharmacological or otherwise, to provide an environment to encourage the re-growth of appropriate nerve connections.

The idea that we might be able to identify those people who are at risk of developing dementia, say from their genetic profile, is not in fact an objectionable one. We have to be though realistic about the substantial contribution of the non-modifiable risk factors to the main dementias, particularly dementia of the Alzheimer type.

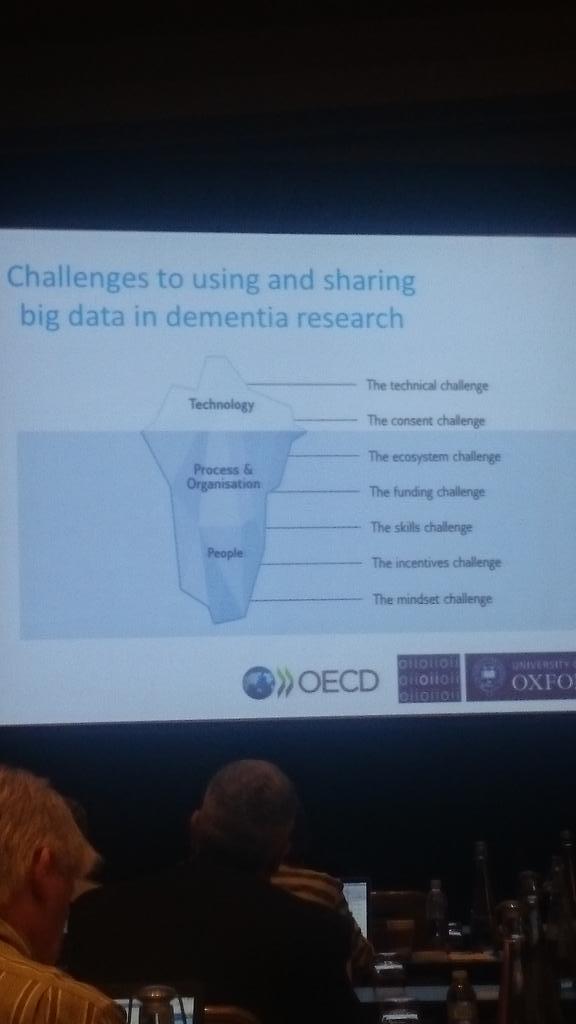

I don’t deny also there’s a rôle for elaborate Big Data analysis, but more doesn’t necessarily equal better. I was very pleased to see Martin Rossor, somebody I used for work briefly for more than a decade ago (and who was exceptional) and a Professor at UCL, present a ‘big picture’ look at Big Data.

I think Prof Rossor is indeed right when he says ‘Culture eats logic for breakfast’ even though it does sound like a punchy soundbite especially for Twitter – but like any innovation, the success is in the adoption and diffusion. And that is indeed where the ecosystem ‘kicks in’.

The UK clearly lags behind the US in research monies – but most of us here in the UK feels that UK research into dementias punches far above its weight, due to effective leadership and management of funds in part.

But if we are to aim for parity of esteem in service provision, where mental health is not seen as inferior to physical health, we should not see dementia as a second class citizen in research priorities either. Research in dementia lags far behind cancer in pure budgetary terms globally. Also it is convenient that dementia gets seen as a ‘social care issue’ rather than a medical issue for many, denying many citizens of monies which they need.

And let’s do have a frank discussion about diagnosis. I have a feeling we have an agenda here that many people at #AAIC2015 will not openly admit to. GPs in England are not given the resources including training often to make a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease confidently, arguably. It might be argued that GPs, who are incredibly hardworking and trained to a sophisticated level, do not feel as confident in diagnosing certain dementias, say primary progressive aphasia or diffuse lewy Body disease, as might be with appropriate backup.

I think it might be possible to have a ‘test’ for pre symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. But let us be clear about this – how are we going to roll out lumbar punctures for millions of people? Lumbar punctures, if not clinically contraindicated, are invasive tests.

How are we going to get round the false positives or false negatives?

And let us talk about the therapy for the dementias for a moment? I assume we will see from #AAIC2015 some discussion of risk mitigation, not simply for Chinese information firewalls in the flow of Big Data globally. Researchers, and the public demand too, a mature debate about the adverse effects of medications in trial at the moment; and also we need to have those presentations on the ability of those potential orphan drugs in crossing the blood brain barrier.

Orphan drugs for dementia have existed before.

One example is the a copper-binding chemical penicillamine for Wilson’s disease. I myself have spoken to the ‘doctorpreneur’ about this leap forward, Dr Walshe, at the Royal College of Physicians London in its building in St Andrew’s Place.

It won’t have escaped national governments that, even if they succeed in developing new orphan drugs for dementia, it can’t then get ‘blocked’ – in the UK, the NICE regulator could deem it cost ineffective.

“Living better” with dementia, I feel, is a reality, if we also invest in research here. This is not to undermine the brilliant work being done in “early detection”. We need to know about what conservative treatments in incontinence work, why music can seemingly unlock emotions in some people living with dementia, or why some people living with dementia experience a sudden emergence of new artistic talent?

All this research is essential, whether cure or care, or living better, for enhancing people’s quality of life, people living with dementia, as well as those closest to them. There’s no definitive right answer about the type of research which could or should be done.

But the research has to be ethical – it should respect autonomy, a wish to do good (beneficence), a wish not to do harm (non-maleficence), and justice (put in one way only, greatest good for the greatest number of people).

Quite often, I think we get obstructed about a fixation problem into the legality of research, important though that is from the harmonisation of research guidelines. These guidelines are critical, and followed Nuremberg.

The research has to be legal – but public policy demands are important too, as well as data protection, confidentiality and disclosure legalities across jurisdictions.

World research into dementia, whether cure or care, must be legal and ethical. I am proud of the UK’s involvement in world research in dementia.

We do need more money. I would say that wouldn’t I.