“Dementia Friends” is an initiative run by Public Health England, and delivered by the Alzheimer’s Society. In this series of blogpost, I take an independent look at each of the five core messages of “Dementia Friends” and I try to explain why they are extremely important for raising public awareness of the dementias.

When you see someone who is old, say above 65, they do not necessarily have dementia.

Dementia, caused by a disease of the brain, can affect any of the functions of the brain – such as movement, visual perception, memory or attention.

It’s felt that almost 40 percent of people over the age of 65 experience some form of memory loss.

When there is no underlying medical condition causing this memory loss, it is known as “age-associated memory impairment,” which is considered a part of the normal aging process.

But brain diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are completely different.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia worldwide.

The risk of getting dementia increases with age, but it is important to remember that the majority of older people do not get dementia. It is not a normal part of ageing.

Old age does not cause dementia but is a factor in developing the condition. The probability of an individual developing dementia increases with age, but not everyone will develop dementia in old age.

Dementia can happen to anybody, but it is more common after the age of 65 years.

Indeed, “young onset dementia” (YOD) plays out at a much younger age, anyway.

YOD, which most often plays itself out in the form of Alzheimer’s disease, is an abnormal neurological condition that is likely caused by a combination of factors.

YOD is increasingly recognised as an important clinical and social issue. This group of individuals have distinct needs for living well with dementia as far as possible.

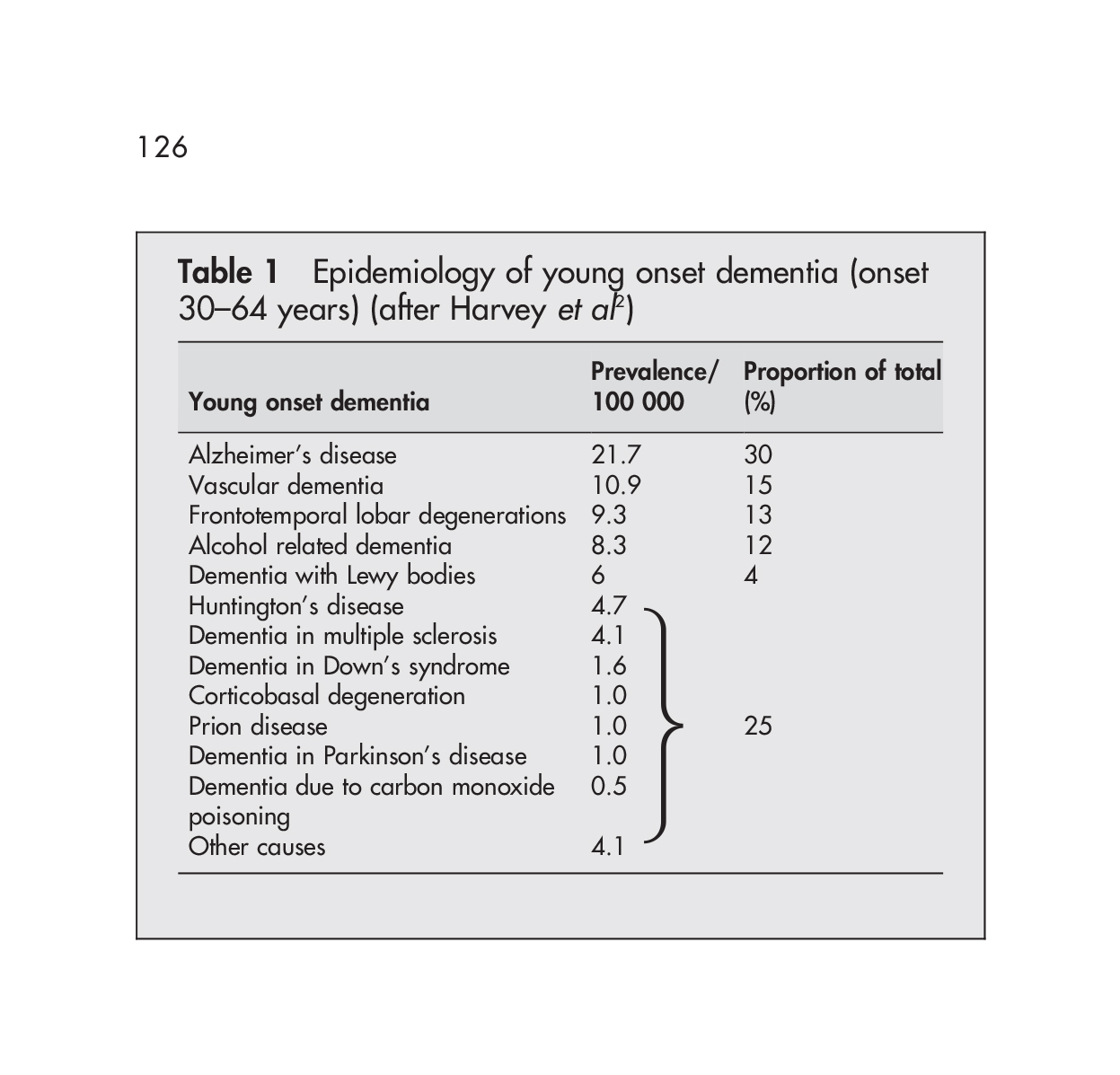

Young onset dementia (by EL Sampson, JD Warren and MN Rossor) [Postgrad Med J 2004;80:125–139. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.011171] cite a useful breakdown of the most common causes.

These causes are diseases, and produce a chronic, progressive course of dementia. The spectrum of diseases causes YOD bears some similarities and differences to that of diseases causing dementia in the older age group.

(from Sampson, Warren and Rossor, 2004)

Prevalence rates of young onset dementia have been estimated between 67 to 81 per 100 000 in the 45 to 65 year old age group.

A rare type of dementia, the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) was first reported in 1996; the youngest patient developed symptoms at 16 years of age (reviewed in Verity et al., 2000).

As described in the WHO factsheet 180, Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is a rare and fatal human neurodegenerative condition which is classified as a Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE), because of its ability to be transmitted and the characteristic spongy degeneration of the brain that it causes.

Its diagnosis does need to be in very specialist hands.

But, notwithstanding all that, is likely that the situation is likely to be very complicated.

The basal forebrain cholinergic complex including nucleus basalis of Meynert provides the mayor cholinergic projections to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.

Source here.

It’s thought that the hippocampus represents the story of facts or events (episodic memory), one of the bookcases in the “bookcase analogy” of the Dementia Friends initiative.

But it has latterly been acknowledged (Schliebs and Arendt, 2011) that he cholinergic neurones of this complex have been described to undergo moderate degenerative changes during aging, resulting in cholinergic hypo function that has been related to the progressing memory deficits with ageing.

References

Harvey RJ, Rossor MN, Skelton-Robinson M, et al. (1998) Young onset dementia: epidemiology, clinical symptoms, family burden, support and outcome, London: Dementia Research Group, 1998.

Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, et al. (2002) The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 58:1615–21.

Schliebs R, Arendt T. (2011) The cholinergic system in aging and neuronal degeneration, Behav Brain Res, Aug 10;221(2):555-63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.058. Epub 2010 Dec 9. Review.

Verity CM, Nicoll A, Will RG, Devereux G, Stellitano L. (2000) Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in UK children: a national surveillance study. Lancet. 2000 Oct 7;356(9237):1224-7.

WHO. (Revised February 2012) Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: factsheet no 180, available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs180/en/ [accessed 12 June 2014].