The setting for today’s #G8Dementia Summit was in Lancaster House, London.

Many thanks to Beth Britton, Ambassador for Alzheimer’s BRACE and campaigner, Anna Hepburn at the Department of Health, and Dr Peter Gordon, Consultant and expert in dementia, for helping understand, with the excellent livestream from the Department of Health, what challenges might be in store for global dementia policy in the near future.

My account is @dementia_2014

The final G8 Summit Communique is here.

The G8 Summit Declaration is here.

There’s a bit of a problem with global dementia policy.

The patients, carers, families, businesses, corporate investors, charities, media, academics (including researchers) politicians, all appear to have different opinions, depending on who you speak to.

Peter Dunlop, a man with dementia of Alzheimer type, received a standing ovation after his speech. He had explained his reactions on receiving a diagnosis, and how has tried to continue enjoying life. He had been a Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist.

Peter Dunlop: “I continue to enjoy life and fishing” – Moving testimony that a good life with #dementia is possible! #G8dementia

— Alzheimer Europe (@AlzheimerEurope) December 11, 2013

Peter Dunlop had a standing ovation from #G8dementia – NEVER underestimate the power of the lived experience of dementia

— Beth Britton (@bethyb1886) December 11, 2013

The people with dementia who appeared did indeed remind the audience, including Big Pharma, why they were there at all.

Trevor Jarvis talks about person-centered care and need for doctors to fully understand the disease. What an eloquent gentleman. #G8dementia

— Romina Oliverio (@RominaOliverio) December 11, 2013

And that there was more to life than medications:

AE Chair Heike von Lützau-Hohlbein highlights role of self-help movement and successful advocacy work #G8dementia

— Alzheimer Europe (@AlzheimerEurope) December 11, 2013

And this was sort-of touched on even by the Prime Minister:

‘Today is about three things: realism, determination and hope.’ @David_Cameron #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

And personhood was not completely lost on David Cameron MP:

‘… this is about allowing people to live well with dementia, and with dignity’ @David_Cameron #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

And this was indeed music to the ears of people like me, and countless of persons with dementia, their carers, friends and relatives, for example:

Cameron: It’s not just about finding a cure, it’s also about helping people with dementia to lead more fulfilling lives. #G8dementia

— DeNDRoN (@nihrdendron) December 11, 2013

Elephant in the room according to @marcwort is the number of people with #dementia in developing countries #G8dementia

— Alzheimer Europe (@AlzheimerEurope) December 11, 2013

And the carers were listening carefully too..!

listening for David Cameron to tell us some good news for those living with dementia now #G8dementia

— Dementia Skills (@Dementiaskills) December 11, 2013

There was some concern aired that the volunteers and charities would been seen as a valid alternative for a properly supported health and social care system. Whilst everyone agreed that ‘dementia friends’ and ‘dementia friendly communities’ were worthy causes, everyone also agreed that these should not replace actual care.

Please don’t defer the responsibility to volunteers and charities – health and social care need to step up #G8dementia #DAACC2A

— DAA Carers Action (@DAAcarers) December 11, 2013

Part of the aim of today was to foster of culture of diminishing stigma. And yet the media had been full of words such as ‘cruel disease’, ‘robs you of your mind’, ‘horrific’. So the politicians seem conflicted between this utter armageddon and wishing to destigmatise dementia, with generally pitiful results.

Some of the language in the last 24 hours has indeed been truly diabolical. I took a break to watch the main news item on the BBC, and Fergus Walsh was heading up the main item on dementia with extremely terrifying language.

#G8dementia I was going to keep track of how many times the word “Fight” was used today. I have long since lost count! #militarymetaphors

— Peter Gordon (@PeterDLROW) December 11, 2013

But the Summit kept on reverting to the ‘real world’, pretty regularly though.

A pervasive theme, brought up by many health ministers and other interested parties, was how dementia carers themselves needed supported. Dr Margaret Chan even later in the day spoke about a new online resource for carers, which would be fantastic.

“Dementia carers also need our support.” Dr Chan @WHO #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

‘We’re going to develop an online resource to help carers.” Dr Margaret Chan @WHO #G8dementia This is indeed brilliant news.

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

An aspect of why this situation had arisen was not really explained. Prof Martin Rossor, Honorary Consultant for the Dementia and Cognitive Disorders unit at Queen Square, described the dementia issue as ‘a wicked problem’ on the BBC “You and Yours”. However, Dr Margaret Chan from WHO was much more blunt.

“This is yet another case of market failure.” Dr Margaret Chan @WHO #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

Big Pharma had failed to ‘come up with the goods’, despite decades of trying.

Dr Chan: In terms of a cure (for #dementia), or even treatments that can modify the disorder or slow its progression, we are empty-handed

— WHO (@WHO) December 11, 2013

But few speakers were in any doubt about the societal impact of dementia, though much of the media resorted to scare tactics as usual in their messaging.

London-G8HealthMinisters on dementia. One of the most important challenges for ageing societies.Huge human,social and economic impact.#OECD

— Yves Leterme (@YLeterme) December 10, 2013

The speakers on the whole did not wish to discuss how care for people could be reconfigured. The disconnect between the health and social care systems is clearly a concern in English policy. And indeed this was even raised.

Integrated approach for the delivery of services bridging health and social care is needed, says @yleterme #G8dementia

— Alzheimer Europe (@AlzheimerEurope) December 11, 2013

All was not lost regarding wellbeing.

Hazel Blears, Labour MP for Salford, explained how her mother was living with dementia, so it was vital that policy should do everything it could do to help people live with dementia.

“We need to find the evidence for non-pharmacological interventions as well.” @HazelBlearsMP #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

I met the Salford Institute for Dementia, a brand new Twitter account, for the first time this afternoon, which was in fact one of the highlights of my day.

Salford Institute for Dementia launched to use research to improve the lives of people with dementia #G8dementia http://t.co/BgDw3X9Xw9

— Inst for Dementia (@InstforDementia) December 11, 2013

Although not pole position compared to ‘cures’ and ‘disease modifying drugs’, it was clear that the #G8summit were keen to support assistive technology, telecare and telemedicine. This could be in part due to the generous research grants from various jurisdictions for innovation, or it could be a genuine drive to improve the wellbeing of persons living with dementia.

‘Homecare is arguably one of the best means of care because of quality of life – we should all think of innovative ways to keep ppl at home’

— Anna Hepburn (@AnnaHepburnDH) December 11, 2013

At just before lunchtime, I suddenly “twigged it”.

I must admit I was angry at myself for having been “slow on the uptake”.

I now understand what this ‘data sharing’ drive is about. It’s for DNA genomic collaboration to develop personalised treatment. #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

As it was, the discussion appeared to swing periodically between two ends of an extreme during the course of the day. At one end, the discussion was about ‘big data’ and ‘open data’ sharing.

Vivienne Parry , then said how she preferred the term ‘safe data’ to ‘open data’, but Twitter was at that point awash with queries as to whether a rose by any other name would smell as sweet?

@vivienneparry has hit the nail on the head; ‘unsafe’ data sharing could be perceived as reducing risk for corporate investors. #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

People conceded the need for persons and patients voluntarily to contribute to these data sets, and for international organisations such as WHO to attempt to formulate standardised harmonised templates for these data. At the other end, people were very keen to talk about genetic information, presumably DNA, being the subject of DNA genomics data scrutiny at a personal level.

Also, the discussion itself swung from personal tales (such as Beth Britton’s) to a discussion of looking at societal information as to what sorts of data clusters might show ‘susceptibility’ in their genetic information decades before the onset of clinical dementia. Big data, like 3D printers, has been identified as ‘the next big thing’ by corporates, and it’s no wonder really that big data should of interest to big Pharma corporates.

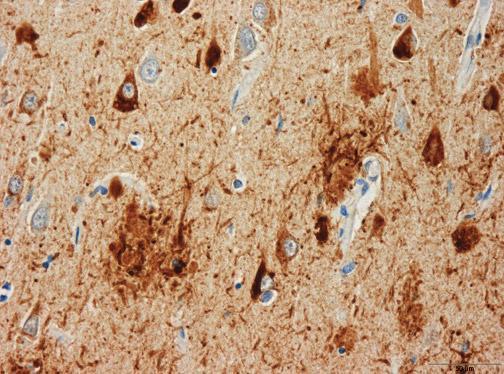

Having failed spectacularly to have produced a cure or disease-modifying drugs across a number of decades, Pharma are left with two avenues. One is that they look at the individual response to therapy of drugs at a single case level using radio-active binding studies (radio-ligand binding studies), and monitor any slowing of build-up of abnormal protein in the brain as a response to treatment. How much this actually benefits the patient is another thing.

Or Big Pharma can build up huge databases across a number of continents with patient data. Researchers consider this to be in the public interest, but patients are clearly concerned about the data privacy implications.

Here, it was clear that Big Pharma could form powerful allies with the charities (which also acted as patient groups):

“Data sharing is absolutely essential to make the advances needed across the world.” Harry Johns, Alzheimer’s Association #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

And of course this agenda was very much helped by Sir Mark Walport being so enthusiastic about data sharing. Having been at the Wellcome Trust, his views on data sharing were already well known though.

“There are concerns about ‘Big Data’ around the world.” Sir Mark Walport CSO #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

If it were that regulators could allow data sharing more easily, justified presumably on public policy grounds such that freedom of information was more important than data protection according to the legal doctrine of proportionality, this plan could then considerably less risky for corporate investors wishing to invest in Big Pharma.

Andrea Ponti from JP Morgan gave this extremely interesting perspective, which is interesting given the well known phenomena of ‘corporate capture’ of health policy, and ‘rent seeking behaviours’ of corporates.

The G8 have a great opportunity to altering the risk and return ratios, important for investors.” Andrea Ponti @jpmorganfunds #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

It has been argued that waiting for valid consent from the patients would take too long, so presumed consent is more of a practical option. However, this ethically is an extremely tricky argument. The Pharma representatives were very keen to emphasise the ‘free flow’ of data, and the need to ‘harmonise regulation'; but they will be aware that this will requiring relaxing of the laws of more than one country.

And so, during the course of the day, the agenda of Big Pharma became clear. They intended to be tough on the lack of cure for dementia, and tough on the causes of that cure. Some might say, that, as certain anti-dementia drugs come to the end of their patents (and evergreening is not an option), they have suddenly converged on this idea to tackle dementia, as it is a source of profitability to enhance shareholder dividend. They now need new business models to make it succeed (and various charities and research programmes which benefit from this corporate citizenry might be able to make it work too.)

“We have introduced approaches which encourage personalisation and individualisation of care.” Madame Marisol Touraine #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

But during the course of the day those ‘pesky’ tweets about person-centred care kept on coming…

As #G8Dementia summit about to start – see the person not the diagnosis with @SCIE_socialcare award winning film http://t.co/PJ58m6xWB9

— Andrea Sutcliffe (@Crouchendtiger7) December 11, 2013

Some of the tales were truly heart-breaking.

“I lost friends. Well I say friends. If they can’t cope with a diagnosis of dementia, they’re not really friends.” @BethyB1886 #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

But I was happy because Beth was happy at the reception of her film. She is so utterly passionate, and totally authentic, about the importance of her father who had dementia. It was a privilege for us to see how well the film had been received by all there at the #G8summit.

Our montage film, featuring people with dementia & carers (inc me), well received at #G8dementia

— Beth Britton (@bethyb1886) December 11, 2013

And those pesky tweets kept on coming…!

Watch our award winning #SocialCareTV film ‘Getting to know the person with #dementia‘: http://t.co/tivbpYkb8Z

— SCIE (@SCIE_socialcare) December 11, 2013

But indeed there was a lot to be positive about, as research monies if well spent could provide a cure or disease-modifying drugs. Big Pharma and the researchers know that they are not only trying to tackle the big one, the dementia of the Alzheimer type, but also other types such as the vascular dementias, frontotemporal dementias and diffuse Lewy body disease.

EU announces Horizon 2020 call dementia & neurodegenerative disease in 2014/2015 €1.2 billion #G8dementia @isgtw @martinrossor

— DeNDRoN (@nihrdendron) December 11, 2013

Beth’s input today was invaluable.

“I would really like to make a plea, on behalf of the delegates, for non-pharmacological interventions. Thank you.” @BethyB1886 #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

And Dr Peter Gordon loved it!

@bethyb1886 and @HazelBlearsMP well said, both of you. We need balance in our approach. Your voices matter so much #foryourfolk

— Peter Gordon (@PeterDLROW) December 11, 2013

But the best comment of the day must certainly go to Dr Margaret Chan, a V sign to those obsessed with Big Data spreadsheets and molecular biologists looking at their Petri dishes:

‘We’re going to develop person-centred care, not talk about people as collections of organs or diseases’ Dr Margaret Chan @WHO #G8dementia

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) December 11, 2013

In summary…

It smelt like a corporate agenda.

It looked like a corporate agenda.

It sounded like a corporate agenda.

And guess what?

All the ingredients of ‘corporate capture’ were in attendance: big data, personalised medicine, genomics, data sharing. They’d have managed a full house had the world leaders found a use for 3D printers in all of this.

Related articles

- The G8 Dementia Summit cannot just be about “Pharma-friendly communities” (livingwelldementia.org)

- All stick and no carrot? How much diagnosis, but how much actual care, of dementia? (livingwelldementia.org)

- The #G8Dementia Summit – hopefully a chance for real campaigners, not an international trade fair (livingwelldementia.org)

- Dementia cure ‘within our grasp’, says David Cameron (standard.co.uk)