In a rather strange Stakhanovite way, certain health magazines are strangely obsessed with the fetish of the ‘top 100′. I am as such not a great advocate of, “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.” immortalised by Chapter 3 of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but as someone who has devoted all of his entire life to dementia academia I do find somewhat curious (to put it politely) the judgments of those outside the dementia field about who are most influential to other people outside the academic dementia field, in their “world of dementia”. However, corporates need ‘symbols’ of their ‘success’ to attract inward attention and investment, so I’ll simply leave them to their own pathetic whims.

The issue of who “influences” a given network is currently of huge interest in modern ‘actor network theory’ (ANT). ANT was first developed at the Centre de Sociologie de l’Innovation of the École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris in the early 1980s by staff and visitors. Network thinking has contributed a number of important insights about social power. Perhaps most importantly, the network approach emphasises that power is inherently relational. An individual does not have power in the abstract, they have power because they can dominate others.

Network analysts often describe the way that an “actor” is embedded in a relational network as imposing constraints on the actor, and offering the actor opportunities. Actors that face fewer constraints, and have more opportunities than others are in “favourable structural positions”. Having a favoured position means that an actor may extract better bargains in exchanges, have greater influence, and that the actor will be a focus for deference and attention from those in less favoured positions. However, a key deference is that the people mentioned below do not consider themselves as requiring deference or attention. Their devotion to the living with the dementias is crystal clear. There can of course be “inhibitors”. We all know who they are: they actively stifle the activities of some members of the community.

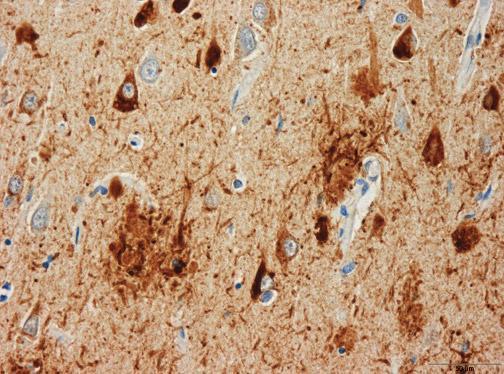

There are many laboratories around the world which publish widely in the world on cognitive and behavioural neurology: how people think, and the brain processes involved. Of the off top of my head, I can think of Prof Bruce Miller at the University of California and San Francisco, Prof Martin Rossor at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and University of London (UK), Prof Facundo Manes at Favorolo Hospital, Argentina, Prof David Neary at the University of Manchester (UK), and Prof John Hodges of NeuRA, Australia.

There are of course people in fields to do with living well, for example defining wellbeing, measuring wellbeing, assistive technology, ambient assisted living, design of the home, design of the ward, and design of the built environment. Research in all these areas in English dementia policy is currently extremely important. I would go so far as to say that the people successfully working in, and publishing on, these areas around the world are much more important than the health ministers and corporate representatives who spoke at the ‘G8 dementia’ conference last week.

One person who does deserve a special mention though, even though all must have possibly have prizes, is Beth Britton. Beth’s interview captured attention at last week’s #G8dementia, and rightly so. Beth’s father had vascular dementia for 19 years. It began when Beth was around 12 years old, and would go on to dominate Beth’s life in her teens and twenties. Her father, whom she clearly adores, went for ten years without a diagnosis and he then spent none years in three different care homes. He passed away in April 2012, aged 85.

Norman McNamara from Devon was diagnosed with dementia a few years ago when he was just 50. After his diagnosis, Norman, from Torquay, began blogging online about his experiences and during a phone call with a friend he had the idea of organising the first Dementia Awareness Day on 17 September 2011. Norman particularly is really helpful in offering insights about what it’s like to ‘live with dementia’. In his recent blogpost, for example, he talks about how he doesn’t wish to be seen as being on some ‘journey’. He talks poignantly about how he is ‘living with’ dementia, not ‘dying from’ dementia, stating correctly that we are all in fact dying if one took this approach.

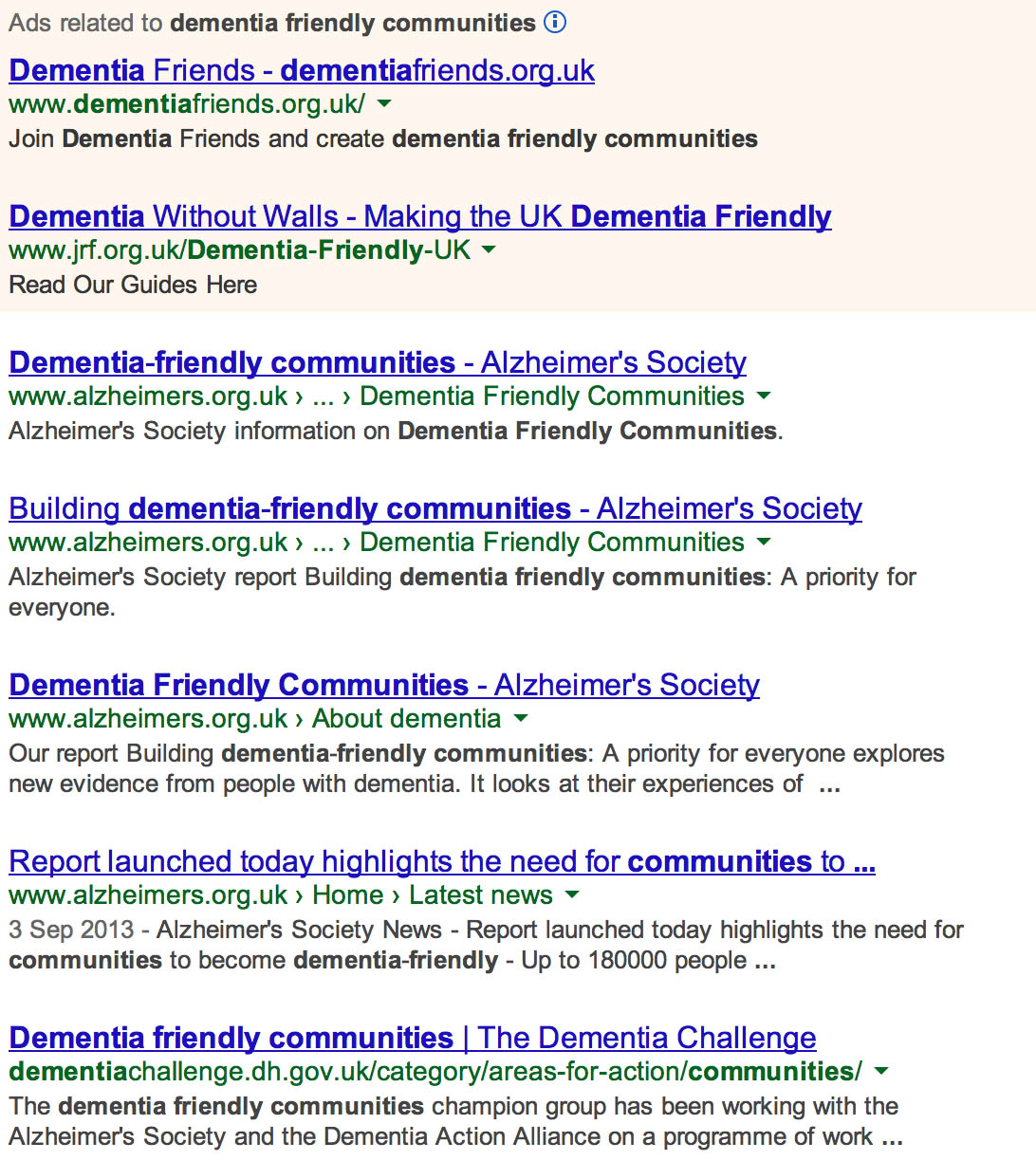

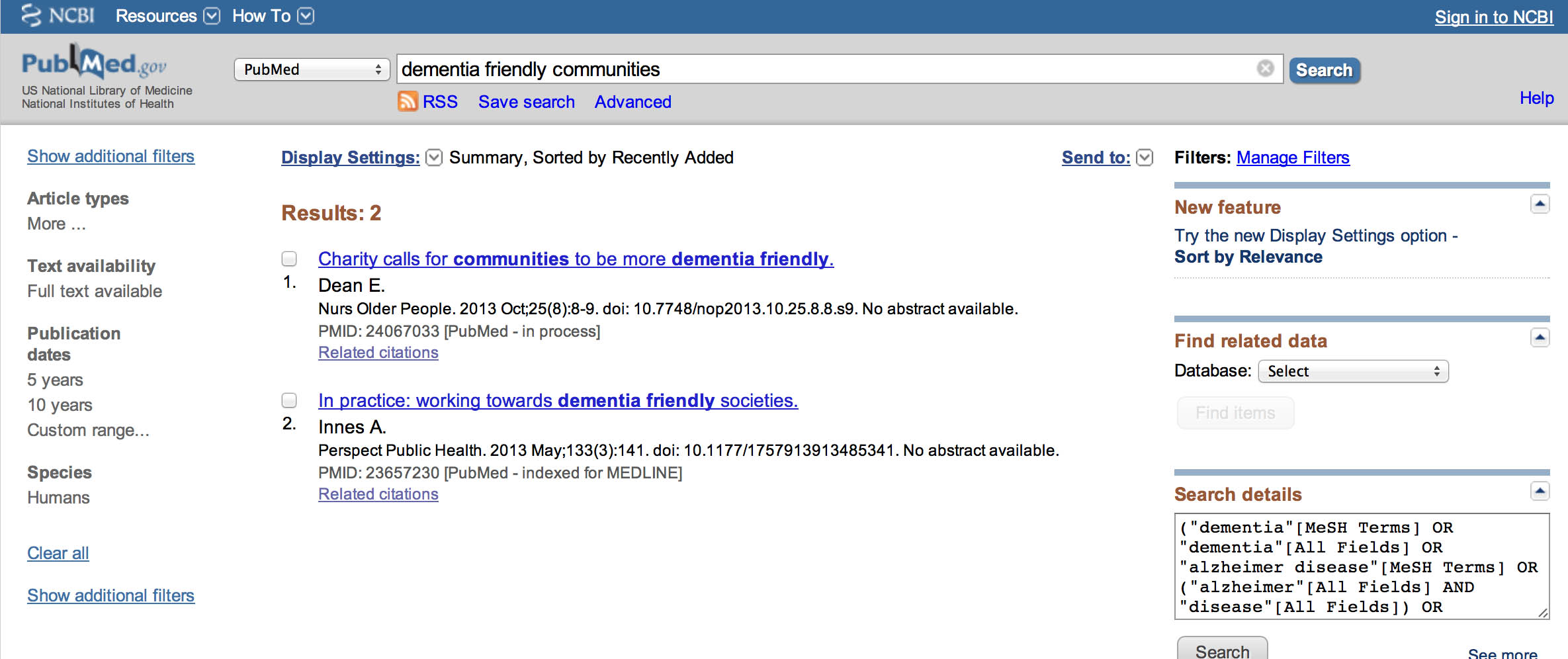

Kim Pennock, from Thornton-le-Dale, gave up her part-time job at Beck Isle Museum to help care for her mother who has the dementia of the Alzheimer type. Kim has become one of only 50 worldwide ambassadors for a pioneering new project to make communities safer for people with dementia. When her mother was first diagnosed, Kim said the family found it almost impossible to find the information and help they needed. Conversely, Lee set up the incredible ‘Dementia Challengers’ website to help people with dementia and the carers the right info they need to help them to live well.

In Australia, Kate Swaffer is committed to meaningful dialogue with a wide range of stakeholders about the critical issues impacting a person living with a diagnosis of dementia and their loved ones. When a person with dementia ‘comes out’ about their diagnosis, and openly admits they are living with the symptoms of, and diagnosis of dementia, there are a number of reactions and responses. Kate is one of the world’s most powerful advocates for dementia and the elderly, living well with a diagnosis of dementia; and she describes herself on Twitter (@KateSwaffer) as an “author, poet, blogger, and always trying to be a nice person”.

Back in the UK, Fiona Phillips speaks directly from her first hand experience as her mother had Alzheimer’s until her death in May 2006 and her father, who was diagnosed with the disease shortly afterwards, died in February 2012. In January 2009, Fiona presented Mum, Dad, Alzheimer’s and Me, an incredibly moving “Dispatches” documentary on Channel 4, featuring Fiona talking candidly about her struggles caring for both her parents during their respective illnesses and investigating the difficulties faced by people with the dementia of the Alzheimer type, and their families to get adequate care and support. Fiona has written a book “Before I Forget”, about her relationship with her parents and their dementia.

There are certain people who do understand particular areas of dementia policy and education. Lucy Jane Marsters is one such example, being a specialist nurse. Gill Phillips has also been pivotal in raising awarneness, generally, of the significant to personal-centred approaches in questioning quite deeply entrenched assumptions. There are also some brilliant people in innovations, such as Mike Clark, Prof Andrew Sixsmith and Prof Roger Orpwood in telemedicine and telehealth. Activities and healthy living communities are also extremely important; despite challenges in funding, like many in the dementia world, Simona Florio has been utterly resolute in supporting members of the excellent Healthy Living Club in Stockwell.

For years, magnificent Scot Tommy Whitelaw travelled the world running global merchandising operations for the Spice Girls, Kylie and U2. However, over the past few years he had become a fulltime carer my late mum, Joan, who had vascular dementia. His motivation as a carer came from the love he had for his own mum, and his experience has shown me just how tough it is to live with dementia and how many struggles it can bring. For the last year, he has been collecting carer’s life stories to raise awareness. Tommy is now working on The Dementia Carers Voices project with the Health and Social Care Alliance which will build on my ‘Tommy on Tour’ campaign by engaging with carers, collecting their life stories and raise awareness amongst health and social care professionals on both dementia and caring.

Caring for someone with dementia clearly infuses some with an incredible passion for the subject which you simply is hard to match. Sally Marciano has talked openly about supporting her mum supporting her father who later died of a dementia. She has talked openly about how the system didn’t work properly, but is very constructive about raising awareness and educational skills in the healthcare sector.

In March 2013, filmmakers and scientists come together at an event to increase the public understanding of dementia. A series of short films about dementia was presented by James Murray-White, will precede a discussion with researchers from the University of Bristol and other institutions supported by “Alzheimers BRACE”, a local charity that funds research into Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. James’ activities include being a freelance writer, journalist, reviewer, and filmmaker. James was in fact featured in last week’s #G8dementia media coverage.

Sarah Reed’s mother had Alzheimer’s disease for ten years. As a result of this, she became passionate about the quality of life of older people, especially those with dementia. She left a design career to found “Many Happy Returns” in order to innovate, research and develop evidence-based products to connect young and old, especially those with dementia, more meaningfully. Her goal has to change the experience of dementia for those who have it for the better, by persuading care organisations and carers everywhere that good care counts for nothing without good communication – and then helping them to deliver it.

And of course there are some brilliant influencers in the world of medicine who don’t simply regurgitate the copy fed to them. Dr Peter Gordon has produced a number of original films and articles about the ethics of the diagnosis, particularly the need for a ‘timely’ rather ‘early’ diagnosis, and potential conflicts of interest between the medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry. Dr Martin Brunet has likewise become massively influential in articulating the debate, especially, from the medical profession’s perspective of a policy ‘target’ to increase diagnosis rates. While Martin’s work is not easy, his perspective and substantial experience as a GP is invaluable, particularly in redressing other people’s motives which can too easily be too motivated by surplus and profit.

And, of course, a top influencer, even though ‘all shall have prizes’, is Prof Alistair Burns. Alistair is the clinical lead for dementia in England, and has a highly influential position in NHS England. Alistair clearly has a number of different stakeholders with which he needs to have a fair legitimate discussion about English policy. He has nonetheless steered the policy through rather turbulent times. As a senior academic and person within higher education, and someone who clearly has a very ‘human perspective’ too, his contribution to English dementia policy has been much valued and much appreciated.

Actually, I’m being totally ingenious. Most of us are actually one big happy family in the network I’m in. We have our disagreements, but we value each other. We don’t inhibit one another (which is what can go wrong with networks). For a list of #dementiachallengers, please go to the list in the top right corner of this blog. You’ll see for example Charmaine Hardy, who cares for, and adores, her husband who has a very rare form of dementia called primary progressive aphasia. Though having a well deserved break for once in Norway, for once, you can catch her on Twitter!