Assessing risk is a critical part of English dementia policy at all levels. I again found myself talking about risk as I saw responses to World Alzheimer’s Day which was yesterday on September 22nd 2015.

I don’t especially like the term ‘wandering’ for people with dementia. This term, like ‘challenging behaviours’ has become seemingly legitimised through the hundreds of papers on it in the scientific press, and the grants no doubt equivalent to hundreds of thousands of dollars probably. I think the term, intentionally or not, attributes blame. And as I moot in the tweet below, this is potentially a problem, especially one considers that a dementia charity should not ideally be fundraising out of sheer fear.

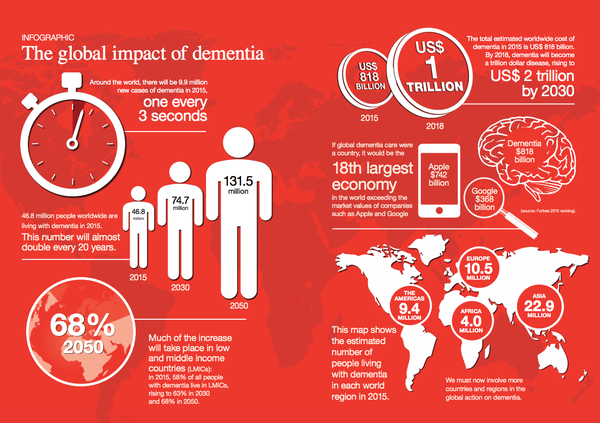

Don’t get me wrong. I think charities have an incredibly important part to play, and they do, in educating people about dementia; and generally ‘raising awareness’ howeverso defined. Take for example this helpful tweet from the Alzheimer’s Disease International containing a relevant infographic about the scale of the dementia epidemiology.

I had a hunch that something was very awry about yesterday when my colleague Simon Denegri tweeted something which caught my eye. Let me introduce you to Simon. He’s Chair, INVOLVE, NIHR National Director for Patients and the Public in Research, and, importantly, a nice guy.

The tweet, and the main subject of the research, is pretty self explanatory in fact.

The point Simon raises is worth thinking about, I feel. Is updating the epidemiology of dementia every year, nay every month, or even every week, an effective way of genuinely raising public awareness – or is it rather a lazy way to campaign on it? Obviously, playing devil’s advocate, one should argue that this main issue should be raised until something happens, but with a cure for dementia a long way distant it seems that this option is not likely.

So how about offering some solution instead? In other words, having scoped the problem, why not offer hope instead of fear through the huge volume of research in improving quality of life for people living with dementia and carers. Here’s the thing: there are 850,000 people living with dementia at the moment currently, and there’s got to be something in it for them with all this coverage.

I call fixating on the ‘tsunami’, ‘time bomb’ or ‘tidal wave’ “the shock doctrine” to make you want to dig into your deep pockets, to make you donate to a dementia charity. BUT – with social care funding on its knees, having not been ringfenced since 2010 – is this actually a luxurious response to a rather serious immediate problem? Long before #DementiaWords ‘got sexy’, I presented my poster (PO124) on the hyperbolic language used in the G8dementia proceedings, in the Alzheimer Europe 2014 conference.

Here’s the rub.

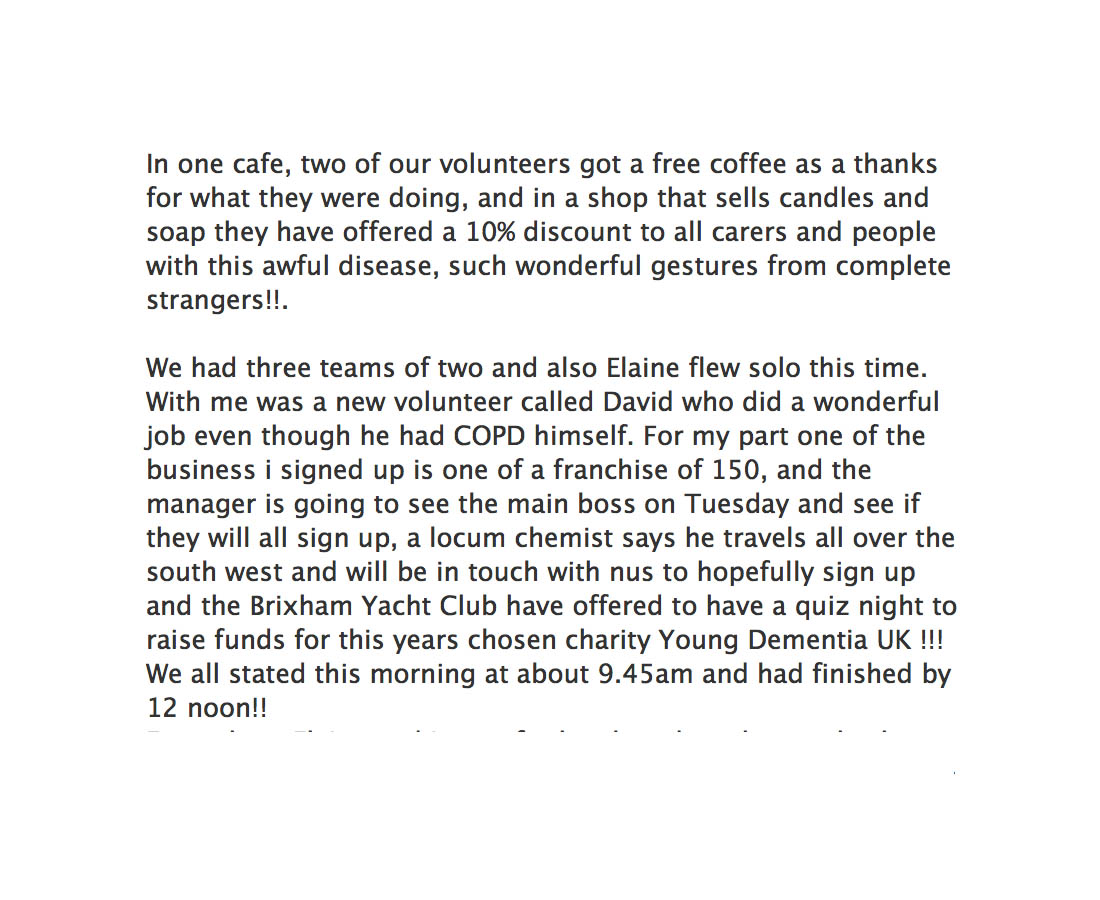

Jeremy Hughes and the Alzheimer’s Society have been hugely successful with the ‘Dementia Friends’ campaign, which has seen a roll-out of information sessions on the basics of dementia for the whole country. Yesterday was a good opportunity to talk about that.

But meanwhile Alzheimer’s Research UK, which indeed does formidable work for the research infrastructure on dementias in the UK, rolled out this in a blogpost yesterday. The phraseology of the remark, “At Alzheimer’s Research UK, our hope is for a different kind of future, one where future generations will be free of this life-shattering condition”, is the opposite to one of the central messages of Dementia Friends, that ‘it is possible to live well with dementia’.

I don’t, of course, want to downplay the huge significance of the disclosure of the diagnosis of dementia as a life event for all those involved, not least the direct recipient of that diagnosis.

Sadly, we’ve been here before. All of these came to the fore when Richard Taylor PhD, one of the founding members of Dementia Alliance International, (DAI), pleaded, “Stop using stigma to raise money for us”, in the Alzheimer’s Disease Conference in 2014 in Puerto Rico. Actually, the DAI, a group run by people living with dementia, has been working with Alzheimer’s Disease International to make things much better, in no small part at all due to the gigantic efforts of its current Chair Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer).

All of this leads to me wonder who exactly is protecting whom? I wouldn’t go so far as to say that the public needs protecting from large dementia charities, but the sway they hold on policy is not inconsiderable; whether this is on the cure v care resource allocation in dementia, or whether there should be specialist nurses as well as dementia advisors (as I argued this year both in the ADI and Alzheimer Europe conferences).

There’s no doubt, as regards safeguarding issues, that people with dementia need to protected from risk where it is proportionate to do so. As I have long argued, you need to embrace risk to live well with dementia. But it is worth thinking about on whose part we are negotiating risk? Damian Murphy’s excellent blogpost yesterday emphasises how we cannot necessarily assume that carers and persons with dementia have the same (or even similar) viewpoints: this is directly relevant, say, on whether a person with dementia with a carer gets a GPS tracking device? (I duly anticipate and expect Damian’s contribution here, by the way, to be seminal one, by the way.)

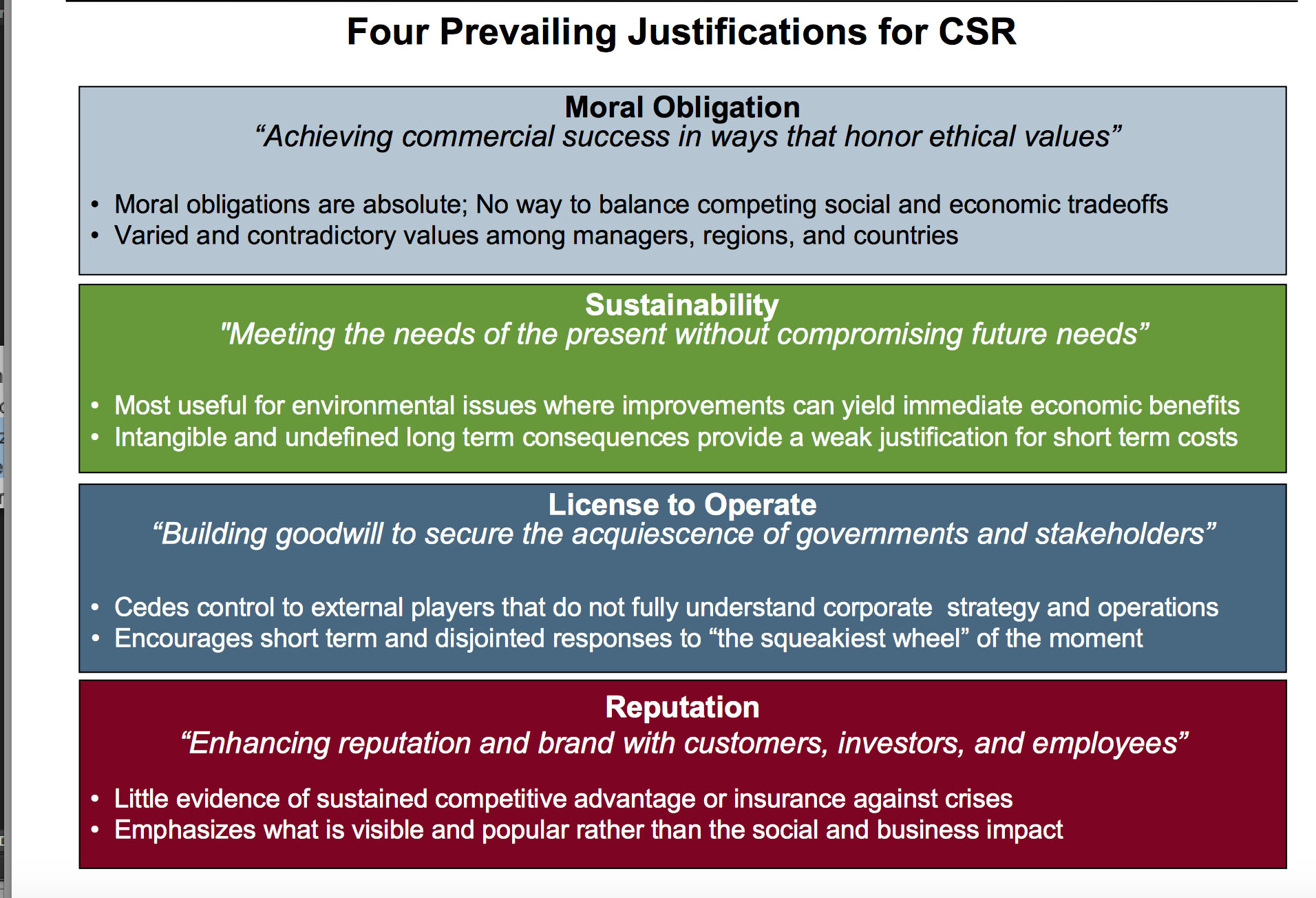

A long time ago when I was reading some of the management literature, I was really impressed by a paper to which Prof Michael Porter contributed on strategy and society (co-author Mark Kramer) in the Harvard Business Review.

Mark in a slide once summarised four crucial tenets of observing this re-articulated corporate social responsibility thus.

I, for one, would like to see all campaigning done by the dementia charities seen through this prism; and also bearing in mind the clinical, if not societal, question cui bono?