In the G8dementia, particularly by large corporate-like charities, dementia has been compared to the cancers. Whilst there are many problems with this comparison medically, the aim is for research and service expectations to be met in dementia on an equal footing to those for cancer. There are different types of dementia and different types of cancer, and there is, according to NICE, no current treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, the most common type of dementia globally, which slows the progression of disease. The aim however is undeniably a laudable one. In terms of service provision, the hope is that medical conditions can be detected early (and not at the last minute), and over time care and support can be introduced and implemented in a non-panicky way. The low hanging fruit is for providers at the front end of the service to game the NHS QOF/CQUIN system to design ‘innovative’ packages which might diagnose certain forms of dementia, such as the profound short term learning and memory problems in early Alzheimer’s disease. But getting out of this ‘quick fix’ mentality is going to be essential for the long-term sustainability of dementia services in England I feel. I believe strongly that clinical nursing specialists would not just be a big help here: they are indeed vital. England will really benefit from senior people in dementia taking the bull by the horns, in keeping with a refreshing approach to the long term conditions (LTCs) in general, as helpfully described by the King’s Fund in this policy pamphlet from 2010.

But I have now spoken to two very senior specialist clinical nurses in the NHS. One who has been at the heart of policy for nursing in the last few years, and the other one who has been at the heart of one of the top clinical firms in cognitive disorders here in London for a few decades. They both said exactly the same thing to me: “What we’re fed up about is the fast turnover of services and personnel within them. It’s difficult to find the same person twice. And we’ve got too many people signposting services, and not enough people providing frontline care.” There is undoubtedly a rôle for a trained person who can help to navigate a person with dementia and his or her caregivers around a profoundly complicated system. I’ve heard that “dementia advisers” can be brilliant at a local level, but can easily come to the limits of the skills they can sometimes offer. The system is too bitty and disorganised at the moment; and persons with dementia (some of whom who become ‘experts by experience) and caregivers have a key rôle in optimising design of service and revision provision for dementia in the future.

As a person progresses along “a dementia journey”, a term itself which attracts some considerable criticism, his or her own needs will tend to change from living well independently with dementia to benefiting from increasing levels of support, and then increasing levels of care. Two big events could happen along this ‘journey': the loss of decision-making ability (mental capacity), and the preference to move into a residential home of sorts. The timing of these events can be very hard for people with dementia or their caregivers to predict. There can also be worsening problems in communication between people with dementia and those closest to them, including friends and family. If a person living with dementia needs suddenly to enter hospital as a ‘crisis’ at 4 in the morning, he or she might be blue-lighted in with an infected full bladder causing a deterioration in cognition and behaviour, without a care plan in sight.

Diagnosing dementia is clearly not enough, but a timely diagnosis can be helpful. Professional physicians, nurses and other staff will always consider their professional including moral obligations in how likely the diagnosis is, how much a person wants the diagnosis, and how much to investigate a possible diagnosis. And there are too many cases of the possible diagnosis being given in a busy clinic, often summarised as an ‘information pack'; at worst, some people lost to the system for years before anything new happens.

It is likely that England will develop ‘integrated care organisations’. This does not involve building new departments and new buildings, but is a shift in organisational mindset such that GPs with a specialist skill in dementia service provision can work alongside other trained professionals and caregivers, with the person with dementia. This ‘working together’ is nothing new. It has been brilliantly described in the policy work of the Carers’ Trust in their recent documents ‘A triangle of care’ and ‘A road less rocky’. Caregiving can be intensely rewarding, but can also be hard work with caregivers having specific needs of their own. Caregivers will also be at the very heart of any personalised care plans. A professional who might be involved is a speech and language therapist. There is a national shortage of experienced speech and language therapists which is a tragedy as some forms of dementia, for example logopenic primary progressive aphasia, might be characterised by substantial problems in language in the relative absence of problems in domains such as episodic memory.

As a dementia progresses, a clinical psychologist will be in a brilliant position to work out why a person might have practical problems in real life due to identifiable problems in thinking, such as planning. A planning problem might be manifest as a person being able to make a cup of tea, or to organise a planning trip. Or, a clinical psychologist will be able to tell a team that what appeared to be an optician-related matter with eyesight is in fact a higher order perceptual problem as found in the rarer posterior cortical atrophy type of dementia (where memory can be normal early on.) An occupational therapist can use his or her own expertise here. Whichever way you look at it, dementia service provision needs are likely to be met from clinical teams who are an integral part of the ‘dementia friendly community’, who have been somewhat disenfranchised out of the conversation so far compared to high-street customer-facing corporates. Professionals, even in the context of meeting their regulatory obligations, have, I feel, a massive rôle to play in providing personal communities even if they do not assume legal duty of care. It is now known that activities can not only enhance wellbeing, but can also possibly slow the rate of progression (although the evidence base for this finding is not particularly robust yet.)

In the last few years, since the Health and Social Care Act (2012), was introduced, there has been massive turmoil in the National Health Service (NHS), leading at worst to fragmented services resulting from slick pitches from well funded private providers unable to deliver on their contracts. And yet if the NHS were given the correct management and leadership skills, they could be at the heart of providing world class care in dementia. Economies of scale, with free knowledge transfer, can be advantages of large organisations. Given that there are a million people in the next few years living with dementia, the NHS should be planning ahead for this, not just counting the number of new diagnoses as a manifestation of glorified bean-counting. The drive to diagnosis has been a classic example of where the target has become the means to an end in itself.

Earlier this year in July 2014, it was reported that cancer care in the NHS could be privatised for the first time in the health service’s biggest ever outsourcing of services worth over £1.2bn. The four CCGs were involved, which care for 767,000 patients, are also seeking bidders for a separate £535m contract to provide end-of-life care. Whoever wins the cancer contract will then have to “transform the provision of cancer care in Staffordshire and Stoke”. The prime provider will “manage all the services along existing cancer care pathways” for the first two years after which “the provider will assume responsibility for the provision of cancer care, in expectation of streamlining the service model”, according to details posted by the CCGs on the main NHS procurement website.

Macmillan Cancer Support were able to bring clinical nursing specialists (CNS) to the table: the “Macmillan nurses”. This robust model, which had proper financial backing, has proven to work extremely well in the cancer setting (some details are here). A massive contribution of the CNS is widely thought has been thought to be the “proctive case management”, and not only is this is sound clinical sense but could in the long run save the NHS millions, averting emergency hospital admissions which have been pre-empted. The case for proactive case management has also been established in other neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis. CNS have been described well for the community, but also have a rôle to play in hospitals. Indeed, continuity of care between the community and hospital will be vital, not least because people living with dementia can find unfamiliar people and physical environments extremely distressing. Warrington has seen the introduction of designs which put people living with dementia at ease and the valuing of specialist trained staff. The service provision there is a beacon of success, and shows what can be done if the NHS has a vision and motivation to succeed in this.

CNS could have been a pivotal component of the answer given to Lorely Burt, Liberal Democrat MP for Solihull, this week to the Prime Minister in the weekly PMQs. But it sadly was not.

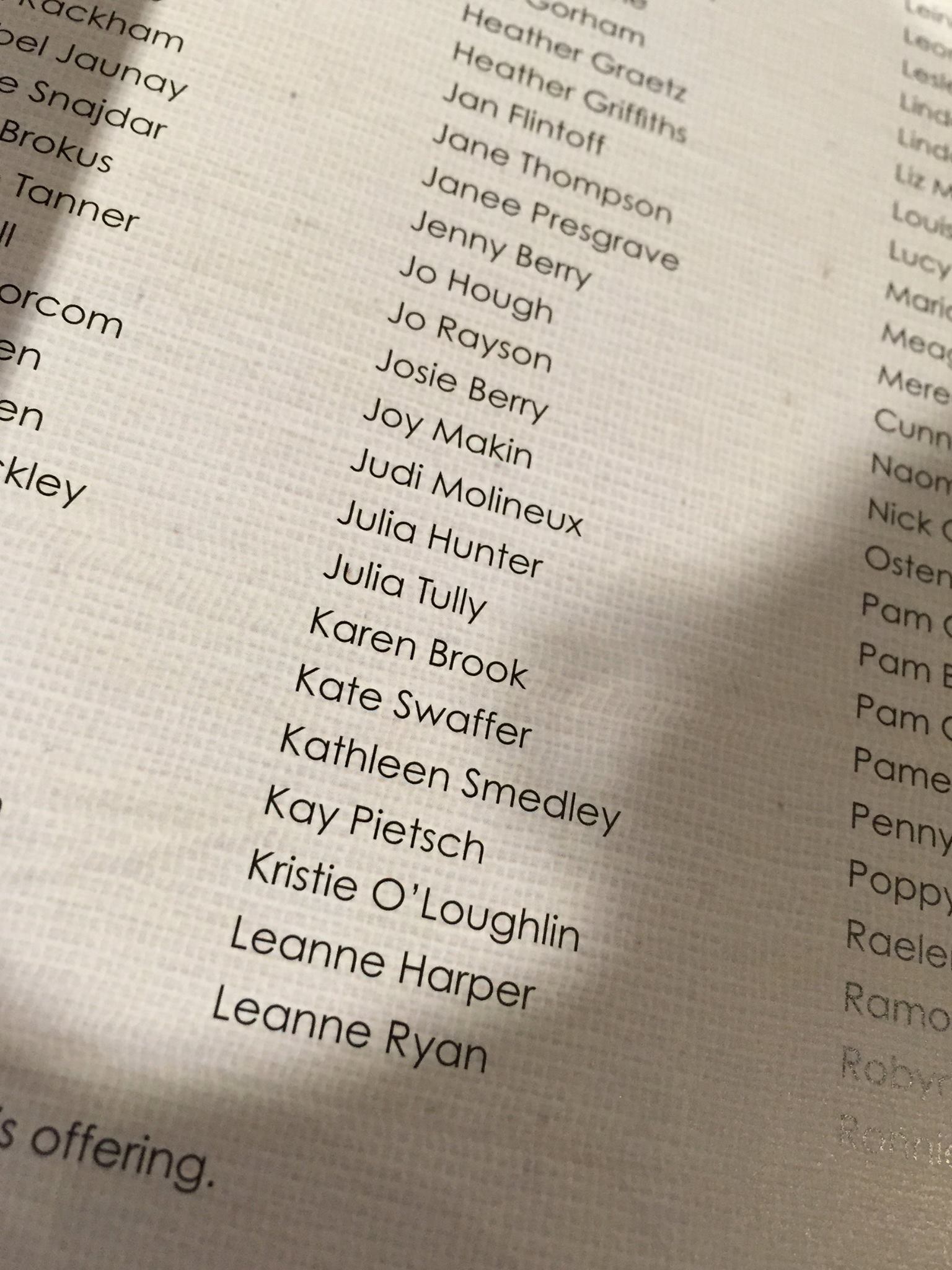

Clinical nursing specialists, including the well respected “Admiral nurses” from the ‘Dementia UK’ charity, have been recognised as being crucial to developing world class care in dementia too here from our own English nursing strategy. Over 4o00 have signed a petition for more Admiral nurses on the internet. A much under-reported item of research from the Centre for Innovation and Leadership in the Health Sciences at the University of Southampton, established improved clinical outcomes and significant return on investment from CNS in dementia. Again, work in progress suggests that the proactive case management approach has a lot to offer here. A paper from Prof Steve Iliffe and Prof Jill Manthorpe and colleagues is particularly noteworthy here. The beneficial impact of CNS in averting emergency admissions is being well described for cancer by Prof Alison Leary, Chair of Healthcare and Workforce Modelling, and colleagues (see, for example, here). If in the next five-year English dementia strategy there is a strong commitment to flagship clinical integrated services with well established and respected clinical nursing specialist models implemented, this could really revolutionise dementia service provision. And it’s now becoming increasingly that commonalities in what works well, especially in relation to involving caregivers, is working across a number of LTCs. This is a golden opportunity for senior policy specialists in dementia to put the emphasis on sustainable models of care rather than shiny box gimmicks, and to design a system which will be of real benefit to patients with dementia and their closest ones.