A ‘Big Mango’ has just gone missing, but will people notice if Big Data suddenly goes missing for the purposes of research into dementia?

A large ceramic mango is of course tangible property, whereas the information itself of ‘Big Data’ isn’t. But the recent furore over ‘caredata’ has illustrated how meticulously careful if you have to be about consent.

Twitter is amazing.

During infectious disease outbreaks, data collected through health institutions and official reporting structures may not be available for weeks, hindering early epidemiologic assessment.

In contrast, data from informal media are typically available in near real-time and could provide earlier estimates of epidemic dynamics. Many people for ‘breaking news’ nowadays prefer to do a Twitter search than wait for a news bulletin.

Rumi Chanara and colleagues (Chanara et al., 2012) assessed correlation of volume of cholera-related HealthMap news media reports, Twitter postings, and government cholera cases reported in the first 100 days of the 2010 Haitian cholera outbreak.

Trends in volume of informal sources significantly correlated in time with official case data and was available up to 2 weeks earlier. They found that informal data can be used complementarily with official data in an outbreak setting to get timely estimates of disease dynamics.

The English law does pride itself, however, on some sort of law on the protection of information (hence the enactment of the Data Protection Act 1998).

Long before that, Oxford v Moss (1979) 68 Cr App Rep 183 was an English criminal law case, dealing with theft, intangible property and information. The court ruled that information could not be deemed to be intangible property and therefore was incapable of being stolen within the Theft Act 1968.

The defendant, Moss, was a University student and managed to obtain a proof copy of his forthcoming exam paper. It was accepted that he always intended to return the proof itself, and therefore could not be convicted of theft of the proof itself, however he was charged with stealing information belonging to the Senate of the University.

How confidential medical data are dealt with has been cause for a broohaha recently.

Informed consent is an ‘opt-in‘ model:people have to sign up to donate organs. In this model, donors must also be made aware of what they are signing up for and have the option of withdrawing their consent at any point.

Informed consent contrasts with presumed consent (used in association with organ donation, the assumption that an individual is happy to donate organs after death unless he or she has explicitly said that they do not wish to).

At the beginning of February 2014, it was reported that the Information Commissioner’s Office had been concerned that the information provided to patients on care.data is not clear enough about how to opt out of the programme.

According to Prof Brian Jarman, an expert statistician whose interests data and public health, the arrangements concerning ‘caredata’ do not sound like informed consent.

“The Data Protection Act (DPA) usually requires organisations by default to offer opt-in. Yet for the confidential care.data opt-out is the only option. This suggests a lack of informed consent. The leaflet sent to people in their junk mail gives little information about the drawbacks. To have informed consent patients need to be told of the risks as well as the benefits.”

This was a bit of a public grab, but possibly competing in publicity with the latest finding that thieves have just made off with a 10 metre high, 10 tonne mango replica from a town in northern Queensland, Australia.

A crane was used to rip the three-storey giant fruit from the concrete platform on which it had stood since 2002.

Just as people are now vigilant about the theft of giant mangos, the theft of Big Data has come under justifiable scrutiny.

Already there has been the massive plastic card data theft in South Korea, affecting about 60 million cards; the Target Corp. credit card disaster involving up to 40 million customers; the hacking of 16 million German e-mail accounts; data securitybreaches at Nieman Marcus Inc. and Easton-Bell Sports Inc.; and a group of Russian hackers who compromised the computer systems of Western energy and defense companies, governments, and academic institutions.

Cybercriminals, of course, abuse less obvious vulnerabilities, such as those in site-building software. In these cases, they often buy malware rather than develop it themselves.A specialised field, the grab of Big Data has particular relevance to people worried about hackers of a giant database of NHS clinical data.

So are Big Data important? An article in Wired Magazine “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete ” cited provocatively that, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

So proclaimed statistician George Box 30 years ag.

In this article, it was stated that the scientific method is built around testable hypotheses but some of the models have not actually been that good, in comparison with real data.

Mendel and Newton are cited.

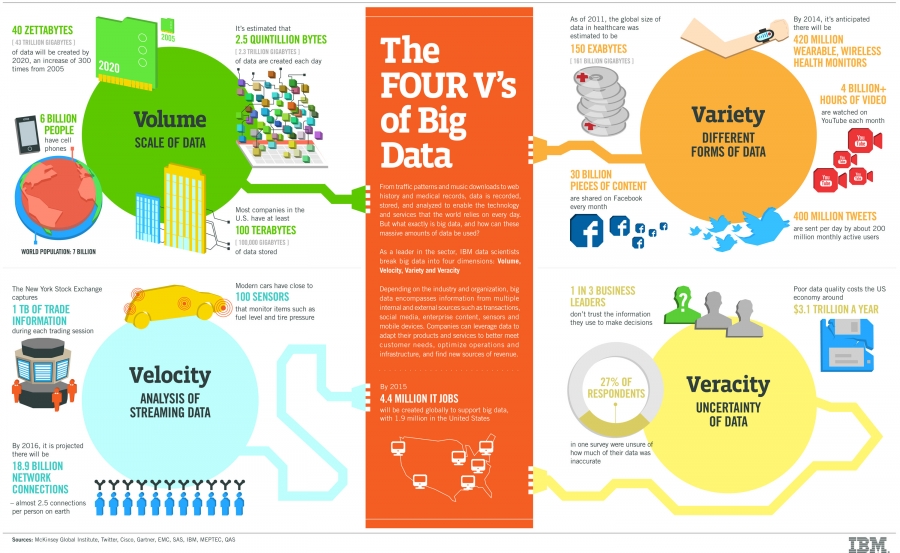

According to McKinseys, the amount of data in our world has been exploding, and analyzing large data sets—so-called big data—”will become a key basis of competition, underpinning new waves of productivity growth, innovation, and consumer surplus”.

In October 2012, it was reported that Massachusetts General Hospital would receive $5.4 million from the nonprofit Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, in what the fund said was the largest single private scientific grant ever invested in Alzheimer’s whole-genome sequencing.

The Alzheimer’s Genome Project would obtain complete genomic sequences of more than 1,500 patients in families that have Alzheimer’s, and will include over 100 brain samples. The genomes of family members with Alzheimer’s will be compared to those members who have been spared the disease to identify sites in the genome that influence risk for Alzheimer’s.

And it does seem as if people are generally moving with the times,.

In January 2014, for the “Nuffield Council on Bioethics: The linking and use of biological and health data” a response by the Wellcome Trust from January 2014 provided a number of interesting points.

“The linking and use of biological and health data is central to a wide range of biomedical research. There is a strong need to ensure a legal and regulatory environment in which these data can be used and linked for the purposes of research that aims towards improving health.”

However, the following was also noted.

“There are legitimate ethical concerns about the privacy implications of the use and linking of such data and future developments in using these data cannot necessarily be anticipated. Participants’ wishes are paramount, and there is a need for strong governance mechanisms for the use of participant data in research that can appropriately protect participant confidentiality.”

Google Health had to give up, however, with their initiative:

“Now, with a few years of experience, we’ve observed that Google Health is not having the broad impact that we hoped it would. There has been adoption among certain groups of users like tech-savvy patients and their caregivers, and more recently fitness and wellness enthusiasts. But we haven’t found a way to translate that limited usage into widespread adoption in the daily health routines of millions of people.”

Of course the grab of a giant mango can only put down to a publicity stunt; sharing of data for the public good in no way constitutes theft if done with the informed consent of people involved, although regulators have ingenious ways of making certain things permissible as they wish.

Stealing a giant mango is hardly likely to be legislated for in the near future, however.