To be clear, I think the work of the Alzheimer’s Society is fantastic.

Since their restructuring, with the support of the Department of Health, they have done really important work in activities to do with dementia, not just Alzheimer’s disease.

Goliath (Hebrew: גָּלְיָת,) is a a giant Philistine warrior defeated by the young David, the future king of Israel, in the Bible’s Books of Samuel (1 Samuel 17).

Britain’s energy market is said to be dominated by the Big Six gas and electricity suppliers. All markets need competition to function effectively, with genuine choice for consumers.

Mentions of the Alzheimer’s Society are extensive.

This is for example Hazel Blears on 16 December 2013:

And here is the recruitment drive of Jeremy Hunt, four minutes in into his speech at the G8 Summit in December 2013:

It really has become a gigantuan operation for smaller charities to compete also in the social media:

Last week, it was announced that staff at Marks & Spencer, Argos, Homebase, Lloyds Bank and Lloyds Pharmacy will attend special sessions to help them understand the needs of customers with dementia and support them better.

The Alzheimer’s Society makes clear that the drive towards ‘Dementia Friends’ forms part of the six-month progress report on the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia.

And it has been a success we can all be proud of. Norman McNamara is also soldiering on with his “Dementia Friendly” Torbay initiatives.

As a result of commitments from various businesses regarding “Dementia Friends”, over 190,000 staff will become Dementia Friends – 60,000 from M&S, 70,000 from Lloyds Pharmacy, 50,000 from the Home Retail Group, which owns Argos and Homebase, and 11,500 from Lloyds Bank.

And yet ‘dementia friendship’ is a global initiative.

Supportive communities are well known in Japan. For example, Fureai kippu (in Japanese ふれあい切符 :Caring Relationship Tickets) is a Japanese currency created in 1995 by the Sawayaka Welfare Foundation so that people could earn credits helping seniors in their community.

An initiative from another charity, the Joseph Rowntreee Foundation, “York Dementia Without Walls” project looked into what’s needed to make York a good place to live for people with dementia and their carers.

They found that dementia-friendly communities can better support people in the early stages of their illness, maintaining confidence and boosting their ability to manage everyday life.

There are various reasons why it is so easy for the Alzheimer’s Society to ‘clean up’ in the dementia charity market in England.

These are helpfully summarised in this summary slide, derived from the work of Michael Porter, Bishop William Lawrence University Professor of Business Management at the Harvard Business School, USA.

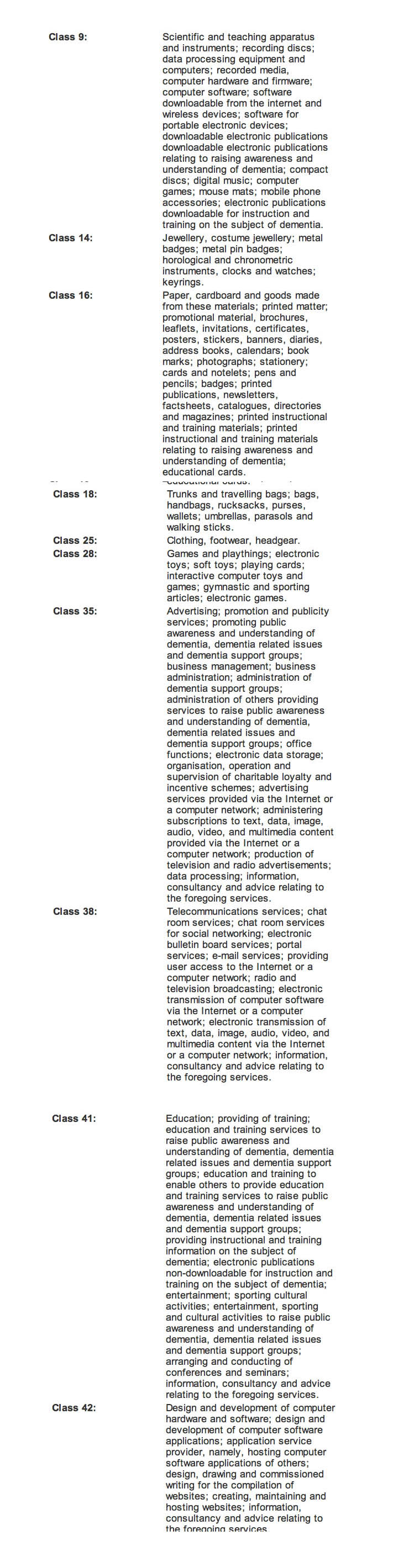

The Alzheimer’s Society have protected their visual mark for “Dementia Friends” on the trademark register for the IPO, as trademark UK00002640312. It is protected under various categories. This is across various classes, including ‘gymnastic and sporting articles’.

It would have cost a lot for the Alzheimer’s Society plus the cost of instructing their lawyers, which are cited here as the big commercial/corporate law firm DLA Piper in Leeds. It’s simply impossible for smaller charities to compete resource-wise over this arm of intellectual property.

Currently, according to the UK trademark office, it costs £170 to apply to register a UK trade Mark if you apply on-line (£30 discount applies for on-line filings). This includes one class of goods or services. It is a further £50 for every other class you apply for.

And the pattern of news stories about dementia has now reached a consistent homogeneous pattern. For example, this story about Prunella Scales being diagnosed with dementia has a standard line with the word ‘suffering’ (“Fawlty Towers star Prunella Scales is suffering from dementia – but is determined not to let it stop her performing, her actor husband Timothy West has revealed.”)

But the language is not one of ‘living well with dementia’, consistent with other metaphors such as ‘timebomb’, ‘explosion’, ‘flood’ and ‘tide’.

And crucially it is very rare to have any other dementia charity named apart from the Alzheimer’s Society because of their strong brand presence inter alia.

There are other dementia charities in England, however.

BRACE is a registered charity that funds research into Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Their role is to help medical science understand the causes of dementia, find ways of diagnosing it earlier and more accurately, and develop more effective treatments.

Dementia UK is a national charity, committed to improving quality of life for all people affected by dementia. They provide mental health nurses specialising in dementia care, called Admiral Nurses. And yet there have been cuts to the Admiral Nurses service.

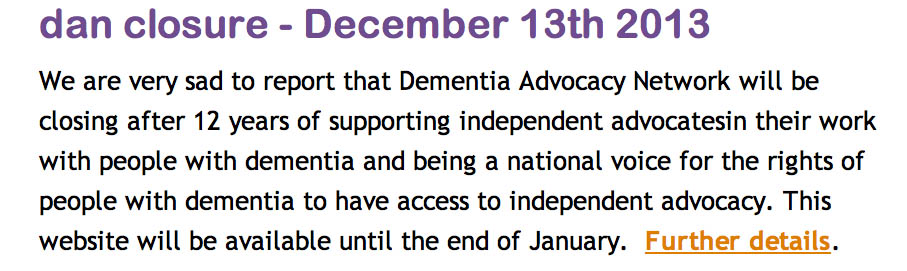

On December 13th 2013, the Dementia Advocacy Network reported that they would be closing after 12 years of supporting independent advocates (this is the current link to their website.)

An article in the European Journal of Marketing (Vol. 29 No. 10, 1995, pp. 6-26), entitled “The market positioning of British medical charities” by Sally Ann Hibbert from Department of Marketing, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland, does throw some light on this issue.

Hibbert notes that clusters of people who donate to charities exist overall.

“Following on, the next highest scores are revealed for cancer and deaf charities, the former investing notably in education and research for cures, the latter focusing largely on treating the effects of deafness to improve the quality of life for people affected. This trend from preventive approaches to care services can be traced down through the charities on the vertical dimension to hospices, which are primarily carers.”

In the absence of a reliable marker through scans or psychology before symptoms, and in the absence of good treatments of dementia which stop the condition “in its tracks“, it was hard to make the pitch for molecular biology research and treatments. The industry was described as “ailing“.

That’s why it was so crucial to compare dementia to AIDS (see video above).

There is a legitimate concern that driving policy towards limited angles in this way could obscure the need for funding a grossly under-resourced community care services for dementia.

And living well with dementia is an appropriate policy plan for persons currently with dementia and their caregivers.

But specialist groups of people with dementia are beginning to emerge. For example, the “Dementia Action Alliance” is a non-profit dedicated to improving the quality of life for people living with the effects of dementia.

The DAA Carers Action (@DAACarers) also do incredible work .

Like the Government has been to provide an “equal playing field” for any qualified provider of NHS services, it is impossible to think that the playing field for raising money for dementia through charities and people such as the Purple Angels is anything like an “equal playing field”.

This is a major flaw in current policy, and could mean that there are some losers and some winners. This ‘zero sum gain’, simply, is not on I feel.

It is deeply concerning that “might is right”. We should try to work together.