There’s been a persistent concern amongst many academics and amongst many persons with dementia themselves that persons with dementia are not at the heart of decision-making in dementia-friendly communities.

The notion of ‘no dementia about me without me’ has not been rigorously applied to dementia-friendly communities, with directors of strategy in corporates seeking to consider how to make their organisations dementia-friendly as part of a corporate social responsibility or marketing strategy.

Such directors are obviously fluent in how to present such a strategy as elegant marketing, to secure competitive advantage, to make money, so it makes absolute sense for them.

It also makes sense for the Department of Health and the Alzheimer’s Society, who are seeing through the policy of ‘Dementia Friends’ through a sustainable financial arrangement, to see this policy plank politically flourish. With every single newspaper article on dementia now mentioning ‘Dementia Friends’, it is hard to see how this campaign cannot succeed.

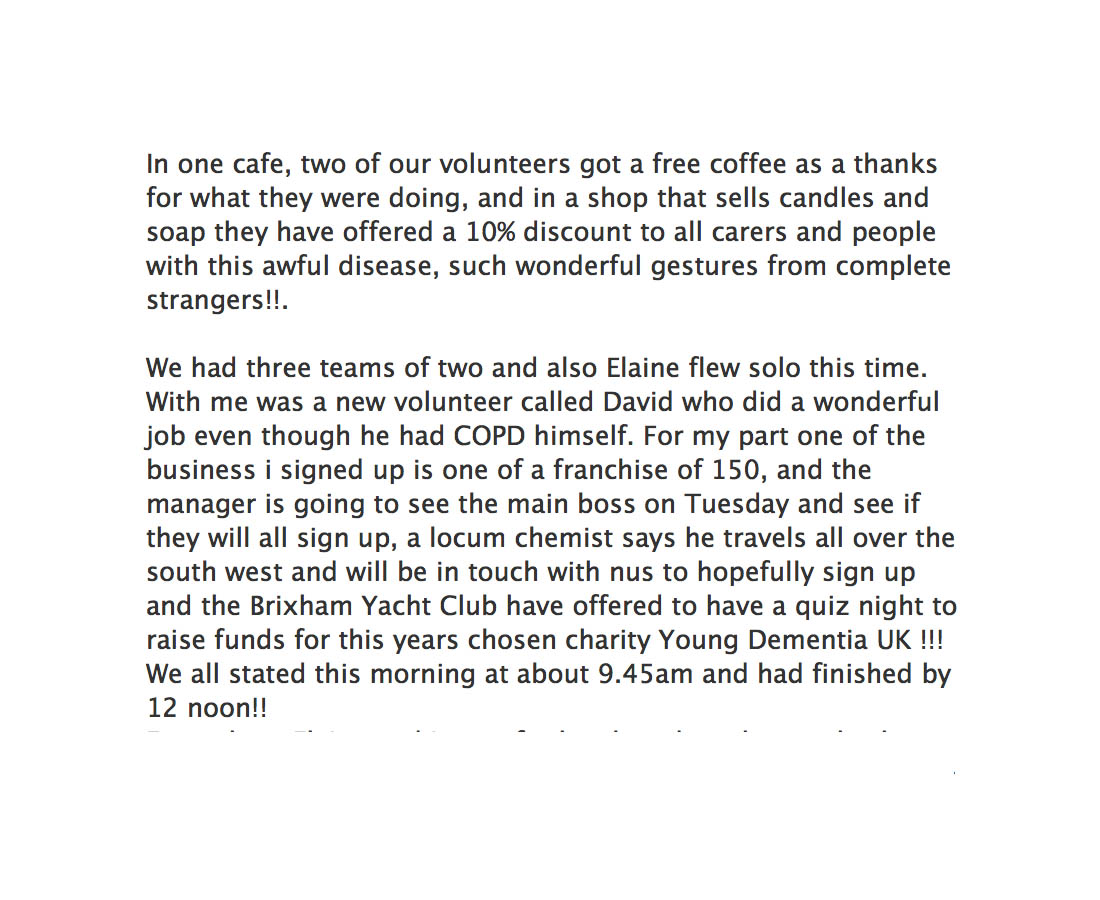

Norman McNamara, an individual campaigning successfully and living with dementia of Lewy Body type, reported yesterday on Facebook local success around the Brixham community area.

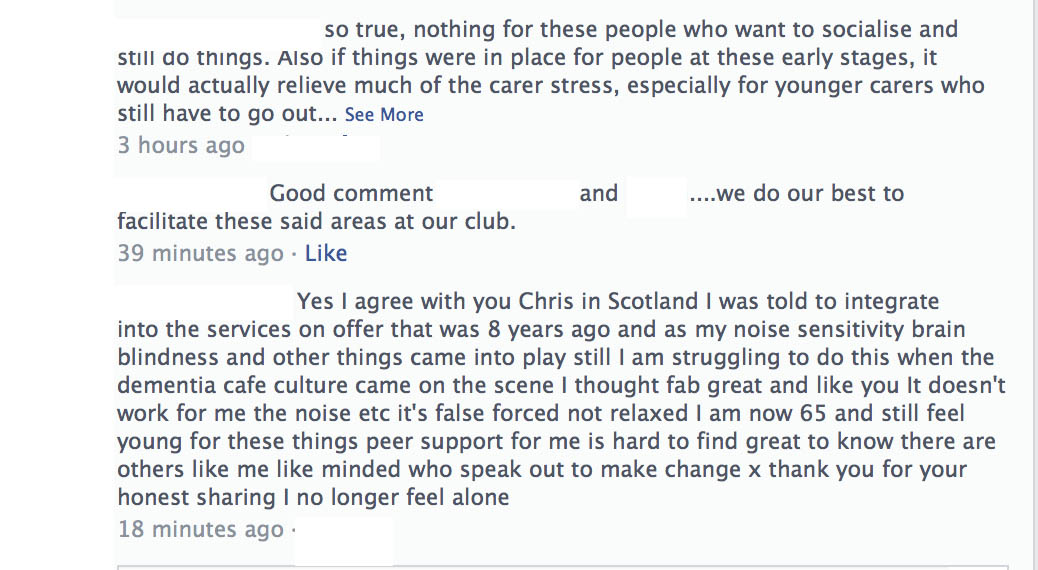

Chris Roberts, another person in his 50s living with a dementia, also mooted the idea of setting up cafés himself.

“Since being diagnosed, i’ve noticed that there isn’t a lot for people in the mild to moderate stage. There are dementia cafes of course, but these seem to suit carers more than the people with dementia, we just sit there smiling when looked at while our carers and spouses chat away to each other, sharing there experiences and so on.”

“There are 100s of thousands of us in the same positition with nowhere to go or nowhere to be left! We could popin for an hour or for the day. We could practically run the place our selves, some where we could chat and share, watch tv, play cards, draw , we would arrange our own activities not led by someone who thinks they know what we want!”

“Yes we can live with dementia, yes we could even live well ! Yes we could live even better !”

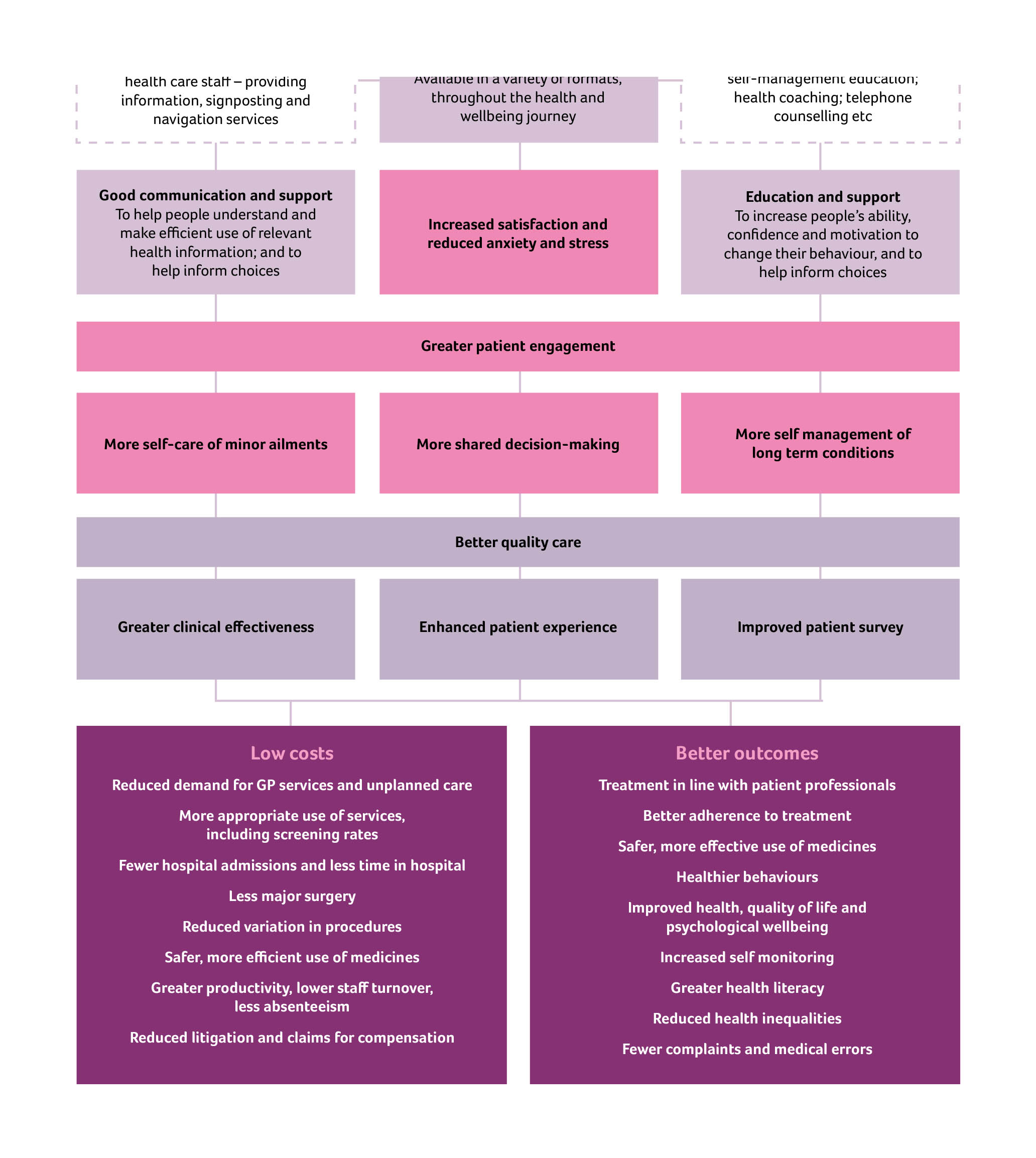

The “living well with dementia” philosophy is all about enabling people to pursue what they can do rather what they cannot do. There’s a chapter on activities in my thesis on living well with dementia, reflecting the fact that activities are not only promoted in the current National Dementia Strategy but also in NICE Quality Standard 30 ‘Supporting people living with dementia’.

The National Dementia Strategy makes reference to such activities being ‘purposeful‘:

And this gets away from the concept of persons with dementia sitting around calmly doing knitting when they might have been, for example, proficient motorcycle bikers:

When one criticises that persons with dementia are often not at the heart of decision-making, these days I get a standard reply saying, ‘we always take serious note of the opinions of people with dementia; in fact there are two representatives on our board.’

Yet personal feedback which I receive is that persons with dementia resent this “tokenism”.

Having persons with dementia at the heart of decision-making I feel is important in the campaign to overcome stigma and discrimination against persons living with dementia. Persons with dementia running businesses of their own dispels the notion that persons with dementia are incapable of doing anything at all.

As a Fellow of the RSA, I intend to apply for a RSA Catalyst grant, as well as to the Wellcome Trust (who funded my own Ph.D. in decision-making in dementia fewer than 15 years ago now), to investigate collective decision by people in earlier stages of living with dementia to see how they in fact shape their community.

I am hoping that this will be in the context of their ongoing research work with the RSA Social Brain project, and I am hoping to hear from other Fellows about their work there, shortly. I will be putting my grant in with various people who are genuinely interested in this project.