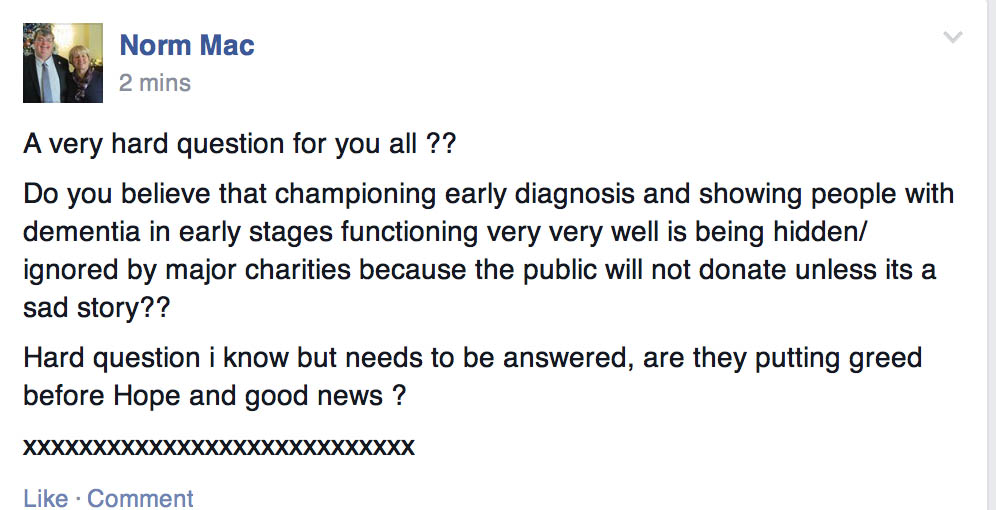

I am about to present to you a proposal for a change in behaviour from ‘dementia friendly communities’ to putting the boot on the other foot, persons with early dementia leading communities with their beliefs, concerns and expectations. I would be enormously grateful for any feedback on my ideas, which I’m deadly serious about it.

For example:

Many thanks already for these other kind remarks on Twitter:

Anyway here it is.

Introduction

It’s virtually impossible for anyone to lead on “dementia friendly communities” in a charismatic way because of the lack of clear vision so far in what a dementia friendly community is. And yet there are clearly structural fault lines in which this debate has been approached by a number of influential parties. At worst, the policy has been engulfed by commercial considerations of people seeking to make an ‘economic case’, finding clear routes by which becoming ‘dementia friendly’ can generate business or profit. The policy fundamentally has huge flaw in it currently. It treats people living with dementia as one big mass of people, with no consideration of the hundred or so different types of dementia.

Consequently, absolutely no effort is made as to considering what people with dementia can do, rather than what they can’t do. For the purposes of my leaflet, I propose further work using the foundations laid by the RSA’s “Social Brain” project in light of the #powertocreate initiatives at the heart of the RSA’s philosophy. I feel that a powerful breakthrough will be made if we can try to extend the woefully small body of work on self-s of thinking and Self in the neuroscientific literature. The current constructs of ‘dementia friendly communities’ are so bland that they might work equally well for ‘cancer friendly communities’. I also feel that if we try to allow people with early dementia a chance to harness abilities rather than disabilities, this might produce a useful entry route for collective decision making by people with early dementia.

A problem with disengagement

Ambitious, but quite pragmatic about this promise, the RSA is an organisation recently committed to the pursuit of what it called a “21st century enlightenment”. Founded in 1754 during the actual historical Enlightenment, its purpose – realised through its projects, public lectures and Fellowship activity – is to identify and release untapped human potential “for the common good” and in so doing foster a society in which citizens are more capable of acting confidently, altruistically and collaboratively.

The ultimate question for the RSA’s “Social Brain project” is whether a change in how we think of ourselves can lead to a change in our culture overall, which in turn can lead to effective responses to our shared problems. I am going to take one ‘problem’ how we encourage a sense of community in persons living well with early dementia. In the original ‘Enlightenment’, knowledge about how the world functions led to changes in the way human beings conceived of themselves. Most notably, the success of scientific knowledge led to people beginning to view themselves as not governed by divine powers, but as capable of shaping their own destinies through the power of reason. There has been a massive explosion in our understanding of the brain, and indeed the dementias. The Social Brain project is interested in how new knowledge about brains and behaviour might lead to a similarly powerful invigoration of people’s ability to shape their own destinies.

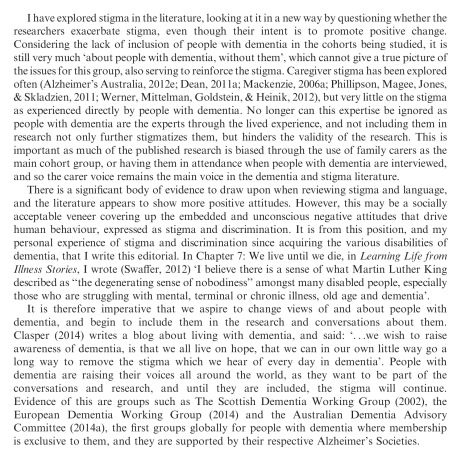

Take, for example, the life and work of Kate Swaffer regarding dementia.

Kate has clearly taken it in her own hands to shape her own destiny, campaigning on dementia. She lives with a dementia in Australia herself, and refuses to be ‘talked at’ or ‘talked about’. Her blog produces insights into living with dementia which should be compulsory reading for medical professionals who have little experience in personhood.

This is an extract from Kate’s blog.

Following a diagnosis of dementia, most people are told to go home, give up work, in my case, give up study, and put all the planning in place for their demise such as their wills.

Their families and partners are also told they will have to give up work soon to become full time ’carers’. Considering residential care facilities is also suggested.

All of this advice is well-meaning, but based on a lack of education, and myths about how people can live with dementia. This sets us all up to live a life without hope or any sense of a future, and destroys our sense of future well being; it can mean even the person with dementia behaves like a victim, and many times their care partner as a martyr.

Many of you know I have labelled this “Prescribed Disengagement”, and it is clear from the numbers of people with dementia who are standing up and speaking out as advocates that there is still a good life to live even after a diagnosis of dementia.

My suggestion to everyone who has been diagnosed with dementia and who has done what the doctors have prescribed, is to ignore their advice, and re-invest in life.

This ‘prescribed disengagement’ can be further exacerbated by any ‘dementia friendly communities’ where the key outcome is a badge or a sticker in the window, rather than ascertaining the beliefs, concerns or expectations of persons living with one of the dementias.

A growing democratic deficit with persons with early dementia?

Dementia describes different brain conditions that trigger a loss of brain function. These are all usually progressive and eventually severe. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, affecting 62 percent of those diagnosed. Other types of dementia include; vascular dementia affecting 17 percent of those diagnosed, mixed dementia affecting 10 percent of those diagnosed. Symptoms of dementia include memory loss, confusion and problems with speech and understanding.

What goes wrong in thinking, and the underlying problems in the brain, is now reasonably well established for the commonest form of dementia at least.

A good review is provided by Peña-Casanova and colleagues from 2012. The progression of brain pathology determines the cognitive expression of the disease. Thus, in accordance with the initial involvement of a part of the brain close to the ear medial temporal lobe, thinking changes in Alzheimer’s Disease typically start with specific difficulties in encoding and storage of new information. There is therefore quite a lot which persons with Alzheimer’s Disease can do, not of course meaning to dismiss in any way such problems with new information. A similar argument can be made for other types of dementia such as posterior cortical atrophy or progressive primary aphasia.

That persons currently living with an early dementia are not supposed to be the prime recipients of the mass of news stories about dementia is witnessed in the use of the words ‘timebomb’, ‘flood’ or ‘tide’ by influential politicians. A democratic deficit (or democracy deficit) occurs when ostensibly democratic organisations or institutions (particularly governments) fall short of fulfilling the principles of democracy in their practices or operation where representative and linked parliamentary integrity becomes widely discussed. It’s said that the phrase democratic deficit is cited as first being used by the Young European Federalists in their Manifesto in 1977, which was drafted by Richard Corbett. The phrase was also used by influential thinker Prof. David Marquand in 1979, referring to the then European Economic Community, the forerunner of the European Union.

As Dr. Jonathan Rowson puts it at the beginning of his report with Iain McGilchrist “Divided brain, divided world”, we are fundamentally social by nature:

“The notion that we are rational individuals who respond to information by making decisions consciously, consistently and independently is, at best, a very partial account of who we are. A wide body of scientific knowledge is now telling us what many have long intuitively sensed – humans are a fundamentally social species, formed through and for social interaction, and most of our behaviour is habitual.”

There’s little doubt over the broad definition of a “dementia-friendly community” as one in which people with dementia are empowered to have high aspirations and feel confident, knowing they can contribute and participate in activities that are meaningful to them. However, there is little attempt to demarcate the limits of that community, possibly unnecessary when you consider that multinational corporations are capable of using the term globally?

A lack of a wish to put people with early dementia in the driving seat in dementia friendly communities is indeed maintained by persistent references by think tanks to dementia as a “disease”, whereas policy has been firmly been moving towards considering people as individuals.

The aspiration that one might shape communities around the needs and aspirations of people living with dementia “alongside the views of their carers” tends to assume somewhat that persons with dementia and carers will have similar views and attitudes. Each community will have its own diverse populations and focus must include understanding demographic variation, the needs of people with dementia from seldom heard communities, and the impact of the geography, e.g. rural versus urban locations.

A lot of media attention has latterly gone into the notion of respectful and responsive businesses and services. An aspiration to promote awareness of dementia in all shops, businesses and services so all staff demonstrate understanding and know how to recognise symptoms is fine, provided that such ‘badges of honour’ are not consigned to leaflets which people make available passively.

If one is not careful, this policy can see an insidious strand of ‘Nudge’ invoking a nasty whiff of corporate bias in influencing consumer behaviour. For example, a member of public might start making shopping choices according to those people who haven’t accorded themselves the label of being ‘dementia friendly’. Such arrival of consumer choices by elimination is known as ‘elimination by aspects’, a highly influential theory of economist Anne Tversky whose work contributed to the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002. Such an approach reinforces power to a top down Élite, and not putting persons with dementia at the heart of communities.

Dementia friendly communities cannot simply be about ‘Nudge’

There are some nudges that appear to actively engage individuals. For example, where choices are contextualised as public commitments, changes in behaviour tend to be more pronounced. This looks like active engagement whereby a person thinks for herself in order to change her own behaviour. But this change in behaviour is actually driven by various emotions that are triggered in the automatic system; emotional responses such as wanting to maintain one’s reputation, avoiding the shame of not sticking to one’s commitment, and wanting to appear consistent (for one’s behaviour to align with what one has said). Reputation has previously been identified by Professor Michael Porter at Harvard as a key factor through which corporates wish to prove their citizenship in ‘corporate social responsibility’.

However, it is commonly argued that “the Nudge approach” can only work on very simple behaviours: ones where the automatic system can be guided without any input from the controlled system. Very few behaviours are indeed simple enough to be influenced in this manner.

Libertarians, such as New York University Professor Mario Rizzo and California State University Northridge Professor Glen Whitman, have publicly expressed heir political reservations as concerns about nudges being “vulnerable” to becoming tools that support new, straightforwardly paternalist policies. They specifically warn that ‘nudge projects’ could grow expansively, absorb public resources, and primarily further the ends that choice architects (notably, government bureaucrats) deem valuable. At worst, this is what has happened with the mass roll-out of the corporate involvement of dementia friendly communities.

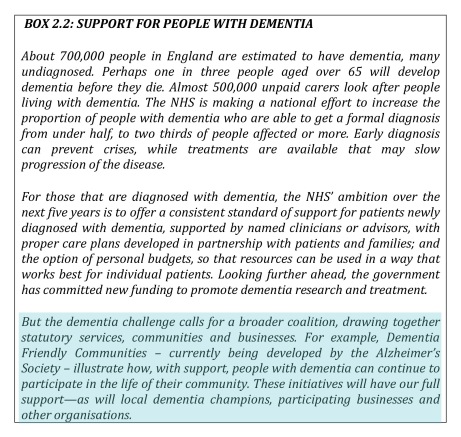

A desire by persons with early dementia to be engaged in dementia friendly communities

Norman McNamara, living with a type of dementia known as diffuse Lewy body disease, has campaigned tirelessly in raising awareness of dementia, and this work does not merit any criticism at all. I know several people who’ve drawn enormous benefit from the fact that shops are showing the ‘Purple Angel’ sign in their shop window, offering genuine reassurance. But a problem is a lack of interest by some funding bodies and politicians in giving persons with early dementia up to date information about the neuroscience and research in dementia, and encouraging feedback on such information. Involving people with early dementia is not as impressive as persons with dementia making decisions to fulfil their own plans with appropriate support. Take for example Chris Roberts’ desire to set up a café.

“There are 100s of thousands of us in the same positition with nowhere to go or nowhere to be left! We could popin for an hour or for the day. We could practically run the place our selves, some where we could chat and share, watch tv, play cards, draw, we would arrange our own activities not led by someone who thinks they know what we want!

no one leaves till they are collected, could it be so easy, there are 1000′s of empty buildings in every major city in the uk .”

When I spoke to Chris over the phone over this, Chris reported to me that it’ll always be the case that some persons with dementia do not wish to become particularly involved in the democratic process. This of course is not particularly surprising, given that it is estimated that up to a million people will not bother voting in the UK general election to be held on May 7th 2015. Significantly, Chris is less keen himself personally to be a recipient of funding or grants, as he appreciates that involving a financial backer could immediately make him accountable to another party, diverting energy from the real purpose of this project – as community action.

Real engagement is nonetheless possible. Marian and Shaun Naidoo have been commissioned by the combined commissioning group to undertake “Connected Compassionate Communities” in Birmingham and Solihull. The overarching aim of this action research project is to improve the lives of frail older people and the people who care for them.

In the preliminary stages of this project, feedback from all stakeholders who have an interest in improving a care pathway for dementia. Marian and Shaun concluded the following:

“there is no doubt that many people have a positive experience of diagnosis and do live well with dementia. Conversations with people within this process identify concerns with regard to lack of awareness and knowledge at every stage of the pathway. This was perceived across all sectors. Many people experienced delays in diagnosis, lack of connected support and stigma. The scope for developing better services through trust and greater engagement remains.”

Asking the right questions – how much do we really know about ‘self awareness’ in persons with early dementia?

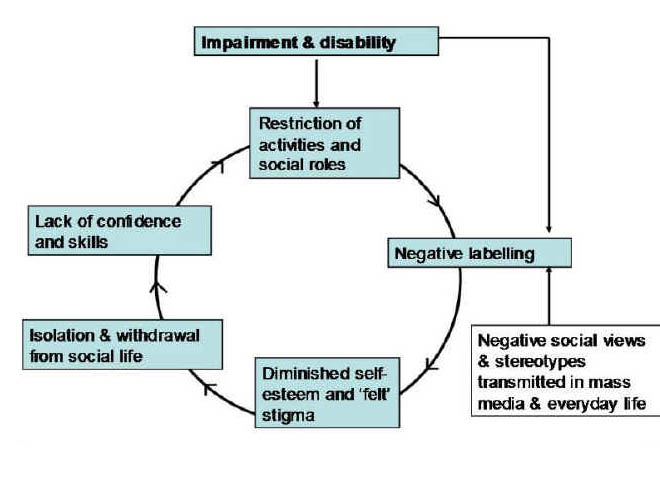

According to Ballenger (2006), a major problem lies in the very character of biomedicine, in its inability to deal adequately with uncertainty. The efforts of the medical professions have been hampered through a range of different perspectives on the nature of dementia as a ‘disease process’, the lack of an effective treatment for symptoms or preventing further progress of the disease, and the ambiguous consequences of receiving a diagnosis as far as support from the medics are concerned. Social stigma further complicates this struggle, as individuals diagnosed with dementia can often find themselves disempowered, disassociated, and excluded from social networks.

Nonetheless, despite the tremendous loss of identity that occurs over the course of a dementing illness, it is also established that a sense of Self can survive, as demonstrated by the uniqueness of each person living with a dementia (Dworkin, 1986).

In a study of individuals diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer’s disease, the common failure to recognise the individual’s continuing awareness of Self was found to lead to low expectations for therapeutic intervention, to interactions that are limited to the task at hand (such as activities of daily living). This cumulatively led to less than optimal experiences for a given level of dementia.

Clare (2003) has identified a range of responses to changes in memory function, from ‘‘self maintaining,’’ in which these persons work to maintain existing identities, to ‘‘self-adjusting,’’ in which individuals develop a new sense of self by incorporating changes into their new identity. Saunders (1998) found that “dementia patients still perform a great deal of identity construction and maintenance (p. 85).” According to Saunders, these accounts demonstrate a fluctuation in self-perception by individuals with dementia as they cope with the memory changes they experience. But clearly one should never try to inflict information about dementia to persons with dementia, if there is any risk that this might cause distress or offends autonomy in persons living with early dementia. But then it becomes a ‘catch 22’ – you need to raise awareness due to the stigma to do with dementia, but the stigma or genuine fear causes persons with dementia and caregivers wishing to engage with the science of the condition even remotely.

In this regard, Portacolone and colleagues in the journal “Aging and Mental Health” in an article entitled “Time to reinvent the science of dementia: the need for care and social integration” provide extremely useful insights.

“To rethink its basic orientation, the recent biomedical trend in dementia needs to mature out of its stage of confidence. Ballenger suggested a more self-reflective and explicitly ambivalent biomedicine – an ‘aging’ biomedicine willing to open to other fields and disciplines concerned with dementia. Along those lines, other speakers suggested we rethink the biomedical paradigm of healing and replace it with a holistic paradigm of care, empathy, as well as cultural and social integration. This reframing can be facilitated through a dialogue between biomedicine and bioethics, public health, social sciences, and the medical humanities, as illustrated by the richness and depth of the discussions generated at the workshop. To assist this reframing, we begin with a reflection on the main elements of the struggle that is compelling biomedicine to rethink its original orientation: the unsettled definition of dementia comes first, followed by the ambiguous benefits of the diagnosis, the ethical conflicts on consent and clinical trials, and finally the need to give more attention to the perspective of the person with dementia. The conclusion discusses the opportunities of a new holistic paradigm founded by a dialogue between biomedicine and public health, social sciences, medical humanities, and bioethics.”

And it could be we’re all looking at different parts of ‘dementia friendly communities’ from different viewpoints.

In the story of “The Elephant in the Dark”, the medieval Farsi-speaking poet Rumi masterfully portrayed the limitations places on beliefs by noisy sensory perception (Tourage, 2007). Late one evening, an Indian circus arrived at a village. The more curious villagers sneaked into the elephant’s stable. In absolute darkness, they made observations by touching the elephant’s body When they returned to their families, their accounts, constrained by their limited sensory experiences, gave widely divergent images of the elephant.

Rumi concluded that “light” —an external source of objective reference—is necessary for formation of reliable beliefs about the external world. Without objective reference, beliefs will be purely subjective. It is an impossible task, I feel, to look at ‘dementia friendly communities’ for persons living with an early dementia, with putting the views of those people at the heart of the decision-making process.

Public engagement with persons with dementia does not necessarily need to involve the traditional media, but it probably helps!

We currently live in a time when the scientific establishment, the government andfunding bodies, are voicing concern about the relationship between science and the public. The call is for improvements in this.

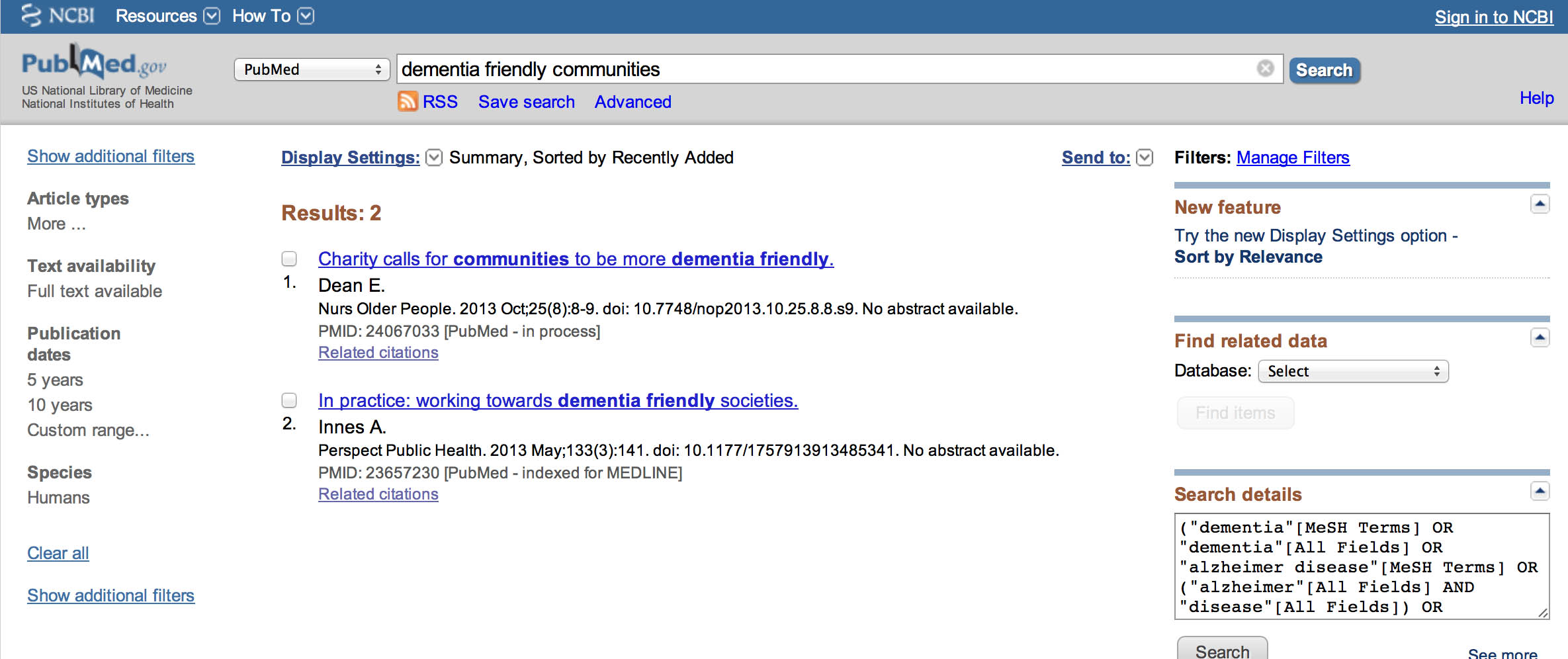

It’s interesting to try to identify where the ‘barriers to communication’ are. The media’s role in the public understanding of science has been much criticised by scientists, but it could be the case that bad dancers are in fact blaming the floor. But likewise it is perfectly possible that people ‘controlling the message’, i.e. journalists, have exerted a disproportionate top down control on what the message is. I suspect that this is precisely what has happened in the case of ‘dementia friendly communities’, where the mainstream media are used to dealing with well resourced communications departments of large charities. Nonetheless, blogs and microblogs such as Twitter have been invaluable in democratising the message.

Examinations of the professional and social forces at work reveal a high degree of collaboration and mutual reliance between scientists and journalists, even though the differences between journalistic and scientific practices can sometimes lead to unbearable disputes. The media do provide the forum in which the relationship between science and the public is pursued, and it is in this forum that the public make moral judgments about science. For example, there has recently be a tsunami of opinion pieces as to whether you’d like to have a blood test which could predict with certain accuracy your chances of developing a dementia (even though the original paper in Nature Medicine was about something rather different.)

However, despite the media’s activity in the communication of science, they have no brief or responsibility for improving the public understanding of science, and in some cases are not particularly well suited to the task. Science writers rarely ‘bend’ articles to get space in their paper, but they may emphasise aspects or use language that gives scientists the creeps. For example, the number of ‘breakthroughs which stop dementia in its tracks’ have recently been endless. These articles can often be irrelevant to most people currently living with early dementia. And yet persons with early dementia would benefit enormously from accurate information about the science of dementia?

In my opinion, there is a serious democratic deficit which could emerge between persons with dementia and researchers. I’ve heard first-hand of medical doctors not explaining the diagnosis of dementia to their patients, instead preferring to give them an ‘information pack’. Likewise, academic researchers seem all too keen to sign up persons with dementia to various research studies, without even writing to them stating the findings from the very same studies.

Human behaviour, to state the obvious, is going to be at heart of engaging any citizen. A strand of modern thinking in “citizen-centric politics” can be traced to political thinking in the wake of the Second World War—notably Hannah Arendt’s “The Human Condition” (1958). Arendt pursued a strong version of political engagement which she considered to be a profound cultural achievement rather than something emerging naturally from human nature. She regarded “citizenship” as a distinctive and consciously adopted role, played out by citizens interacting and debating in a discrete public realm in which everything “can be seen and heard by everybody and has the widest possible publicity”. These days, a public interactive website would suit that function well. It could serve as a platform with some immediacy in providing learning resources explaining in a suitable way for people with dementia with neurocognitive needs what the common dementias are, and how they typically affect thinking. If this were coupled with a blog or Twitter, the end result of a social movement could be very powerful indeed.

The concept of building a ‘communicative power’ for persons with early dementia

Some argue that ‘communicative power’ lies at the heart of the communication model of the political process. Habermas borrows the concept of communicative power from Hannah Arendt, while somewhat reformulating it. Arendt emphasises that power is always something exercised in common, not by an individual: power corresponds to the human ability not just to act but to act in concert.

During the last few decades of the 20th century, the debate on citizens’ participation in their own governance has tended to move away from the Arendtian constraints towards exploring and applying more fluid and nuanced approaches. The German critical theorist Jürgen Habermas proved a seminal influence on the debate, arguing for what he termed ‘communicative rationality’, whereby competent and knowledgeable citizens engage with one another in good faith, and through the giving (or assuming) of reasons arrive at a shared understanding about a situation.

“insofar as the democratic process, as it is institutionally organised and conducted, warrants the presumption that outcomes are reasonable products of a sufficiently inclusive deliberative process”

How can we bring about a sustainable authentic ‘behavioural change’ in allowing persons with dementia to lead in dementia friendly communities?

Nudge has clearly had its limitations, which is why the RSA has developed “Steer” through the “Social Brain” project. Drawing on a range of research from several disciplines, Steer enables people to appraise situations and make judgments about when they should trust, or be wary of, their gut instincts, rational convictions or environmental influences. The full rationale of the RSA’s articulation of “Steer” is provided in Grist (2010).

It is always extremely exciting when there is original evidence of behavioural change taking the debate forward. For example, the RSA recently a conducted a study entitled “Cabbies, Costs and Climate Change” (2011). The recommendations arising from the project as a whole are outlined in detail in their final report. They include making habitual behaviour (rather than just behaviour) the focus of interventions, making fuel efficiency a pass/fail criterion on the driving test, changing driving habitats to encourage fuel efficiency, incentivising taxi drivers to become ambassadors for fuel efficiency, providing more salient feedback, and making taxis greener.

This is an example of a beneficial behavioural change. Could such a behavioural change be effected for persons living with an early dementia?

It has previously been reported that people living with dementia face psychological and emotional barriers to being able to do more in their community, alongside physical issues. These common barriers are said to include a lack of confidence, being worried about getting lost, mobility issues and physical health issues, and not wanting to be a burden to others. It is therefore odd that there has been given such scant regard to electronic dementia-friendly communities – indeed communities run mainly by and for persons with early dementia.

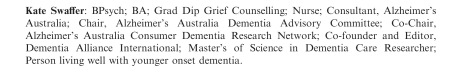

For example, in the voluminous Alzheimer’s Society report “Building dementia friendly communities: a priority for everyone”, the definition of community is strikingly narrow.

“The term ‘community’, within this report, relates to the area in which people live, including the shops and cafes they visit, the places they enjoy for recreation or leisure and the wider public spaces that surround them. It can be described as the various interfaces and interactions that a person with dementia and their carers require in their locality in order to live well.”

However, the definition provided by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in its seminal report “Creating a dementia friendly York” is considerably wider, and includes the term ‘social networks’.

“A dementia-friendly community has been described by people with dementia in this project and in others to which we have contributed as one that enables them to:

• find their way around and feel safe in their locality, community or city

• access the local facilities that they are used to (such as banks, shops,

cafés, cinemas and post offices, as well as health and social care services)

• maintain the social networks that make them feel still part of their community.”

The tone of their report is altogether different. Instead of involving people with dementia, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation talk about people with dementia “at the heart of the process”. They frame the components of their dementia friendly communities using ‘The Four Cornerstones Model’ construct.

“With the voices of people at the heart of the process, we believe that communities need to consider four ‘cornerstones’ to test the extent of their dementia friendliness.

These are:

Place – how do the physical environment, housing, neighbourhood and transport support people with dementia?

People – how do carers, families, friends, neighbours, health and social care professionals (especially GPs) and the wider community respond to and support people with dementia?

Resources – are there sufficient services and facilities for people with dementia and are these appropriate to their needs and supportive of their capabilities? How well can people use the ordinary resources of the community?

Networks – do those who support people with dementia communicate, collaborate and plan together sufficiently well to provide the best support and to use people’s own ‘assets’ well?

Collective endeavours need coordination and mutual understanding, which often takes time, effort, and experience to establish.

And yet collective decision-making is central to the wellbeing communities, towns, and city neighbourhoods. This painstaking and often divisive civic process can be especially difficult for the many towns, counties and rural areas that have little or no coverage in print media, such as a local newspaper. There is little reason to believe to think collective decision-making would fail in a supportive electronic environment such as a Wiki, for persons with early dementia.

The power of the internet and solidarity

Imagine life without the technologies many rely on every day: the computer, smartphone, #ipad, or similar. In many western cultures, we have grown so accustomed to the use of these tools for communication, discourse, and social activities that it is hard to envision us without them. By collaborating in social networks, computer users around the globe now contribute to a new way of learning. This learning allows reshaping of knowledge, information, and culture, and informs how we create and share content “between individuals, groups, and societies”.

Solidarity is a key aspect of such collaborative networks.

As the RSA point out in the report “Beyond the Big Society – Psychological foundations of active citizenship”, ‘solidarity’ is a hugely complex notion, and there is a large literature on the subject. However, the authors conclude that it is broadly about integration, about the extent to which we feel we are on ‘common ground’ with and have a sense of mutual commitment with the people with whom we share space, time and resources.

As Sarah Ammed puts it:

“Solidarity does not assume that our struggles are the same struggles, or that our pain is the same pain, or that our hope is for the same future. Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, we do live on common ground. While statistics on community cohesion (social solidarity between different cultural groups) in the UK suggest some progress in developing solidarity in our most culturally and ethnically diverse places, this progress occurred in conjunction with more than a decade of strong and sustained economic growth, low unemployment and massive investment in public services. Community cohesion could easily become a hot political and social issue as the cuts to public spending begin to bite, and competition for services and resources intensifies. For the Big Society to flourish, policymakers will need to work very hard to better understand and help develop new ways of strengthening social solidarity, particularly in our most culturally and ethnically diverse communities, where levels of social solidarity tend to be lowest and levels of multiple deprivation and social exclusion tend to be highest.”

The need for further exploratory research for the implementation of Steer: persons with early dementia

There is clearly a need to look at how the principles of ‘Steer’ could facilitate collective decision making in persons with early dementia. As part of the exploratory research, a structure as successfully implemented in research for police officers as reported in 2012 could be utilised.

Persons with early dementia will be able to produce a range of opinions as to work best for them, and it is possible that some views might fractionate according to a precise cognitive diagnosis. But that’s where the medicalisation ends. The impetus behind asking persons with dementia what they feel in relation to the world around them is a necessarily unique experience.

We could begin the process if people with early dementia decided to engage with a website providing information about dementia pitched suitably at them, making reasonable adjustments for their abilities. We could then begin to explore whether and how the principle of RSA’s “Steer approach” to behaviour might be applied in communities for people living with an early dementia.

We could then invite a larger number of people with early dementia to participate in a series of two face-face deliberative workshops. The intention was to explore Steer principles with participants, who would then experiment with applying them, and keeping diaries of their experiences, before sharing and examining these in a second workshop. This way, we could produce a rich corpus of data, which gave considerable insight into the challenges facing police and the ways in which RSA’s engaged approach to behaviour change might be able to help them better rise to these challenges.

Persons with early dementia are an important section of the public with whom we should engage over the science of dementia

It’s clearly critical for us as a society to evaluate critically, question and debate in a focused way the key issues in science and society. A large number of people in the public live successfully with an early dementia. Finding ways to illustrate the Steer principles in relation to dementia, including film-making, theatre productions, exhibitions, discussion and policy-influencing events and multimedia, could be hugely exciting.

As well as a societal and moral drive for the need to discuss the science of dementia with people with dementia, there is also potentially a legal imperative.

A “mental health condition” is considered a disability if it has a long-term effect on your normal day-to-day activity. This is defined under the Equality Act 2010. Your condition is ‘long term’ if it lasts, or is likely to last, 12 months, and ‘normal day-to-day activity’ is defined as something you do regularly in a normal day. There are many different types of mental health condition which can lead to a disability, legally; and dementia can be one of them.

There is no justification for people with dementia to be treated in an inferior way to people without, hence the purpose of the discrimination legislation in England and Wales. It’s important to appreciate that for the greatest part of our history, the political, social and economic life of most societies were controlled by a single nobility “held in place.” Those outside the elite who questioned this monopoly on power would suffer various unpleasant penalties. On the other hand, creativity is essential to change our society for the better. And, in fact, there is a large body of evidence to highlight that persons with dementia can be incredibly creative, But, if we, as a society, only tap into an elitist pool of creativity then we impede our own ability to tackle the myriad of problems we face. Politics, sadly, is the very opposite of creativity. Politics, as it is currently conceived, is inherently elitist, and corporate-like charities may have agendas with politicians which are consequently at odds with the persons with dementia they appear to seek to involve.

Conclusion: a ‘power to create’ something unique

In relation to the strong ethos of ‘power to create’, which many argue William Shipley, founder of the RSA, would have signed up to, Anthony Painter covers this beautifully in his blogpost “We need to talk about power” from 8 January 2014:

“Morozov argues that the nature of political community matters. The institutional structure matters if you want the power to create to be really dispersed rather than concentrated. That’s why we need to talk about power, its form, the ethos that seeks to deploy it, and its purpose: our purpose as individuals who wish, need, and should create.”

I feel passionately a power to create a medium in which persons with early dementia can think about their own Self, based on a genuine engagement with individuals over the current neuroscience of dementia, will be a critical start. I think, armed with this knowledge, people can be armed with the tools as to how best to go about making decisions.

This is as much as giving persons with dementia “a voice”, in as much as befriending them in large numbers important though that is. The ‘communicative power’ of an electronic website, providing resources on the neuroscience of dementia and tools for people with dementia to engage with ‘Steer’, I think could bring about an important behavioural change in not just ‘involving’ people with early dementia – but also making sure they ultimately lead in their own communities.

References

Alzheimer’s Society (2013) Building dementia friendly communities: a priority for everyone.

Arendt, H. (1958) The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press: Illinois, p. 50.

Ballenger, J.F. (2006) Self, senility, and Alzheimer’s disease in modern America: A history. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Clare, L. (2003) Managing threats to self: Awareness in early stage Alzheimer’s disease, Social Science & Medicine, 57, pp. 1017–1029.

Dworkin, R. (1986). Autonomy and the demented self, The Milbank Quarterly, 64(2), pp. 4–16.

Grist, M. (2010) Steer: Mastering our Behaviour through Instinct, Environment and Reason, RSA: London.

Habermas, J. (1984) (translated McCarthy, T.), The Theory of Communicative Action, Beacon Press: Boston, 1984.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2012) Creating a dementia-friendly York. Accessible at: http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/dementia-communities-york-full.pdf (viewed 15 March 2014).

Portacolone, E., Berridge C., Johnson, K, Schicktanz, S. (2014) Time to reinvent the science of dementia: the need for care and social integration, Aging Ment Health, 18(3), pp. 269-75.

London Arts and Health Forum. (2014) Connected Compassionate Communities: An Action Research Project, West Midlands – deadline 13 July. Accessible at: http://www.lahf.org.uk/connected-compassionate-communities-action-research-project-west-midlands-deadline-13-july (viewed 15 March 2014).

Painter, P. (2014) Blogpost: “We need to talk about power” Accessible at: http://www.rsablogs.org.uk/2014/enterprise/talk-power/ (viewed 15 March 2014).

Peña-Casanova J1, Sánchez-Benavides G, de Sola S, Manero-Borrás RM, Casals-Coll M. (2012) Neuropsychology of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Res, 43(8), pp. 686-93.

Roberts, C. (2014) Blogpost: “Immediate day care rant”vAccessible at: http://mason4233.wordpress.com/2014/03/08/intermediate-day-care-rant/ (viewed 15 March 2014).

Rowson, J., Lindley, E. (2012) RSA Projects: reflexive coppers: adaptive challenges in policing, RSA: London.

Rowson, J, McGilchrist, I. (2013) RSA Projects: Divided brain, divided world, RSA: London.

Rowson, J, Young, J. (2011) RSA Projects: Cabbies Costs and Climate Change, RSA: London.

Rowson, J, Mezey, M.K., Dellot, B. (2012) RSA Projects: Beyond the Big Society – Psychological foundations of active citizenship, RSA: London.

Saunders, P. A. (1998) ‘‘My brain’s on strike’’: the construction of identity through memory accounts by dementia patients, Research on Aging, 20(1), 65–90.

Swaffer, K. (2014) Re-investing in life after a diagnosis of dementia. Accessible at: http://kateswaffer.com/2014/01/20/re-investing-in-life-after-a-diagnosis-of-dementia/ (viewed 15 March 2014).

Thaler, Richard H.; Sunstein, Cass R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Yale University Press.

Tourage, M. (2007). Rumi and the hermeneutics of eroticism. Leiden, The Netherlands: BRILL. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004163539.i-260.

UK Government. When a mental health condition becomes a disability Accessible at: https://www.gov.uk/when-mental-health-condition-becomes-disability (viewed 15 March 2014).

Wellcome Trust website. Public engagement Accessible at: http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/funding/public-engagement/ (viewed 15 March 2014).