“What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet”

Act II Scene 2 Romeo and Juliet William Shakespeare

“Their families and partners are also told they will have to give up work soon to become full time ’carers’. Considering residential care facilities is also suggested.”

“All of this advice is well-meaning, but based on a lack of education, and myths about how people can live with dementia. This sets us all up to live a life without hope or any sense of a future, and destroys our sense of future well being; it can mean even the person with dementia behaves like a victim, and many times their care partner as a martyr.”

“Labelling” as a sociological construct has been used to inform medical practice, since the 1960s in order to draw attention to the view that the experience of ‘being sick’ has both social as well as physical consequences.

Becker’s (1963) original work on the social basis of deviance argues that, ‘social groups create deviance by making the rules whose infraction constitutes deviance’.

Applying these ‘rules of deviance’ to individuals or groups means labelling them as ‘outsiders’. He goes on to argue that, ‘deviance is not a quality that lies in the behaviour itself, but in the interaction between the person who commits an act and those that respond to it’.

Goffman’s (1968) work is less concerned with the social process of labelling a particular action or pathological state as deviant, than with the stigmatising consequences of that process for an individual – what he referred to as ‘The management of everyday life’.

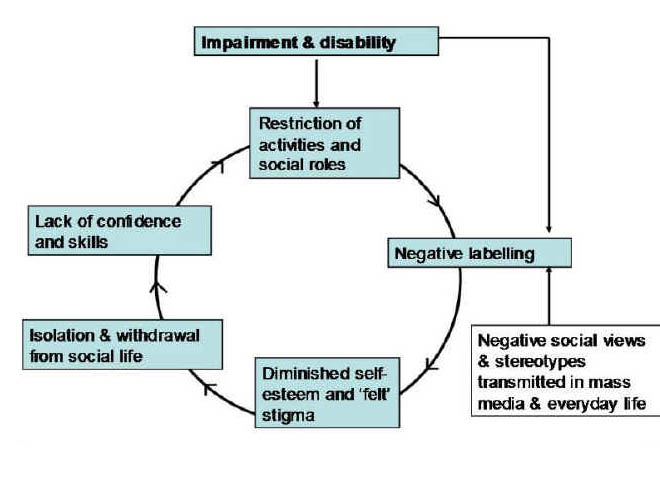

Various theories have led to a concept of a ‘stigma cycle’ [as depicted, for example, in Taylor and Field (2007)]:

I remember when an able-bdied leftie went on a diatribe on a private thread concerning how “the disabled” had been treated. Being physically disabled, however, I really got a feeling of she was talking on behalf of “us” as one large homogeneous group. I felt offended. I blocked her. I concede readily now this was a complete over-reaction.

But there’s no point being prissy or being overly-PC?

Indeed, it is said that the “dementia friendly communities” programme focuses on improving the inclusion and quality of life of people with dementia.

But using a label “dementia”, which in fairness is a commonly used term (and a medical diagnosis), runs the risk of eliminating diversity in a range of cognitive abilities.

The abbreviated Mini-Mental State Examination (1974) is the widely used ‘screening’ test for dementias, particularly those which load heavily on a memory component such as Alzheimer’s disease.

It is marked out of a maximum of 30, and a “low but normal” score is considered about 24, some feel.

And not all dementias are to do with memory problems. However, it might be more pragmatic, and potentially less stigmatic, to identify particular symptoms with which initiatives could be desired:

@legalaware @shirleyayres @julianstodd cold they be memory friendly networks? Never like defining ppl by diagnosis

— Alastair Somerville (@Acuity_Design) March 18, 2014

but one person’s problem with spatial navigation could be another person’s problem with memory… and so it goes on.

A problem here is that people who currently are ‘living well’ might resent ‘special treatment'; but the aim with equality and parity initiatives generally is to ensure that certain people are not disadvantaged and simply put on an equal footing.

In recent years, the Greek term ‘‘stigma’’ has emerged from this same risk paradigm to describe certain products, places, or technologies marked as undesirable and therefore shunned or avoided, often at high economic, social, and personal costs.

Traditionally, both distrust and avoidance of risk have been found to be more common among disenfranchised groups.

However, most people would agree that a cynical use of the ‘dementia friendly communities’ as merely a kitemark to secure business advantage, even if it encourages corporates to participate, is suboptimal.

The neighbourhood-centered definition of community still makes partial sense, even in these days of global Internet connectivity.

According to Barry Wellman, professor of sociology and the director of NetLab at the University of Toronto, once people stop seeing the same villagers every day, their communities are not groups but social networks.

“Most members of a person’s community are not directly connected with each other, but are sparsely knit, specialized in role, varying in connectivity, and unbounded (like the Internet). Like the Internet, they are best characterized as a “network of networks”.”

Wellman further argues, “In such a world, social networking literacy is as vital as computer networking literacy for creating, sustaining, and using relationships, including friends of friends. ”

And the ‘networks’ angle plugs neatly into the policy drive for technological innovations for dementia.

@legalaware @julianstodd I agree interesting to see how apps like @Streetclub @streetlife_uk & @SocialMirrorApp are connecting communities

— Shirley Ayres (@shirleyayres) March 18, 2014

Alzheimer’s Australia instead prefers the term “Dementia friendly societies”, which makes one wonder whether there’s an enormous important difference between community and society.

“Dementia friendly societies has been defined in a number of different ways; … we will be using the definition proposed by Davis et al. – a “cohesive system of support that recognises the experiences of the person with dementia and best provides assistance for the person to remain engaged in everyday life in a meaningful way”. ”

And indeed social cohesiveness has come from a number of different converging arms of evidence.

It was in recognition of the importance of community participation that the 2000 NHS Plan described a new vision for the English NHS in which “the service user is centrally placed and is required to be consulted on all matters of policy and service development”

Furthermore, in order to move beyond the ‘tokenism’ levels of participation and begin to achieve genuine citizen power, it was discussed that “users” need to feel empowered and as such have the ability and opportunity to shape the methods used for their involvement.

But inevitably issues about the name of this policy, while clearly well meant, revert to a discussion of stigma.

It is said that ‘a cure for dementia’ would be an important societal breakthrough as was the drive for a treatment for HIV/AIDS.

Stigma had stood out as a major barrier to HIV prevention and treatment services in Nigeria.A fear of different types of stigma that stand as barriers to access.

But a key lesson here was that a number of different stigmas were described in addition to community stigma – for example, self stigma, familial stigma, institutional stigma and organisational stigma surfaced as issues that influence access.

Whilst much of this analysis is clearly an academic one, whether the term itself ‘dementia friendly communities’ itself exacerbates or diminishes division in a ‘them against us’ way is worthy of some scrutiny. For what it’s worth, ‘dementia awareness’ is difficult to argue against, as it is motherhood and apple pie stuff, but whether people have an accurate working knowledge of what the dementias are, and what can be done for people with dementia, as a result of this policy is an altogether different issue. I am not so convinced about this – nor who the exact beneficiaries have been.