Whether or not interventions and initiatives are worthwhile demands long term scrutiny. This is to make sure that initiatives such as ‘Dementia Friends‘, the provision of mass information sessions for the public on some basics about dementia, or accreditation schemes for dementia friendly communities aren’t done, ‘signed off’, and silently disposed of when it’s unclear what the outcomes have been.

It’s always been said that “Dementia Friends”, not ‘training’ but provision of information about dementia, unsuitable for anything higher than tier 1 (in comparison specialist healthcare staff might be trained to tier 3), is a ‘social movement’ “turning communication to action”. In other words, armed with your new knowledge of dementia, you might do something constructive in response.

I have never convinced of a reason for this programme, say, is in improved detection by you of someone slow with their change ahead of you in a shopping queue because of dementia. In fact, getting frustrated at an old person in front of you due to slowness in counting change might be a phenotype of outright ageism, irrespective of the presence of dementia, or simply bad manners. There has been an issue of how the programme might encourage you to behave a certain way towards ‘a person with dementia’. But that is to assume you can identify a person with dementia as if they were wearing a sticker on their forehead with the word “DEMENTIA” in big letters. Many disabilities, including dementia, are indeed invisible. This is akin to not judging a person as ‘normal’ who happens to have an indwelling catheter due to continence issues in multiple sclerosis.

The late Conservative health minister, J. Enoch Powell, famous for various other things too, always warned against the ‘numbers game’. In a break-out session for the Alzheimers Disease International conference yesterday, four speakers from four jurisdictions, including England, Japan, India and Australia, described their perception of what a ‘dementia friendly community’ might be. Kate Swaffer, Chair of Dementia Alliance International, emphasised how such a community should be seen as enabling and inclusive, citing Kiama as an example of good practice.

But other jurisdictions clearly lapsed into “the numbers game” – Japan cited a growing number of ‘dementia caravan volunteers’. the state of Kerala in India offered 100,000 “dementia volunteers”, and Jeremy Hughes, CEO of the Alzheimer’s Society, cited how the Dementia Friends “With a little help from your friends”, slickly produced by professionals, had garnered over a half of million ‘hits’ on YouTube.

Particularly having met Gina at the Alzheimer’s Society conference in London last year, I can say I love the Dementia Friends video as a creative pitch.

But there is a moral imperative to see what these dementia programmes are doing, not least because the substantial cost of a public backed initiative might be at an opportunity cost to other equally meritorious approaches, such as improving rehabilitation services for dementia. Also, there is a fundamental wish, surely, to know whether the initiative has met any of its original ambitions.

The original English dementia strategy, “Living well with dementia”, was supposed to last five years, and indeed did so from 2009. There was never a renewal of this strategy. There was instead an overwhelmingly underwhelming ‘implementation plan’ for ‘Dementia 2020′ from the Department of Health, which did not address the Baroness Greengross’ stated wish to log the ‘lessons learnt’ from the successes and failures of the original strategy.

In this strategy, it was clearly stated that English dementia policy had to prioritise mitigation against stigma and prejudice towards dementia. Of course, there can be ‘unintended consequences’ of so-called ‘dementia awareness’ – a substantial number believe that queuing in a shopping queue called ‘dementia friendly checkout’ or parking in a ‘dementia friendly car parking space’ in fact markedly exacerbates stigma, and is potentially quite offensive.

Even a badge, rather than encouraging inclusion, can impose an unintended ‘them and us’ distinction.

So the idea of “Dementia Friends”, or any other jurisdictional attempts to emulate this, being a ‘social movement’ is deserving of scrutiny, and should not glibly assumed.

Consider this. Say there are 2 million people who go out each to buy a Mars Bar, a homogeneous product, following an intense publicly funding marketing campaign set up by top quality marketing agencies. Could be said that 2 million purchases of Mars Bars was a social movement of Mars Bar friends – or simply an anticipated benefit of a mass marketing ‘top down’ broad sweep campaign?

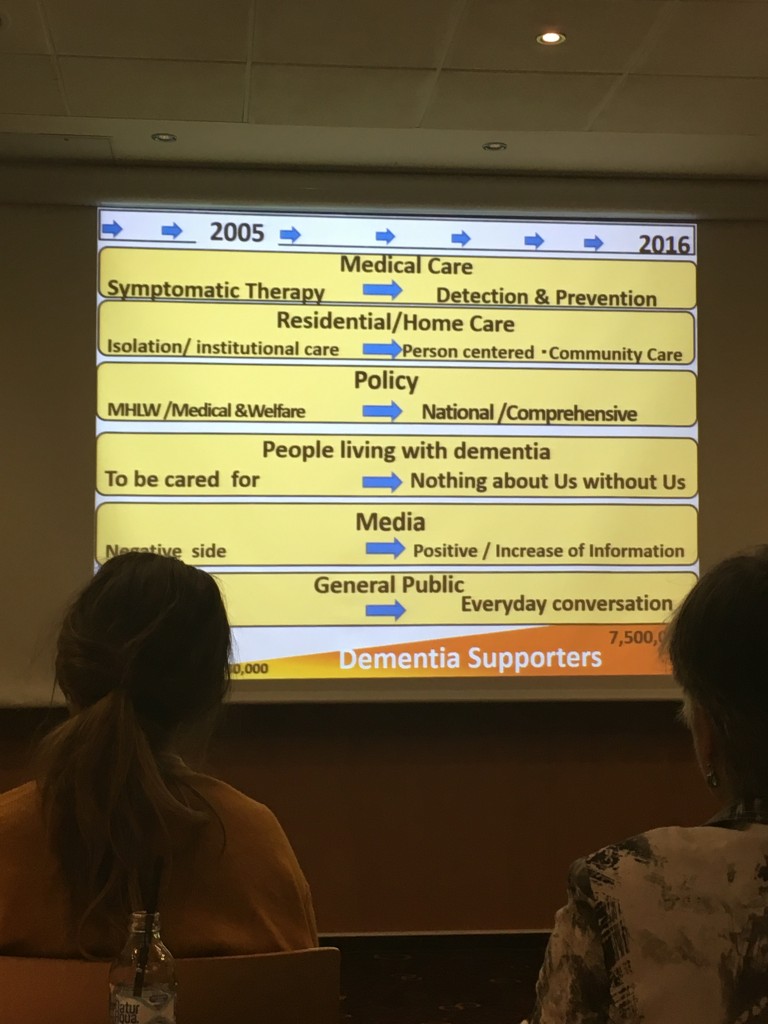

The talks from the other jurisdictions indeed touched upon what might have been reasonable outcomes.

Say, for example, in Japan.

And indeed there are a number of possible ways in which you could consider ‘Dementia Friends’ has been of benefit.

These might conceivably include:

- reduction of stigma and prejudice in public perceptions

- better knowledge of dementia and how dementia impacts on personal lives

- uptake of ‘dementia friendly initiatives’ in quality of care, such as ‘dementia friendly hospital wards’

- better ‘customer experience’ from high street businesses or corporates

- better perceived ‘quality of life’ of people living with dementia and those closest to them

- better awareness of possible symptoms of dementia thus promoting more timely diagnosis of dementia

- increased confidence of people with dementia living independently (not in isolation) in the community.

It is not fair and appropriate to reduce this into two or three questions, say “how much more confident do you feel about dementia?”. People invariably don’t know the sample size, or any other thing about basic demographics of the sample.

I have noticed a huge drive in Dementia Friends, and in fairness other jurisdictions too, to play ‘the numbers game’. So, at first, you are seeking one million friends – and then you can make the website deliver more friends more easily – so the number increases for little further effort. But this is being accompanied by a marked shift in societal attitudes in dementia? It’s like my mass marketing of Mars Bars analogies.

A social movement for me also implies that the people delivering the information session have some intellectual investment in the process. This is not true of Dementia Friends, which specifically wants Dementia Friends Champions to deliver the same product as advertised – as indeed a Big Mac is the same whether you buy it in Doncaster or Dubai. The organisers of Dementia Friends clearly do not want Mars Bars accidentally turning into Snickers, by the addition of a few peanuts, by a few ‘rogue champions’.

One or two companies delivering a ‘better customer experience’ will be an expected outcome from those companies which have invested money in such a programme. The issue is whether this is replicable through means such as ‘secret shoppers’.

So, all in all, it is of vital importance how you actually measure the efficacy of the social movement. I indeed asked this as a general discussion point in the session chaired by Glenn Rees, the Chair of Alzheimer’s Disease International.

And of course there are a number of ways to tackle this question.

Jeremy Hughes mooted the idea of high quality survey data. I think this would be far superior to relying on a quantitative analysis of pledges from the pledge card. For a start, there is a problem with potentially low response rates for pledge cards. Secondly, whilst easy to codify, the information from the pledge cards are only as good as the quality of the pledges you can pick from in a multiple-choice fashion. For example, in my experience as a Dementia Friends Champion, I have learnt that many people want to ‘join dementia research’, as it gives them some agency and hope about dementia. And yet this is not a stated pledge. It does concern me how slow Dementia Friends has seen to be in working with NIHR in fostering links between the ‘Dementia Friends’ and ‘Join Dementia Research‘ initiatives?

Formal assessments do of course exist of the ‘success’ of social movements. But for the reasons I describe above actually identifying the outcome measures is itself tricky.

Take for example the ‘social value return on investment’ (SROI).

The key assumption of SROI analysis is that there is more to value creation than purely economic value, indeed the value creation process can be thought of as a continuum with purely economic value at one end, through to socio-economic somewhere in the middle, and social value at the other end. Economic value creation is the raison d’etre of most for-profit corporations (i.e. taking a product to service to market that has greater value than the original inputs and processes that were required to generate it), whereas social value is created when ‘resources, inputs, processes or policies are combined to generate improvements in the lives of individuals or society as a whole’.

Social value creation is a huge goal for the third sector in facilitating social inclusion and access for those that may be marginalised). However, unlike economic value, social value is difficult to quantify, varies according to the type of organisation involved in its creation and does not have a common unit of analysis (such as money) that enables it to be easily standardised and compared.

The current interest and enthusiasm for measuring social or program impact is not new. The impetus arguably came from the United States, especially from university social work departments and was embraced by both the community sector and government.

Social Movement Impact Theory (otherwise known as Outcome Theory) is a subcategory of social movement theory, and focuses on assessing the impacts that social movements have on society, as well as what factors might have led to those effects. It is relatively new, and was only introduced in 1975 with William Gamson’s book “The Strategy of Social Protest,” followed by Piven and Cloward’s book “Poor People’s Movements”.

Finding appropriate methods to use for studying the impacts of social movements is problematic in many ways, and is generally a large deterrent to scholars to study in the field. The first problem scholars ran into was defining “success” for social movements; the significance of this is that key stakeholders often have disagreements of what a movement’s goals are, and thus come to different conclusions about whether a movement has “succeeded.” Argos might have different outcomes in mind to Addenbrookes Hospital in Cambridge?

Other issues arise when one attempts to locate a movement’s impact in all arenas. Impacts are most often studied at the political level,and yet it has been proven that they have individual, cultural, institutional, and international effects as well. Is exporting an operational homogenous product the same as propagating a wider social movement?

The psychology of the individuals who participate in movements are normally profoundly affected. But do the 1.5 million ‘Dementia Friends’ feel any sense of connectedness to one another? One suspects not, especially if some have achieved ‘Dementia Friends’ status through a few minutes on a computer terminal in isolation.

Has Dementia Friends shifted quality of care or attitudes in care homes, for example? Has it shifted political attitudes to dementia which have historically been shaped by much political lobbying? One parsimoniously thinks not if the current Government wishes to shift emphasis now to diabetes, and has not even renewed post 2014 the English dementia strategy.

Inevitably within government there continues to be an interest in and application of techniques for program or project evaluation such as cost benefit analysis. And this from an utilitarian perspective makes complete sense – in terms of society’s assessment of ‘getting most bang for your buck’.

Lessons for Dementia Friends can also be usefully learnt from other arenas.

For example, an interesting example of an impact evaluation is provided in a report from a few years ago. This report was entitled “An evaluative framework for social, environmental and economic outcomes from community-based energy efficiency and renewable energy projects for Ashton Hayes, Cheshire March 2012″ , and was published from the nef (the new economics foundation).

Ashton Hayes is a rural village located just outside Chester. Their aim is to become the first carbon neutral village in England, through energy efficiency measures and carbon offsetting; by: ‘…encouraging everyone in their community to think about how their way of life affects their impact on climate change and to help people to understand how simple actions can make a big impact on carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere.”

The report helpfully discusses choice of indicators.

It was proposed that all stakeholders are often the best people to identify indicators, but a common mistake is to misinterpret what is meant by ‘measurable’. One should avoid the trap of using inappropriate indicators just because they are readily available; so, if the outcome is important, you will need to find a way to measure it.

Outcomes work also concedes that effect of some outcomes will last longer than others. Some outcomes depend on the activity continuing and some do not. For example, in helping someone to start a business, it is reasonable to expect the business to last for some time after your intervention. The difference between ‘benefits’ and ‘outcomes’ is therefore imperative in this context. The outcomes of a campaign such as ‘Dementia Friends’ will be valid as a snapshot in one particular time.

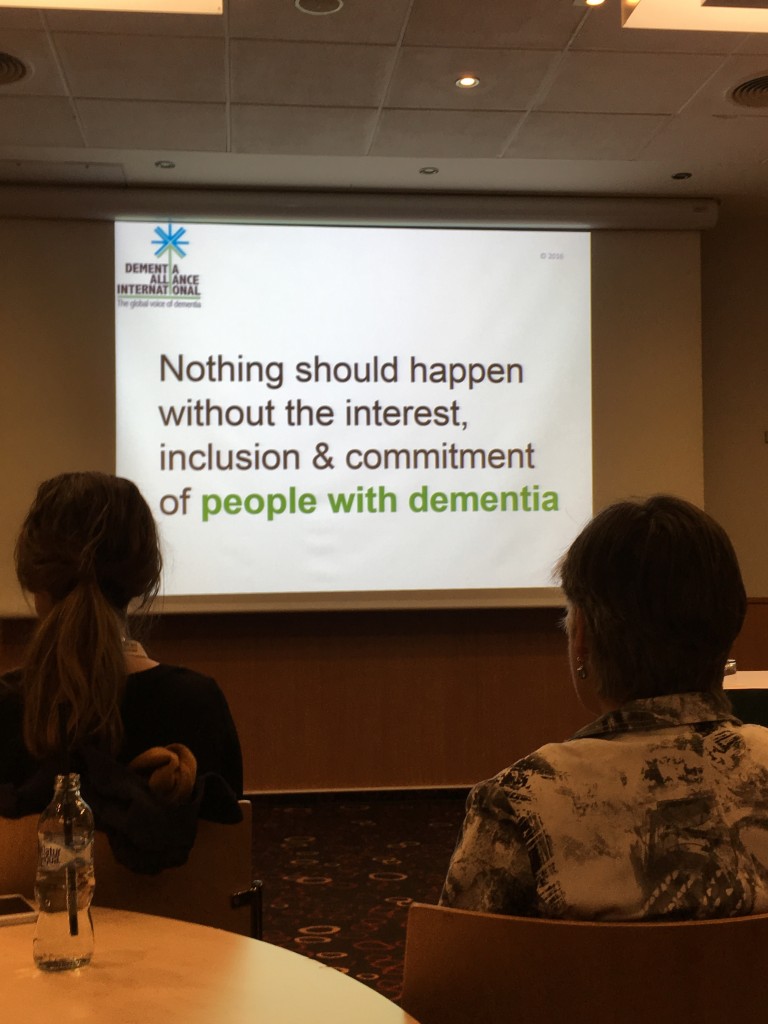

I feel things will change say when people with dementia are genuinely considered as ‘equal and reciprocal partners’ in any relationship. For example, it should be an automatic given that dementia friendly communities include people living with dementia as paid consultants, not tokenistically ‘involved’.

Kate Swaffer successfully conveyed the sentiments behind this for Australia yesterday, for example.

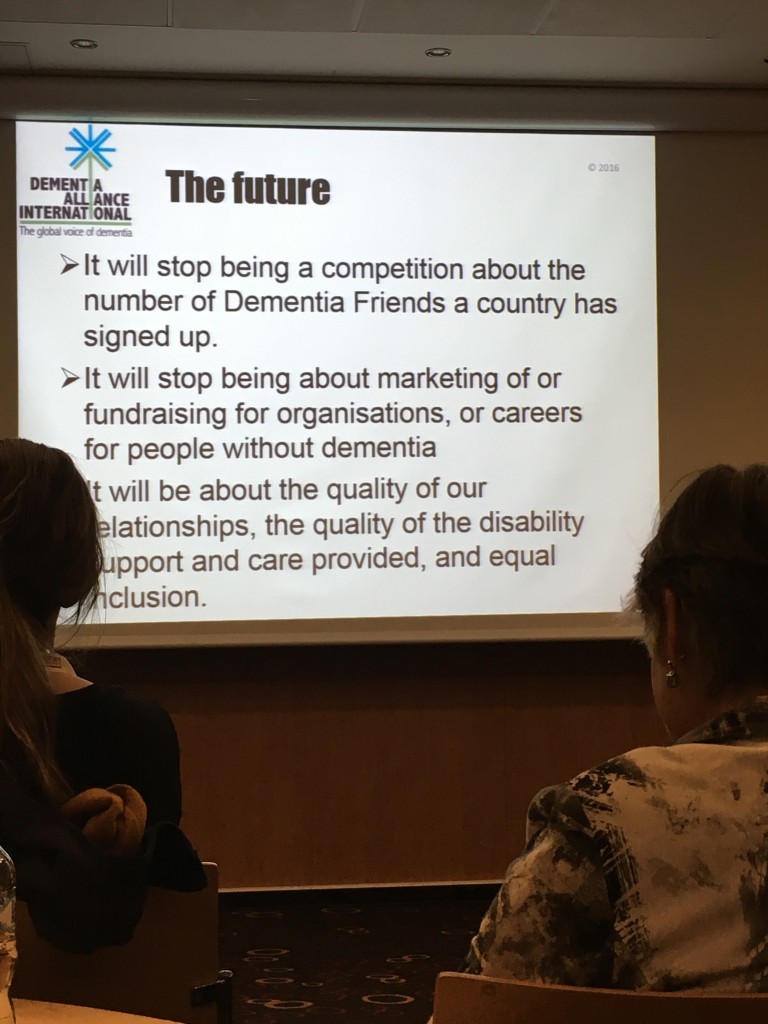

And I think that is the way things are heading now with the Alzheimer’s Disease International umbrella approach of inclusion and a strong ‘rights based approach’, which hopefully will now filter down to national agencies for implementation.

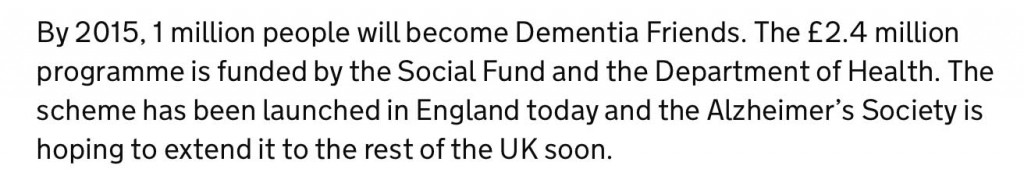

I feel that how ‘successful’ Dementia Friends has been, given the statement below when the initiative was first announced in November 2012, needs to be comprehensively examined.

And ultimately Dementia Friends has to be much more than a successful, easily exportable, marketing campaign – it needs to deliver results on the ground. This is no different for the Alzheimer’s Society and the Government as it is for small social enterprises. The rules of the game must be equally applicable to all, otherwise it’s an “unfair market”.

Dementia enabling communities primarily needs to be for the benefit of people living with dementia and their closest.

Kate Swaffer put it succinctly as follows.