“Dementia is not just about sitting in a bathroom all day, staring at the walls.”

So speaks Norman McNamara in his recent BBC Devon interview this week.

This may seem like a silly thing to say, but the perception of some of “people living with dementia” can be engulfed with huge assumptions and immense negativity.

The concept of ‘living well with dementia’ has therefore threatened some people’s framing of a person who happens to have one of the hundred or so diagnoses with dementia.

It’s possible memory might not be massively involved for someone who has been diagnosed with a dementia.

Or as “Dementia Friends” put it, “Dementia is not just about memory loss.”

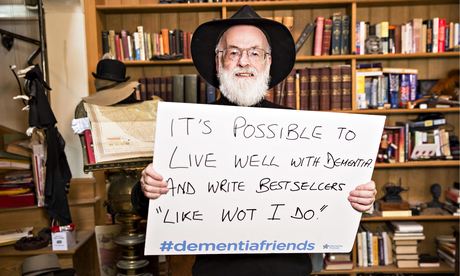

Norman McNamara and Sir Terry Pratchett are people who are testament to this.

“If you made a mistake, would you laugh it off to yourself and say ‘Ha, ha, maybe it’s because I have dementia.””

If somebody else made a mistake, would you laugh at that person and say ‘Ha, ha, maybe it’s because you have dementia.” Definitely not.

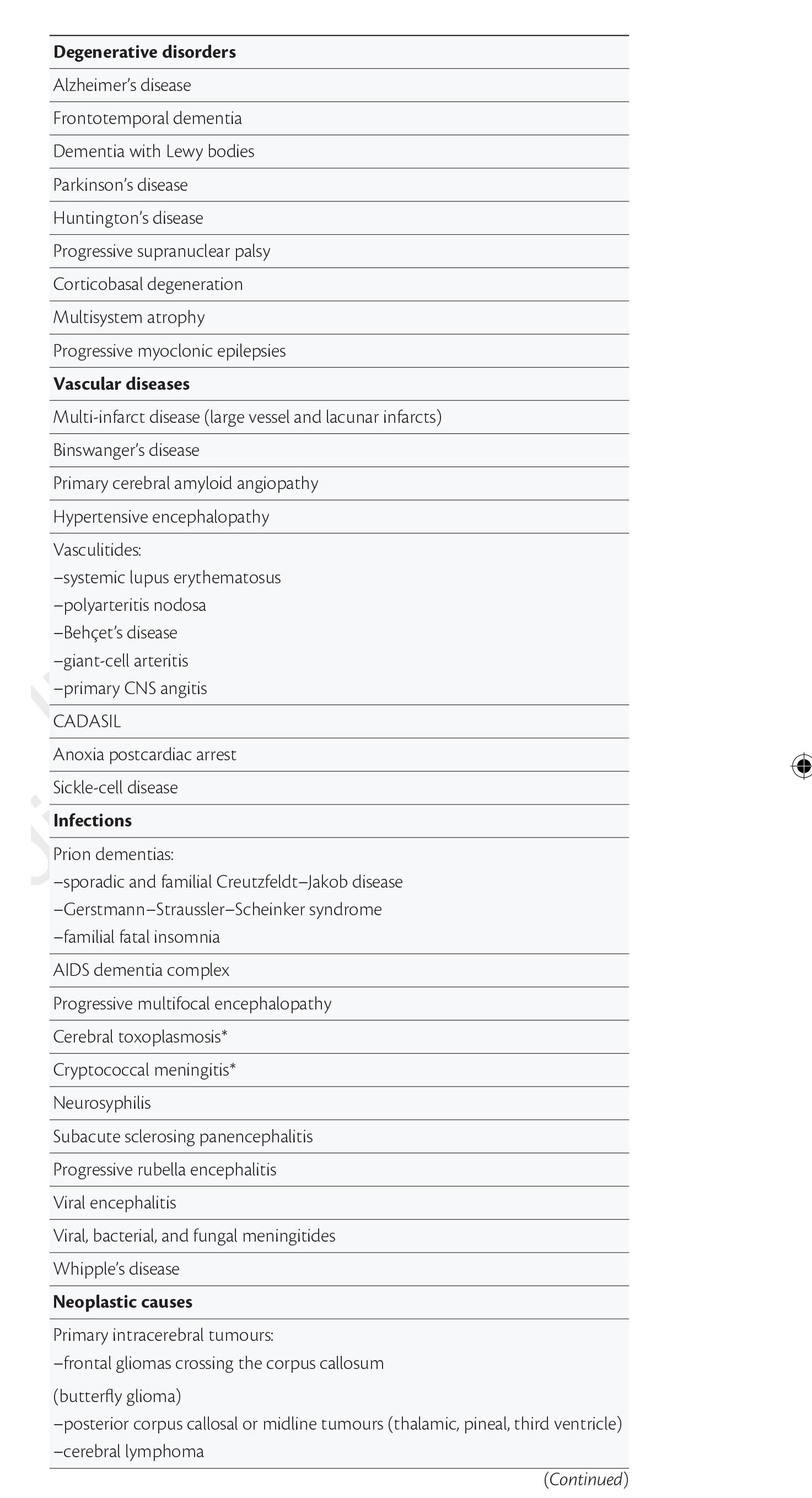

There are about a hundred different underlying causes of dementia.

“Dementia” is as helpful a word as “cancer”, embracing a number of different conditions tending to affect different people of different ages, with some similarities in each condition which part of the brain tend to be affected.

These parts of the brain, tending to be affected, means it can be predicted what a person with a medical type of dementia might experience at some stage.

This can be helpful in that the emergence of such symptoms don’t come as much of a shock to the people living with them.

Elaine, his wife, noticed Norman was doing “weird and wonderful things”.

Norman says “my spatial awareness was awful”, and “I was stumbling and falling”.

Norman, furthermore, was putting “red hot tea in the fridge”, and “shower gel, instead of toothpaste, in [my] mouth”.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia that shares symptoms with both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. It may account for around 10 per cent of all cases of dementia. It is not a rare condition.

It is thought to affect an estimated 1.3 million individuals and their families in the United States.

Problems in recognising 3-D objects, “agnosia”, can happen.

Lewy bodies, named after the doctor who first identified them, are tiny deposits of protein in nerve cells.

See for example this report in this literature.

“Night terrors” have long been recognised in diffuse lewy Body disease.

“The hallucinations are terrific”

The core features tend to be fluctuating levels of ability to think successfully, with pronounced variations in attention and alertness and recurrent complex visual hallucinations, typically well formed and detailed.

See for example this account.

For Norman, it was ‘prevalent in his family’.

Other than age, there are few risk factors (medical, lifestyle or environmental) which are known to increase a person’s chances of developing DLB.

Most people who develop DLB have no clear family history of the disease. A few families do seem to have genetic mutations which are linked to inherited Lewy body disease, but these mutations are very rare.

Monogenetic forms of Lewy body disorders, where a patient inherited the disease from one parent, are rare and comprise about 10% of cases. These familial variants are more common in persons with an earlier age of disease onset.

The patterns of blood flow can help to confirm an underlying diagnosis (see this helpful review).

Also, in this particular ‘type of dementia’, it can be helpful for medical physicians to avoid certain medications (which people with this condition can do very badly with). So therefore while personhood is important here an understanding of medicine is also helpful in avoiding doing harm to a person living with dementia.

However, Norman has been tirelessly campaigning: he, for example, describes how hundreds of businesses in the Torbay-area of Devon have signed up for ‘dementia awareness.”

And, as Norman says, “When you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia.”

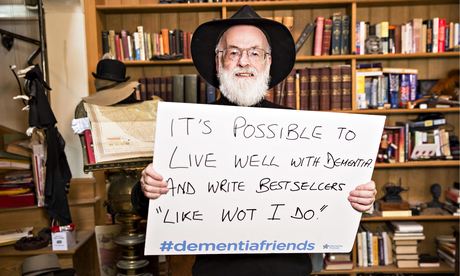

Sir Terry Pratchett is another person living with dementia.

Sir Terry Pratchett described on Tuesday 13th May 2014 the following phenomenon bhe had noticed:

“That nagging voice in their head willing them to understand the difference between a 5p piece and £1 and yet their brain refusing to help them. Or they might lose patience with friends or family, struggling to follow conversations.”

“Astereognosis” is a feature of ‘posterior cortical atrophy’ (“PCA”).

A good review on the condition of PCA is here.

Sir Terry Pratchett has written a personal reflection on society’s response to dementia and his own experience of Alzheimer’s to launch a new blog for Alzheimer’s Research UK: http://www.dementiablog.org

Sir Terry became a patron of Alzheimer’s Research UK in 2008, shortly after announcing his diagnosis with posterior cortical atrophy, a rare variant of Alzheimer’s disease affecting vision.

He went on to make a personal donation of $1 million to the charity, and has subsequently campaigned for greater research funding, including delivering a major petition to No.10 and countless media appearances.

In his inaugural post for the blog, Sir Terry Pratchett writes: “There isn’t one kind of dementia. There aren’t a dozen kinds. There are hundreds of thousands. Each person who lives with one of these diseases will be affected in uniquely destructive ways. I, for one, am the only person suffering from Terry Pratchett’s posterior cortical atrophy which, for some unknown reason, still leaves me able to write – with the help of my computer and friend – bestselling novels.”

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) refers to gradual and progressive degeneration of the outer layer of the brain (the cortex) in the part of the brain located in the back of the head (posterior).

The symptoms of PCA can vary from one person to the next and can change as the condition progresses. The most common symptoms are consistent with damage to the posterior cortex of the brain, an area responsible for processing visual information.

Consistent with this neurological damage are slowly developing difficulties with visual tasks such as reading a line of text, judging distances, and distinguishing between moving objects and stationary objects.

Other issues might be an inability to perceive more than one object at a time, disorientation, and difficulty maneuvering, identifying, and using tools or common objects.

Some persons experience difficulty performing mathematical calculations or spelling, and many people with PCA experience anxiety, possibly because they know something is wrong. In the early stages of PCA, most people do not have markedly reduced memory, but memory can be affected in later stages.

Astereognosis (or tactile agnosia if only one hand is affected) is the inability to identify an object by active touch of the hands without other sensory input.

An individual with astereognosis is unable to identify objects by handling them, despite intact sensation. With the absence of vision (i.e. eyes closed), an individual with astereognosis is unable to identify what is placed in their hand. As opposed to agnosia, when the object is observed visually, one should be able to successfully identify the object.

Living well with dementia means different things to different people.

Pratchett further writes:

“For me, living with posterior cortical atrophy began when I noticed the precision of my touch-typing getting progressively worse and my spelling starting to slip. For an author, what could be worse? And so I sought help, and will always be the loud and proud type to speak my mind and admit I’m having trouble. But there are many people with dementia too worried about failing with simple tasks in public to even step out of the house. I believe this is because simple displays of kindness often elude the best of us in these manic modern days of ours.”

As we better understand what dementia is, our response as a society can be more sophisticated. I’ve found one of the most potent factors for encouraging stigma and discrimination is in fact total ignorance.

Both Norman and Terry demonstrate wonderfully: it’s not what a person cannot do, it’s what they CAN DO, that counts.

This is ‘degree level’ “Dementia Friends” stuff, but I hope you found it interesting.