I must admit that I always feel like throwing something at my computer screen when I see a steering group for people with dementia run by people without dementia but with big financial grants.

For some reason, I used to conceptualise the way some people had approached ‘dementia friendly communities’ like a zoo. Event organisers serially wheeled out a star ‘person with dementia’ like a spectacle, akin to the ‘push me pull you’ of Rex Harrison.

The boot is on the other foot now.

It’s like this.

The thing is communities which are ‘dementia friendly’ should in fact be suitable for all. This means inclusive to all. This means accessible to all.

A major problem with the term ‘dementia friendly’ is that it implies that you can identify immediately person with dementia by the way he or she is behaving in the community. No person with dementia has a sticky adhesive label on his or his forehead saying ‘I have dementia’.

Dementia is an invisible disability. It’s a disability where we can identify the exact problem, say problems with hearing in a noisy room, or problems with memory, or problems reading. Like all disabilities, it requires a sensible approach such as identifying if the problem causes an impairment and subsequent handicap.

I’ve seen this referred to as ‘cognitive ramps’ – but any level of analogy might be suitable such as ‘cognitive wheelchairs’. The basic point is that you’d expect employers to build wheelchair ramps (or simple) for young employees with a physical disability to allow them to get into the building to do their work in the first place; such an attitude is needed for people with young onset dementia too (this is dementia below the age of 65).

The other big way in which the term ‘dementia friendly communities’ is wrong is that it implies a very static process, which ironically is not how the UK accreditation scheme works at all. The UK standards (really specifications) necessitate sustainability, i.e. that the community will be friendly in the future, and is always ‘learning to be friendly’.

This gets to the heart of a tension which exists in policy. That you often hear from many diverse people with dementia that they’re living for the present, and yet there’s one dimension of policy that aspires for a better world for tomorrow – whether this is in the form of dementia friendly communities, or better treatments for the future (disease modifiers or symptomatic treatments).

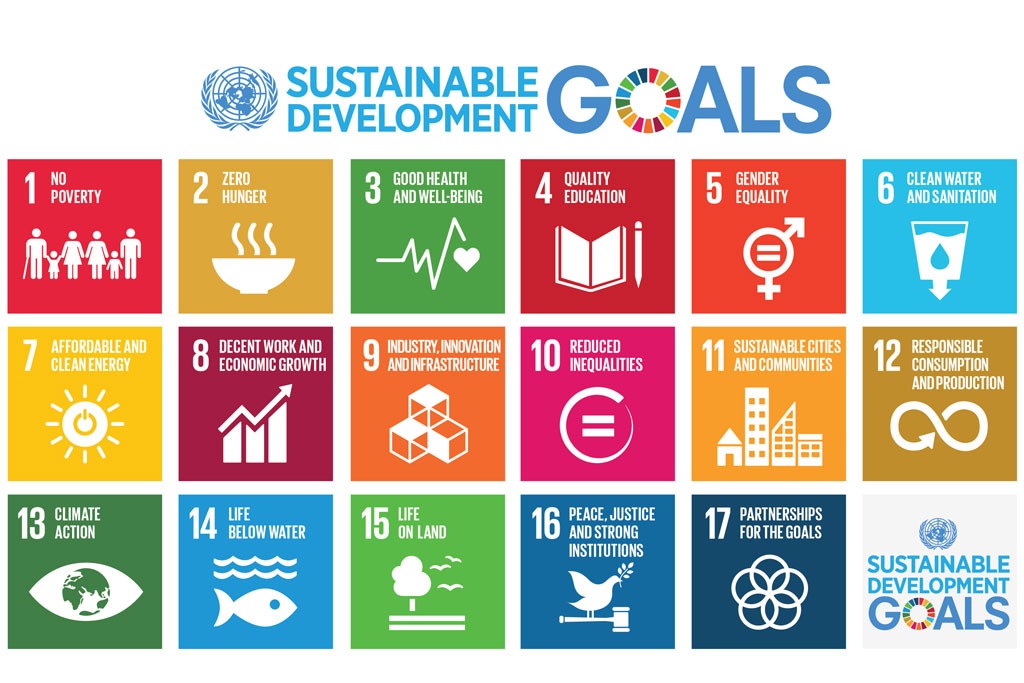

The policy which crystallises the imperative for the world to build ‘dementia friendly communities’ for the future actually comes under the WHO sustainable development goals. They’re pictured here.

It’s clear that people living with dementia need access to the UN Convention on Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD), as all the preamble and articles of that convention apply directly to people with dementia.

Both these instruments are very closely linked to the implementation of a rights-based approach for dementia. Human rights lie at the core of this phase of supporting people with dementia to live in the community after their diagnosis. Even if the UK takes the step of repealing its existing human rights legislation, implementing the European Convention on Human Rights, the global policy tools remain.

The question is of course how people with dementia can best advocate for them. The safest way to make this manageable is to make sure human rights remains in the international conversation, as demonstrated, for example, by Marc Wortmann in the PAHO Plan of Action summit in Washington.

Human rights became serious business when mentioned by Kate Swaffer, Chair of Dementia Alliance International, at the WHO Summit in Geneva last year.

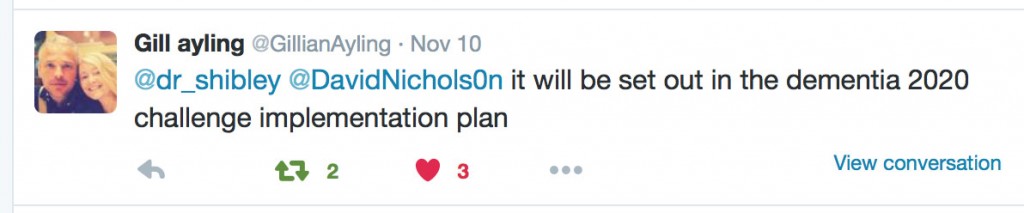

But we do also need local leads which integrate dementia and disability policy drivers together. This, for example, might be facilitated by organisations such as Alzheimer’s Europe participating in the work of the European Disability Forum to make sure that the achievable ‘UN sustainable goals’ and UNCRPD are indeed implemented as ratified. Yesterday, the EPSCO Council adopting the Luxembourg EU Presidency conclusions most helpfully took Europe down the route of rights-based advocacy, as faithfully reported by Alzheimer Europe.

But I feel that we shouldn’t lose sight of the main issue: people with dementia are no longer in the audience. They’re the main actors.