Let me lay my cards on the table: we need now to have a national or even local debate what “post-diagnostic support” for dementia actually means.

This discussion shouldn’t be between the same old same old; we need some fresh faces and fresh voices to help design a system fit for purpose for those who are diagnosed with dementia in England.

So far, there have been in effect two Prime Minister’s Challenges (2012 and 2015) which have highlighted the need for more research, the importance of a timely diagnosis, the essential nature of “post diagnostic support”, raising the profile of dementia with “Dementia Friends”, issues of risk reduction, training and hints at an enhanced rôle of primary care, not just GPs, in offering proactive care and support to promote wellbeing. This was a tall ask.

In March 2015, the Department of Health published ‘The Prime Ministers Challenge on Dementia 2020’ which details the vision for dementia care and support in the future. The document places importance of diagnosis, but also post-diagnosis support and high quality services for people with dementia.

I asked the ‘expert panel’ at the UK Dementia Congress last week in Telford at what dementia policy should be formulated; we’d heard the previous day comments made about approaches at country-wide level, as well as local commissioners making decisions which are best for the local population, as well as personal budgets. The somewhat idealistic objection to personal budgets is that it masks rationing of resources at an individual level, and do not necessarily promote the most clinical effective intervention, at a time when resources have become scarce through deliberate underfunding. I did the personal budgets debate is incredibly complicated, and I reviewed what I could in my current book ‘Living better with dementia: good practice and innovation for the future’.

The truth is : people with dementia are often still sent out in a wilderness following diagnosis, some even lost to follow up in England, and nationally it is estimated one third of people still do not have a diagnosis. There have been even calls for a ‘right to diagnosis’. It is estimated that one quarter of acute hospital beds are occupied by people with dementia, and there is increasing concern in English policy about whether the health and wellbeing needs, met and unmet, of people with dementia and carers are being addressed in the right place and right time.

There’s about 430,000 people living in care homes, and recent studies suggest that 80% of people in care homes have dementia. There is evidence to suggest that prescription of neuroleptic drugs is higher in this group. This is not solely England’s problem, but is an artifact, arguably, of the successful medicalisation and globalisation of a dementia strategy. There is now a huge interest in developing dementia care in post-diagnostic settings, whether at homes or in care homes. I see this work as completely continuous with the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge, and NHS England, CQC and Care England are key players.

The Care Quality Commission published an incredibly influential review of care services ‘Cracks in the Pathway’; that there is more good care than poor care in the care homes and hospitals that their inspectors visited, but that the quality of care for people living with dementia varies greatly. The report found that it is likely that someone living with dementia will experience poor care at some point while living in a care home or being treated in hospital which is unacceptable and cannot continue. People living with dementia, their families and carers have every right to be treated with respect, dignity and compassion. This of course is entirely consistent with a ‘rights based approach’, giving due prominence to the social model of disability, and promoted in the recent MHF document, “Dementia, rights and social model of disability.”

Care England’s perspective appears to be that social care and health services should be measured according to the difference they make to the lives of people with dementia. In particular it feels that commissioning should become more personalised and outcome focused through the use of increased numbers of personal budgets. The strand of policy of personalisation is a longstanding one, across all major governments in England. It was advanced in the Care Act (2014), and there has been a quietly-voiced assumption that the unified budget might become the final common pathway of health and social care integration. The political will, despite a Conservative government in 2015, is though somewhat nervousness of privatisation in places, given the considerable political backlash against the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

NHS England has led a successful programme of work across England to increase the rates of diagnosis for people with dementia as part of the Prime Minister Challenge on Dementia 2012 – 2015. This work has increased national diagnosis rates so that almost two thirds of people with dementia now have a formal diagnosis. It is now perceived that NHS England wish to turn their focus onto post-diagnostic support, but the real evidence for this currently thus far is somewhat mute.

In research, there are almost parallel universes in existence. On the one hand, there’s a goal for disease modifying drugs or symptomatic treatments by 2020. On the other hand, a systematic review of training manuals for person centred dementia care identified more than 200 available manuals, only four of which had been evaluated in clinical trials with evidence they conferred benefit to people with dementia. It is hard to tell the extent to which the transformation funds for new pharmacological therapies will elicit drugs which are inexpensive to get past NICE and to be made widely available in the NHS. It’s pretty likely that pharmacological treatments for the dementias will come in a piecemeal manner, though there’s a danger that this strand of research suffers from a bias towards Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Time will tell on whether drugs in the near future have a meaningful rôle to play in enhancing the wellbeing of people with dementia past the point of diagnosis.

It’s pretty clear that leadership for dementia services needs to be improved system wide. I feel that regional ambassadors and working groups are a great way of seeing views filtered into national practice, as Scotland has shown the way. Research and spreading of good practice in dementia care should be encouraged. This is especially an issue given there are clusters or pockets of good practice, and part of the battle is trying to spread knowledge of what good practice in care homes looks like.

It should be recognised that everyone in the UK has a universal entitlement to healthcare services, currently some people living in care homes are being charged to access services. With the integration of health and social care, no party will be able to avoid long-term the issue of funding. General taxation is by far the most equitable way of funding dementia services. Implementation of private insurance mechanisms would be particularly disastrous for dementia given increasing ability to identify genes determining dementia, and, without the protection of genetic information non-discrimination as in the US, England will need to be vigilant if it pursues avenues in genomic and personalised medicine at some later date. It will be difficult to reconcile how to bolt on a means-tested social care system onto a universal system, but the somewhat arbitrary nature of what is health and what is social care has dangers at a personal level for those diagnosed.

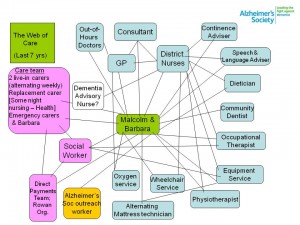

Nonetheless, it seems intuitive that health and care services should be aligned around the person, but this is an altogether simplistic view when one considers that the wellbeing of a person with dementia is intimately linked to the wellbeing of a carer and that a failure to cope from a carer can have severe consequences for the health and wellbeing of a person with dementia. Ultimately, it helps to conceptualise that care should always be person centred and integrated, in that people with dementia need to be able to move in and out of the right care settings with relative ease. Care planning is facilitated by that diagnosis of dementia, and care plans should be personalised, able to be shared and ideally electronic. Discussions about Advance Care Planning should be prominent from a very early stage, and two separate conversations should at some stage take place about when to engage palliative care services and when palliative care should commence. The problem with the term ‘end of life’ care is that it can be difficult to predict, especially for dementia, when end of life precisely occurs. When a bereavement does occur, the post-diagnostic support must have a way of helping the friends and family through this difficult time.

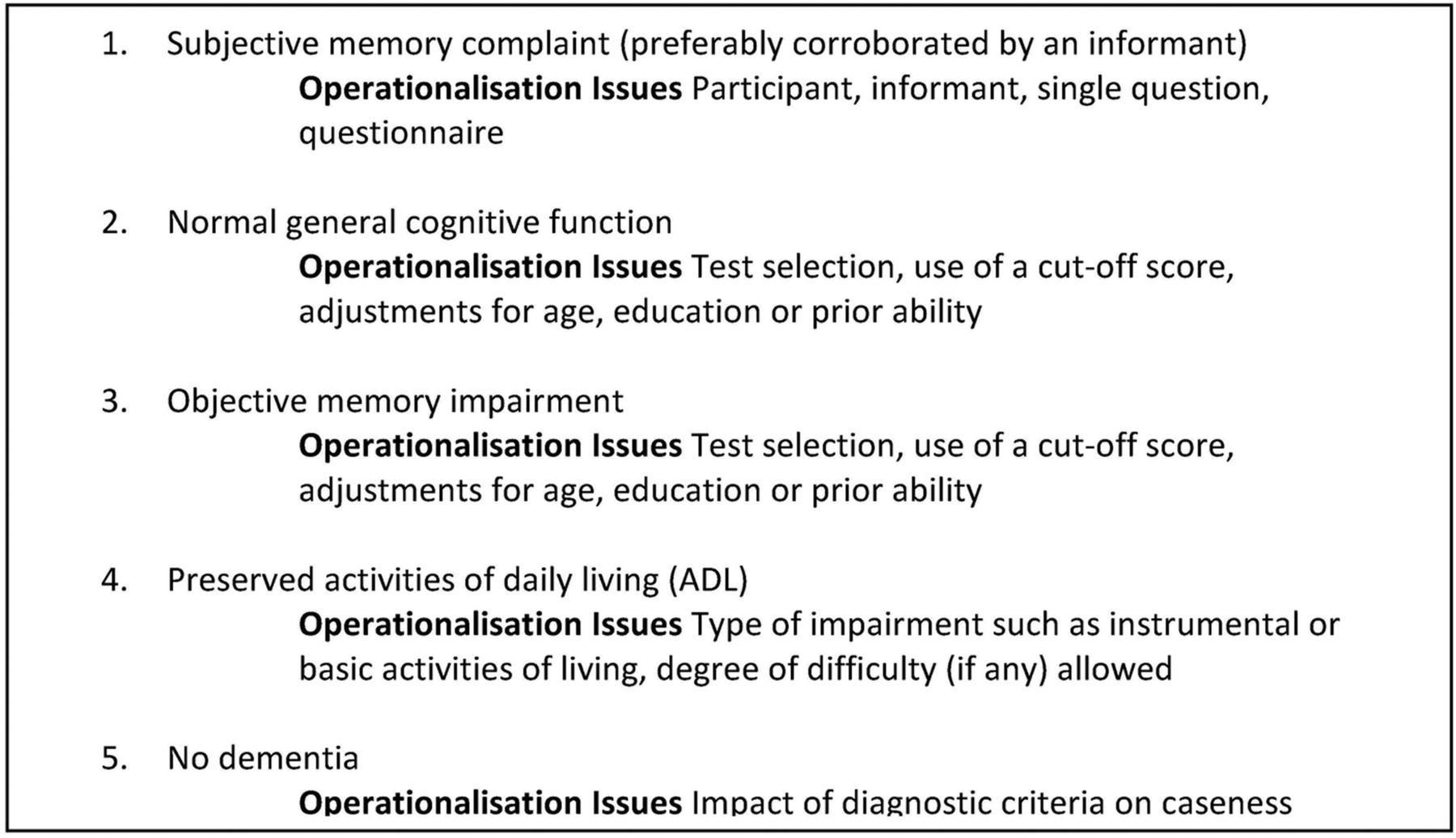

Ideally, all dementia diagnosis should be high quality and follow NICE guidelines. It is worth stating the obvious as the alternative is a huge amount of incorrect diagnoses, e.g. dementia which is in fact minimal cognitive impairment, or young onset dementia dismissed as “mid life crisis”. We therefore need some scrutiny of the way dementia diagnoses are validated across the system, and whether the workforce should include members of other specialties in addition to psychiatry or care of the elderly as ‘gatekeepers’ for the diagnosis, such as neurology, clinical psychology, general medicine or specialist nursing. There are especial difficulties with the efficacy with which the diagnosis is made, such as in people with prior learning difficulties or BAME populations. Diagnostic tools need to be redeveloped for people already in care homes who may have dementia. A diagnosis of dementia in residents of care homes, where clinically appropriate, is absolutely essential to ensure high quality post diagnosis support and care planning. All diagnosis should involve, as far as possible, the person with suspected dementia, their family and the care home staff. This is possibly the biggest caveat about the term ‘person-centred’, in that care should take in the views of friends or family (who are often unpaid carers), and shared decision making amongst all including professionals is important.

A clear narrative should be developed regarding the benefits of diagnosis – from the perspective of the person, their family, care staff and care providers. Even years after national campaigns such as ‘Dementia Friends’, it is not uncommon for the criticism to be voiced ‘but nothing can be done’. The language relating to dementia diagnosis/post diagnosis support should be made clearer and less intimidating, and there should be, I feel, systematic research into the fear of the diagnosis and subsequent symptoms of people given the diagnosis of dementia. I think there’s a legal conversation to be had at some stage after diagnosis, perhaps in the ‘life planning’ phase of post diagnostic support – this could include a discussion of wills, advocacy and power of attorney.

I think there’s a lot to be said for the notion that ‘post diagnosis support’ should be renamed to life planning (immediate) and care and support (medium to longer term) for people with dementia. There should be additional system navigation support for people diagnosed with dementia and their carers – clear outline of roles and responsibilities. I have written about whole person care in my current book ‘Living better with dementia: good practice and innovation for the future’. The trials and tribulations of Barbara Pointon and Malcolm’s care pathway are well known.

Commissioners need to better understand the vital role of the voluntary sector in supporting people with dementia for services such as dementia cafés. There should be more trained advocates for people with dementia which will in turn support system navigation. GPs need greater support to understand local support and services available for people with dementia and their carers, and need to work closely with organisations such as the Dementia Action Alliance.

Standardised personalised commissioning for people with dementia could be increased through use of personal budgets, but I have explored at great length the opportunities of ‘choice and control’ in my first book ‘Living well with dementia: the importance of the person and the environment’; and subsequently personal budgets in my second book. Budgets are of course not the only way of addressing needs; people with dementia also have legal rights afforded to them under a range of international and international instruments. Shared records and integrated IT across social care and health would be a massive advantage for the development of integrated health and social care; the current Conservative administration has promised an electronic NHS by 2018, but one waits to see whether this promise will hold up.

Care home staff should have equal access to training and development opportunities as health care staff. I think there have been great strides in education of the workforce, including the new skills, education and training framework and Care Certificate from Skills for Care. I do worry about care homes being perceived as ‘outside of’ the community, and this might explain to some extent why a minority of care homes really do provide really bad care. Dementia friendly communities could have an increasingly important role to play. Care homes should become key parts of the community.

There needs to be greater definition of what makes ‘dementia friendly communities’ inclusive or accessible. Additional housing for people with dementia should be planned – better adaptation means more dementia friendly. And the same holds for transport. People with dementia should be paid consultants in the design of such services; I agree in co-production, but I do not condone exploitation. Valuing people with dementia and carers through paid work which is service-related, I do believe, is now a must for all levels of engagement and empowerment.

Greater investment should take place in services that prevent hospital admission and enhance discharge. People with dementia are very often living with other co-morbidities, and anticipating illness and disease must be fundamental to organising health and social care services. Adult social care has a pivotal rôle to play in upholding key principles of social justice, fairness and equality; as well as promoting wellbeing in the best traditions of Tom Kitwood. Perhaps health and wellbeing boards should be incentivised to integrate social care and health commissioning for people with dementia, or NHS England could ultimately detach itself from the activity-based tariff system which potentially promotes illness and fixing it towards a whole person-tariff to promote wellbeing.

Finally, I feel there are obvious gaps in England’s policy and strategy for dementia. “Achieving world class cancer outcomes: a strategy for England for 2015-20” from the Independent Task Force/Cancer Research UK was a massive advance earlier this year. I have no wish to dismiss the important role of dementia advisers and dementia support workers, but the harsh truth we are increasingly expecting people to signpost to rapidly disappearing services (in the name of austerity). Even specialists in cancer feel that they have progressed as far as they would have liked, but there personalised care plans and clinical specialist nurses are more accepted in the framework of national policy and debate. I think, as long as we do not plug this gap in system provision, and the benefits of clinical nursing specialists are well rehearsed elsewhere, England will not be in a position to produce a credible care pathway for dementia. Beyond the loud rhetoric, this would be a massive tragedy for people with dementia and carers.