Diagnosing any clinical condition is arbitrary, as it depends upon a person meeting certain criteria.

Diagnosing any clinical condition is arbitrary, as it depends upon a person meeting certain criteria.

For brain disorders, the extent to which people meet certain criteria or not might mean they satisfy the diagnosis of ‘dementia’. The word ‘dementia’ has a public perception of its own, that’s why clinicians are very aware that when this diagnosis is disclosed it’s effectively being disclosed to a person’s friends and/or family as well.

I myself am physically disabled, and yet I am able to live well with my physical disability. I see double ‘all of the time’, due to the meningitis I lived through in 2007. I am able to pay taxes, and do my shopping, on my own. As such, I am ‘functionally independent’.

If I have a memory problem, or mild problems in cognition, but which are not so bad, and certainly not bad enough to impinge on my everyday life, I might be classified as having a ‘mild cognitive impairment’.

To put it succintly, “mild cognitive impairment” is a clinical diagnosis in which deficits in cognitive function are evident but not of sufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia (Nelson and O’Connor, 2008).

That’s why putting the diagnosis in primary care down to a simple question ‘do you have problems with your memory?’ can often lead to a doctor seeking confirmation bias for making the diagnosis of dementia, when the diagnosis might not be dementia at all. In an older person, it might be the mild amnestic syndrome, or even depression.

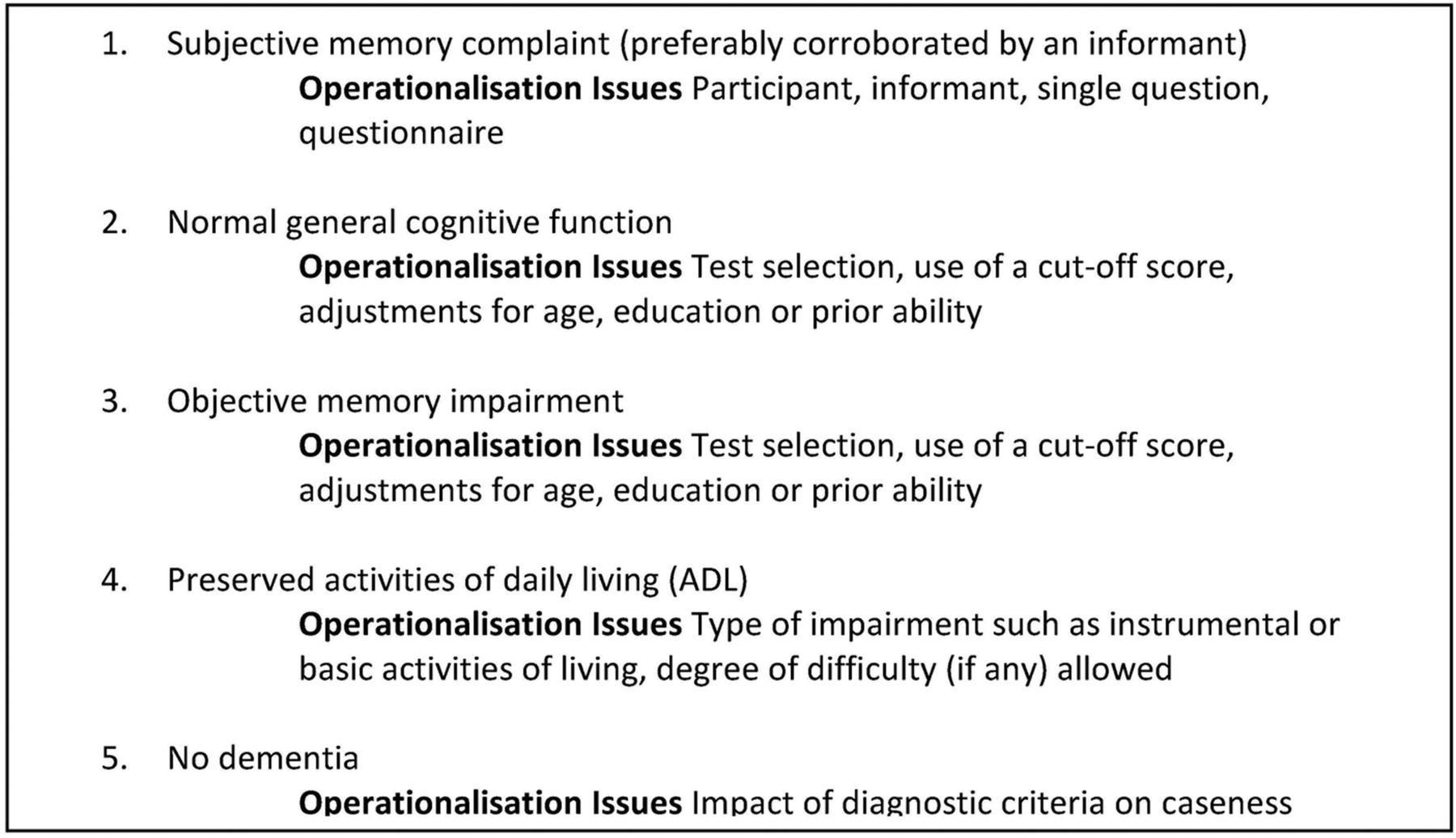

In fact, looking at the trials as indeed Christa Maree Stephan and colleagues did in 2013, there’s a lot of scope of fuzziness in whether or not a person might receive a diagnosis of ‘amnestic mild cognitive impairment’ (“aMCI”).

This is a figure reproduced from their paper (under the ‘Creative Commons’ licence).

When, a few years back, some clinicians revised the criteria for the aMCI, they were aware that many people with dementia would become re-classified as having aMCI.

As I have stated many times before, however, the evidence of progression of MCI (mild cognitive impairment) to DAT is currently weak. It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009).

When NHS England decided to launch a policy of incentivising dementia diagnoses, most clinicians knew this was playing with fire, as it was setting people up to receive incorrect diagnoses of ‘dementia’. My colleague Dr Martin Brunet once elegantly referred to ‘the cobra effect‘, in a workshop I attended at the King’s Fund on their leadership in dementia day.

Ken Clasper recently brought up the subject in a blogpost called ‘Rediagnosis from one dementia to MCI’ on his popular blog ‘Living well with Lewy Body Dementia’. Ken in this blogpost successfully touches upon the disorientating effect that this re-diagnosis can have.

I watched reaction to this blogpost on the social media, and many of the opinions were in the philosophy of clinicians ‘not doing their job’ properly. In fact, I have seen this approach taken regularly in recent years in videos instigated by caregivers with a subtext of ‘time to teach the medics’. And I certainly don’t deny that there is plenty of scope for teaching the medics on many things.

But one would think that, if a diagnosis needs to be changed, then it is better that the medic swallows professional pride and is open with the new diagnosis. There are valid reasons why the diagnosis might be changed, if only the diagnostic criteria have changed, or the symptoms of a person thought originally to have dementia are different to those expected.

And should medics be blamed for having incorrect diagnostic tools? Possibly. But I remember when I was a junior the eminent neuroradiologist at the time at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery emphasising that you can never make a diagnosis of dementia on CT alone. There are people who have shrunken brains due to ‘normal ageing’. And likewise, I’ve seen many people who later develop clear-cut dementia who’ve had normal brain scans to begin with (particularly for some certain types of dementia, such as the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia).

But of course neither can clinicians be blasé about the diagnosis of dementia. One would have thought that England, which wishes to close the ‘dementia gap’ (i.e. finding the numbers of people who have dementia who remain undiagnosed with dementia), should wish to put resources into people who can make the diagnosis.

You’ll see from the table above it’s not that reliable to say for certain whether somebody’s developing a dementia from a ten minute chat in a busy GP surgery. You’d be fooled into thinking from the popular media that most GPs either do not want to make the diagnosis of dementia, or are incapable of doing so. This is of course a massive professional slur on GPs, but sadly had become an increasing trend as vindictive criticism of medics, as well as criticism of medics, has become a popular past-time.

The aphorism goes ‘the diagnosis of dementia is not meant to be a label, and it certainly is not meant to be disabling but enabling’. People’s lives are changed with a diagnosis of dementia inevitably, especially since the media have been far more successful in promoting the programme ‘Dementia Friends’ than in promoting the need for service provision from trained clinical specialist nurses or promoting the idea that it is possible to live better with dementia.

The mood music has changed. We’ve got another thrust of policy where we are all drug trial guinea pigs now. And many people have vested interests in promoting the idea that there is a pre-symptomatic phase of dementia, called “pre-dementia”, which is amenable to treatment. This of course is part of the whole problem of the over-diagnosis trend which Dr Iona Heath has brilliantly discussed. Similarly, I feel Prof John Yudkin has been right to draw attention to the similar phenomenon of ‘pre-diabetes‘, which many of us feel serves the function of opening up new markets, patients who can become customers for drugs. Deborah Orr’s article on over-medicalisation of illness in general is brilliant, and I strongly commend it to you.

In a nutshell, it’s time we spoke about ‘mild cognitive impairment’ in relation to dementia? A certain bandwagon in dementia policy has gone ‘too far too fast’. This was a favourite catchphrase of Ed Balls – and look what happened to him.

Reference

Christa Maree Stephan B, Minett T, Pagett E, Siervo M, Brayne C, McKeith IG. Diagnosing Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in clinical trials: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013 Feb 4;3(2). pii: e001909. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001909. Print 2013.