Certain General Practitioners are ‘on heat’ as they take great delight in identifying that dementia does not meet current screening criteria, but they are missing their targets of creating maximum fuss but totally missing the point. In their narrow world, they define “benefit” as a treatment such as a magic bullet. “Benefit”, I believe even under the Wilson and Jungner (1968) construct, can mean something much wider, and ultimately the authors give a very big sense of this being for the benefit of the person or patient not the benefit of the physician. We simply have a lack of evidence base for living well with dementia, due to charities which focus on cure, care and prevention. Without this evidence, we cannot say, any of us, however big or small in the medical establishment or outside, that there’s “no benefit”. Carts and horses spring to mind. This is a good case of medical hierarchy being utterly irrelevant to ‘who is right’, and more importantly ‘what is right’ for the person trying to live well with dementia after his or her diagnosis.

There’s no doubt about it. There’s been an intense policy drive to encourage people with memory problems ‘to present themselves’ for early diagnosis, and various devices have been used to encourage this, including participating in drug research (hence the extreme media publicity for a ‘drive for a cure’). Screening for dementia is a pot of gold for the ‘dementia health economy’, even more so than “Dementia Friends”, as it produces a new market for people who might be eligible for a drug treatment that ‘stops dementia in its tracks’ one day. But some of the confusion has come from the extent to which the screening criteria embraces early symptomatic persons as well as completely asymptomatic ones, and official guidelines, derived from Wilson and Jungner (1968), are not solely for early symptomatic people. But the irony is that the relentless focus on the medical model, without resources going into demonstrating the efficacy of wellbeing interventions as a way of ameliorating morbidity in dementias, including Alzheimer’s Disease, may be ultimately stopping the screening criteria being met, denying access of Big Pharma to this pot of gold. But the way in which Big Pharma has a stranglehold on big charities and research programmes, epitomised by the recent G8 dementia summit in Lancaster House frontloading personalised medicine, could be entirely to blame.

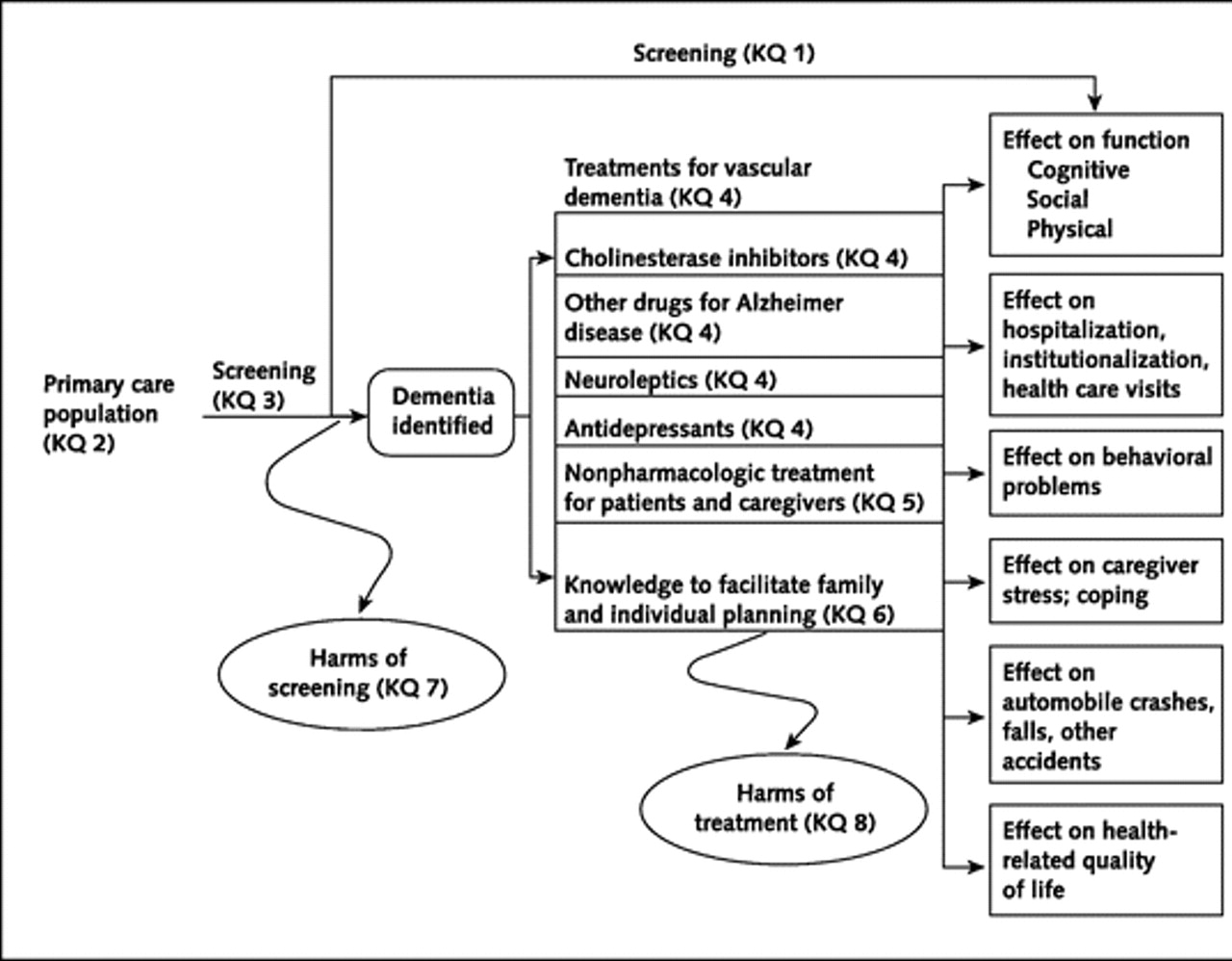

Various intellectual frameworks have, for example, been proposed for the screening of dementia in primary care outside of this jurisdiction. For example, this scheme appeared in the following paper.

The UK NSC policy on Alzheimer’s Disease screening in adults is in fact clear. A systematic population screening programme is not recommended. The National Screening Committee criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme are based on the criteria developed by Wilson and Jungner in 1968 and address the condition, the test, the treatment and the screening programme. The need to refine them in the genomic age is illustrated in this statement from WHO in 2008. I have no intention of discussing the usual issues of screening/early detection, such as the distress caused by a false diagnosis, described elegantly elsewhere.

There is no doubt that the drives for screening at all under standard criteria suffer from a lack of inexpensive test which is sufficiently sensitive and specific – but this might be a temporary situation, and might be ultimately resolved one day with the correct ‘mix’ of questions, say in testing a wide range of neurocognitive functions. What is clearly untenable is sticking a large needle into the backs of all people who might be at risk of developing dementia to collect cerebrospinal fluid for biomarkers, or doing expensive MRI scans on everyone (notwithstanding the known limitations of brain scans in making the dementia diagnosis.)

A significant stumbling block is that there should be evidence from high quality Randomised Controlled Trials that the screening programme is effective in reducing mortality or morbidity. Clearly, drugs in reducing mortality for Alzheimer’s disease, which is only one type of dementia, have been lacking. The conclusion that there have been no randomised controlled trials to show that a screening programme for Alzheimer’s disease would be effective in reducing mortality or morbidity. But in fairness there has NEVER been a drive to collect a robust body of information on the long term effects on living well with dementia from an early diagnosis of dementia. Nobody has wished to fund it. The data are lacking. Decades and millions at least have been chucked into the aim that the drugs which ‘don’t work’ (and in fact can have dreadful side effects).

It is interesting that the stumbling block is not the lack of pre-symptomatic stage, though interestingly the National Screening Committee never make reference to mild cognitive impairment, which people who do not understand the evidence incorrectly refer to as ‘pre-dementia’. It is argued, for example, that during the pre-symptomatic period there is a gradual loss of axons and neurons in the brain and at a certain threshold the first symptoms, typically impaired memory for events and facts appear.

And it’s a useful context to think about the ethos in which the Wilson and Jungner criteria should be applied? Wilson and Junger themselves used the term ‘principles’ for ‘ease of description rather than from dogma’. It is unlikely that any screening programme will be able to fulfil all of these criteria to everyone’s satisfaction in any case. The question therefore arises as to whether each criterion has equal merit, or whether there is a hierarchy of importance using this construct. Wilson and Junger felt that ‘of all the criteria that a screening test should fulfil, the ability to treat the condition adequately, when discovered, is perhaps the most important’.

And the build up of these criteria emphasise the clinical method, although the literature in reviewing data results as a desktop exercise is massive. Jungner and Wilson themselves state:

“The medical history is very important, and can be obtained by appro- priate questionaries. It has been reported from many investigations that the medical history and the physician’s physical examination make the greatest contribution to the diagnosis. However, most of the diagnoses are then known before the screening procedures. How much medical value is afforded by the notation of earlier known disease remains to be seen. Obviously, the information is most useful the first time an examination is undertaken. The history is of immense value and the advantage of questionaries is great.”

Jungner and Wilson refer to their review of relevant papers in the 1950s, and their criticisms of case-finding in the absence of seeing the big picture are well known from close reading of their paper.

They cite:

“Some of the chief points made in these papers were:

(1) Case-finding by multiple screening is a technique well suited to public health departments, whose role is changing.

(2) Provision for diagnosis, follow-up and treatment is vitally impor- tant; without it case-finding must inevitably fall into disrepute.

(3) Tests must be validated before they are applied to case-finding; harm may result to public health agencies’ relationships with the public (not to mention the direct harm to the public), and with the medical profession, from large numbers of fruitless referrals for diagnosis.”

Putting all your eggs in the investigations basket has been a discredited approach in the past in neurology. 71 investigators who conduct MRI studies in the United States and abroad took part in a particular study and 82% percent (54/66) reported discovering incidental findings in their studies, such as arteriovenous malformations, brain tumours, and developmental abnormalities. Auhors of that particular paper (J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2004;20:743–747) proposed that guidelines for minimum and optimum standards for detecting and communicating incidental findings on brain MRI research are needed.

So is it viable to do backdoor collection of data to identify cases? Wilson and Jungner indeed describe this failed approach in diabetes detection, according to Joslin and colleagues this work goes back to 1909, when Barringer had reported the findings on over 70 000 persons examined for life insurance purposes. Wilson and Jungner themselves noted that, “Despite all this work it is still difficult to evaluate the results in terms of benefit to the populations screened. Some of the criteria for case-finding discussed above remain unsatisfied.”

So this lack of intelligent thinking from the medical profession has come full circle many years after the original Wilson and Jungner paper. General Practitioners increasingly now recognise the importance and benefits of a timely and explicitly disclosed dementia diagnosis. But it’s argued that there are many barriers to diagnosis at both the physician and patient level. Barriers at the physician level include time constraints, insufficient knowledge and skills to diagnose dementia, therapeutic nihilism and fear to harm the patient.

But it’s impossible to skirt around the basic ‘rules’ of medical ethics, much as non-clinicians in the dementia economy might like to. These include respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficience and justice. And doing things without a patient’s consent, if they have mental capacity, is ethically offensive and legally could constitute assault or battery. This issue has been seen in coeliac disease previously, reported in a paper about a decade ago (Gut. Jul 2003; 52(7): 1070–1071):

“Although the investigational process for population screening and case finding may be the same, there is an important ethical difference between them. If a patient seeks medical help then the physician is attempting to diagnose the underlying condition (for example: patients with CD who present with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome). This would be classified as case finding and clearly it is the patient who has initiated the consultation and in some sense is consenting for investigation. Conversely, individuals (who are not patients) found to have CD through screening programmes, may have considered themselves as “well” and it is the physician or healthcare system that is identifying them as potentially ill.”

And these ethical concerns appeared originally in the mid 1980s with HIV testing. HIV is used as the “poster boy” in the drive for a cure for dementia, but it’s worth remembering the history of this situation too. Prior to an effective treatment, ethical concerns centred on the right of patients not to be tested, since an HIV diagnosis provided few medical benefits and posed serious risks of stigma and discrimination. The 3Cs were identified of “counselling, voluntary informed consent and confidentially”. But with the availability of ART drugs, there was accumulating evidence that ART can prevent transmission of HIV, strengthened public health arguments for scaling up testing. This led to a reformulation of guidelines, such as “Testing the gateway to prevention, treatment and care” when in 2007 WHO recommended PITC (provider‐initiated counselling and testing)

Nevertheless, the primary care setting in England provides unique opportunities for timely diagnosis of dementia. It has just been reported that GPs will be given more leeway to use their clinical judgement in deciding when to offer dementia assessments under a revamp of the specifications for the controversial dementia case finding DES. Under the agreed changes, GPs will still be required to offer the assessments to the same ‘at-risk’ groups of patients on their list, but only if the GP feels it is ‘clinically appropriate’ and ‘clinical evidence supports it’. At-risk groups again include patients aged 60 and over with vascular disease or diabetes, those over 40 with Down’s syndrome, other patients over 50 with learning disabilities and patients with neurodegenerative disease.

And, this is broadly consistent with approaches from other jurisdictions. Case finding remains the preferred approach to identifying patients with dementia and Alzheimer disease, according Australian experts, after a US advisory body found insufficient evidence to support universal screening for cognitive impairment in older patients.

Professor Dimity Pond, professor of general practice at the University of Newcastle, agreed that there was insufficient evidence for screening. Professor Pond said further a false-positive diagnosis could also cause a lot of distress to the patient and their family. “It’s a huge diagnosis to be made — it causes their family to worry about the need to start activating power of attorney, selling the house and putting them in a nursing home.”

Wilson and Junger themselves do not, however, specify whether patients, a third party, or society as a whole, should prioritise importance, and the utilitarian part of this economics discussion is lacking in temporal and geographical jurisdiction (in the same way that G8 hopes to meet its objectives likewise). J.S. Mill, in his celebrated essay “On Liberty”, argues that ‘there is no one so fit to conduct business, or to determine how or by whom it shall be conducted, as those who are personally interested in it’. But it is in reality difficult for an individual patient to be objective as to whether his/her health problem is more important than that of another patient or whether he/she deserves scarce resources in preference to others: it is impossible for an individual patient to make that comparison because of patient confidentiality, for example.

And policy makers need to be able to justify why memory problems are sufficient to trigger a particular care pathway, when a cough does not necessarily trigger full investigations for emphysema, or a headache does not trigger necessarily a full work-up for a brain tumour. The general rule for a ‘care pathway’ is “treating the right patient right at the right time and in the right way.”

I feel a fixation on ‘benefit’ as defined through the prism of the Pharma part of the health economy has led to a wilful neglect for wanting to find any beneficial outcomes in wellbeing from a timely diagnosis, such as improved design of the home, design of the built environments, and access to advocacy. But ultimately, regardless of the health economy and the lack of proper scrutiny of the issue, it is persons with dementia and their caregivers who I feel are suffering most, at the hands of the large charities and Big Pharma. GPs and medics are simply unable to say there’s “no benefit” for finding cases of dementia, whether it is screening or not, if the evidence base on living well with dementia is simply absent. Try to put the horse before the cart next time.