The first (and thus far) only English dementia strategy was published by the Department of Health in February 2009. Entitled “Living well with dementia” it was described accurately that under-diagnosis of dementia was the norm.

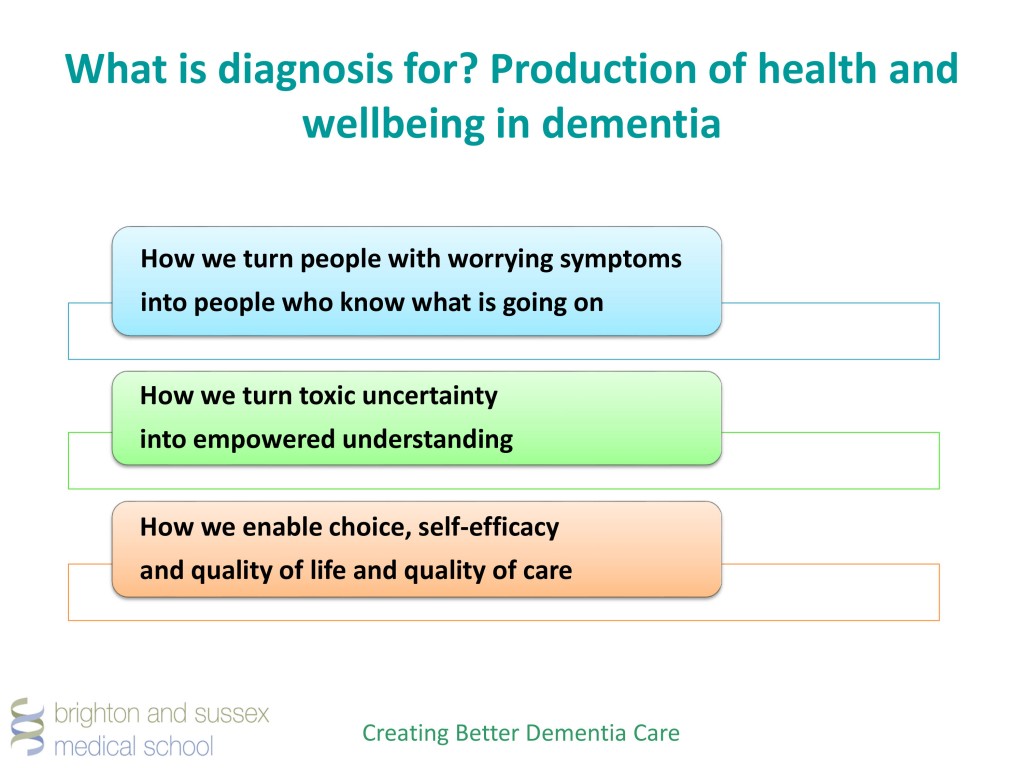

The current feeling about this diagnosis is that it should be a ‘timely diagnosis’. In other words, it should be delivered in a person-centred way, at a time that is right for the person receiving the diagnosis.

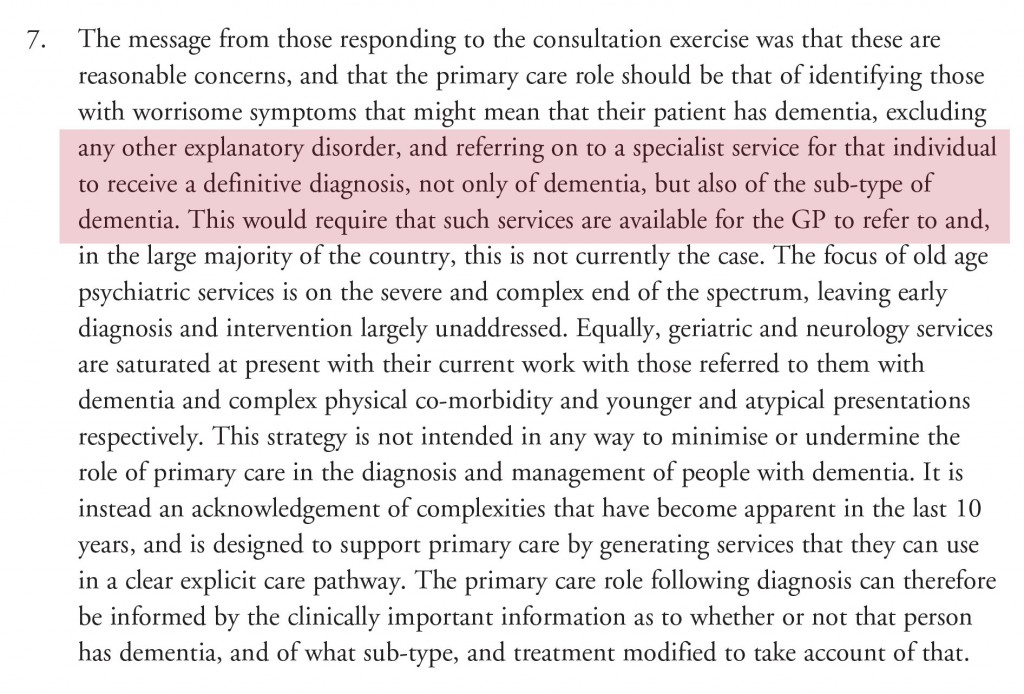

The critical recommendation is that a specialist diagnosis should be provided at some stage.

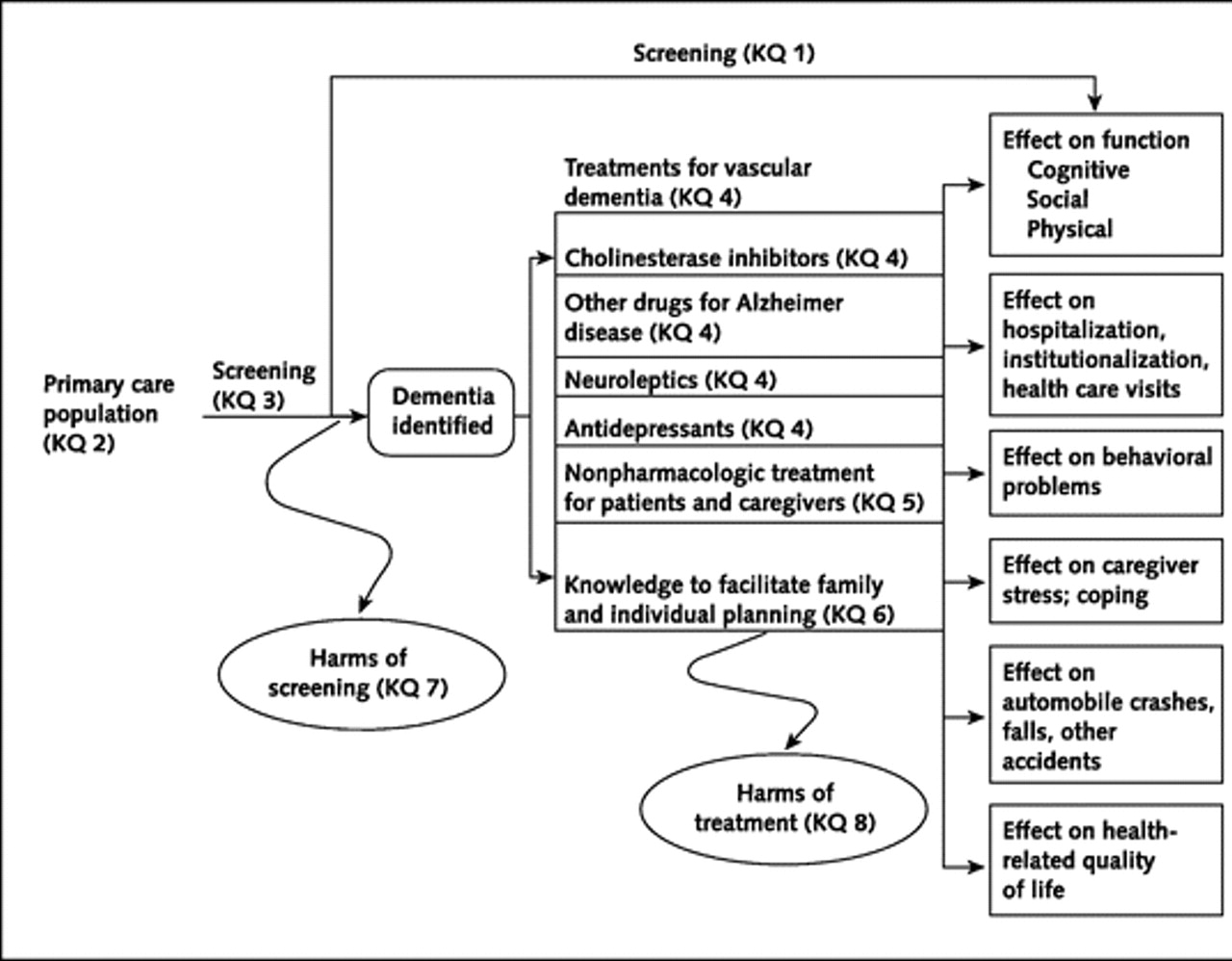

The type of dementia is indeed relevant. For example, it is possible to target cardiovascular risk factors, such as bad cholesterol, smoking and high blood pressure, to slow down the progression of vascular dementia. Also, say, in diffuse lewy Body dementia a doctor would be wise to avoid prescribing certain medications.

In Chapter 4 of the Department of Health’s “Living well with dementia” (2009), the issues presented by a badly timed diagnosis are provided.

Currently only about one-third of people with dementia receive a formal diagnosis at any time in their illness. When diagnoses are made, it is often too late for those suffering from the illness to make choices. Further, diagnoses are often made at a time of crisis; a crisis that could potentially have been avoided if diagnosis had been made earlier.

Looking at the reality, it is impossible for GPs who are clearly overstretched (as today’s #LMCConf bears out) to be able to make a definitive diagnosis of dementia in a ten minute consultation (or even a twenty minute consultation if a “double slot”).

The question “do you have problems with your memory?” is clearly a daft screening test as, whatever its sensitivity, its specificity is poor. It will pick up problems in memory ranging from the ‘worried well’ to severe depression.

Secondly, a major problem is in the diagnosis of young onset dementia, defined arbitrarily as dementia before the age of 65. One possible cause of this is posterior cortical atrophy, possibly a variant of Alzheimer’s disease, where the predominant initial symptom is in higher order visual processing. Invariably, memory is OK. Memory also tends to be relatively OK in the frontal form of frontotemporal dementia.

The need for referral to specialist services is a very important one. Hospital doctors have a considerable advantage in being able to make the precise diagnosis of type of dementia, with access to sophisticated neuroimaging, blood tests, detailed cognitive psychometry, brainwave scans (EEG) and also tapping off cerebrospinal fluid through lumbar puncture.

The precise gamut of investigations, in addition to a detailed history and examination of the possible proband of person with dementia (and a history, equally of about an hour, from a reliable witness such as a family member), will depend on how obvious the diagnosis is, perhaps.

Some, in very unusual cases, may even require a biopsy of skin, nerve, muscle or brain.

The need to close the ‘diagnosis gap’ was a laudable good intention of the All Party Parliamentary Group 2012 report entitled “Unlocking diagnosis”.

Prof. Sube Banerjee was one of the co-authors of that important document. At a fringe meeting of a day at the King’s Fund, “Leading change in dementia diagnosis and support” in February 2015, on which I was included as a member of the main panel discussion, Banerjee returned to the importance of the correct diagnosis of dementia.

The UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) in January 2015 upheld its recommendation against screening everyone aged 65 and over for dementia.

This is clearly the correct decision to me.

There is no screening test which is sensitive and specific enough to pick up the dementias. Bear in mind there are over a hundred different types of dementia (depending on how you count them).

Dr Anne Mackie, Director of Programmes for the UK NSC, said at the time:

While the current test would identify people with mild cognitive impairment, many of them would not go on to actually develop dementia. The evidence shows us that for every 100 people aged 65 tested, 18 would test positive, but only 6 of these would have dementia and 1 case would be missed.

This means we cannot recommend universal screening.

The whole situation was further complicated with NHS England’s ubiquitously criticised decision to incentivise general practitioners through QOF to make a diagnosis of dementia, leading to some pretty untastely headlines – including even in the Financial Times.

This undermined potentially trust in the doctor-patient relationship, where it was known that there was now financial pressure from Government to make the diagnosis. Some in Big Charity even intimated that it was the general practitioners’ fault for not making the diagnosis, when the medical profession through their training were well aware that there exist complicated issues for why patients seek a diagnosis of dementia (for example as described here by Werner and colleagues in 2014).

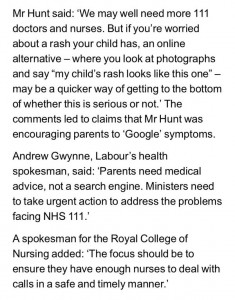

So actually what happened was ‘demand management’ in the wrong direction. Jeremy Hunt raised expectations through a media war on late diagnosis of dementia (as below), when all along the critical issue is how long people have to wait to get a correct diagnosis of dementia from a specialist, such as memory clinic.

The fundamental issue is that a diagnosis delayed is a diagnosis denied. People languishing in waiting for a specialist referral, to find out whether they have dementia or not, having been told that they might have dementia, is quite sadistic, some might say. Certainly not an approach endorsed by the medical profession.

This is not of course the first and only time Jeremy Hunt has actively done harm from a public health perspective. His other interventions on stroke and skin lesions (from tweet) have been equally potentially disastrous, worthy of a clinician being under a spotlight, some might argue, by his or her regulator.

But what is happening after this delay while people are waiting for the diagnosis from specialist services?

Some people find out that they don’t have dementia at all. For example, Ken Clasper has blogged openly about how he became re-diagnosed with minimal cognitive impairment, with considerable personal readjustment.

To put it succintly, “mild cognitive impairment” is a clinical diagnosis in which deficits in cognitive function are evident but not of sufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia (Nelson and O’Connor, 2008).

However, the evidence of progression of MCI (mild cognitive impairment) to DAT is currently weak. It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009).

It is not necessarily the case that a clinician makes the ‘wrong diagnosis’. But this a big deal – as a wrong diagnosis of dementia subjects someone to a pretty life changing event in itself, and also there’ the opportunity cost of not having the actual condition being managed properly?

Firstly, I explained previously how GPs can only make a working diagnosis in severe scare resource restraint in time and funding. There is too much of a rampant blame GPs culture currently.

Secondly, clinical presentations change can all the time. By the time a patient gets to see a professional in a specialist service, his presentation might be more florid or obvious. The symptoms could be more obvious, for example.

Thirdly, specialist services have access to tests which can refine the diagnosis. For example, it is not uncommon for a diagnosis of vascular dementia to be added to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, if a patient presents with a particular type of brain scan – this information would not necessarily have been known to the general practitioner.

Fourthly, I don’t believe that you can suddenly wake up with dementia one morning and not have dementia the previous day. The development of a dementia is a gradual process; all that changes is whether a particular individual fits within a particular diagnostic criteria.

And these criteria change all the time.

When, a few years back, some clinicians revised the criteria for the aMCI, they were aware that many people with dementia would become re-classified as having aMCI. This ‘reclassification’ of diagnosis might have substantial effects, for example, on a State funding benefits.

In an ideal world, you’d want to follow serially for a while a person with possible dementia to see if that person’s cognition or behaviour is indeed markedly changing. This would be an ideal built-in requirement for the diagnosis of dementia as the most common dementias are by definition chronic irreversible and progressive, caused by conditions of the brain.

The delay while someone is waiting for specialist services serves another function too.

Remember the Government statement about the national screening committee? It also contained the following.

Dr Charles Alessi, dementia lead for PHE, said:

In the absence of a treatment or cure, it is important that we take action to reduce the numbers of people getting dementia, delay the onset of dementia or reduce its impact.

PHE and the UK Health Forum published the ground-breaking Blackfriars Consensus earlier this year, which makes the case for concerted action to reduce people’s risk of dementia by supporting them to live healthier lives by doing things like eating well, being active and not smoking.

The mood music has changed.

Firstly, we’ve got another thrust of policy where we are all drug trial guinea pigs now. And many people have vested interests in promoting the idea that there is a pre-symptomatic phase of dementia, called “pre-dementia”, which is amenable to treatment. This of course is part of the whole problem of the over-diagnosis trend which Dr Iona Heath has brilliantly discussed.

Similarly, I feel Prof John Yudkin has been right to draw attention to the similar phenomenon of ‘pre-diabetes‘, which many of us feel serves the function of opening up new markets, patients who can become customers for drugs. Deborah Orr’s article on over-medicalisation of illness in general is brilliant, and I strongly commend it to you.

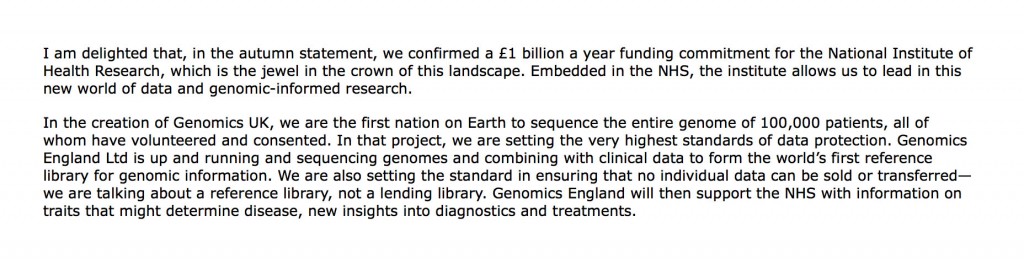

Your risk of developing dementia might be made possible with your personal genomic scan being done in the future. And with the results, you might possibly be tempted to seek private health insurance. Risk is fundamental to how that industry works.

It is well known the warmth with which the current Government discusses informatics/Big Data and personal genomics.

Take for example George Freeman MP talking in parliament on 29 January 2016. This is the sort of stuff which public-private collaborations are made of, where the State can underwrite future shareholder dividends in private companies, and where the NHS can finally export an aspect of dementia care as ‘profitable’.

The Hansard entry goes thus:

Public health, despite formidable cuts from the current Government in their spending review, remains big business. This was elegantly discussed in an article in the British Medical Journal on the ‘corporate capture of public health’ in 2012. [Mindell, JS; Reynolds, L; Cohen, DL; McKee, M (2012) All in this together: the corporate capture of public health. BMJ (Clinical research ed), 345. ISSN 0959-8138.]

Secondly, people who are told they ‘maybe have dementia’ can enrol onto research programmes. There is now a national aspiration for the number of people to be enrolled through programmes such as #JoinDementiaResearch. Or people may simply be encouraged to donate directly to charity to fund dementia research, with an agenda skewed in a direction away from quality of care towards ‘future treatments’.

But I do feel, as leading campaigner Dr Martin Brunet clearly does, that we should continually be on guard as to who exactly benefits from the current dementia policy.

An apt starting point will be to know for certain what are the regional variations in the wait to get to memory clinics from primary care. We also need to know roughly want proportion of diagnoses at primary care need to be revised.

And finally, we need to know what to do about this (for example is there a case of further training of health professionals in the diagnosis of dementia?)

What we don’t want is an expedited diagnosis which turns out to be wrong. The leading campaigner Chris Roberts, living with mixed vascular and Alzheimer’s dementia, has specifically warned about this in public conferences.

A quote often misattributed to Joseph Stalin is, “The … of one man is a tragedy, the … of millions is a statistic.” I do not want this debate to blame anyone (especially when the medical profession is doing its utmost for this policy). I want us to learn constructively from where things have clearly gone wrong. This will be for the benefit of all NHS patients.