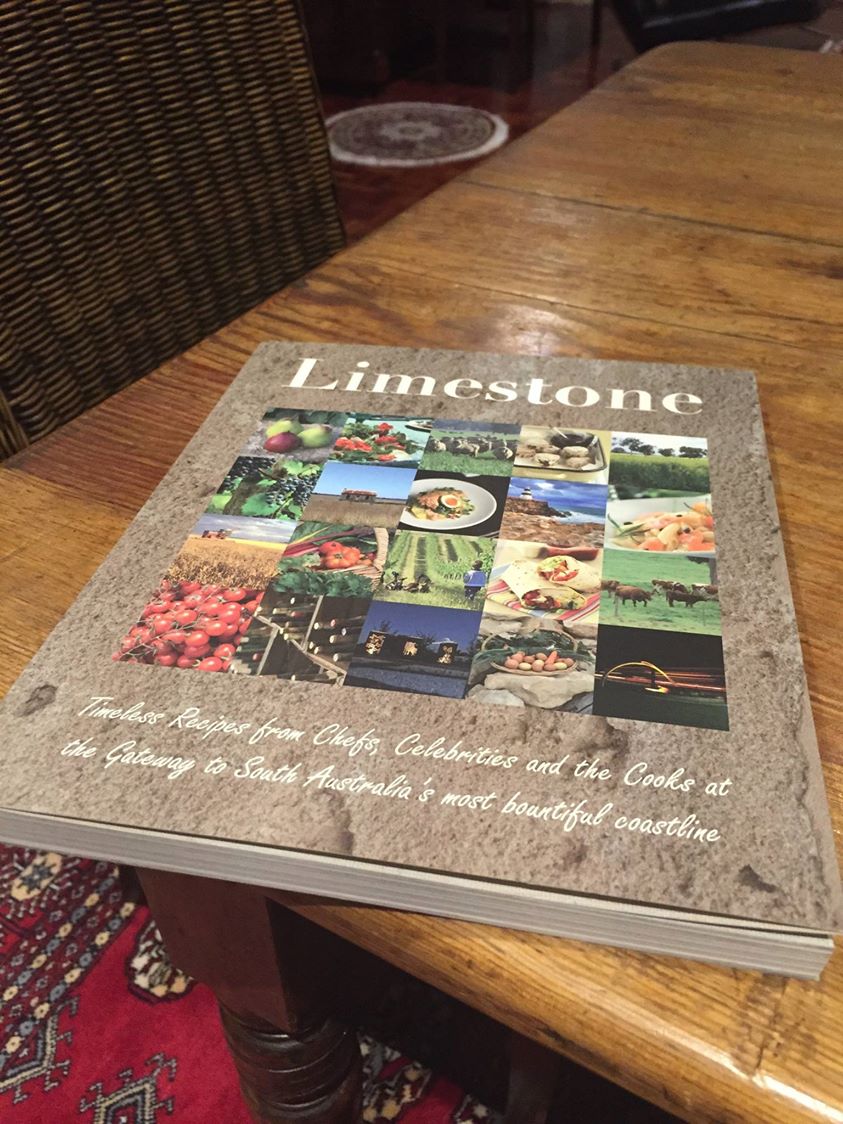

For some time, Kate Swaffer had been suggesting to me that I should watch one of her favourite films ‘Babette’s Feast’.

In case you were unaware, one of Kate’s remarkable talents is high-end cuisine. Kate even ran a restaurant. I went past it in a mini van while I visited Adelaide suburbs earlier this year.

In case you haven’t yet seen this extraordinary, remarkable film, I do not wish to do any spoilers. I do need to tell you some basic details though – it involves Babette producing a meal for twelve people, consisting of top quality courses. She barely has any help, but does it all to budget. There is no money left at the end of the evening.

If you are desperate to know the plot of the film, please refer to the synopsis here.

Health and social care often look to other sectors to look for best practice. For example, only this afternoon, Jeremy Hunt made reference to two hundred ‘avoidable deaths’ in the NHS every week; ‘the equivalent of an aeroplane’. Travelling by air, for example the use of checklists, has become a paradigm for patient safety.

I started watching ‘Babette’s Feast’ just after midnight this morning. It finished before 2 am. It is an amazing film. You’ll see why when you watch it.

But in passing I could not of course help but think about the parallels between preparing a complicated meal for guests with ‘dementia care’. I’ve always had problems with the term ‘dementia care’ as it can sound very robotic. I think it is a rather unemotional term for something at the heart of humanity – that is looking after someone.

Is it that ‘dementia care’ sounds transactional? I think this issue of carer versus care recipient is problematic if there is a problematic power imbalance.

Back to the dinner party.

It is no small achievement for Babette to provide a meal with a number of courses, such that all the dishes arrive on time. This is a big operational ask.

But it is highly significant that the dishes had personal resonance for the guests – often invoking memories. Such evocation of memories, further, could lead to a massive outpour of wellbeing.

The meals together can cause the guests to feel much more content, such that they enjoy each other’s companies – overall the group’s wellbeing is much enhanced.

Therefore, Babette’s feast is more than a set of dishes. It has personal resonance for the people involved – making it unique.

Babette neither profits or makes a loss on the meal (for reasons I don’t want to go into, otherwise it gives a key detail of the plot away.) The ‘outcome’ is that all the guests end up very happy.

In this current climate, it is all very easy to become enveloped in the ‘costs of caring’ and operationalising care. But this is of course to take away something very special which you can’t bottle.

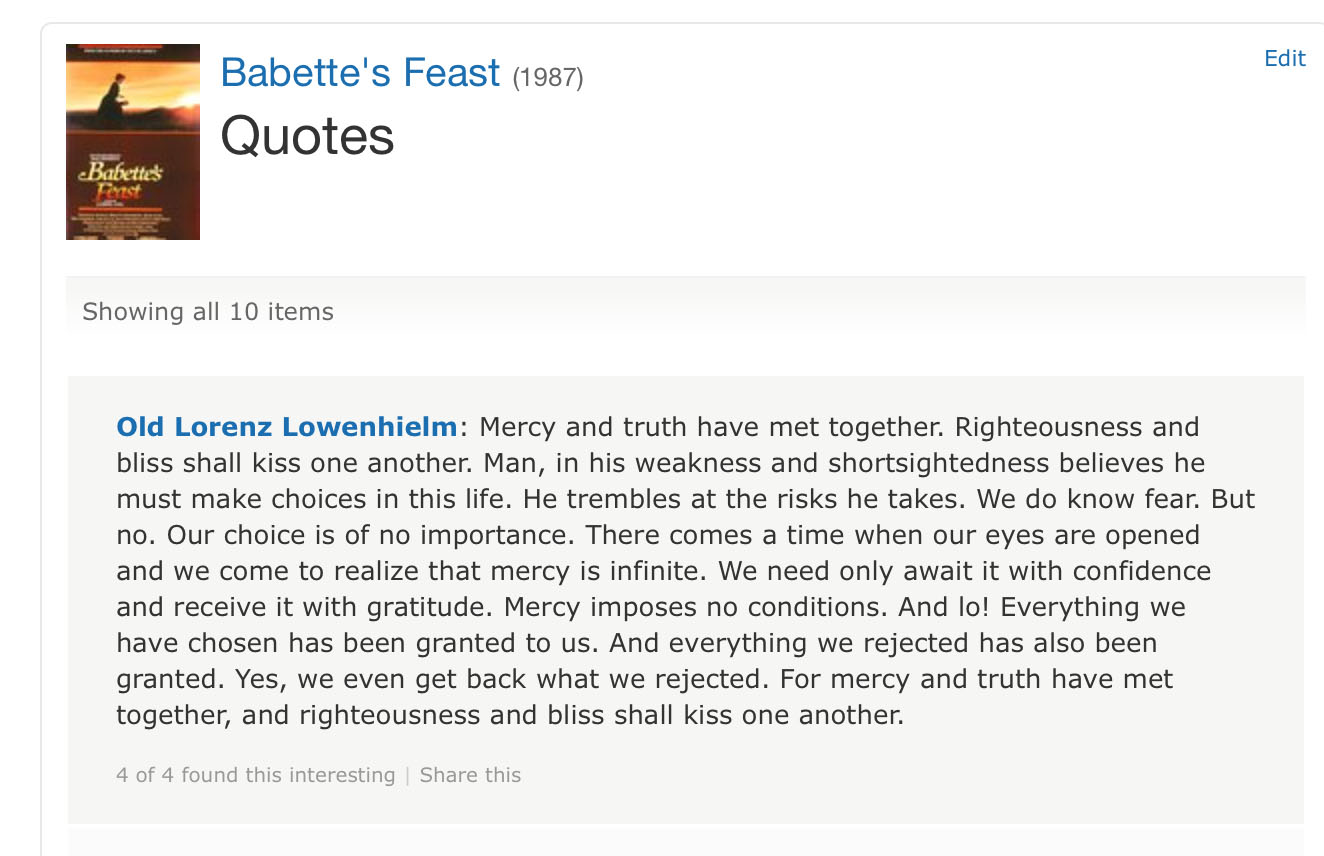

Choice is heavily emphasised in English dementia policy. Thinking about it more, choice is an inevitable consideration when the discussion becomes preoccupied that accounting phenomenon known as ‘scarce resources’. It is a political drive which can lead to rationing.

On the other hand, how much would you value ‘mercy’ and ‘compassion’ at? It is easy to know the cost of many things, and the value of nothing; and this is particularly so in residential dementia care I feel.

This quote for me summarises for me much of a shift towards a much healthier way of thinking for all of us:

A brilliant film.